Chapter Two

August 12

Living on the top floor of a five-story walk-up has its perks. Or... perk. It’s marginally less expensive than living on

the fifth floor of a building with an elevator.

This is not super easy to remember as I drag myself up five flights of stairs with a pounding headache. It took me more than

an hour to get home from the Lower East Side, thanks to Friday-night construction on the subway that meant I waited twenty

minutes for a train. Then the train was freezing, but it was still sticky and hot outside the moment I got off, and that,

plus the combination of alcohol and sexy fries, has me ready to barf. Why did I think I could drink two whole glasses of beer?

I manage to unlock my door and for once I’m thankful that my apartment rings in at a grand total of two hundred and fifty

square feet, because once I drop my bag, it only takes me seven steps to cross the whole place and face-plant in my bed.

Ugh.

For a blissful minute, I just lie there, pretending nothing else exists. Just me and my old IKEA bed that’s definitely sagging

in the middle. Whatever. It’s comfortable.

But I can’t actually stay here, because my air conditioner is too far away for me to reach, and my apartment feels like an

oven, even at ten o’clock at night.

So I push myself up and off the bed and stagger over to the AC unit stuffed into the single window at one end of my apartment, cranking it to high. Ditch my shoes. Peel off my shirt and throw it at the laundry hamper stuffed into the corner. The same laundry hamper I’ve had since college. It’s short and wide—exactly the wrong shape for New York City. In New York City, everything is narrow but tall, including apartments. My studio might be only two hundred and fifty square feet, but it’s got ten-foot ceilings. The Craigslist ad listed this like it was a big selling point: Soaring ceilings give spacious and airy feel.

Honestly, when I moved in here, I thought the tall ceiling was a big selling point too. I was right out of college, starting

my master’s program, and yeah, this apartment was tiny and a fifty-minute subway ride to NYU, but it was mine . It was the beginning of a new life. Just like New York City was the beginning of a new life when I got to college. The very

definition of possibility . Here, finally, I could be myself—all parts of myself—and get lost in the noise and the crowd and the sense that everyone

around me was doing something.

But now...

Now it’s like the noise gets louder every day, and my apartment just gets smaller. I mean, my kitchen is barely even a kitchen.

It looks like the adult version of one of those kitchen play sets you get as a kid—the kind where the sink, microwave, and

oven are all sort of attached into one thing, maybe with a tiny strip of counter and a single cabinet, if you’re lucky.

I drink a glass of water, which makes me feel slightly less gross, and rub my temples, looking down at my messenger bag sitting

on the floor. I could leave it for tomorrow. I could collapse on my bed and ignore everything until the morning.

But somehow, I’m quite sure that if I leave it, full of everything I brought home from the RoadNet office, I’ll just feel

worse unpacking it tomorrow.

So out comes my NYU mug, which I only brought because everyone else at RoadNet had mugs that said stanford or harvard or columbia . Out come all my notebooks. My folders of random handouts from random meetings. Fancy graphs promising profits that clearly

never showed up. Where am I going to put all this stuff? I don’t feel like I can just ditch it. Some of it I should probably

shred.

And who knows when I’ll find a shredder now, so... under the bed it is.

I put my bed up on riser blocks when I moved in here because that’s the real secret to existing in NYC-size apartments: hiding stuff under your bed. Put your bed up on risers and you can hide even more stuff.

And honestly, hiding stuff—in this case, all the evidence of my latest fail—sounds great right now.

I reach under my bed and pull out the first cardboard box I find. Every box under here is a leftover moving box. I kept hanging

on to them, just in case. Which I guess was smart after all, since unless I magically get a great-paying job in the next three

weeks, my thirtieth birthday will be spent moving.

I open the box flaps and stuff in the notebooks and folders, pressing it all down on top of a winter jacket and a few random

books.

Halfway through shoving the box back under the bed, I notice the fading black text on the side.

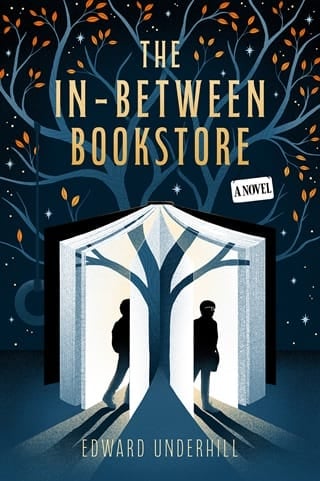

In Between Books

Oak Falls, IL

My heart does a funny little skip. In Between Books. The independent bookstore I worked at the summer after junior year of

high school, the summer after senior year, and plenty of weekends in between. It was Oak Falls’s only bookstore, owned by

this weird old guy named Hank, who wore yellow-tinted glasses and probably only hired me because I was hanging around so much

anyway. In Between Books was one of the places Michael would ride his bike to, with me balancing on the back. We’d spend hours

just lurking in the bookstore, sitting on the floor between the shelves and paging through stuff like it was a library.

Probably super annoying, actually, but Hank never seemed bothered.

