64 WITHOUT A MOONWOLVES

64

WITHOUT A MOON OR WOLVES

Once Rackman starts shooting at the fuselage of the plane, the usually phlegmatic Monger becomes excited by the sound of gunfire, almost as inflamed as he gets in more intimate confrontations that involve knives and bludgeons and bare-handed strangulations. He hurries forward from the back of the procession, where he should remain to discourage Vector and Trott from doing something stupid, but when potential violence becomes manifest violence, he is quite capable of being stupid in his own right.

Of Monger and Rackman, the latter has a greater capacity for something like wisdom and for an approximation of self-control, which they both recognize. Indeed, they share a joke to the effect that, as to their relationship, Rackman is the brother and Monger the half brother. They both get off on violence, but Rackman is a connoisseur and Monger an eager enthusiast. They also recognize that on some occasions Monger's reckless bloodlust ensures a kill when Rackman's more carefully considered viciousness might have allowed the target to escape. They admire and respect each other for their different strengths.

And they are equally bewildered that their tedious half sister, Wendy, is committed to their redemption, with no desire to engage in a little satisfying violence of her own. She is a useful Christian, providing them with a home at no cost, cooking their meals, and doing their laundry. This is for the most part a convenient arrangement, but her faith in their potential for righteousness is annoying. If they are able one day to conceive of a lethal accident that no one can prove to have been murder, thereby inheriting Wendy's house and estate without arousing suspicion, they will surprise her with their true contempt. However, considering their reputation, escaping blame for offing their sister is less likely than getting away with other murders, because those who hire them as hitmen are powerful people with a vital interest in ensuring that Rackman and Monger escape arrest and indictment.

So in the current case, Monger can only pretend that it's not this Vida person cowering in the aircraft, that it's his sister. As he joins Rackman and opens fire, he has sufficient imagination to see the bullets tearing through Wendy's body and shattering her skull.

By the time Monger empties the magazine of his AR-15, Rackman has reloaded and is ready to blast away again. In the brief moment of silence between barrages, the echoes of gunfire having quickly faded away through the muffling trees, an unexpected and bizarre event occurs. Monger happens to be looking at his brother when it appears that a long metal bolt erupts from the side of his thick neck, as if he is the Frankenstein monster in a disguise that is suddenly coming undone.

Rackman stumbles sideways into a tree and turns his head toward Monger. He's walleyed, and an eruption of snot hangs from his nose. He opens his mouth as if to ask what just happened, spews blood, and collapses. Dead.

In the aircraft lie four locks of hair that Vida cut off with the wickedly sharp combat knife. Attached to the hair are four tech ticks transmitting the location where the barbering occurred.

She stands in shadows slightly uphill and far to the west of the gathered posse, sheltered on three sides by a stone formation. The raccoon, which she chased from the plane before she departed, has gone its own way.

Although she is perhaps a hundred and twenty or thirty yards from her target, the crossbow has a powerful scope, a maximum-distance range of almost four hundred yards, and no less accuracy than a rifle.

My heart is ready.

The moment she has fired at one gunman, she uses the built-in crank to winch the bowstring into place. She is so well practiced at this, she can perform the task almost as fast as if she manually cocked the weapon with a foot in the stirrup.

The quiver attached to her belt contains high-quality carbon quarrels, and she loads one in the barrel.

With a 150-pound draw, the crossbow delivers the quarrel—–the bolt—at devastating velocity.

Although there is recoil with which to deal, there is no sound of a shot, thus robbing the other men in the posse of the ability to gauge her position with any accuracy.

From where Galen Vector stands, just for an instant it looks as though Rackman has thrown down his rifle and dropped to his knees in prayer. Then the hulk falls forward on his face, and it's impossible to believe that such an arrogant man, who's able to commit extreme violence without a twinge of conscience, would prostrate himself before anyone or anything. Rackman is dead, as though felled by a curse murmured by a voodoo priest a thousand miles away.

Monger turns from the corpse, his brow furrowed with confusion, his mouth open in disbelief, as if he's forgotten where he is and doesn't know how he got here. A horn sprouts from his forehead, just above the bridge of his nose, and the center of his face appears to fold inward as if there's a void behind it.

In defense of my life, of whom shall I be afraid?

Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.

