5: Andrés

5

ANDRÉS

Apan

Diciembre 1820

Three years earlier

AS I RODE ACROSS the countryside of the district of Tulancingo, the valley of Apan claimed me like a summer twilight: the bittersweet realization that I was nearly home was soft at first, teasing at the fringes of my senses, then took me all at once, swift and complete. Some kilometers outside the town, I told my traveling companions my mule had a stone in her shoe, and that they should ride on. I would rejoin them momentarily.

I dismounted.

For seven years at the seminary in Guadalajara, the Inquisition hovered over my shoulder like the shroud of death, ever watchful, its clammy breath foul on the back of my neck. From the age of sixteen until my ordination, I smothered my senses, drowning them in Latin and philosophy and penance. I prayed until my voice was hoarse. I wore a hair shirt when instructed it would purify me. I folded up the darkest parts of myself and shoved my contorted spirit into a box that remained locked.

But when my feet touched the earth of the valley, the axis of the world shifted beneath them. The windswept winter countryside and low gray skies turned their sleepy gaze toward me. They saw me, recognized me, and nodded in the slow, satisfied way of the ancient giants. I scanned the low, dark hills that curled around the valley like knuckles: for the first time in seven years, I sensed the spirits who hummed through this small corner of creation even when their names were forgotten.

The valley’s awareness of me overtook me in a roar, in a wave, and I trembled beneath my too-big sarape. For years I had buried myself behind thick walls, alone—my secret severed me from the other students at the seminary. Fear of discovery governed my every thought and step; I hid myself so completely that I lived a hair’s breadth from suffocation.

Now I was seen.

Now, the thing I feared most spread like a shadow in my breast: here, far from the eyes of the Inquisition, the parts of myself that I had shoved into a box began to unfurl, soft and curious as plumes of smoke, testing lock and hinge.

I forced them down.

Tell him I pray for his return to San Isidro. The birds pray for his return to San Isidro.

My grandmother’s prayer was answered. I was nearly home. But what would become of me, now that I was?

* * *MY ARRIVAL WAS IMMEDIATELY consumed by preparations for the feast day of la Virgen de Guadalupe. Padre Guillermo and Padre Vicente had a specific vision for the procession of the statue of la Virgen and San Juan Diego through the streets of Apan, and made it clear what my place in it was: shouldering the litter carrying la Virgen and the saint at her feet alongside men from the town. Padre Guillermo was too old for such things, Padre Vicente said, and he—well, he would be leading the procession, wouldn’t he?

This was my place as a young cura, a sin destino priest with no parish and no hope of a career in a city. This was the proper place of a mestizo priest in the eyes of Padre Vicente. He was correct. More than he knew. Even if I had been a man of ambition, even if I had entered the priesthood with the intention of lining my life with silver and comfort like so many men I met in the seminary, I could not change what I was.

I knew Padre Guillermo from before I left for Guadalajara. How often he had found me asleep beneath the pews in the church as a boy and carried me back to my mother through the dawn, curled in his arms like a drowsy kitten. If Guillermo guessed at the reason I fled from the house in the middle of the night, seeking the silence of the house of God, he never mentioned it. It was he who wrote to Guadalajara and welcomed my transfer to the small parish of Apan, and when I arrived, dusty and exhausted from weeks on the road, he who embraced me. Guillermo, for all his fluster and pomp and his desire to please the wealthy hacendados who funded renovations in the church, was someone I trusted. But still, he had never lived on the haciendas as I had as a child. There were so many things he could never understand.

Vicente was new, a replacement for old Padre Alejandro, who had walked alongside the specter of Death for years. From the moment I met Vicente’s hawkish light gaze, a curl of fear turned in my bones. He could not be trusted—not with me, nor my secrets, nor with the struggles of my people.

The priests exited the church through the back to begin the procession, and I took my place among the three other townspeople elected to carry the litter of la Virgen—the aging master of the post, an equally graying baker, and his whip-thin son who looked no more than twelve. Nine years of insurgency had left no family unscathed. No townsperson, no hacendado, no villager had not lost a son or brother or nephew in their prime. If not in the battles that tore up the countryside and painted it black with blood, then to tuberculosis, or gangrene, or typhus.

I took my place and lifted the litter of la Virgen on my left shoulder. We were imbalanced; my height was not matched by the baker, so I would need to slouch to keep la Virgen at an even keel.

“¿Todo bien, Padre Andrés?”

