Chapter 9

CHAPTER 9

G erald alive.

Impossible!

And yet…and yet. As much as Joshua was inclined to discard the possibility, he had to consider it. There was the official document delivering the news of Gerald's demise, which should be utterly trustworthy. Joshua had to wonder about battlefields, though, about the difficulty of accurate identification. He could not dismiss the fact that Gerald had not returned home in any form. His brother's remains, such as they were, must be interred near Waterloo. Joshua did not even know if there was a stone to mark the place.

In fact, he did not even know how much of Gerald had been available to be identified.

What if there had been an error?

It was a notion that had never occurred to him, and would never have without Miss Emerson. Surely it was a reminder of Miss Emerson's ability to challenge his expectations and assumptions—which could not be a good thing.

If only this notion were so readily dismissed. As Joshua rode for Addersley Manor, he pondered the possibility of Gerald's survival. There was no evidence that his brother lived. Indeed, there were no bills, which had always been the surest sign of his brother's existence.

But Joshua could not entirely forget Mrs. Lewis' response to the sight of him. There had been something of her declaration that did not sound as if she had been awaiting her lover's return for a decade. The more he reviewed the encounter, the more Joshua had to wonder if Mrs. Lewis had seen Gerald since their son's conception.

Gerald might have survived and found a patron.

More likely, it would be a patroness.

How might Mrs. Lewis figure into such a situation, if indeed there was one?

There was only one way to know for certain. Joshua would have to visit the lady in question.

First, Mr. Newson. Perhaps he might have welcome tidings to deliver to Mrs. Lewis as a result and a respectable reason to call upon her.

He checked his watch and touched his heels to the horse.

Back in London, Miss Esmeralda Ballantyne found herself abruptly returned to her own home. Though she was weakened and much thinner, her spirit was unquenched. Oh, she knew who was responsible for her situation, for the paying of her bills, for the contentment of her servants and the security of her house, even her own release.

And she knew enough of men to guess what the Duke of Haynesdale wanted from her in return. Even the prospect of being the mistress of one man, of becoming even more beholden to him than she already was, chafed at her.

In such circumstance, she might as well be that man's property, one of his chattels, or his indentured slave. The one thing Esmeralda prized above all others was her freedom, and liberty to make her own choices.

But that might have been lost, through no fault of her own.

A curse upon Jacques Desjardins!

If ever Esmeralda had resented that the rules of society and even the law of the land gave more to men than to women, that had been nothing compared to her current fury at the injustice of it all.

She could not deny that the Duke of Haynesdale had a claim upon her—yet she could not entirely explain his willingness to incur her obligation. There had been that old feud between them, and his comments in recent times about her chosen profession showed that his views were unchanged. Why would he even wish for a courtesan as a mistress? His interference in her life would undoubtedly come at a price Esmeralda did not wish to pay.

What could she do about the matter? She paced and she pondered. She would sleep and she would eat, regaining her strength with every passing day. If she called upon him, doubtless he would not see her. She had to wait for him to appear at her door, which did not suit her well.

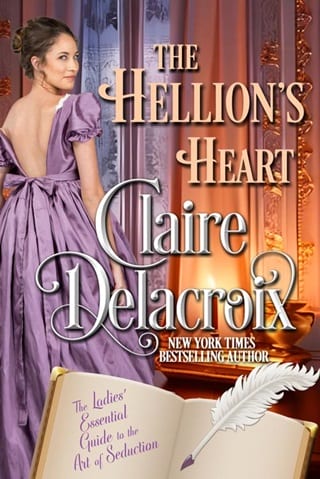

And so it was that she opened her mail and discovered a note requesting that she add yet more to her book in process, The Ladies' Essential Guide to the Art of Seduction .

More.

There was a great deal more advice that she could give.

Without undue consideration, Esmeralda dipped her quill into the ink and wrote a passage to invoke change in her gender.

Upon the matter of feminine capitulation…

It is the expectation of many men, and indeed of society at large, that women should be biddable and docile, always taking the counsel of men with regards to their behavior. I would suggest to you, gentle reader, that there is a delight to be found in challenging such expectations, particularly in matters of intimacy.

