Chapter 56: The Beginning

THE BEGINNING

“Maternity’s the other way!” the lady at the desk calls to Hannah as she passes through the front entrance and walks up the corridor towards the lift.

“Oh, I know,” she shouts back over her shoulder. “I’m not here for me, I’m visiting my husband.”

In the lift she stands, feeling the slow heave and shift of the baby inside her. Its movements have changed over the last week or so—not slowed down, as the midwives keep stressing. But instead of the frantic flurrying activity she has become used to, the movements are becoming more deliberate. Her child is growing into its limbs, and growing out of space to shift and turn. It’s flipped head down, the midwife said at their last appointment. I can’t promise it’ll stay like that, but… fingers crossed.

She puts her hand on the hard round bump jutting out just below her ribs. Its buttocks, the midwife had said, tracing the long rounded curve of her belly. And there’s its spine.

The lift pings and she heaves herself into action, out of the doors and up the corridor to the right, where Will’s ward is situated.

He is sitting up in bed, talking to a doctor, nodding.

Hannah hangs back for a moment, unsure whether to interrupt, but Will sees her and his face lights up.

“Han, come and sit down. Dr. James, this is my wife, Hannah.”

“Ah, so you’re the lucky woman,” the doctor says. “Fingers crossed we can have him up and about for the big day.” He nods at her stomach.

“Dr. James was just saying I could probably get a discharge tomorrow,” Will says, grinning.

“With conditions,” the doctor says firmly. “And sign-off from occupational therapy. Because obviously your wife isn’t going to be doing any lifting. You need to be able to maneuver yourself on and off the commode and so on.”

Will makes a face and nods, but Hannah can tell he’s taking it as read, and he puts out his hand and squeezes hers as hard as he can.

Afterwards, when the doctor has said his goodbyes and left, Will turns to her and pats the pillow beside him.

“Come on up.”

“Will, are you nuts?” Hannah looks at the narrow sliver of bed, and then down at her own ample width. “There is no way I’ll fit on there.”

“Come on.” He shifts himself across, wincing as he does. “You’ll fit. I’ll hold you in.”

Gingerly, trying not to disturb the dressing on his side, Hannah climbs up and slides into the narrow space beside Will on the bed. She leans back against his arm, feeling him grip her shoulder with a surprising strength. She remembers that long, nightmarish wait for the ambulance in the darkness of the beach, Will’s hand holding hers, slippery with his own blood, his grip faltering as he flickered in and out of consciousness, and her own heart stopping every time his grip slackened, imagining that this time, this time Will was slipping away from her, into the darkness, as Hugh had already done.

She shuts her eyes for a second, giving herself one long moment to acknowledge the horror of that night, and then opens them, firmly pushing the image away.

“Is that okay?” she asks, trying to keep her voice brisk and matter-of-fact. “I’m not hurting you?”

“You’re not hurting me,” he says. He brushes the hair off her face with his free hand, stroking her cheek with such tenderness that her heart clenches with love. “Now, tell me how it went this morning. Was it bad?”

“Oh, Will.” She puts her hand over her face. “It was awful. His poor parents. The vicar was amazing, but what could he say? How can you celebrate a life like that, knowing what everyone knows?”

“I’m still kind of amazed they let you all come,” Will says. “His parents, I mean. In their shoes… I don’t know. I think I would have said no mourners.”

Hannah nods slowly. She had been thinking the same thing in the limousine to the crematorium, wondering why Hugh’s parents had said it was okay, but when she felt Hugh’s mother’s arms come around her, she thought she understood.

“I know. Me too, but in a way…” She stops, looking out the window across the Edinburgh rooftops. “In a way, I think they knew we needed to say goodbye too… Do you know what I mean? Like, it was closure or something. And maybe…” She gropes for the words she’s seeking. “Maybe they needed to see me too. See that the baby and I were both okay, in spite of what he did.”

“Yeah, I get that,” Will says. He shifts, with a little grimace of pain, and Hannah tries to lean away from him, thinking she is hurting him, but then she realizes—he is reaching for his mobile. “Did you see,” he says as he slides it towards himself with his fingertips across the bedside locker, “the police made a statement about Neville?”

Hannah shakes her head.

“No, I’ve not been online much. What did they say?”

