Chapter Four

August 21

It’s thirteen and a half hours to Oak Falls, and (despite the rental car starting to beep at me with an obnoxious message

on the dashboard that says, Do you want a break? ) I drive it all in one go.

It’s partly that I was wide awake at five this morning, so I figured why wait around? I might as well get on the road and

really beat the traffic.

Plus, once I was out of the city, I just wanted to keep going. Like if I got a little farther, I’d stop going over and over

everything Olivia said, everything I said, everything everyone else didn’t say.

And also, at a certain point, I kept going just to spite the rental car.

When I stopped for gas, I got coffee. When I got hungry, I bought a sandwich and ate it while driving.

And I kept checking my phone. Ian texted while I was following a semitruck through the rolling hills of Pennsylvania: Let us know when you get there. I got a Drive safe from Joan while I was stuck in the line for a tollbooth in Indiana.

I didn’t text back. I didn’t know what to say.

The third time my phone buzzed, I was at an oasis near Chicago—one of the rest stops that spans the freeway like a bridge

full of fast food. I fumbled my phone out of my pocket, hoping maybe this time the text would be from Olivia.

But it was my mom.

Got your bed all made up and ready for you. Make sure to look for penguins because I would like to know if you also think they are hideous.

It took me a minute to remember that she was talking about decorative penguins on sticks and not actual penguins who might

be roaming the suburban streets of my hometown.

The sun is going down and my back feels like someone kicked it by the time I exit the freeway and hit the county roads. The

speed limit is still fifty-five and there are two lanes in each direction, but there isn’t nearly as much traffic on these

roads. The big billboards are gone and the stuff I pass is everything that walks that line between suburban and rural: a sprawling

clinic with an ER and a parking lot that probably fits a hundred cars, a big chain grocery store, a massive lumberyard. Compared

to New York, everything is weirdly huge here. Islands of civilization in the middle of a whole lot of cornfields.

The cheerful Google Maps lady is telling me what turns to take, but once I cross into Oak Falls, I switch her off. I know

all of this by heart, even in the gathering twilight and even after all this time.

Oak Falls doesn’t have some super cute sign with a super cute catchphrase to tell you when you’ve officially arrived. Probably

because Oak Falls isn’t a tourist town and never aspired to be one. There’s no pristine lake or massive forest or anything

else to draw people here. So the only sign is a plain white affair with plain black letters: oak falls, pop. 8,073.

There’s a back-roads route I could take to my mom’s house—or... a more back-roads route, since everything is practically a back road in Oak Falls. It’s the route I took when I’d come home from

college, because I was so done with Oak Falls that I didn’t want to see any more of it than was absolutely necessary.

But now, I turn the hatchback toward Main Street. The streetlights are on when I get there, casting pools of yellow light

over the pavement and the sidewalks. They’re small streetlights—not even as tall as the two-story buildings around them, black

poles with lights on top shaped like globes. The streetlights in New York are at least twice that height, skinny and silver

and utilitarian, blending into the urban landscape around them.

I slow down, creeping along at ten miles an hour. It’s not like there’s anyone behind me to get annoyed.

The buildings lining Main Street are mostly made of red brick, all attached to one another in a row. It’s picturesque in a

way that screams Middle America—or at least “stock image for one of those Ten Best Places to Live When Chicago Is Too Expensive”

listicles. Most of the storefronts are dark, and I don’t really look too closely at any of them. Just scanning, looking for...

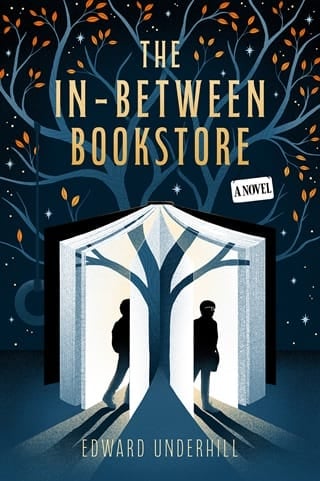

In Between Books.