I looked over my shoulder at the baker’s son and grunted in the affirmative. Past him were the low stone walls of the graveyard. I turned my face away quickly.

More of my family now lay beneath the earth than walked it, but I had not paid my respects to those who lay behind the parish of Apan. My brothers were not there. Antonio and Hildo had died in battles in Veracruz and Guadalajara; only the Lord knew where they rested. The third, Diego, had vanished somewhere near Tulancingo last year. He was alive, I knew it, and was held somewhere, but none of my frantic letters to every insurgent I knew resulted in any reply. My grandmother was not there. She was buried near her home in the village of Hacienda San Isidro. I wished my mother could be buried near her, on the land where she had been born, the land that was home, the land where her family had lived for seven generations, but she was in the cemetery behind me.

I would visit soon. But not now. Not yet.

On Padre Vicente’s command, we began to walk around the church to the plaza de armas. Apan was four proper streets and a tangle of alleys; gray and quiet on most days, it burst at the seams on the feast day of la Virgen. People from the haciendas traveled into town for the Mass and the procession. They were dressed in their feast day best, men in starched shirts and women in bright embroidery, but as we proceeded slowly behind Padres Vicente and Guillermo, it became clear how faded and patched these clothes were. There were too many gaunt faces, too many feet without shoes, even in the middle of winter. The war left no part of the countryside untouched, but it left its deepest mark on those who had the least.

But whenever I glanced up, I saw eyes bright as an autumn sky. Burning with curiosity. Fixed not on la Virgen and rapturous Juan Diego, but lower.

On me.

I knew what they saw.

They did not see the son of Esteban Villalobos, onetime Sevillan foreman to old Solórzano on Hacienda San Isidro, then assistant to the caudillo, the local military officer who maintained order in Apan and the surrounding haciendas. Resident thug and drunk who had returned to Spain seven years ago.

They did not see the newly ordained Padre Juan Andrés Villalobos, a cura trained in Guadalajara, who regularly prayed before a cathedral retablo resplendent with more gold than they had ever seen in their lives.

They saw my grandmother. Alejandra Pérez, my sijtli, called Titi by her many grandchildren and by a good measure of the countryside besides.

It was unlikely they saw her in my features—these were more my Spanish father’s than my mother’s. No. I knew they felt Titi’s presence. Perhaps they even felt the shift of the earth beneath their feet, the attention of the skies tilting toward me. There, they said. That one. Look.

And look they did. They made a show of gazing at la Virgen and crossing themselves when blessed by Padre Vicente’s swinging golden censer, but I knew they watched me beneath Juan Diego’s wooden knees.

I kept my eyes on the dusty road before me.

The people of Hacienda San Isidro were clustered in a group near the end of the procession, at the front of the church. I raised my head and found my cousin, Paloma, standing with a few other girls her age. She shifted her weight from one foot to the other in anticipation, craning her neck, scanning the procession. When her eyes caught mine, a smile illuminated her face like lightning. I nearly stumbled, like Christ on the road to Calvary, from the shock of seeing someone so familiar after so many years apart. I had returned to Apan, yes, but now, in Paloma’s presence, I felt I was home.

They were all there, the people of the hacienda I had known my whole life: my aunt and Paloma’s mother, Ana Luisa, the old foreman Mendoza who had replaced my father in the wake of his indiscretions. They watched me with intense black eyes, taking me in for the first time in seven years, knowing me as their own.

I knew they expected me to step into Titi’s shoes.

But how could I? I was ordained. I had followed the path Titi and my mother urged me to take: I was not lost to the last decade of war, be it by gangrene or a gachupín’s bayonet. I had skirted the attention of the Inquisition and become a man of the Church.

They will teach you things I cannot, Titi said as she put me on the road to the seminary so many years ago. Besides, she added, a sly twinkle in her eye as she patted my chest, aware her palm rested directly over the darkness that lived curled around my heart, won’t you be well hidden there?

The people of San Isidro needed more than another priest. They needed my grandmother. I needed her. I missed how she always smelled of piney soap, how the veiny backs of her hands were so soft to hold, her knobby fingers and wrists so strong and sure as they braided her white hair or ground herbs in the molcajete to cure a family member’s stomach pain. I missed the mischievous glint in her dark eyes that my mother, Lucero, had inherited, and that I wished I had. I even missed her exasperatingly cryptic advice. I needed her to show me how to be both a priest and her heir, how to care for her flock and calmly deflect the withering suspicion of Padre Vicente.