“Just… Hang on… let me find it.” He opens up his phone and begins scrolling down Twitter, awkwardly left-handed, because his right arm is holding her, then he stops. “Here it is.” He reads aloud from the linked article: “Thames Valley Police announced today that in light of compelling new evidence recently uncovered, they would be asking the Court of Appeal to begin the process of quashing the conviction of John Neville, sentenced in 2012 for the killing of Pelham College student April Clarke-Cliveden. Mr. Neville died in prison earlier this year, having protested his innocence to the end. His solicitor, Clive Merritt, commented, ‘It is a profound tragedy that John Neville did not live to see his exoneration, but died in prison for a crime which he did not commit. However, his friends and family will take comfort from the fact that his name will finally be cleared of this heinous crime.’ Geraint Williams, spokesperson for the Clarke-Cliveden family, said, ‘The Clarke-Clivedens extend their heartfelt sympathy to the Neville family over this grave miscarriage of justice. There is no joy, but some measure of relief, in the knowledge that justice will finally be done in this matter, allowing the friends and families of both April and Mr. Neville a peace they have been cruelly denied.’ A Thames Valley Police spokesperson expressed their profound regret and condolences to Mr. Neville’s friends and family. It is understood that no further persons are being sought in relation to the crime.”

They sit in silence for a moment, Hannah trying to come to terms with all of this. She imagines November, huddled in a cafe with Geraint, trying to put into words feelings for which there are no words, feelings which she herself has spent almost every waking hour since Hugh’s confession trying to figure out.

Because how do you come to terms with such a thing? How can Will live with such a betrayal by his best friend? And how can she live her life knowing that she condemned John Neville to a lonely, ignominious death?

“Hey.” She hears Will’s voice, feels his lips on her hair before she understands what is happening, realizes that there are tears running down her face. “Hey, Hannah, no. Listen to me. No more crying—do you understand? This wasn’t your fault. It wasn’t your fault.”

“It was,” she says. “It was, Will. I condemned him for being old, and weird and awkward—and that’s on me, don’t you understand? That will forever be on me.”

“It wasn’t your fault,” Will says, more urgently. “Hugh fooled you—but not just you, he fooled all of us. You, me, the police, the college authorities. Even April. Everyone. He was—” His voice cracks, and she remembers again his helpless crying in the days and weeks after the shooting. “He was my best friend, for Christ’s sake. I loved him. And I introduced him to you, to April. Doesn’t that make me just as culpable?”

Hannah lies back on Will’s pillows, and she takes a deep breath, trying to quell her own tears. She knows Will is right. This is on Hugh—and only Hugh. And yet, she is right too. They all believed Hugh not because of what he was, but because of what he seemed—charming, gentle, harmless, handsome. All the things that John Neville was not. And that is on them. And it will be, forever. She will have to learn to live with that knowledge—for the rest of her life.

“I tell you what ticks me off,” Will is saying now, bitterly. He wipes his eyes with an angry swipe of his free hand. “It’s that line evidence recently uncovered, like Thames Valley Police were the ones who dug all this up. Evidence handed to us on a fucking plate by a bunch of civilians at risk to their lives would be nearer the mark.”

Hannah nods. She and Will have talked about this—about that nightmarish night, about Will’s long, terrified motorbike journey through the darkness with Hannah’s voice whispering in his ear beneath his helmet as she drew Hugh inexorably through his confession. He has told her how it felt, that growing sick certainty as he sped around bend after bend, raced through tunnels, bumped over cattle grids, and he realized not just that Hannah was in trouble, but how and why.

It was his recording of that conversation that clinched everything with the police, and even now Hannah goes cold with a mixture of relief and fear when she thinks of that split-second choice, of what might have happened if Will hadn’t made the decision to record her call. She could have ended up in jail herself—or Will could have. Because when the police had finally arrived, to find Hannah hysterical, Hugh dead, and Will shot through the side and bleeding out into the sandy soil of the clifftop, they had been inclined to treat Hannah as the potential killer, cuffing her and bundling her into a separate ambulance as Will was blue-lighted away into the distance.

Her story, after all, was almost too fanciful to be believable—a decade-old murder, her own growing doubts, and Hugh’s actions—the kidnapping, the struggle, the shooting, first Will, and then himself, through the heart. Had his gun simply gone off as he and Will struggled back and forth with the barrel between them? Or maybe… Hannah thinks of his weariness in the car, the weight that seemed to be pressing down upon him as they drove deeper into the night. Maybe he had finally grown sick of the toll, of everything he had sacrificed to protect his own secret.

