Chapter 6

Chapter 6

We wait until cover of night to steal toward the astronomical observatory. Judging by my experiences in Old Scotland so far, the few renegade humans—and the wild dogs—that remain congregate in and around the cities. If we don’t want trouble, better to keep as low a profile as possible whenever we leave rural areas.

Over these eight days of travel, there’s been no sign of pursuit, warbot or otherwise. I suspect the hunt has been called off. Outright war would be enough to recenter everyone’s priorities, including the powers that be in Fédération and Dimokratía. I suspect the warbot was sent by Fédération, not Cusk—surely Ambrose’s mother wouldn’t kill her own child. So maybe she’ll send her own search mission once she’s greased the right wheels and lined the right palms. But there’s no sign of one yet.

The University of Glasgow has held up well, considering no one is here to maintain it. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised—what are a few years of abandonment for a complex that’s already managed to stay standing for over a thousand years?

The fly launcher is at the roof of the observatory, which Dimokratía had commandeered as a strategic resource for the eight years before abandonment. The bottom floor has an impregnable door with a keypad beside it, still glowing green. Even after Dimokratía withdrew from the region, they left behind military-grade locks to secure their secrets. Locking up our data is something Dimokratía has always been better at than Fédération.

Since this area is seeded with EMP dust, which prevents access to the live databases for passkeys, this lock would have reverted to the saved serotypes deep in its memory. Access would be limited to Dimokratía politicians, generals, ambassadors, members of the space program, anyone who had clearance as of whenever the EMP dusting happened—which I believe was in 2468.

Which means that my serotype is saved in that keypad.

“Stay back here,” I tell Ambrose, sitting him on a mossy stone bench while I approach the door solo. The locking tech is sophisticated, and I don’t want the door to pick up on his serotype instead of mine and activate its defenses.

I stand before the panel, and it reads the tiny blood cells that are available on the microsurfaces of my skin. I wait while the system processes. If it’s gotten on a network since the EMP dusting, or if a Dimokratía representative came through and updated the database, we’re not getting in.

Ting.

“Door’s open!” I call back.

“Good blood you’ve got there,” Ambrose says.

“It might not be Alexander the Great’s, but it’s still useful,” I say. Ambrose snorts.

We make our way up a musty stairwell, our only illumination a torch Ambrose rigged this morning from a stick and my sweaty old socks soaked in oil. The Dimokratía locking system and other essential military tech run on a nuclear cell that will last for at least a hundred thousand years, but luxuries like lights and air handlers relied on the Glasgow power grid, which has long been EMP-dusted out of operation.

“It’s good for us that the launcher was considered essential, huh?” Ambrose says.

“Indeed. It would take a lot of oily socks to power that,” I say. “I’m still a little worried about the more minor electronics involved. I remember these launchers having manual dials, precisely for wartime resiliency, but beyond that, who knows what circuits might be inside that the EMP dust—”

The stairwell trembles. A cloud of soft dust falls from the landing above us. We hold still, faces lit only by the uneven light of the torch, watching its greasy black tendrils illuminate motes of mold and the stray hairs of long-dead scholars.

“What do you think that was... the warbot?” Ambrose asks.

I shake my head. I have a suspicion what that was. But there’s nothing we can do about it if I’m right. “Come on, to the roof,” I say, then begin taking the stairs three at a time.

I throw open the door. The stars shine brilliantly above us, the sky behind them a deep black.

“No sign of the warbot,” Ambrose says, peering into the street below. “Not that I can see very much in this dark. And look—the last moment of sunset.”

I scan where he’s pointing. The bottom of the sky has an orange tinge. “That’s the wrong direction,” I say. I point to the west. “The sun set over there, about an hour ago.”

“Oh,” Ambrose says.

Oh, indeed. Neither of us needs say anything more. We peer into the glow for a long moment.

Of course the warbot was called off. The war has turned nuclear. Nuclear war will eliminate us as efficiently as any warbot. If Cassandra Cusk plans to somehow rescue her prized golden boy in the midst of world war, she’d better hurry up.