In the bedroom, in privacy with one's lover, a lady can reveal her own urges as nowhere else in the world. Be bold in your caresses, and forthright in your demands. Instead of lying back and accepting whatsoever your partner deigns to offer, tell him what you wish of him. Make the first address. Touch him as you wish—or touch yourself as he watches. I have written of boldness before, but the combined power of audacity and surprise cannot be underestimated, nor can its ability to change the foundation of a relationship be overlooked…

Mr. Newson was adamant when finally they met that afternoon, but Joshua had expected a protest from the older man. He was determined to see the question of Mrs. Lewis resolved to his satisfaction. Duty, honor and integrity were his guidelines in this matter.

"I do not believe it appropriate that we discuss this matter, my lord." The older man flicked a baleful glance at Joshua.

"But I would ensure all is set to rights," Joshua insisted.

"All was arranged to your father's satisfaction."

"I fear it may not be to mine."

"I gave my word, sir…"

"And I must defend my name, Mr. Newson," Joshua said crisply, interrupting his manager. "There is a child in Haynesdale Hollow who could be my brother Gerald at six years of age. His name is Francis Lewis and his mother greeted me like a returned lover." Joshua fixed the older man with a quelling look. "I must know the tale and the resolution my father chose."

Mr. Newson polished his pince-nez. "You cannot act upon every coincidence, sir."

"I doubt it is a coincidence. I suspect Gerald was the boy's father and the mother, quite reasonably, mistook me for Gerald."

"It is not your concern, sir."

"It is my concern," Joshua insisted. "If the boy is of my blood, he should be provided for."

"Your father did not share your view."

"My father is dead, Mr. Newson. I insist upon knowing what provisions, if any, were made for Gerald's progeny."

The older man was shocked. "You speak as if there was an entire village of such children! There were none!"

"There is one for certain."

"There were women, to be sure, but they were lightskirts and doxies, every one of them."

"Mrs. Lewis does not appear to be either. She looks to be a respectable woman, albeit one burdened with the obligation of raising a son alone."

"I would not be so readily deceived, sir."

Joshua cleared his throat and straightened. "Tell me, Mr. Newson, or I will find another manager. I must know all that occurs within the sphere of my responsibilities."

"But this was years ago…"

It was in that moment Joshua guessed the truth.

"Was Mrs. Lewis the reason my father bought Gerald a commission?"

Mr. Newson pinched the bridge of his nose. "I swore to keep silent forever," he said heavily. "But I vow to you, sir, your father and I did not know there was a child."

"There is."

Mr. Newson sighed, and took a moment to consider his options. Joshua watched him, knowing his expression was impassive—and not welcoming.

Finally, the older man turned and retrieved a ledger from a bookcase, opening it on the table before Joshua. "Your brother had a habit of seducing young ladies, most of whom, as mentioned, were in the trade of winning the affections of young gentlemen like himself. In London, he spent considerable sums on such women, so much that your father ordered him back to Nottinghamshire."

"I remember the women," Joshua said. "I remember the debts."

But Joshua did not recall Gerald being banished from London to the country.

"I doubt you knew the full extent of it, sir. Your father wished to protect you from your brother's…inclinations." Mr. Newson opened the ledger to a page and offered it to Joshua. There was a list of debts, some paid directly to women, some to dressmakers, furriers, shoemakers and jewelers. The sum at the base of the page was staggering, a culmination of extravagance made by both brothers. One date seized Joshua's attention, the date when all had gone awry, and he anticipated that the spending would at least slow after it.

He had abandoned that life, after all.

But Mr. Newson turned the page to reveal that the expenditures continued and at a much higher rate. Gerald had redoubled his own indulgences when alone in his revels, spending more than he and Joshua had spent together.

"That was for his final year in London," Mr. Newson said. "He nearly beggared the estate, sir."

Joshua sat down, astonished. "I knew he overspent his allowance."

"That tally does not include his gambling debts," Mr. Newson said, his tone heavy with disapproval. "We didn't even learn of all of them until he had left for the Continent." Mr. Newson dropped a heavy finger to the ledger. "You will notice, however, that the spending slows in September of that year."

"And dwindles to very little at all. What expenses remain are from tradesmen in Haynesdale Hollow, not London." Joshua looked up, awaiting an explanation.

"That was when he finally heeded your father, sir and returned to Nottinghamshire as bidden."

"But Father and I were yet in London."