They will never know the truth about those final moments. Not even Will knows—the dark nightmarish struggle is as unclear to him as it is to Hannah, and all he remembers is his own pain, the shocking realization that he had been shot and was bleeding out, great gouts of spreading warmth. But it was Will’s phone in Hannah’s hand, sticky and red, the phone she had passed across to police, unlocked with shaking bloodied fingers, that spelled out everything else, Hugh backing up Hannah’s story in his own words. Bravo, Hannah Jones. So. You finally figured it out. I knew you would eventually.

But she hasn’t figured it out. Or not completely.

Because she still doesn’t know why he did it. No one does.

IN THE TAXI ON THEway back from the hospital she calls November on her new replacement phone, fills her in on the funeral, on how Will is doing.

“He might be out tomorrow,” she says, and just saying the words sets up a little thrill inside her—the thought of having Will back home. Battered and bruised, to be sure, with a hole in his side the size of a fist, and black and yellow hemorrhaging that’s spread across most of his torso, but home. It has been lonely these last couple of weeks, just her and the baby. Lonely, waking in the night gasping from nightmares that she is still there, still in that car driving to an unknown destination, with a man she knows to be a killer. Lonely, knowing that if something happens, if she goes into early labor or begins to bleed, it will be just her in the cab to the hospital, waiting for the doctors, trying to plead her case. The bruise where Hugh hit her has gone from blue-black to a sickly yellow-green, but she can still feel it sometimes in the night when she turns awkwardly, her whale-like belly dragging the blankets with her. It twinges, the torn muscles aching deep inside.

Her mother came up to stay for the first week, making her comfort food dinners like spaghetti and meatballs and big stodgy lasagnas. But after seven days, Hannah told her, gently, that she needed to go home. That she, Hannah, needed to get used to this, to managing by herself. And besides, she might need her mother here even more if Will wasn’t out before she gave birth.

“Come and stay with me,” her mother urged. “Just until Will’s well again.”

But Hannah shook her head. She couldn’t leave Edinburgh, not with Will so sick, not even in the early days when all she could do was sit by his bed and watch his eyes flickering restlessly beneath closed lids. Still less once he woke up enough to miss her presence.

“And how were Hugh’s parents?” November asks now, dragging her back to the present and Hugh’s funeral. “Was it weird?”

“Oh God, November, it was so weird. I just…” Her throat fills with tears at the memory of Hugh’s mother’s fragile bewilderment, his father’s stiff, brittle courage. “I had no idea what to say. He was their only child, their everything. What can you say?”

“And they didn’t… they didn’t throw any light on… why?” November asks.

“No,” Hannah says sadly. “I mean… I didn’t ask them. But they clearly loved him so much. I keep thinking about that last conversation I had with him at Pelham, before April died. When Hugh walked me back across the quad and talked about his father, and how proud he was of getting in to study medicine in his dad’s footsteps… it just… it kind of breaks my heart a little.”

“April always said he didn’t belong at Pelham,” November says. She sighs. “She told me once… how did she put it? Something about giving him a leg up, but it wouldn’t do him any good in the end if he couldn’t keep up.”

“Giving him a leg up?” Hannah is puzzled. “But April didn’t study medicine, how could she possibly have helped Hugh?”

“I don’t know,” November says. “I think a friend of hers helped people with their exams or something? Some kind of tutor maybe?”

Hannah’s breath seems to stick in her throat. April’s voice comes to her, as clearly as if she’s on the other end of the line, with November. Oh, that! I had an ex at Carne who made a pretty good living taking people’s BMAT for them.

And suddenly she knows.

It’s like the last few boxes of a sudoku, with almost every grid completed so that the remaining numbers simply slot in, as easily as one, two, three.

One. Hugh’s desperation to follow in his GP father’s footsteps.

Two. April’s leg up.

Three. The way Hugh had never quite felt up to the work at Pelham.

What was it Hugh had said? Chin up, and we’ll go easy on you in the exams. And Emily’s dry retort, just a few weeks ago but it feels like a lifetime now: Ain’t that the truth. There’s no way I deserved a first, and I’m pretty sure Hugh wouldn’t even have passed if it wasn’t for April.