I pull out my phone, pull up Google, type Michael Weaver...

But I don’t hit search. Just like I haven’t hit search in years.

Because why would I want to search for the guy who used to be my best friend until my seventeenth birthday party? The guy

who decided, once I got back from my semester in upstate New York, that he’d moved on and didn’t care about me anymore?

That last semester, senior year of high school, it was just me and In Between Books. Me sitting behind the counter in my oversize clothes, with my short hair, picking up any extra shift Hank wanted to give me because I didn’t have anything else to do. Reading whenever there weren’t any customers around—which was a lot of the time—because at least getting lost in a story about somebody else was a distraction from all the ways I felt out of place and alone.

A person everyone else saw as a girl, who knew, even back then, that girl felt all kinds of wrong.

I didn’t do anything about it until I got to college. Until I met Olivia, and then Ian, and suddenly the idea of buying a

binder, of coming out, of going to the LGBT center in Manhattan and actually transitioning ... none of it seemed so insurmountable, so paralyzing, anymore.

I tap the backspace key. Erase Michael Weaver from the search bar. Push myself to my feet, toss my phone onto the bed, and

pull an old stretched-out T-shirt over my head.

I forgot that I stole boxes from the back room of In Between Books. The last summer I worked there, I’d sneak one out with

me after every shift and use them to pack for college. And then, at the end of that summer, I packed all those boxes into

the back of the absolute beater of a station wagon my mom had gotten me for graduation, and I drove to NYU.

I’ve been back to Oak Falls, to my mom’s house. I went home for some breaks in college. But then the beater station wagon

died, and plane tickets were expensive, so I called my mom on the phone instead. She never complained.

And then one summer I got an internship at a newspaper. And the next summer I worked at a magazine. And then I was going to

grad school, focusing on those dreams of teaching, working in publishing, maybe writing something myself, and then...

I don’t even remember all the and thens . But I never went back to In Between Books, even when I visited my mom those few times in college. It felt like a piece of

a previous life, and I was trying very hard to live in my new life.

My mom visited me occasionally in New York. But she wanted to do all the touristy things, and I was completely mortified,

because people who live in New York never do the touristy things. So eventually, we stopped doing that too. And now...

I pull out my phone again. This time, when I pull up Google search, I type In Between Books .

In Between Books

33 Main Street

Oak Falls, IL

According to Google, it’s still there.

I go to the list of contacts in my phone and, before I can second-guess myself, tap on Mom .

Three rings. And then she answers: “Is this Darby’s butt?”

This was not the answer I was expecting. “Mom?”

A second of silence. “Oh! Darby!”

“Did you just ask about my butt?”

“I thought you butt-dialed me!” She sounds defensive, like this is a perfectly reasonable excuse.

I can’t figure out whether to laugh or be vaguely offended. “Mom. That’s not a thing. Nobody butt-dials anyone anymore.”

“Oh, that’s definitely not true. Just the other day I was talking to Jeannie Young—you remember Jeannie Young? You knocked

over one of her flamingos when you were learning to drive. Anyway, Jeannie told me just the other day that she butt-dialed

her grandson by mistake.”

This is far too much information for my brain to take in through the booze and the headache. “Who has flamingos?”

“Jeannie Young. You remember Jeannie! You used to sell her sexless cookies.”

“Oh, god.” My face turns into a furnace. I was in Girl Scouts for a couple years as a kid, until my mom decided it was too

far to drive to the closest troop. When I came out, I asked her to use he and him even when she talked about me as a kid, and she took this so seriously that she refuses to reference any girl things in my

past. But she also hasn’t absorbed the term gender neutral, which means Girl Scout cookies have become sexless cookies .

At least when she talks to me. I really hope she doesn’t refer to them this way to anyone else.

“Jeannie finally got rid of that hideous flamingo herd, by the way,” my mom says. “We had a few months of peace and then you’ll never guess what she replaced them with.”

I rub my forehead. “What?”

“Penguins!” My mom sounds incensed. “She’s got these incredibly tacky penguins on spikes in her yard now. She even put up

an inflatable penguin with a Santa hat last Christmas. I don’t know where she gets these things. It’s not like the garden

center has such ugly stuff.” She sighs. “Anyway. So you didn’t butt-dial me. What’s wrong?”

“Why do you think something’s wrong?”

“Because you never call me, Darby.”

She doesn’t say it with any malice. Or even like she’s trying to guilt-trip me. It’s just a casual observation.

But I feel guilty anyway. Because it’s true. I haven’t called her for...

Well, I can’t actually remember the last time I called her. Which isn’t a good sign.

“Sorry, Mom. I guess I’ve been—”

“Busy.” She says it lightly, but it makes me feel worse—because it’s exactly what I was going to say. “It’s all right. What’s

that god-awful noise?”

“Oh, crap. Sorry.” The AC is still roaring away, cranked to its highest setting. I must sound like I’m inside a cement mixer.