Following José Nochelobo's death and the informative visit from the mortician's daughter, Anna Lagare, Vida acquired the crossbow and a large number of quarrels in a neighboring state, where neither a permit nor an ID was required for the purchase. When this grisly business is finished, when these hateful men are no longer a threat, she can dispose of the weapon in such a way that no one can trace it to her.

When the crossbow is cocked, she quickly places another quarrel in the barrel, making sure to align the vane with the channel, and then nocks it in place.

One of the pursuers pivots in an arc, indiscriminately firing his AR-15, spooked into returning fire even with no target on which to draw a bead.

My life passes like a shadow. Yet a little while, and all will be consummated.

She brings the shooter close in the crosshairs of the scope and gently squeezes the trigger. With a pop! the quarrel flies.

Although Frank Trott has ginned up anger toward his ex-wife to distract himself, nevertheless he keeps thinking of his dead mother gazing up at him from within the barrel before he welded it shut and dropped her in the bog all those years ago. As Monger fires at the airplane and Rackman reloads, Frank realizes it's the fact of Nash Deacon and Belden Bead buried in their cars—their barrels—that's causing him to obsess on the image of his mother. Strong men, hard men, yet killed and packed in their barrels and rolled into their graves by a woman . Neither regret nor remorse is troubling him, after all. He is loath to admit that it's fear, for he's not a fearful man, but indeed it's fear of cosmic retribution that has a grip on him. Then Rackman takes a hit.

Rackman goes down hard, and Monger goes down harder, but Galen Vector is surprised that anything could rattle Frank Trott so much that he would crack and start shooting at bogeys, phantoms, nothing at all, but that's just what happens. When the rifle is out of ammo, Trott starts shouting challenges to Vida while he ejects the spent magazine and jams in a fresh one, screaming his fury at the top of his voice. In those old World War II movies set on islands in the Pacific, the hero always becomes exasperated that his platoon is being pinned down; in an act of courage few mortals can match, he charges up the hill toward the machine-gun emplacement, issuing a cry of outrage, heedless of danger, and takes out the two enemy soldiers hunkered behind a triple-thick wall of sandbags. This is exactly like that, except Frank is turning in a circle instead of charging up a hill, not in a valorous act born out of bravery, but in pure animal terror. Unlike the hero in a movie, Frank is deleted in a flamboyance of blood when a crossbow bolt apparently enters his open mouth and exits the back of his neck.

Sam Crockett has wisely fallen flat to the ground and pulled his dogs close to him. But Vector thinks it's even wiser to admit that the woman they've come to kill is no powder puff, and run for it.

Sherlock, Whimsey, and Marple don't shy from action or trouble. The dogs are lying in hart's-tongue ferns, pressing against Sam as he has commanded, but they're still ready for the hunt. Aware of the tumult among the members of the posse but uncertain of the cause, alert to the gunfire but willing to entertain the possibility that the sound is celebratory rather than evidence of a serious threat, they swish their tails through the leathery fronds of the ferns, panting and shivering with repressed excitement.

For Sam Crockett, it's Afghanistan writ small. He can handle this. Pressed to the ground, he feels and hears his heart measuring the danger, pulse elevated but not racing, clocking under eighty beats per minute. He's never suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome, largely thanks to the company of dogs, to the sense of family and the love they give him. He can handle this.

When Rackman is cut down, Sam is surprised. When Monger is dispatched, astonishment gives way to understanding. Back in the day, in one of the more remote regions of the Hindu Kush, high on those treacherous slopes, a Pashtun villager had chosen to forsake the common AK-47 for a crossbow. He came from a settlement without running water and with an open-pit community latrine, yet from some sympathetic foreign-aid group, he acquired the finest available compound crossbow, a powerful scope made in Switzerland, and a seemingly infinite supply of quarrels with four-sided points. His silent killing had a chilling psychological effect on the men with whom Sam served—but in time they put an end to him.

Immediately when Frank Trott is taken out, Galen Vector decides to split. Obviously, he knows nothing about the strategy of retreat that is most likely to ensure survival. He turns away from the scene with the evident intent to retrace, as fast as possible, the path they followed here. A man's broad back offers an enticing target. And though even an experienced bowman might take ten seconds to cock the weapon and nock the quarrel and take aim, no one is fleet enough to outrun a projectile with a range of a fifth of a mile and the power to punch through plate armor. Judging by the way Vector falls between one step and another, without a cry, and lies as motionless as the stratified rock of which the mountain under them is formed, Sam concludes that the quarrel cored his heart.