"Aye, and Addersley Manor was closed. It was expected that Master Gerald would open part of the house, but he never did. Your father believed the diminished spending marked Master Gerald's involvement with a young lady in the region, perhaps one of some means." He raised his brows. "I thought perhaps he charmed an affluent widow. You see that they are for provisions rather than clothing, lavish meals instead of horses and carriages."

"I see." Gerald, evidently, had frequented Mr. Darney's inn.

"Your brother came to your father, requesting funds and a settlement for his nuptials."

"He meant to wed her."

Mr. Newson nodded. "He spoke of it, but his lordship would not hear of what he called an unsuitable match. I never knew the lady's name." Mr. Newson coughed delicately. "I also believe his lordship believed the fancy to be a fleeting one, as was characteristic of Master Gerald's liaisons. They argued heatedly—you were in London at the time, sir, when your father came back to meet with Master Gerald—and his lordship chose to buy a commission for Master Gerald. Master Gerald left Addersley Manor immediately to join his company, by his lordship's design, and never crossed its threshold again."

"It was arranged so quickly as that?"

Mr. Newson coughed again. "It is possible that the argument was precipitated by your father's presentation of this plan, and your brother's insistence that he meant to wed was a response. I was not in attendance and cannot be certain." He sighed. "Your father was riled beyond all, to be sure. The tale was not shared with his usual coherence and attention to detail."

Had Gerald even said farewell to Mrs. Lewis? Joshua wondered whether his brother had had the opportunity. Had he truly loved her?

Had Gerald known about the child?

‘You are returned!' she had said, with such joy. It seemed to Joshua that Mrs. Lewis held his brother in affection, even if no one else did.

Had she seen his brother since that day of his departure?

Joshua revealed the note he had received, the second one, and offered it to Mr. Newson. The older man's gaze flew over it, then he looked up.

"You think this is about the child?"

"I think someone believes Mrs. Lewis has been poorly served."

"But she is married. Her name makes that clear."

"I wonder," Joshua said, knowing that his own cook called herself Mrs. Baird but was unwed. He met the older man's gaze. "But I intend to find out. I will not see Gerald's child raised in poverty."

Mr. Newson took a deep breath and frowned. "I understand your impulse, sir, but be warned that people of that class may seek to win an advantage undeserved. Consider the note!"

Joshua found himself bristling on Mrs. Lewis' account. "If she had intended to demand funds from Addersley, would she not have done as much by now?"

"She might have done, sir," Mr. Newson ceded heavily. "Perhaps she awaited your return or that of your father."

Joshua thought she had been waiting for Gerald. "I do not think she wrote this note or the earlier one, but I will uncover the truth."

"You cannot be granting coin to any woman with a son who resembles your brother, my lord."

"Or the line might extend all the way to London," Joshua said flatly. "I appreciate your concern, Newson, but I must repair this situation. The lady lives nearby, Newson, and the resemblance between her son and Gerald is powerful. I will do what is right in my brother's name and memory."

And he might, in the course of doing as much, be able to put Miss Emerson's notion to rest.

The older man caught his breath, grimaced, then nodded reluctant agreement. "We should set a threshold upon it, sir, that your good nature not be exploited."

"We will do what is right, Newson, and that is that."

Joshua felt restless when he returned home. Finding evidence of the occupation at the ruins but not the individuals responsible gave him the sense of a task left unfinished. He could see no way to ensure Miss Emerson's safety, if she did venture from Bramble Cottage, and yet he had no responsibility to defend her.

If she had accepted his suit, he might have insisted that she and her aunt—or she and Becky—come to Addersley Manor until all was resolved.

The fact was that he did not trust her to be sensible.

The very disruption of his usual serenity should have been proof that they were better apart, but Joshua could not dismiss his attraction to her. It was folly. Her presence led him astray and compelled him to forget his habits, but he could not regret a moment in her company.

Even knowing all of this, he felt cheated by his own decision to not pause at Bramble Cottage this day, thereby denying himself even a moment of her company. He felt disgruntled, all for the lack of a certain lady's smile.

He stared across the garden, hands shoved in his pockets, and considered that he felt alive for the first time in a decade. Helena made him smile. Her companionship gave him joy. In her presence, he felt the promise of the future and the wonder of every small delight. And in his heart, he could not truly believe that such an association could be ill-fated or wrong.

