Prologue

CAROLINE, DUBAI, THE PRESENT DAY

It is time to begin.

I am standing at a podium in front of a painting in an art gallery in Dubai. It is not a large painting—30 inches by 21 inches, to be precise. It is not a very large gallery—we are in the biggest of its three rooms, a white-painted space about the size of a school classroom. Arranged in front of me are several rows of folding chairs, occupied by reporters. I have already been introduced to a writer from the Telegraph and the Gulf News podcast team. A group of press photographers are clicking away, flashguns strobing. At the back are two TV crews, one from a local Arabic station, one from BBC News.

Beside me at the podium is the owner of the gallery, the organizer of this press conference, Patrick Lambert.

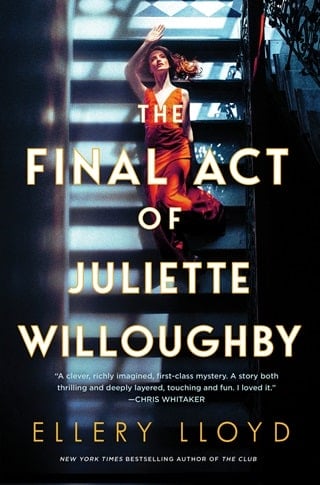

"Dr. Caroline Cooper," Patrick is saying, "is a Fellow of Pembroke College and professor of modern art at the University of Cambridge, specializing in the Surrealist movement in the 1930s, with a focus on Surrealist art by women, in particular the British painter Juliette Willoughby."

Patrick lists my publications, highlighting my 1998 biography of Juliette, the first ever written and still—he reminds everyone—the definitive account of the artist's life, work, and untimely death. He also mentions how long he and I have known each other. One or two audience members smile knowingly.

The painting on the wall behind us is entitled Self-Portrait as Sphinx. It was painted by Juliette—then twenty-one years old—in the winter of 1937–38, and was first displayed at the era-defining International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris in 1938. For decades it was lost, believed destroyed. Last night it was sold, right here, for £42 million.

"Thank you, Patrick," I say as he takes a seat in the front row. He gives me a wink. I stifle a smile back.

I have been asked to keep my speech short: just five minutes in which to explain Surrealism, its historical context and underlying philosophy. To convey why this artwork matters, why I believe it to be genuine, and why I am prepared to stake my professional reputation on that opinion. To tell the story of the artist and this painting, and how it was lost, and how it was found again—twice.

It is a story that begins one wet autumn morning in Cambridge in 1991, at our first dissertation supervision with Alice Long, with the conversation that set Patrick and me on a path that would eventually lead us to Juliette's lost masterpiece.

It is a story that begins one winter evening in Paris in 1937, when a runaway British heiress embarked, in the cold and cramped Montmartre studio she shared with her famous artist lover, on one of the most remarkable paintings of its era.

It is also, I suppose, the story of Patrick and me. How we fell in love. How a painting brought us together, drove us apart, and now seems to have united us once more.

Of everything I have to say, I am aware that thirty seconds at most will make it onto TV, a sentence or two into the newspapers. The headlines will be all about the sum the painting sold for, and who bought it.

What I really want to tell everyone in this room is: Look at it. Look at her, I almost said. Because it is her you notice first. The work's dominant central figure. Her wild auburn mane. Her ice-blue eyes. Her expression: defiant, fearless. Then you notice her breasts are bare. Then you notice there are six of them, arranged like the teats on a cat. Then you notice she has a cat's legs too, a cat's haunches, tortoiseshell-patterned. Sharp claws. And you start to wonder what it might mean, to depict yourself as a Sphinx. As this Sphinx.

Only up close can you truly appreciate the painting's vast intricacy, the people and creatures arranged around the central Sphinx, all intent on their individual tasks, seemingly unaware of one another, in a setting that is part overgrown English country garden, part junglescape. Each new group you notice inviting reflection on the story that together they might tell, your initial bewilderment perhaps fading, perhaps deepening, as patterns and echoes emerge and new mysteries present themselves.

The mystery that the journalists in this room are interested in, of course, is a far simpler one: how can this impossible painting exist at all? The answer is that I am not sure. All I can confidently state is my belief in its authenticity, which means we need to reconsider everything we thought we knew about Juliette Willoughby, her life, and her work.

As it turns out, in the end, I don't have time to say any of that. I have just wished everyone a good afternoon when there is a commotion at the doorway—three latecomers have loudly barged in, asking the same question repeatedly in Arabic. Someone turns to shush them. I am just about to point out that there are still some empty seats at the front when I notice they are in uniform: khaki shirts and trousers tucked into shiny black boots, with angled gold-badged berets. A gallery assistant points out Patrick and they make their way in our direction. I am still—somewhat distractedly—talking about the painting. Patrick, frowning, is out of his chair and advancing to meet the men. The photographers are snapping away, the TV cameras are rolling.

Capturing for posterity and a global audience Patrick Lambert's arrest for murder.

Fullepub

Fullepub