Chapter 7

7

THE GREEN TESLA SNAKED ITS WAY DOWN THE VERDANT BACK ROADSand into the center of Barlow Corners as day was falling and the shadows were growing long. Nate was absorbed in reading something on his phone, and Janelle was texting Vi. Everyone in the car seemed to be somewhere else. Looking out the car’s window, Stevie noted how different the place looked at various times of day. In the morning, the trees glowed with halos of sunlight, and everything had a freshness and vibrancy that could not be denied. In the heat of the afternoon, the trees were a welcome umbrella from the sun, which still wiggled its way between them. As the sun began to set, however, things took on a strange quality. The spaces behind and around the trees stood out in sharp contrast to the bright places. They were holes, places where things could vanish or emerge into the tranquil town. Doorways.

She wrinkled her nose to dismiss the thought. This is how she had learned to release some of her anxiety—thoughts may come, but she didn’t have to follow them everywhere they wanted her to go.

They pulled up to the curb by the library. The poles and other materials they had seen on the green earlier were now replaced with several marquee tents, linked together into rooms. There were string lights all around the square. People had already gathered and were sitting at the tables. There was a sound system set up, and a DJ pumped out a standard wedding mix of songs that any crowd could tolerate.

“I have to check on a few things,” Carson said. “Go get something to eat and meet me back here. Keep your eyes peeled.”

Stevie had no idea what, exactly, she was supposed to keep her eyes open for—and that felt like both a fair confusion and a personal failing at the same time. She was working this case now, which meant she had to take everything in, but part of working a case is knowing what to take in and not getting distracted or overwhelmed by the hugeness of the world and its innumerable rabbit holes.

Carson didn’t skimp on the food. There were a dozen food trucks parked along the street, serving up tacos, lobster rolls, vegan bowls, corn dogs, and ice cream.

“How much money is in the box business?” Nate said, looking around at the tents and food trucks.

“Enough,” Janelle said. “People like boxes, I guess.”

“But this is weird, right?” Nate went on. “Building an addition to a library, throwing a party, all to get a town to like you enough to talk to you for your podcast?”

Janelle shrugged in a Nate makes a good point kind of way.

“A lot of things work that way,” Stevie said. “Albert Ellingham used to throw big events to get Burlington to support his academy. Companies do it all the time—‘Forget about how we’re destroying the environment, here’s a free hat.’ That kind of thing.”

Janelle gave another This is also a good point gesture.

“I’m still going to eat a lot of tacos,” Nate said. “But I’m going to do it judgmentally.”

They wound around the trucks and were soon carrying more food than they could reasonably hold. As they made their way to a table, Stevie noted Carson supervising the unloading of some video equipment and directing where he wanted the cameras to go. He came over and joined the group.

“I’ve got almost everyone here who was associated with the murders who still lives in town or nearby,” he said in a low voice. “Right ahead of us, blue T-shirt, with the man in the green shorts—that’s Paul Penhale and his husband. He’s the town veterinarian. It was his brother, Michael, who got run down by Todd Cooper seven months before the murders.”

Paul and his husband were talking with Patty Horne, from the bakery.

“You met Patty before,” he said. “And Allison. Over there, white T-shirt and white baseball hat . . . that’s Shawn Greenvale, Sabrina’s ex-boyfriend. It took a lot to get him to come. He owns a water sports business—kayaks and canoes and things. I sponsored a bunch of free rentals, so he had to show up. That older woman sitting in that group over by the trees? The one with the striped top and the short hair? That’s Susan Marks, the head of the camp in 1978. And that . . .”

He waved to a woman in a gray linen suit, which was out of place with all the shorts and light dresses.

“Hang on,” he said. “I have an important introduction to make.”

He stood and signed to Allison, who was coming out of the library. She approached the table.

“Allison!” Carson said. “It’s going pretty good, huh?”

“It is,” Allison said, looking out at the festivities. “It’s very . . . My sister would have appreciated this. We already have a crowd of kids in the reading room playing games and picking up books.”

The woman in the linen suit had reached the table.

“Oh, this is Sergeant Graves,” Carson said. “You know each other, right?”

Allison shook her head.

“I know you,” the woman said. “Or of you. I’m a cold case detective, and I’ve been assigned . . .”

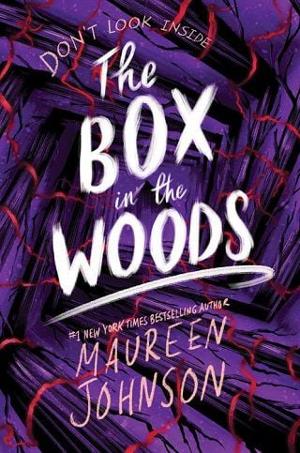

The unfinished bit of the sentence indicated that she had been assigned to this case: the Box in the Woods.

“Nice to meet you,” Allison said, shaking the woman’s hand formally. “You know, we get someone new every year or two. It never comes to anything.”

“I’m aware of that. It must be very difficult for you. But I want you to feel free to reach out to me anytime at all. Here.” She reached into her bag and produced a business card. “Anytime. I’m happy to talk, to answer any questions I can, whatever you need. Consider me a resource.”

Allison took the card and looked at it for a long moment.

“That’s kind of you to say,” Allison replied. “I don’t hold out a lot of hope, but there is one thing you could do for me.”

