12 DISTANT CRIES

12

DISTANT CRIES

She spends the rest of Tuesday afternoon in her workshop, where the tumbler-polisher continues to prepare the sapphires, which she checks on from time to time.

The large chrysoberyl is rough and requires cobbing, a light hammering to knock away brittle material. This done, she moves to the trim saw. The six-inch circular blade, cooled by running water, rotates at four thousand surface feet per minute. The risk to her fingers—the stone is handheld—is the greater hazard, though she wears a welder's shield to protect her eyes. She needs to begin by giving the chrysoberyl a flat bottom, for the cat's-eye effect is best achieved by shaping the stone en cabochon . Close attention as well as much patience are required, and she is at the job for some time. In her current circumstances, the work is a blessing, because such concentration is required that her encounter with Deputy Deacon recedes so far to the back of her mind that it might have been an unpleasantness experienced years earlier.

When the bottom of the chrysoberyl is rough-sawn flat, it needs to be subjected to grinding, first with coarse silicon carbide and then with finer abrasives. Grinding will be followed by sanding. When the sanding is done, the bottom of the cabochon will receive a preliminary polish before she shapes the remainder of the stone. She might finish the process by late Friday afternoon.

With the stone sawn flat, she has accomplished enough for the day. She turns off the light and goes to the kitchen to prepare dinner—buttered fettuccini with peas, dusted with Parmesan. She prefers the delicious Morchella conica cut and raw atop the pasta.

Before attending to dinner, she raises the pleated shade, removes the screen, and cranks open the window beside the back door. The sky is so red that the pale grass of the meadow appears to be afire, and the forest is as black as char.

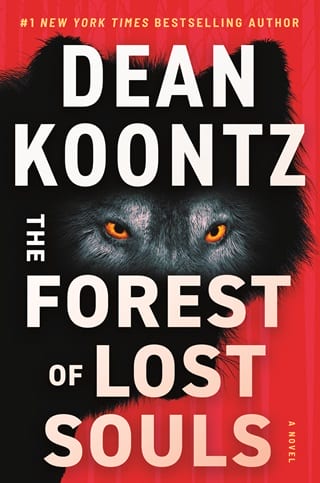

Perhaps she hears them calling in the far distance, though she might be imagining the sound. They howl to warn others from poaching game on their territory, to call the pack together after a hunt, to mourn the loss of one of their own, as well as for other reasons, and every cry that issues from them is of a different character. At times they howl for the sheer pleasure of being together, and though this is a sweet sound, people who are not trained to distinguish one cry from another are nonetheless chilled by it. Wolves were once eradicated from this region; now they have a home here again, though their lives are hard and their numbers small. Their voices are a kind of music to Vida, and she doesn't fear them. They don't attack people. They kill only to eat. They don't kill for pleasure and then leave the prey to rot. They never kill their own kind. Vida listens, and the tepid breeze, infused with the scents of field and forest, carries the sounds of birds going to their roosts and toads waking to the promise of an approaching moon. If the wolf cries were not imaginary, they have quieted.

Fullepub

Fullepub