How unlike him to be conflicted!

Joshua shook his head, guessing that it was Miss Emerson's habit to disrupt the equilibrium of clear-thinking men.

He found himself unable to keep from imagining her in residence at Addersley Manor. The house felt appallingly empty to him in his solitude and devoid of charm.

He marched through it, seeking some element that would give him pleasure or at least offer a distraction. Instead, he recalled Miss Emerson's favorable comments about this detail or that, and the sight of her in each room.

How had Miss Helena Emerson so securely captured his heart?

It was true. Joshua loved her.

He had loved her from that first glimpse.

It was an astonishing realization. He knew he admired her, of course, and that he found her alluring. But it was more than that. He was enchanted by her lively spirit, her penchant for laughter, even her audacity. She might vex him with her insistence upon following impulse, but in another way, he admired her boldness.

Joshua liked how he felt in her presence.

There was the peril of her. If they were reckless together, dire consequences could result. He could not countenance as much.

He must forget her.

He did not wish to do as much, but it was the only sensible choice.

How curious that for the first time in his life, he had no desire to be sensible!

Joshua was scowling at the interminably long table in the dining room when he realized that something was missing. There should be another pair of sterling candlesticks on the table. He searched the rest of the room but found no sign of them.

He recalled then that the small ormolu clock had also been missing.

In no mood to tolerate thefts in his household, Joshua rang for Fairfax.

Fairfax was clearly shocked that the candlesticks were gone. He was similarly bewildered that the ormolu clock was missing and could not fathom how he had overlooked its loss. "I am shocked, my lord. There has never been any such trouble in this house, and none of the servants are newly arrived."

"Perhaps someone has a new need for funds," Joshua suggested.

Fairfax cleared his throat and looked more prim than usual. "Perhaps it was someone from outside the house, sir."

"But who could have entered the house without detection?"

Fairfax dropped his gaze. "You did have guests, sir, and guests most interested in the décor of your home."

Lady Dalhousie and Miss Emerson? Joshua's astonishment was so complete that it must have shown, for the butler shook his head.

"Older ladies, I regret to inform you, sir, can be…acquisitive when their tastes exceed their means, particularly if they were accustomed to luxuries in the past." He cleared his throat again. "And if I may be so bold as to speak plainly, sir?"

Joshua considered his butler. "Please do, Fairfax. You know that I rely upon your insights."

The older man beamed. "I would say, sir, that my estimation of the young lady was much diminished by her decision to refuse you."

Joshua was touched by his butler's loyalty. "Apparently, she cannot bear the prospect of wedding a man who does not dance, Fairfax."

The butler frowned. "But you had a dancing master to tutor you and Master Gerald, sir. I recall that you both excelled at dancing."

"My father demanded my promise to abandon such frivolities and I mean to keep my vow."

"I can well imagine his disapproval of the excesses possible in London, sir, but dancing?"

"He expressly included it as a deed to be avoided."

The butler frowned. He made to turn away, then turned back again, his indecision and consternation such that Joshua had to ask.

"Is there something you would say, Fairfax?"

"Only that I cannot credit it, sir. I believe your assertion, of course, for you made it, but your father, also, danced himself with notable grace and enthusiasm. Why, he and your mother hosted any number of gatherings with dancing, sometimes as many as one a month." He smiled in recollection. "Your mother loved to dance."

"I do not recall him dancing," Joshua was compelled to note, for it was true.

The butler grimaced. "I fear, sir, that there was only one partner he desired. I never knew him to dance after your mother's demise."

Joshua nodded. "But he danced, you say?"

"Oh yes, sir. If I may be so bold to make a suggestion, perhaps it was your dancing companions in London of which he disapproved."

It could be true. Joshua and Gerald had danced with courtesans, actresses, whores and widows of dubious repute.

They had danced in gaming dens, at gatherings where Cyprians were in attendance, at the theatre and at other venues of dubious repute.

They had danced in various squares, at all hours of the night, and in the dew of drunken mornings. Such dancing had often been accompanied by indulgence in other pleasures, like that of brandy, and invariably led to other excesses.

But dancing at Haynesdale House, under the watchful gazes of dozens of his respectable neighbors, escorting ladies of impeccable reputations, in a sedate and orderly manner, might not fall under his father's injunction.