I allow a moment to mourn our lives that might have been. Then I’m in motion. “We need to get the fly launcher initialized. Now.”

We take a moment to record messages to our—potentially alive—future selves. The missives are awkward and clipped, shocked and stammering. They can hardly be reassuring for the exocolonists who will one day listen to them. But we get the information across about what’s happened.

Then we settle in to prep the flies. Ambrose takes charge. I know my way around tech, but despite its hasty Dimokratía labeling, this fly launcher is clearly of Cusk origin. He changes the interface language back to Fédération and gets to work, head inclined to the screen, whispering lines of code. I hold the torch for him and stare out the window of the lab, watching for any sign of additional nuclear strikes.

For us to have felt the vibration of that explosion but not the heat, it had to have been far away indeed. Former Spain or Morocco, maybe? Depending on the direction and speed of the wind, we’ll eventually be dealing with radioactive debris in the air. The question is how much of it. This installation is bound to have some anti-radiation meds, and I know Ambrose wouldn’t have traveled into hostile territory without plenty of his own. But there’s only so much radiation that medications can correct for. And no medication can prepare a body for direct nuclear blast.

The torch has served us well thus far, but I’ve just added the second and last oil-soaked sock I have. I have to turn the torch this way and that to avoid burning myself as cotton embers free themselves and drift down to my wrist. “How many flies are left?” I ask.

Ambrose looks up. “There was a good supply here, probably intended to communicate with the Dimokratía moon bases during solar storms, before lunar withdrawal ended all that. There are twenty-three total, three left to go. I’m setting the speeds so that there will be ten-year windows between arrivals, giving us nearly two centuries of error for the Coordinated Endeavor ’s arrival time. Which isn’t a lot, really, when the journey is estimated to take 30,670 years.”

I nod. Twenty flies have already been sent. Even if there’s another explosion nearby, even if we’re vaporized this instant, there’s still a chance our schematics will arrive on the second planet orbiting Sagittarion Bb. Maybe they’ll just sit there, never seen, because the Coordinated Endeavor won’t have made it. If there’s extraterrestrial life already on the planet, maybe those aliens will be poking at the flies and wondering what gods sent them. We could change their civilization forever.

I can recognize Ambrose’s movements at the dial by this point, predict the knocking sound of the launch of the next fly every four minutes or so.

This latest blast is followed by a deep rumble, as if the sky itself is roaring in pain at the bullet that we’ve fired into it.

Ambrose looks up again. “That’s...”

“Not from the fly,” I say.

“Two more left now,” he says grimly.

We don’t hear any more nuclear rumbles before the last flies are on their way. “Good timing,” I say, letting the charred stick drop to the ground, a torch no more.

We’re left in darkness. Ambrose flicks a switch, and the launcher sighs as it powers down. I listen to him breathe. “To the roof?” he proposes.

I check my meter for any signs of radiation. Nothing yet. “Take my hands,” I say. If I’m about to die, I’m going to hold those hands of his at least once. I extend mine, and slowly, fumblingly, Ambrose finds them in the darkness. I pull him in close, like the step of a dance, and then bring us to the roof. We take the steps cautiously, stumbling only once. We pause at the heavy door leading outside. Ambrose’s hand is warm and strong, with some tension sweat. I can’t resist; I graze my lips against his palm, close my eyes at the wonder of being so close to his skin.

Up on the roof, we rejoin Sheep, who presses her side against my thigh, bleating. I feed her some chives from my sack, stolen from the garden of an abandoned cottage we passed as we headed into the ruined city.

Another rumble, and this time we see the blinding flash and the mushroom. “We should get down below,” Ambrose says.

“We have another half hour at least before the first radiation arrives on the wind,” I say.

“The lab has shielding,” Ambrose says. “That’s where we should be. With whatever supplies we can find.”

Neither of us moves, though. I want to watch the explosions, but of course Ambrose is right. If there’s any hope of survival, we need to prepare now, in this brief window before isotopes or nuclear strikes themselves make it here. Right now, cities somewhere are falling. Millions must be dying. The strikes are probably starting in places where they’ll inflict the most damage. But there are enough warheads to hit every region in the world many times over. Including Old Scotland. The fact that we were capable of sending twenty-three flies from here proves that this area is worth a military strike. I know the decision I’d make, if I were in command.

