17. Andrew

A NDREW County Durham, 11th May 1613

T HE MARE WAS BEGINNING to favour her near hind leg. Only a little, and had she been human I would have suspected she sought to disguise it, not wishing to show any weakness, for though she was soft she was stubborn.

It was hard work, carrying two people over such hills, and I'd hoped that our Sabbath at Alston would give her some rest. She had travelled well yesterday, and she'd been sound when we'd set forth this morning from Stanhope, but now she was showing this change in her gait.

I'd had hopes we'd reach Durham by evening, but I wouldn't ruin a good horse to do it. Besides, in the few hours since midday the clouds had been darkening over our heads, and the wind bore the scent of a coming storm.

Westaway, who had been riding at my side the past few miles, must have observed some change in my expression, for he said, ‘You needn't stop on my behalf. I am not tired.'

I smiled. ‘I see that ye are not. But that is gaining strength.' I nodded to the mass of deep grey clouds in the northeast. ‘We should seek shelter. Brancepeth Castle lies not far beyond those trees.'

‘And will its owner give us entry?'

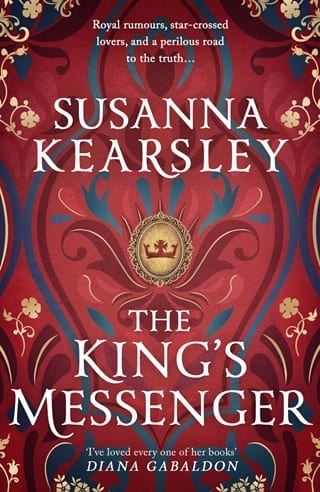

‘Aye,' I said. ‘Its owner is the king, and I am one of the king's Messengers.'

Westaway appeared confused. ‘But I thought you were trying to conceal that fact. For surely, Patrick Graeme—'

‘—has not been this way,' I finished for him. ‘Graeme has gone round another way, and seeks to cut us off, but that does mean he'll not have spread his lies here, and there's none who will be looking for a fugitive who's dressing as a Messenger.'

‘You hope.'

‘There's but one way to test my faith.' Dismounting, I undid the straps of my portmanteau and retrieved my scarlet livery.

Sir David drew the mare to a smooth halt a few feet distant. ‘What are you doing?'

‘What does it look like?' To Phoebe, I added, ‘Ye'll want to turn that way, and watch those hills. Aye, like that.'

Sir David said, ‘Yes, I see what you're doing, but why?'

‘There's a storm coming. Your cousin Patrick is still on the hunt for us. We need a place we can stop that is safe and defensible, and Brancepeth Castle is both. But they'll not be admitting us without the proper authority.' I'd only worn the blacksmith's father's jerkin for five days, but already it felt strange to take it off and don my scarlet doublet, and in truth I wasn't sure which suit of clothing felt more natural.

Hector asked, ‘Should I wear my red shirt, too?'

‘No,' I told him, then, seeing his face fall, I cushioned that with, ‘Best to wait first and see how we're welcomed.'

I'd not been to Brancepeth for years. The castle was well situated, flanked by wooded game parks where the bluebells were still making an impressive show beneath the trees. Its builders had wisely set it on the edge of a plateau, where the land fell away to the south and a broad stream – or beck, as they called it in this part of England – provided a natural moat on two sides, meaning no one could access it simply except through the village, which had been laid out in two straight rows of cottages facing each another like sentinels, all down the road to the castle.

Imposing behind its high stone wall and gate, Brancepeth Castle revealed little more than the tops of its staggered rectangular towers upon first approach, leaden roofs and pale stone blending well with the grey, inhospitable skies. At its back, the square tower of an old church rose from the trees as a rearguard.

The Graemes would not find it easy to come at us here.

First, though, we'd have to gain entry – a privilege the guard at the portcullis gate seemed reluctant to grant.

He was near to my own age, a half a head shorter, and rougher in manners and speech. I'd met countless versions of him in my lifetime, most often in taverns and alleys, all men long accustomed to being the biggest and strongest wherever they went, and in using that to their advantage. They didn't like having the tables turned, found it unsettling, and struck back however they could.

This guard, who apparently had the sense not to try striking me physically, launched an attack on my patience. He asked for my name, and the name of the town we'd just come from, and whether all five of us came from the court of King James – and, though I'd heard it said many times God hates a liar, I thought it would speed things along if I telt the guard aye, we all came from the court. And so that was my answer.

But when the guard drew himself up, high and mighty, and said, ‘I'll be seeing your warrant, then,' I wasn't having it.

Leaning in close to the portcullis bars, I tapped once, firmly, on the royal coat of arms embroidered on my chest in gold. ‘ This is my warrant, lad,' I told him. ‘When ye see that, ye open this gate, ye hear? Else ye will have the king to reckon with, and he's not such an even-tempered man as me.'

My sisters often told me when I spoke like that, when I went calm, I could be more intimidating than if I had raised my voice. I'd not have thought this guard could be intimidated, but he raised the gate.

He lowered his eyes, too, as we passed, but not before I'd seen in them a flash of fear. That, too, was unexpected. I'd allow my tone of voice and words might make the guard feel irritated. Apprehensive, even. But afraid? No. Something else lay at the back of that.

Nor was it confined to the guard. We came through the portcullis into a broad courtyard in the shape of a great octagon, with extra angles where the castle's southern towers faced us, shielded by the high stone curtain wall to one side and the lesser towers and stables on the other. And as one of the grooms came across to help us with the horses, I could see the same fear touch his features, too.

The groom looked quickly to the guard for reassurance, but the guard spoke sharply to him. ‘Give our guests assistance. See their horses are well stabled. I must go,' he said, ‘to fetch the constable.'

Westaway, at least, seemed pleased with our new situation. At the stable door, he eased himself down from the gelding's saddle with a sigh of satisfaction, looking round the spacious courtyard. ‘Well,' he said, and scanned the sky, ‘at least we will be safe here from the storm.'

I suspected we had stumbled unawares into a different sort of tempest, so I sent him a tight smile but said nothing, for I couldn't have in honesty agreed with him. And God does hate a liar.

Fullepub

Fullepub