I pull the car over to the curb, into an empty space right in front of the store. Turn the key and the engine sputters to

silence.

The store is closed. It’s almost eight thirty. The plastic sign hanging in the door says, will return 10:00 , and some of the lights are off. But now that I’m here, I have to look. I have to at least peek in the window.

I open the car door. For once, it’s a good thing I’m so short, because I have a feeling I’d be even more sore if I was actually

the height of an average guy. I glance up and down the street, but I don’t see anyone coming, so I stand with my back to the

car and rub my butt in an effort to get the blood flowing again.

My legs are stiff as I go up to the store. It looks like most of the other storefronts along Main Street—a big square window

in a brick wall next to an old wooden door with panes of glass in its top half. The letters on the store window look new:

in between books is arched across the window in white frosted letters, instead of the peeling vinyl stickers that I remember.

I lean forward, peering through the glass. The front table display is exactly where it’s always been, stacked with the newest

releases. Beyond, I can see rows and rows of shelves. Even the clock on the wall above the door to the back room is the same—made

out of an old copy of a Sherlock Holmes novel, with gold numbers stuck to its burgundy cover and hands that look like fountain

pens.

All the way at one end of the store is the cash register, under a hand-painted sign that says, checkout .

There’s someone behind the counter—in the process of closing up, I guess. A kid in an oversize hoodie, with short, scruffy

hair, a pale face, and wire-frame glasses...

My heart suddenly thuds, and my stomach feels like it’s fallen down ten stories.

I wore oversize hoodies all the time in high school.

I had wire-frame glasses.

I must have closed up the store dozens of times, and I always turned half the lights off, just like this, even when I was

still working, because it was weirdly cozy to be alone in a half-dark space with all those books...

This kid, the dimness of the store, the books stacked on the display table—it all reminds me so much of back then that for a second, I can smell the faint mustiness of the books. I can hear the tick-tick of the clock above the door to the storage room. I can feel the slight greasiness of the cash register keys under my fingers.

The way the cash drawer constantly stuck halfway when you tried to close it. I remember exactly how muted the colors of book

covers became when I’d unpack boxes of books in that half-light of closing time. The way the stool I sat on behind the counter

had one leg that was shorter than the other three, and it always tilted precariously. The way the edges of the bookshelves

cut awkwardly into my back when I sat in the aisles with Michael, reading books for hours...

I squeeze my eyes shut and turn around, rubbing my eyes under my glasses. My bigger, plastic, tortoiseshell, modern glasses because I’m not in that bookstore anymore. I’m not sixteen anymore.

But for a moment, I could swear I was. I could swear I was right back there, and it all felt real.

Good job, Darby. This is what being on the road for almost fourteen hours straight will do to you. You arrive in your old hometown and you’re

exhausted and all caught up in weird nostalgia feelings, and you see some random teenager who kind of looks like you and you

flip out.

What am I doing here?

I should go to my mom’s house. Quit lurking outside this bookstore like a total creep. The store’s closed. I can come have

nostalgia feelings about it tomorrow.

I turn for the car—and bump right into someone.

It’s not a very hard bump at least, but I definitely stepped on a foot that was not mine and mashed my glasses.

Whoever the person is says in a low voice, “Ope, sorry—I didn’t mean...”

“No, my fault.” I jump back and look up and... “Oh, shit.”

The guy in front of me raises his eyebrows. He’s taller than me, but not really tall —maybe five-foot-nine. He’s wearing a checkered short-sleeve button-down and dark, nice jeans. His auburn hair is cut classic

and neat, but it’s also vaguely curly in a way that makes it look a little rumpled, like he’s been running a hand through

it all day and hasn’t bothered looking in a mirror. His nose is still slightly big, but it looks like it belongs now, and

even though it’s getting dark outside, I know his deep-set eyes are actually, really, honest-to-god gray, just like I know

he used to wear glasses and he once had a whole collection of Pokémon T-shirts...

Because the guy standing in front of me—the guy I just walked right into like a fool—is Michael Weaver.