We head downstairs. I don’t take Ambrose’s hands this time, because I’m carrying Sheep. We pass into the laboratory. I don’t have another torch, but the glow at the southern horizon has spread to the east and west, which means we have unnatural orange light coming through the reinforced windows now, lighting surfaces and bodies.

I settle Sheep on some blankets in a corner while Ambrose seals the door as best as he can, covering the seams with old-fashioned duct tape. I pull out my anti-radiation meds and start inventorying, separating them first by type and then by potency. Wondering if we can afford to use any on Sheep.

“Two weeks of water, three weeks of food,” Ambrose reports. “We should save those anti-radiation meds for after we have to leave this room, then they can last longer.”

To have his level of optimism. We won’t need any of that is what I don’t say. Those strikes are quickly getting closer. I clench my teeth against the anguish rushing up from my gut, storm water rising over a drain gate.

“Done,” Ambrose reports, turning around and looking at me. “Kodiak, what is it?”

My desperate thoughts have gone to Li Qiang, my erotiyet from the academy. We stopped speaking to each other after I beat him out for the spot on the Aurora. But before then, he’d been the closest I’d ever gotten to not feeling alone in the world. His touch had been a cure for loneliness that was better than anything that could be spoken aloud.

This sort of tragic ending doesn’t make me sad. It’s what I’ve always suspected I would have. I don’t want to tell Ambrose that he’s about to die, not if he doesn’t already know it. But I do know it. And I know what I want to do with my final minutes, if he is willing.

There’s only one way to find out if he is willing.

I take the two steps to him. I place my hand at the back of his neck, working my fingers through his overgrown hair. The orange light of the nuclear explosions glints on his skinprint mods as I crush my lips against his. For a moment he’s still. Then he pulls away. “Kodiak, what is this?”

“In case, in case we, I just wanted...”

Then hands are on either side of my face, and it’s him. Ambrose before me, the gentle arc of his parting lips, his eyes looking into mine. I kiss him. Move my palms to his head, so my thumbs are pushing into his cheekbones.

Ambrose presses his body against mine, belly to belly. His arms loop under mine, press his body tight, so there’s no space between us. My skin tingles as Ambrose lowers the back neckline of my shirt, kisses the tops of my shoulders. I sigh at the human release of it.

Then his hands are under my fustanella, fiddling with the leather, working their way along my undergarments, fingers touching flesh that hasn’t been touched in a very long time.

The ground rumbles, but we don’t stop. The window strobes white, then the orange glow returns.

For a moment we’re still, and then we continue. I’m on the floor beside him, beside this human who has invited me to lie beside him. Who is slaking this need. It’s so utterly kind that I cry. I am crying.

Ambrose kisses my tears while his hands disappear into the dark below my hips, working expert hands under my Dimokratía garments.

Another strobe and a much deeper rumble, one that hits us like a physical blow, knocking us over. The window shudders so hard that I know it has to shatter. But it holds. Sheep bleats.

“Ambrose, what will our future be?” I ask him as I run my hands over his body, trying to learn something I desperately need to know, that I have to study as fast as I can.

He doesn’t answer. The question is too big to answer. I meant the future some other version of our selves will have. I don’t need to wonder about the future of us, here, now. That future is short. I will live in these current moments as fully as possible. Then I will be gone. Ambrose will be gone. Sheep will be gone.

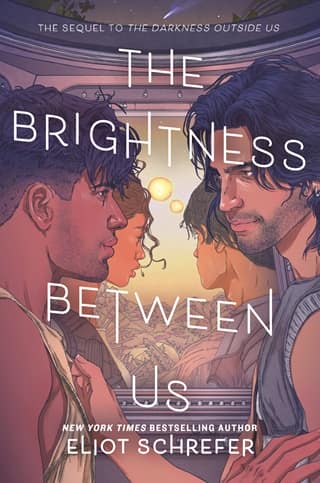

It arrives. The brightness between us.

Fullepub

Fullepub