He knows little of the woman slated to be murdered, only that the Bead family and Terrence Boschvark want her dead; that whatever she might be, she is not one of them; that whoever she is, she is extraordinary. If she knows her enemies so well that she is at all times prepared to deal with them so decisively, even when they are as amoral and vicious as the crew that now lies scattered across this killing ground, then she must know—or at least possess the capacity to consider the possibility—that Sam poses no threat to her.

He dares to rise from the ferns, and at his command the dogs get to their feet as well. Sherlock, Whimsey, and Marple no longer wag their tails. Their excitement has subsided to tense caution and keen interest. They raise their heads, nostrils flared, drawing from the air a scent too subtle for Sam to detect—the ripeness of warm blood, a sinister smell woven through the odors of the forest mast and the piney fragrance of the evergreens. The aroma doesn't excite them; each dog in turn meets its master's eyes, and every gaze is solemn, as is required even by the deaths of men like these.

After a minute or so, movement to the west draws his attention. Carrying the crossbow but not holding it at the ready, the woman approaches through a distribution of light and shadow as entrancing and mysterious as the chiaroscuro in any work by Rembrandt. Even outfitted in hiking gear and on this broken ground, she moves with consummate grace, as if the land is being reshaped by some higher power to facilitate her progress.

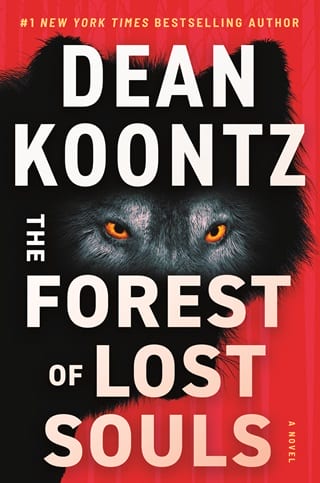

As a boy, Sam had numerous enthusiasms. Trains, their lore and history. UFOs. The United States Marines, their triumphs and their sacrifices. Who built the pyramids and how. The myths of the ancient Greeks and Romans. As Vida strides toward him, he recalls a picture in a book that fascinated him when he was twelve—an Art Deco image of the goddess Diana on the hunt with bow and arrow—and he thinks this scene before him should be unfolding in the haunting light of the full moon, with attendant wolves accompanying her, as in the painting.

When she arrives, the dogs whimper with delight and wag their tails. They want to go to her, and Sam gives them enough leash to do as they wish.

The woman puts down the crossbow and drops to one knee. The dogs nuzzle her hands, and she strokes their faces.

When Vida gets to her feet, Sam indicates the four dead men. "I'm not a friend of theirs. They deceived me to get me here. I don't mean you any harm."

"I know," she says. "I saw you in a dream. I was sitting on my porch with a fortuneteller. The moon was four times its usual size, enormous. You and the man I would have married, if he'd lived, were standing in the yard, looking up at it."

She stops within arm's reach of him, and he is self-conscious about his face to a degree that he has not been in a long time.

"What's your name?" she asks.

"Sam. Sam Crockett."

"I'm Vida."

"Who was the man you would have married?"

"José Nochelobo. Did you know him?"

"Not personally. He was the high school principal. The football coach."

"And more than that. They killed him for being more than that."

"They said he died in a fall or something."

"They say a lot of things."

Sam surveys the four dead men. "So this is vengeance."

"No. I didn't seek this. They did. I want justice, not revenge."

"But it's done."

"Not nearly."

The dogs sit at attention, watching her, rapt.

A stillness has settled through the trees. The forest was familiar to him a moment ago. Now it feels like a strange place, almost unreal.

"Where did it happen?" she inquires.

He doesn't need to ask what she means. "Afghanistan. Saves me having to buy a costume every Halloween."

"Don't say such things. You served your country at great cost. That's noble. It's a noble face."

He does not respond. People say such things because they think they should.

As if she can read the thoughts that live behind his eyes, she says, "I'm not blowing smoke. I never do. When I see you, I see kindness."