“Sorry?” he says.

Oh god . He has no idea who I am. Of course he doesn’t. I’ve been on T for ten years. I’m almost sinewy (if you don’t look too closely),

my face shape is different, my voice is different. I look like the older brother of the person he knew. The person with different

clothes, different pronouns...

Different everything.

“No, I’m... I’m sorry.” I take a step backward. “Wasn’t watching where I was going. I should, uh... I should go.”

He’s staring at me. I see the moment everything suddenly clicks into place. And then he says, “Darby?”

Well, fuck. I was ready to turn tail and run. Because the thought of trying to explain was way too overwhelming. And anyway,

this is the guy who decided to ignore me our last semester of high school.

I try to force a grin. It feels like a grimace. “Yeah. Uh. Hi.”

“You’re...” He’s fumbling. “Um...”

“Trans?”

“Here.”

My face heats up. My pulse is racing. I take an awkwardly large gulp of air, trying to slow down my heart. “Yeah. I, um...

My mom is moving. I came to help her pack up.” I nod, like somehow this is going to provide more emphasis.

“Oh.” He’s still staring at me, but I can’t read the expression on his face. It’s like he’s seeing me and not seeing me at

all. “Right. I think I heard that from Jeannie Young.”

“Jeannie Young?”

“Yeah.” He hesitates. “You know, with the penguins.” Now he looks flustered. “Or... I think it was flamingos when you were here—”

“Yeah, no, I know Jeannie Young.” I can’t tell him that my real question was why on earth he was talking to Jeannie Young.

Does he just do that now? Talk to all the adults who have been here, the whole time we were growing up, because he still lives

in this same small town and sees them at the grocery store?

“I’m... sorry.” Michael rubs the back of his neck, which makes me notice his arms, and how much less lanky he is than the

last time I saw him. He’s not gawky anymore. He’s actually sinewy. “Is it... or, I mean... do we need to be reintroduced?”

I blink and make myself stop staring at his arms. “What?”

His forehead wrinkles. He looks like he’s in physical pain. “I called you by the name that I knew and then I realized maybe

you...” He waves a hand, a little desperately.

“Oh.” He’s worried he just deadnamed me. “It’s still Darby.”

His shoulders lower. “Right.”

“I just, um... I kept it. You know, because it was technically after my uncle and stuff, even before, so—”

“Yeah, I remember.” I think I see a smile cross his face. The same slightly crooked smile he had in high school. It’s so familiar

that for that second, he looks exactly the same as the gawky guy I once knew, even with his neater hair and without his glasses.

And then the smile is gone. “I should, uh...” He waves a finger vaguely in the direction he was going.

“Oh. Yeah.” I step out of his way.

“Nice to see you.” But he’s not even looking at me.

“Yeah. You too.” I turn and head back to my rental car. Just to make clear that I’m going someplace too. That I have someplace

to go.

I get back in the car, but I still have an excellent view through the windshield of Michael Weaver walking down the sidewalk,

leaving me behind.

My mom wasn’t kidding about the penguins.

Jeannie Young has always lived in the beige single-story ranch next to my mom’s split-level, but even if I’d somehow forgotten this fact, it would have been obvious which house was hers. There’s a literal penguin flag flying next to the front door. There are also plastic penguins on stakes in the yard (at least ten), a birdbath (held up by a penguin pedestal), two very realistic and presumably life-size penguin statues on either side of the walkway, and a collection of stone baby penguins lining the front steps.

The front door of my mom’s house flies open as soon as I pull into the driveway and out shoots my mother, in polka-dot pajama

pants, a bathrobe, and Crocs, arms outstretched, barreling at top speed toward the car.

I manage to get out just before she plows into me, wrapping me in a hug. My mother is one of the few people I know who is

noticeably shorter than me—she’s pretty much the definition of petite, with a graying pixie cut and bright-red round glasses.

“Darby! You’re home!” She lets me go and stares deeply into my eyes. “Aren’t they ugly?”