But she was dead.

I closed my eyes as the procession shuffled to a halt before the front door of the church.

Please. The prayer reached out, up to the heavens to God, out to the spirits that slept in the bellies of the hills ringing the valley. I knew no other way to pray. Give me guidance.

When I opened them, I saw Padre Vicente shaking hands and blessing members of a group of hacendados. Their silks and fine hats stood out against the crowds, garish as peacocks in a famine. The old patróns of Hacienda Ocotepec and Alcantarilla tipped their hats to Padre Vicente, their pale-haired ladies and daughters clasping his hand in their gloved ones. Even the hacendados had not escaped the ravages of war. Their sons had left to fight for the gachupínes, the Spanish, and left only old men and boys to defend the estates against insurgents in the countryside.

The only young man among them was one with light brown hair and piercing blue eyes, whose saintly face looked like it was carved and painted for a statue in a gilded retablo. He stood apart from the others and met Padre Guillermo’s effusive greeting with a calculated half smile.

It took me a moment to place why he seemed so familiar.

“Don Rodolfo!” Padre Guillermo cried.

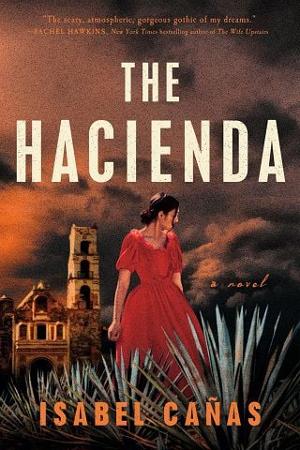

He was the son of old Solórzano. Now, presumably, he was the patrón of Hacienda San Isidro. I had seen him from a distance as a boy on the property; I knew children in the village did not mind him, and even played with him chasing frogs in the creek below the house from time to time. Now, he could not be more different from the villagers: his clothing was finely tailored and cut a sharp silhouette. A criolla woman hung on his arm, whom he introduced to Padre Guillermo as his new bride, Doña María Catalina.

He had brought her from the capital to be safe from typhus, he said. She would join his sister on Hacienda San Isidro and stay for the foreseeable future.

“Does this mean you are returning to the capital soon, Don Rodolfo?” Padre Guillermo asked.

“I am.” He glanced over his shoulder at the other hacendados, then leaned into Padre Guillermo and lowered his voice. “Things are changing very quickly, and the capital is not safe.” His voice lowered further; another man would not have been able to hear him over the general commotion of the crowd, but my grandmother left me with many gifts. My ear, long accustomed to hearing the shifting moods of the fields and the skies, was sharp as a coyote’s.

“You must watch over Doña Catalina, Padre,” Rodolfo said. “You understand . . . my politics are not popular with my father’s friends.”

“May he rest in peace,” Padre Guillermo murmured, his tone and the slow dip of his head subtle assent.

Curiosity sharpened my ears, though I fought to keep my face as passive as a saint’s. To be unpopular with the conservative criollo hacendados, those who clung to their wealth and the monarchy, meant that Rodolfo was sympathetic to the insurgents and independence. It was not unusual for sons of hacendados to turn the tables and support the insurgents, but I did not expect it of the son of old, cruel Solórzano. Perhaps Rodolfo was different from the other criollos. Perhaps, now that old Solórzano was dead, the people of San Isidro would suffer less under the younger man’s watch.

I peered at the woman on his arm. She looked as if she had stepped out of a painting: her small, pointed face was crowned by hair pale as corn silk. Her eyes were doe-like, dark and wide-set; when they flicked in my direction, they slid right over me. They passed over the townspeople, unseeing, and then refocused on Padre Guillermo.

Ah. Those were eyes that did not see faces that were not peninsular or criollo. There were many such pairs of eyes among the hacendados and their families. How could such a woman survive without her ilk, alone in the country, in that enormous house at the center of Hacienda San Isidro? She looked as if she were made from expensive white sugar, the likes of which I had only ever seen in Guadalajara. Unreal as a phantom lilting pale on a riverbank. I had seen women like her in Guadalajara, pious, wealthy women with hands as soft as a lamb’s spring coat, utterly incapable of working. Such people could not survive long in the country.

I wondered then if the changes Don Rodolfo hinted at would end the war at last. Whenever it did, I was sure that his spun-sugar wife would flee back to the comforts of the capital, typhus or no.

How very wrong I was.

Fullepub

Fullepub