It was certainly a matter to consider.

Joshua nodded. "Thank you, Fairfax. That is a notion to consider. In the meantime, since we have no good notion of when these items vanished, I see little point in alerting the household to our suspicions."

"Doubtless, they have been sold already, sir," Fairfax agreed.

Joshua consulted his watch. "It is too late to ride to Haynesdale Hollow and consult with the silversmith there, but I will do as much in the morning."

"Excellent, my lord. In the meantime, I would compile a list of every item we know to have vanished. If you might provide assistance, sir. There are some items I have not seen for years, though it is possible your father had them sent to London without my knowledge."

"We will work together, Fairfax," Joshua resolved, opening the console to begin the task.

Even though Mrs. Jameson had called and there was the promise of new satin slippers in Helena's future, the day passed slowly.

It was, to Helena's thinking, a portent of her future at Bramble Cottage—interminable days one after the other, stretching long into her future, only the rare prospect of new slippers to provide a measure of interest.

Aunt had been sorting linens with a vengeance, inspired by Nixon's energetic cleaning of the house to put every detail in order. Mr. Nixon worked steadily for all his casual manner, and made remarkable progress on the overgrown hedges and garden. The surroundings of Bramble Cottage looked markedly more civilized. Becky had finished the mending, happily sitting with the restless Helena most of the day.

Helena had missed her champion. She had missed Mischief. She had missed the viscount, and she recalled the tale he had shared. She was impatient to do more than sit and heal, but had no choice in the matter.

She supposed there was a lesson in that, a reminder that following impulse could lead her astray. There was Mr. Melbourne, a lesson in the price of misplaced trust, and now her ankle, a lesson in the folly of solitary excursions. Try as she might, she could not consider her night ride with her champion to be a lesson in any kind of folly.

It had been lovely and romantic. He was so gallant. Her trust was not misplaced there, even though she was not certain of his name. But what a tale that would be! The viscount's brother, alive and well, returned to Addersley to take her, Miss Helena Emerson, as his bride.

There was a future to dream about.

Yet Helena passed a sleepless night. She was torn between the hope that her champion would come to her again, and the fear that he would not. What would she would do if he did appear? Did she dare to break the injunction against leaving the house alone to meet him? The viscount would not have hesitated to avoid temptation, but Helena knew she did not possess his resolve. How had he abandoned all pleasures, even at his father's dictate, and done so at once? She could not even deny the temptation of one small digression.

In the end, she did not have to choose for her champion did not come.

She overslept the next morning, much to the chagrin of Aunt Fanny. Aunt was always hoping someone would call but no one came to Bramble Cottage. There was no risk in being late to dress.

Helena heard the viscount's horse near noon and her hopes of company rose, but he rode past their gate. By the time Helena reached the hedge, he was no more than a silhouette in the distance—though she knew it was him. She told herself that he was late for an appointment, and that he would undoubtedly halt on his return.

"But you sold them to me, my lord," the silversmith said, his manner puzzled. He and Joshua stood in the man's shop in Haynesdale Hollow, the silversmith wearing his apron and spectacles.

"I most certainly did not," Joshua replied. "When was this?"

"A few days ago." The tall and angular smith pulled out a ledger and adjusted his spectacles. There was a precision about his manner that Joshua liked. "Monday April 21," he read. "A fine pair of sterling candlesticks from Lord Addersley, hallmarked Fraser & Sons London." He turned the ledger so Joshua could read it.

"And yet I have never stepped into your establishment before."

The silversmith frowned and turned the pages of the ledger. "I must disagree, my lord. You tried to sell me a clock not a fortnight ago. I did not buy it, for the sole potential customer for such a token would be the duke, and I know His Grace prefers to acquire his timepieces in London." He shook his head. "I made no note of it, alas, but it was during that stint of rain we had of several days running."

Joshua remembered the rain, and the missing clock. "And you are certain it was me?" He watched the other man, wondering whether he frequently traded in stolen items and was covering for the thief.

The silversmith removed his glasses and scrutinized Joshua. "To be sure, my lord, now that you stand before me, I can see that it was not you. The man who presented himself as you shared your coloring and had your height, he might even have worn that coat or one similar, but it was not you. I recall now that he was inclined to keep his face turned away and he did not remove his hat." The silversmith frowned as he considered Joshua's hat. "It was less fine than yours, to be sure."