After an awkward silence during which an apt reply eludes him, he reaches for something—anything—to say. "Feels weird."

"What does?"

"Standing here with four dead men. We should go. Somewhere."

"I didn't want to kill them, but I'm not sorry I did. The sight of them doesn't bother me. They're finished bothering me."

So he says, "A fortuneteller? White robe, yellow sneakers?"

"Yes."

"Then not only in your dream."

She studies him a moment before she says, "How old were you when you went to her?"

"Thirteen. My dad had left us. She reassured me that my mother could get past the betrayal and be happy again."

"What did the seer tell you about yourself?"

"To expect great suffering and sorrow."

"Afghanistan. What else?"

"That later there would be dogs in my life and ‘new heights of happiness.'"

"And are you happy?"

"I won't say it's the heights. But it's good. I love the dogs. They need me. It's good to be needed. I'm grateful to wake up each morning. What did she tell you ?"

"That I would be a champion of the natural world."

He frowns, though she might not realize it's a frown in a face reconfigured by fire. "What does that mean?"

"I guess part of what it means is getting justice for José and stopping Terrence Boschvark's project."

Indicating the dead men, he asks, "Isn't this justice enough?"

"No."

But for their voices, the quiet in the forest seems to have gotten heavier, like the hush after a deep snow when the wind has stopped and neither the birds nor other creatures have ventured forth into the cold.

He says, "What did the seer tell you in the dream? You're sitting there on the porch. The moon is four times its usual size."

"She told me, ‘Be not so foolish as to cling to what was, rather than embrace what can be.'"

"That lady was nothing if not enigmatic. Any idea what she meant?"

Vida locks eyes with him. In her stare there seems to be an answer to his question. But she says only, "I need help to stop Boschvark."

If she isn't the most beautiful woman he's ever seen, he can't remember who was. Whatever he thinks he sees in her eyes cannot be what is really there. Even before his face was disfigured, he would not have been able to charm someone like this, and certainly he can never be with her now that he's become what he is. This isn't Paris, and he doesn't live under an opera house, but he entertains no illusions about his romantic prospects. He has everything he needs. Wanting something beyond his grasp, failing to achieve it, he might risk what happiness he now has.

He says, "Boschvark is worth like a hundred billion. I make my living with a pack of search dogs."

"It doesn't take money to stop him. It takes truth. Truth, courage, hope. That's what the seer meant."

"You think all this with her was—what?—supernatural?"

"So do you, even if you can't quite acknowledge it."

"Maybe. But then ... What fortunetellers usually do is they string words together such that you can make what they say mean whatever you want."

Vida smiles and shakes her head and once more drops to her knees among the dogs, which lavish her with affection. "You and your pack here—who do you search for?"

"Escaped prisoners, people operating meth labs so deep in the mountains they think no one can track them, lost children, people with Alzheimer's who wander away from home, anyone who needs to be found."

She says, "Important work."

He shrugs. "The dogs do the work."

"You must know the county well, these mountains."

"I don't belong anywhere but here. The people have changed some, but the mountains never have."

"Not yet." She looks up from the dogs. "You know the Smoking River, where it is?"

"That's not an official name. It's a place along the Little Bear River, three hundred yards from end to end, where geothermal vents introduce enough heat into the water to make steam rise from it. About as remote as any place gets. A long time ago, it was a sacred spot to some Native Americans in these parts. Most have no knowledge of it, left it behind with memories of so much else."

"Two moon," she says. "Sun spirit."

"I know them."

"Them?"

"They use only their Cheyenne names. Sun Spirit is the wife of Two Moon. They've chosen a life of hermitage. They live just south of where the river smokes."

When Vida gets to her feet, the three dogs are seized by a new excitement expressed in whimpers of pleasurable anticipation, as if some purpose that has gripped the woman is one they can endorse.

"How far to this place south of the smoking river?"

"From here, if you have the stamina to stay on the move until nightfall, then start out at first light, you could be there by ten o'clock tomorrow morning, noon at the latest."

"That's way beyond the woods I'm familiar with. I'll hire you to get me there."

"Get there why?"

"I don't know."

"You don't know."

"But they will."

"Two Moon and Sun Spirit?"

"Yeah. Somehow, I'm sure they know something I need to know. Get me to them."

Fullepub

Fullepub