So many small things made sense now. Hugh’s shocked horror that first night, at finding April in the dining hall. The way April ordered him around, made him fetch and carry, forced him to come to her play, even the night before his most important exam. Why did Hugh keep saying yes? Hannah had never understood that. But now it made sense. Hugh literally could not afford to say no.

And finally… the pills. The innocent little capsules on April’s bedside table, half-colored, half-clear. They had never figured out where April was getting those—it was before anyone knew about Silk Road and all the other darknet market sites. Back then, you had to know someone with access to a prescription pad. NoDoz for grown-ups, but not NoDoz at all. Stronger. Much stronger. Just as April had said to Hugh, that night at the theater. Sod flowers. You should have brought something stronger than that, Hugh… Just what the doctor ordered, am I right?

“Hannah?” November is saying now, on the other end of the phone. “Hannah? Are you still there?”

“Yes,” she says. Her throat is dry, and she swallows against the obstruction. “Yes, yes, I’m still here. I think I know. I think I know what happened. Hang on.” The taxi is pulling up to the mews, juddering over the cobbles, and she leans forward and pays the driver with her new, uncracked phone, and slides out to stand in the drizzling rain as the car drives off.

She feels a coldness sink over her as November says, “Hannah?”

“I’m still here,” Hannah says. The rain is running down the back of her neck. “November, I think I know why Hugh killed April.”

“Wait, what, you know? But just a second ago you were saying—”

“Yes, I know, but it was what you just said—about April giving him a leg up. She told me once, she told me that she had a friend, an ex-boyfriend, who took people’s BMATs for them.”

“What’s a BMAT?” November sounds more bewildered, rather than less.

“It’s the exam you have to take to get into Oxford to do medicine. It’s really important—Hugh told me once that if you do well in the BMAT, that basically overrides your interview, it probably even overrides your A-levels to an extent. And Hugh did well. He did really well. He got one of the highest marks in his year. It was what made me so puzzled, when he was so anxious about his prelims—because he’d aced the BMAT, so why was he worried about some crappy little first-year exam? Except maybe… maybe he didn’t ace the BMAT. Maybe someone else did.”

“But—but how could he do that?” November’s voice is shocked, uncomprehending. “April’s ex, I mean. How could he pretend to be Hugh? Or anyone, for that matter?”

“I don’t know,” Hannah says. She is desperately casting her mind back, trying to remember. “If it was like the entry test I took for English, it wasn’t like regular exams, you had to go to a testing center—and I don’t remember anyone asking for ID. I mean, why would they—what are the odds that someone roughly the right age and sex is going to turn up claiming to be Hugh Bland just to take an exam in his place?”

“Unless…” November says slowly, “unless you were someone who’d been paid to do exactly that. But how would Hugh have paid this guy? It doesn’t sound like he had much spare cash.”

“He didn’t,” Hannah says. “But he had a father who was a GP, and probably access to his prescription pad. It wasn’t digitized in those days—most GPs were still handwriting their prescriptions. How hard do you think it would be for a bright kid like Hugh to steal a few scripts and write them out for lucrative prescription-only drugs?”

“Drugs like dextroamphetamine,” November says, with a sudden, flat understanding. “Oh God. You even said it could have been a drug deal gone bad.”

“I think it was many drug deals gone bad,” Hannah says now. She feels an awful, desperate certainty. “April never did know when to stop, when she was pushing people too far. I remember her offering me the pills, the way she said there’s plenty more where those came from. I mean, she’d been taking them for ages, hadn’t she? Long before she came to Pelham. I think she must have been milking Hugh for drugs for months, ever since he took the test in fact. When she discovered he was at Pelham, she looked so pleased—like the cat that got the cream—and I couldn’t understand it, even at the time, because they were never particular friends. But I think this must have been why. Her little drug supplier—not just there in Oxford, but right at the same college as her. And she held it over him all year—until he finally snapped. But what could he do? He had no hold over April, she wasn’t the one who had taken the BMAT for him. She was just an innocent bystander. But April had a hold over him. And she was going to keep using it. Maybe forever.”

“But he didn’t say anything,” November whispers now. “He just told her sure, he could get her more drugs. And he probably even sympathized with her about you and Will, told her that she was quite right to be angry about Will fooling around.”