“What?”

“The penguins.” She turns and glowers at the yard next door, hands on her hips. “Isn’t it just the tackiest, most horrid thing

you’ve ever seen? You know, I’m worried they’re going to lower my property value.”

“Mom!” I glance around. “Jeannie could hear you.”

She just snorts. “Jeannie barely hears anything anymore. I keep telling her she needs hearing aids but she won’t listen. Probably

because she doesn’t want to hear what anyone thinks of her penguins!” Mom turns her attention to the hatchback rental car.

“You fit everything in that ?”

“My apartment was small.” It comes out a little defensive. “And I sold most of my stuff.”

She looks at me—a long, shrewd look. “I see. Well.” She soldiers past me and opens the trunk. “Let’s get what you need for

right now and we can worry about the rest tomorrow.”

I feel uncomfortably like I’ve just come home from college on a break. “Mom, you don’t need to carry my stuff.”

“Oh, don’t be silly. I can handle a suitcase. Load me up.”

I do not, of course, load my mother up. I give her one suitcase with rolling wheels. And then I grab my messenger bag, my

pillow, and a trash bag I’m pretty sure has clothes in it, and close the trunk. Beep it locked. Not that anyone probably steals

anything around here. It’s Safe. As my mom kept saying whenever she came to visit me in New York.

“Did you hit any of that construction on Thirty-Six?” Mom heaves the suitcase across the threshold into the house. “I swear, they just keep digging the road up and then sitting around and not doing anything. It’s a highway, not a sandbox!” She sets the suitcase down and shouts, “Mr. Grumpy!” Turning to me again—“He’s getting a bit deaf these days.”

I hear the click-click of dog nails, and Mr. Grumpy rounds the corner from the kitchen into the living room. His long ears are practically dragging

on the floor, and he’s wheezing, but his tail wags when he sees me.

I drop the bags and squat down. “Hey, Grumpypants.”

He waddles into my outstretched hand, butting his head against it, tongue lolling out of his mouth.

“You want some water? A snack? I just made a frozen pizza for dinner myself, because I need to get to the grocery store, but

we’ve got crackers, apples, some cheese...” Mom disappears into the kitchen, leaving me alone with Mr. Grumpy, looking

around the house where I grew up.

It looks... the same. Same off-white wall-to-wall carpeting, though Mom has tried to hide it with a big blue-and-white-striped

rug that’s new. She’s still got the same light-brown sofa and armchair set, the same honey-wood coffee table, the same bookshelf.

Even the books on the bookshelf are familiar—a mix of classics like Pride and Prejudice, The Three Musketeers, poems by Emily Dickinson, and volumes of Shakespeare, and kids’ books that went in and out of her classroom when she was teaching

fourth and fifth grade. A Wrinkle in Time . The Witch of Blackbird Pond. The Phantom Tollbooth. Some more I don’t recognize—books she must have acquired after I left for college.

There’s a TV on a table against the wall. That’s new. When I was growing up, Mom relegated the TV to the basement.

“So?” Mom pokes her head around the wall separating the living room from the kitchen.

I jerk, pulling myself out of memories of watching episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer with Michael. We’d rent the DVDs from the video store on Main Street, make a bag of microwave popcorn, and sit in the basement

on an old futon. We watched the whole series that way.

“Sorry,” I say. “What?”

“Snack?” Mom says.

“No, I’m okay.” I didn’t stop for dinner, but I can’t tell if I’m hungry or not. I’m too unsettled.

“All right.” Mom stands awkwardly in the doorway between the living room and the kitchen, arms folded, fingers tapping idly.

“Well, would you like to watch Marble Arch Murders with me?”

That snaps me out of my thoughts. “What’s that?”

“An English show on PBS every week at nine. They do great murder mysteries over there, you know. It’s about an old lady solving

crime in London. It’s nice to see someone my age on TV.”

“Since when do you watch TV?”

She looks a little offended. “I always watched TV. Don’t you remember watching Frasier with me?”