“One sec...” I flip the dial and the unit quiets with a shudder. We’re suddenly left with silence. Or as close to silence

as you ever get in New York City. There’s a siren going somewhere outside, and another train pulls into the subway station

a block away with brakes shrieking.

“Well,” Mom says. “If everything’s all right, maybe we could chat tomorrow? It’s getting a bit late now. Mr. Grumpy and I

were just about to go to bed.”

“Oh. Right.” It’s an hour earlier where she is, but my mom has always been an early-to-bed-early-to-rise type. Probably all

the years of being a teacher. “Sorry, I wasn’t even paying attention...”

“That’s all right.” A pause. And then she says, a little tentatively, “You sure you’re okay, Darby?”

Yeah.

Fine.

It’s what I’ve always said before. The only exception was when I finally came out to my mom. Sometimes, I feel like we’re still recovering. Like we used up everything we had on that conversation, and now anything beyond canned responses is just overwhelming.

But this time, before I can think better of it, I say, “The company I worked for is folding, so I’m out of a job. And my rent

is going up. And I’m just sick and tired of New York, or maybe I’m sick and tired of myself, and this isn’t really where I

thought I’d be when I turned thirty.”

It rushes out, absolute word vomit. I try to add a laugh, just to sound at least a little fine, but it comes out panicked, a good octave higher than usual.

“I’m sorry, sweetheart,” my mom says quietly. I hear a weird little grunt in the background, and she adds, “Mr. Grumpy says

he’s sorry too.”

That makes me laugh for real, at least for a moment. Mr. Grumpy is the truly ancient basset hound my mom still has. We got

him when he was a puppy. He must be going on fifteen now. She sends me pictures of him sometimes—the black and brown has faded

to gray on his face and he looks saggier than ever.

He’s not really grumpy. He just always had sort of a resting grump face. It’s probably all the forehead wrinkles.

“What are you going to do?” Mom asks.

Isn’t that the million-dollar question. “I don’t know.”

“You know, I was going to call you.” She sounds tentative again, which doesn’t fit her. My mom is not generally a tentative

person. “But since I’ve got you now... I’ve got some news too.”

The first thing that crosses my mind is that Mr. Grumpy has some fatal cancer. He’s sick. He’s got weeks left and for some

reason she’s only telling me now...

“I’m downsizing.”

My brain screeches to a stop. “What?”

“I’ve decided to sell the house. It’s more house than I need, really, and I’m by myself and getting older. And they just built

these new condos right off Main Street, near the park. They’ve got elevators, and they allow dogs, so I went to see one and

it was very nice, so...” She clears her throat. “So I decided to buy it.”

I can’t seem to take this in. “You bought a condo?”

“Don’t sound so shocked! I’ve been thinking about downsizing for a while. And this way I won’t have to look at Jeannie Young’s

penguins anymore.”

Well, at least she knows what her priorities are. “Sorry, I just... you never told me.”

“Oh, I didn’t need to bother you with all this.”

I’m not sure how to feel about that. It’s weird to think about my mom making decisions about the place I grew up without me.

But then again... why should she need to get my permission? It’s her house.

And I left.

“You can bother me,” I say, but it sounds hollow, even to me.

“I was going to tell you,” she says. “Because I’m going to have to get rid of a whole bunch of your stuff to fit in the condo.”

“What stuff?”

“Stuff! Books, school papers, stuffed animals... your bedroom still has plenty of stuff in it, you know. And then there’s

the basement. There are skis down there! I don’t even remember when we went skiing. Did we go skiing?”

I have absolutely no memory of ever going skiing. “Mom,” I say, “do you remember In Between Books?”

She pauses. “What about it?”

“Is it still there?”

“Of course it’s still there!”

Something tugs in my chest, sharp and painful. I was ready to believe Google was wrong. That In Between had gone under, thwarted

by Amazon and the fact that even twelve years ago it barely had any customers on a good day.

I look back down at the old cardboard box. “What if I came home to help you move?”

More silence. My heart thuds in my ears.

What am I doing?

“Oh,” my mom says. “You want to come here?”

She says it like here is the north pole. Or a swamp. Or the sewers.

Was I really that eager to get out of Oak Falls? Was I really so ready to leave that I made her feel like I thought the whole

town was crap?

Did I think the whole town was crap?

“Well, just to help you move,” I say. “And, you know, while I figure things out. I mean, I don’t have anything else going

on right now.”

I hear another snuffle-snort from Mr. Grumpy in the background. Finally, my mom says, “You can come home anytime, Darby. I’d

love to have the help, and maybe it’ll be nice to see the house again before I move. And I could show you the condo! It’s

quite nice. There’s a whole garage under the building, so I won’t need to shovel in the winter anymore—”

And she’s off, rattling on about this new condo building as though it’s not closing in on ten o’clock where she is, and she

hadn’t just said it was getting late...

But I’m barely listening.

I just offered to leave New York City.

I just offered to go back to Oak Falls.

And I think I want to go.

My friends are going to kill me.

Fullepub

Fullepub