“He must have helped her plan that last prank,” Hannah says. “He probably suggested it, in fact. He must have convinced her to play dead, told her that he could persuade me there was no pulse, set me up to look an idiot in front of the Master and the rest of the college. And then, he leaned over her, pretending to be doing CPR…”

“And as soon as you left the room, he strangled her,” November finishes. Her voice is flat. There is a silence. Hannah stands in front of the door and feels as if a strange weight is both lifting from her and pressing her down.

Oh, Hugh.

“I have to go,” she says to November. Her voice cracks. “Will you be okay?”

“Yes, I’ll be okay,” November says sadly. “Bye, Hannah.”

They hang up.

Hannah puts her key in the lock and climbs the stairs to the flat slowly, step-by-step. She is out of breath by the time she gets to the top, her lungs made shallow by the child pressing up from beneath.

Inside she goes and sits in the kitchen, by the window, staring out into the street.

She should be phoning Will for the latest news on his discharge, contacting occupational therapy, booking taxis, arranging grab handles, setting all the thousand and one things up for his return home. But she doesn’t, even though she is longing for him with a force that is an almost physical ache inside her.

Instead she wakes her phone, goes to Google, and types something into the search bar—five words she hasn’t had the courage to search for in almost ten years. John Neville April Clarke-Cliveden.

And then she presses search.

The pictures flicker up, one by one, and each one gives her a little reflexive jolt, a shock of muscle memory from the time when every news item made her flinch, every headline was like a punch to the gut.

‘PELHAM STRANGLER’ CONVICTION TO BE QUASHED, SAYS THAMES POLICE

JOHN NEVILLE INNOCENT. HOW DID THE POLICE GET IT SO WRONG?

APRIL’S KILLER—JUSTICE AT LAST?

She clicks through to one at random, and there they are. Neville, glowering out of the page from his college ID picture, April in a photograph taken from her Instagram page, glancing flirtatiously over her shoulder in an emerald-green handkerchief dress.

Hannah looks at them both—and for the first time in ten years, she finds she can meet their eyes, even though her own are swimming with tears.

She reaches out and touches their faces—John’s, April’s—as though they can feel it through the glass, through ten years, through death.

“I’m sorry,” she whispers. “I’m so sorry, I let you both down.”

She doesn’t know how long she sits there, staring into their faces: April’s laughing, full of secrets; John’s dour and filled with resentment. But then her phone vibrates with the warning of a new email, and a little alert pops up. It’s from Geraint Williams. The subject line is How are you doing?

She clicks through.

Hi Hannah, Geraint here. Hope you’re doing okay, and the baby too. And I hope Will is feeling better. I spoke to November about your ordeal with Hugh; I’m so sorry, that sounds completely terrifying. I can’t believe what a nice bloke he seemed. I guess he fooled all of us.

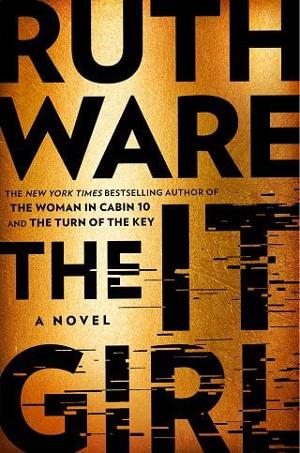

Listen, I thought twice about sending this, because I’m sure you’ve got enough on your plate with Will’s injury and the baby being due in a few weeks, and you may not be ready to talk (plus I’m not sure how much you can say until the police are finished doing their bit). But, well, I’m working on the podcast again. It’s a bit different from what I imagined, obviously. Neville’s innocence isn’t in dispute anymore, and most of the ten questions I posed in my original article are answered. So this one is going to be more about April and her life—and about the ripple effect of a crime like this. How the media treated her, her family, that kind of thing. I’m calling it THE IT GIRL. November’s agreed to act as executive producer and I’m pretty pleased with how it’s going. And what I wanted to say is, if you ever wanted to talk—put your side of the story. Well, I’d be honoured, that’s all. Your choice, and no hard feelings if you don’t or aren’t ready just yet.

I’m so glad we managed to get some kind of justice for Neville, in the end. He was obviously quite a troubled man, but he didn’t deserve that, no one does. I’ll always be grateful to you for making that happen.