The conclusion was evident. Someone in his household or near to it was stealing from Addersley Manor and impersonating Joshua to sell the items. Who could it be? He would ask Fairfax to line up all the staff and judge which of the men was of similar height to himself.

It could be a maid and a man working together, though, in which case the man might not be employed at Addersley. Somehow he would find the villain and put an end to this.

He bought his own candlesticks back, the silversmith offering him the same price he himself had paid to the villain. Joshua thanked him, thinking that more than fair. "Where else might he have tried to sell the clock?"

The silversmith shrugged. "Nowhere in Haynesdale Hollow, my lord. I reckon he would have to go as far as Colsterworth. There is a goldsmith there who sells watches and clocks as well."

Did the thief have a horse or access to one? Joshua could not say. For the moment, he would return home and strive to identify the villain.

Someone must have seen something. A stranger could not enter his home without being observed.

He thought of the notes and wondered if the two might be linked.

Lord Addersley did not halt upon his return that day.

Helena abandoned her tea at the sound of hoofbeats to hasten to the door. But the viscount rode past, seemingly without even a glance in her direction. He certainly did not slow his horse.

Helena was disappointed, for he always brought tidings to them.

She sat up watching for her champion until well after midnight, but he did not appear either. She heard no horse. She saw no shadow in the distance.

It seemed her curiosity was to be punished—as the curiosity of every heroine in every fairy tale was inclined to be. She winced, remembering the viscount's comparison. Had she not touched her champion's face and discovered the cleft in his chin?

She had strayed from the path to wander in the forest, curious to know its hidden charms. She had looked inside the locked cupboard forbidden to her. She had lit a candle to look upon the face of her mysterious lover.

And in so doing, she had lost his regard. Helena knew that as well as she knew her own name. Curiosity was always punished in such tales.

Helena had to find a way to set matters to rights, but if her champion no longer came to her, she could not see how it might be done.

She had a will, though, so there had to be a way.

She thought about that cleft in his chin, and in the middle of the night, she began to wonder. Lord Addersley said it was impossible for her champion to be his lost brother. His conviction of his brother's death had been unshakable. Undoubtedly, he had more evidence than he wished to share, evidence that proved to him that his brother was dead.

Her own brother, of course, might have taken an opposing view to tease her, but Lord Addersley had always told Helena the complete truth, even when it was unwelcome. If he said his brother was dead, she should believe him.

But if her champion was not the viscount's brother, who might he be? It was true that he might be a former soldier, reduced to poverty by the loss of his commission, but Helena doubted such a man would share any traits, even size, with the viscount.

How many men had she ever encountered with a cleft in their chins? Of similar height and breadth? With such elegant manners? At such ease on a horse? Possessed of fine clothing and boots?

Helena frowned at the ceiling. In this region, there was only one man who fit that description. Though she fought against the conclusion, she could not evade it.

What if her champion was the viscount?

What if the viscount had a secret identity, like the highwayman or Robin Hood?

She sat up abruptly in bed, her thoughts spinning.

He would have to have a good reason for undertaking such a disguise, of course, one that required a secrecy that was outside his nature. It was not difficult to imagine him perpetuating a disguise with good cause, or even being evasive about the truth. He was honest, to be sure, and trustworthy, but he was also honorable.

What was the cause?

She could not ask him outright, of course, for if the viscount kept a secret, there must be good cause. He was not a frivolous man or one inclined to jests. Had someone not implied that he had worked as a spy during the war? Did his quest have anything to do with the men who had occupied the ruins?

Helena dared not even hope that his ruse was for her sake. No, she had simply witnessed the truth by accident, by being in the wrong place at the wrong time, and his gallantry had demanded that he see her safe.

There was so much more to the viscount than met the eye!

And Helena wanted to know every detail.

Would he keep their rendezvous at the folly, when her ankle was healed and the weather was finer? Helena wished for that outcome with all her might as the rain fell, pounding upon the roof and ensuring her captivity at the cottage was complete.

When she finally slept, she dreamed of the thawing of a taciturn viscount with a dimple—and in her dream, the viscount kissed with all the beguiling assurance of a highwayman.