Well, yeah. That last semester of high school. When I had no friends and nothing else to do, and Mom decided that TV wasn’t

so bad after all, at least not if both of us were watching it in the basement and it was reruns of Frasier .

“Yeah, I just... didn’t realize you watched anything else.”

She sniffs. “I watch the news and murder mysteries. I have cable now. It’s too expensive. I should get rid of it. But I like

Rachel Maddow.” She switches on the TV and sits down on one side of the couch. Mr. Grumpy immediately puts his front paws

up on the cushions and she reaches down, wrapping her hands around his butt, and hauls him up next to her. “Come sit with

us!” She points at the remaining couch cushion on the other side of Mr. Grumpy.

I glance at the TV, playing an upbeat credits sequence featuring an old lady in a purple wool coat traipsing through the streets

of London and looking suspiciously at things. “That’s okay. I’m just gonna take my stuff to my room. Maybe take a shower or

something.”

“Okay.” My mom shrugs and then gives me a big smile. “Good to have you home, sweetheart.”

I manage to smile back at her. But it feels stiff. Like I’m rusty. “Yeah. Thanks.”

She settles in with her show, absently stroking Mr. Grumpy’s head, so I pick up my bags and wheel the suitcase down the carpeted

hallway. Up the few steps and then around the corner into my childhood bedroom.

Just like the living room, it also hasn’t really changed. I guess I don’t know what I expected. Did I think my mom would turn it into a crafting room or a yoga studio or something?

But my room looks the same as I left it. Guilt washes over me. I haven’t been back here for years, but Mom’s still got the

pastel-striped comforter on my twin bed. The light-blue carpeting has faded a little with age, but the off-white walls are

still covered with pictures of wolves that I cut out of the free calendars my mom used to get in the mail. The pages from

magazines of random celebrities and bands I thought I was supposed to care about are still there too, along with a grainy

rendition of the Mona Lisa , printed on regular printer paper, because I guess I thought I needed some real art.

There are some gaps on the walls. Gaps where I’m pretty sure there used to be photos from high school. I took down every picture

with Michael in it after I got back from boarding school, when it was really apparent our friendship was over. I took down

everything else the first time I came home from college. I walked into my room with a proper guy’s haircut, wearing a binder,

and immediately got rid of anything that was a reminder of the old me. The girl me.

I ditch the suitcase and the trash bag of clothes and wander over to my dresser, pulling open the drawers. Except for a random

jewelry box and a container of hair ties, they’re empty. Like my mom expected me to come back and need them again.

I sit down on my bed, rubbing my stiff knees, and glance out the window. It’s dark outside now. Too dark to really see anything

except my own face reflected back at me.

God, that kid—the one behind the counter of In Between Books... that kid really looked like me. Reminded me of me.

But that’s all it was... just a kid who reminded me of myself, who looks kind of like I used to look. Whatever kid works

there now when they have summers off from high school. Whatever kid closes up the store, locking up the register. I guess

that kid likes working in a weird half-light too.

What was Michael doing, walking down Main Street past the bookstore on a Sunday night? What does he do in this town where we grew up, and where he just... lives now?

What did he think, seeing me after all this time?

I rub my eyes again. I should go out and watch TV with my mom. It’d be a distraction. Maybe old ladies solving murder mysteries would be fun.

But it felt weird to see my mom doing what she clearly does every week. Just her and Mr. Grumpy. Carrying on with their lives

when I haven’t called or talked to her in months.

It’s weird to see all the things that happen that I don’t even think about. To see the things that have changed when I’m also

surrounded by all the things that haven’t.

So I don’t go out to the living room. I pick up my phone and open the group chat. I should text my friends. I told them I

would. They’re my friends.

But everything I yelled and everything Olivia yelled is still too close. Too loud. I can’t tell them how weird I feel, sitting

here. It’ll just be proof they were right—this was a terrible idea.

In the end, I just fire off a quick Got here . And then I heave myself off the bed and head for the shower, trying to tell myself this is fine.

Fullepub

Fullepub