Anyway, don’t answer straightaway. Take your time to think it over. But I’m here when you’re ready to talk—whether that’s six weeks, or six months, or even longer.

Geraint

P.S. The first episode isn’t finished yet, but if you want to hear a rough cut of the opening, here’s a link. Password is November.

Almost before she has had time to think better of it, Hannah clicks the link.

There is a short pause, and then a voice breaks the silence—not the one she was expecting, Geraint’s. Instead it’s a voice that’s eerily familiar, one that raises the hairs on her arms. It is high and reedy, in a way that once made her shiver just to imagine it. It is John Neville. But he doesn’t sound exactly like she remembers. He doesn’t sound belligerent and self-important. He sounds… sad.

“April Clarke-Cliveden was one of the most beautiful girls I’ve ever seen,” he says, the little sound bars rising and falling on her screen as he speaks. “They used to call her It Girl, because she had everything—looks, money, brains, I suppose, or she wouldn’t have been at Pelham. Everybody knew her, or knew about her. But someone took that all away from her. And I will never stop being angry about that. I want that someone to pay.”

Hannah reaches out and pushes the pause button on her phone, and for a long moment she just sits there, her hands pressed to her face, fighting tears. The baby turns inside her.

She thinks about Neville, about the truth, about how his voice has been silenced. She thinks about April. She thinks about the rest of her life, stretching out before her—a life that neither of them will ever have.

Her breathing steadies.

Then she crosses to her laptop and opens it up, bringing up Geraint’s email. She wants to reply before she can change her mind.

Dear Geraint,

Nice to hear from you. I saw your name in the news as the CC spokesperson. I’m glad November’s got you to support her with handling the press. As for me, I’m doing okay, thanks. So is Will—at least, he’s not out of hospital yet, but they say he may be discharged soon.

I know you said not to reply straightaway, but I’m going to—I’m going to give you my answer now, and please know that it’s not going to change.

I am ready. But not to talk. In some ways, I feel as if I’ve done nothing but talk. I’ve told my version again and again: to the police, to the courts, to you and November and Will. I’ve been telling it for more than ten years.

I’ve said everything. And now it’s time for me to shut up—and move on.

I listened to the opening of your podcast, and I hope it’s a huge hit. You know the truth, and you’ll tell it well. And April’s life deserves to be celebrated, just as Neville’s voice deserves to be heard.

But I’ve said enough. I’ve given enough of my life to April’s death.

Be safe. Stay well. Take care of November. She needs someone like you.

Love,

Hannah

She hovers for a moment, with her mouse over the paper airplane button, and then, very firmly, she presses it and the email whooshes away, leaving her staring at her inbox, and the line of folders ranked next to her unread emails. Bills. House. Personal. Receipts. And then finally, Requests.

Slowly, very slowly, she opens up the folder, and for the first time in years, maybe even the first time ever, she scans down the list of emails.

Hannah, urgent we talk! Fee available.

Message for Hannah Jones re Pelham Strangler case.

Important update on the Clarke-Cliveden case!!! Time sensitive!!!

ITV News request for comment re April update.

Interview request for Mail—please pass to Ms. Jones

There are dozens of them. Hundreds. Thousands, going back years, and years, and years. Slowly, very slowly, she checks the box marked “all.” A dialogue box pops up: All 50 messages on this page are selected. Select all 2,758 messages in Requests?

She clicks to select all 2,758. Then she moves over and presses the delete button.

This action will affect all 2,758 messages in Requests,her computer prompts. Are you sure that you want to continue?

She clicks okay.

The page hangs for a moment, as if giving her the chance to change her mind… and then the screen goes blank. There are no messages with this label it says.

Her email pings again, and she glances at it. It’s from a reporter she doesn’t know, someone called Paul Dylon. The subject line is Urgent request for comment re quashing of Neville conviction, for 6 o’clock news.

Hannah presses delete and watches as the message swirls away into the ether. She closes down her laptop, stands, and stretches long and hard, feeling the baby inside her shift luxuriantly, as if reveling in the extra space. The bones in her hips and spine click, and she releases a long breath.

Then she walks over to the cupboard in the corner of the living room, the one where they keep the screwdrivers and the Allen keys and the spare fuses. She pulls out the toolbox and takes it across to the window, clearing a wide space on the rug.

It’s time. She has a crib to build.

Fullepub

Fullepub