Nicholas sent the carriage to Bramble Cottage on Sunday morning, and the family all went to church together in Haynesdale Hollow. Helena spent the service surveying all the young men present, but failed to find one who might be her champion.

The viscount, she could not fail to note, was not there. She supposed there was a church at Addersley village and he was obliged to attend services there, but found herself disappointed in his absence all the same.

The dowager came to Aunt Fanny when they were leaving the church, her delight obvious to all. The reason soon became clear. "I have had a letter from Damien," she confided in Aunt Fanny, her words sufficiently loud to carry to others. "He will arrive in time for the ball, though I had no such expectation."

"How wonderful," Aunt said, granting Helena a significant glance.

Helena sighed, finding herself with little interest of the duke's doings.

"You may have your dance after all, Helena," Nicholas teased but Lady Haynesdale laughed.

"Oh, Damien does not dance. You must know as much Captain Haynesdale. He did not even dance before his leg was injured and now—" she made a sweeping gesture with one hand. She then leaned closer to Aunt Fanny. "The most interesting detail is that he is bringing his ward, a Mademoiselle Sylvie LaFleur."

"I was not aware that Haynesdale had a ward," Nicholas said.

"Nor I!" agreed Lady Constance with a laugh. "But his adventures are legion. Doubtless he will have a tale of it to share when he arrives. He is expecting another guest as well, an elderly lady called Mrs. Oliver."

Mrs. Oliver? Was that not the name of the author of that scandalous advice Helena had found in Eliza's possession? Helena cast a quick sidelong glance at Eliza, whose eyes had widened in alarm. Even Nicholas developed a sudden fascination with the ground before his boots.

Helena was not mistaken then. It was the same Mrs. Oliver. Who was she and why was she coming to Haynesdale at all? She listened avidly, hoping to learn as much as possible of these promising tidings, but the subject was changed all too swiftly.

The dowager said her farewells and hastened away, even as Aunt Fanny watched her go. "A ward ," Aunt said under her breath. "The duke unexpectedly has a ward, who is French." She shook her head primly. "I wager she is young and lovely and of no blood relation at all."

Nicholas laughed. "And you think he plans to wed her?"

"I think the situation utterly obvious, Nicholas," Aunt said primly. Nicholas handed them all into the carriage.

"Then I will take your wager, Aunt, for I know Damien has no intent to marry at all. I am certain that if ever he did take a wife, it would be a lady close to his own age. He has little patience with young ladies."

Helena assumed this was a warning targeted for her ears, but she was less interested in the duke's inclinations than before. Indeed, she could only recall how very elderly he was, and reliant upon his cane. He made no effort to be charming, in her recollection, or even to be polite. The viscount was a much more agreeable companion and much more attractive, as well.

"A pretty young chit might change his thinking," Aunt insisted. "It has happened before."

"Not Damien."

"It is his duty to wed and father at least one son."

"And never has there been a man so disinterested in the expectations of others." Nicholas shook his head. "When do you think he would wed this young lady?"

"I will not speculate upon the circumstances of others," Aunt huffed, although Helena knew she routinely did as much. A wager with Nicholas, though, would reveal her interest in the affairs of others, and in a way that she might deem vulgar as well.

Helena's brother, however, knew the perfect bait.

"A new hat for you if I am wrong," he said and Aunt's eyes lit with predictable interest.

" Any hat?"

"Any hat the dressmaker in Haynesdale Hollow can contrive for you."

Aunt, Helena knew, believed herself in need of a hat, and if one could be had at no expense to herself, all the better.

"And if I am wrong?" that lady asked. "What will you demand for your side?"

"I will be content with the satisfaction of having been right," Nicholas said with a smile.

"I will take your wager," Aunt said as the carriage began to roll. "I will take your wager and teach you a lesson, Nicholas Emerson, about the folly of believing a man cannot change his view. Love," she informed him loftily, "can soften the most resilient heart."

"It will have a quest in claiming Damien's," Eliza said under her breath.

Nicholas laughed and shook Aunt's hand. For her part, Helena looked out the window, marveling that her interest in the duke should have diminished so very much in so little time. It was a puzzle and almost certainly the influence of a docile country life. Soon, she thought with a sigh, she might even find enjoyment in her needlework.

Fullepub

Fullepub