“Name it.”

“My sister had a diary,” Allison said. “It was very important to her. She had it with her at the camp, but when they sent her things home from her bunk, it wasn’t there. I know her things from that night are still in evidence. We’ve asked before if her diary was there—maybe it was in her bag. We’ve always been told it wasn’t. But it has to be somewhere. Could you look through the paperwork or boxes again? Maybe it was misplaced?”

“I’ve never seen anything in the files about a diary,” Sergeant Graves replied. “But I’m not about to pretend that things were handled well back then. I’ll go through everything and look for it. I’ll start tomorrow.”

“I would appreciate that,” Allison said. “It’s the one thing of hers I really, truly wish I had.”

“No problem. Good to meet you. Excuse me—I’m going to get something to drink.”

“I always ask about the diary,” Allison said when she was gone. “They always tell me they’ll look to shut me up. I guess they mean well. I don’t know.”

“I think it’s about time to do the honors,” Carson said to Allison, “if you’re ready.”

Allison nodded, and Carson got up and took his position behind the microphone. The DJ faded out the music, and Carson called out to the crowd to come gather around.

“Thank you for coming out tonight!” he said. “I’m Carson Buchwald, founder of Box Box. We’re here to dedicate the Sabrina Abbott Children’s Reading Room. And to do that, let’s have Allison Abbott come up. . . .”

Allison took the microphone and said some remarks about her sister, which got warm applause. Stevie scanned the tent. Most of the people there wouldn’t have been alive during the murders, or if they were, they had probably been children. It seemed a bit gross to use an occasion like this to gather people associated with the case in one place, but the truth was, it was also very effective.

Allison handed the mic back, and Stevie expected Carson to conclude the remarks, but things did not go that way.

“Now,” he said, “I’d like to tell you about something special I’m working on. Let me bring someone up here I want you to meet. Stevie? Can you come up here?”

“What?” Stevie whispered. “What’s he doing?”

“Stevie!” he said again.

Stevie put her taco back on the plate, wiped her hands on her shorts out of nervousness, and joined him.

“This is Stephanie—Stevie—Bell. You may have read about Stevie recently in connection with the events at Ellingham Academy in Vermont.”

The vast silence punctuated only by someone asking for a hot dog indicated that they either did not know or did not care.

“That case was famously cold until Stevie came along and helped to partially solve it . . .”

(Stevie had, in fact, entirely solved it, but that was not public. She ground her jaw.)

“. . . and I knew she was the person I had to partner with on my new venture. Obviously, you have a cold case here in Barlow Corners. Well, I want you to know, we’re here to make sure it doesn’t stay cold. Stevie and I have teamed up . . .”

Stevie saw Nate rub his hand all the way down his face, trying to block out what was happening. She felt her abdominal muscles tense and flex.

“. . . to make an investigative podcast, taking a fresh look at what happened here, and I’d like to get everyone in Barlow Corners involved . . .”

Total, muffled, deadly silence. Even the lightning bugs seemed to sense that this was a bad scene and flew out of the tent.

“. . . and together, we will get to the bottom of what happened at Camp Wonder Falls.”

He paused and looked around in a way that absolutely indicated that he expected some applause to follow.

It did not follow.

“So,” he went on, “we’re going to be here and working. If anyone wants to contact us at any time, you can reach me on Twitter, or Instagram, or you can message me on Signal. Everything you say will be completely confidential. So thanks, and please enjoy the evening!”

Stevie half wondered if he would blow a kiss and drop the mic. Instead, he gestured to the DJ, who deemed “Single Ladies” to be the correct jam for this particular car crash of a moment.

“Okay,” Carson said to Stevie, smiling. “I think that went great!”

Stevie wobbled a moment in bug-eyed horror, then tried to move back to the table, but Allison Abbot stepped forward, accidentally blocking her egress.

“What is this?” she said.

“A podcast,” Carson said eagerly. “Maybe a limited series. I’ve been talking to some producers—”

“This!” Allison said, gesturing around her.

Carson looked around the tent in confusion. “A picnic?”

“Is this some kind of publicity thing?”

“No, it’s to—”

“Buy our participation,” Allison said.

“No. No! See, I want to help. I want to—”

“You don’t want to help,” she said, her voice like a dull blade. “People always come here to write a book or make a TV show or a podcast or whatever. But you . . . you give us a room for children at the library, all as a way of buttering us up?”

Allison was directing all this at Carson, but Stevie was there, curling up inside, as the entire town of Barlow Corners turned to watch Allison remove the bones of Carson’s spinal cord one by one. The most charitable of the expressions showed embarrassment; most were cold and disgusted. Stevie felt herself getting a bit faint. She considered simply dropping to her knees and crawling away, under the picnic tables, out of the tent, across the green, into the woods, never to emerge. Nate and Janelle watched from maybe ten feet away, helpless. They may as well have been on the other side of a moat full of alligators.

“I’ll tell you what you can do,” Allison said. “You can take your picnic and your food trucks and your podcast, and you can shove it.”

“I really just want to dialogue. . . .”

Allison gripped the plastic tablecloth of a nearby picnic table, and Patty Horne hurried up to her.

“Let’s go,” she said to Allison. “Let’s get out of here.”

“I’m fine,” Allison said, her voice dry.

Allison lowered her gaze from Carson and looked at Stevie for a long moment. Stevie couldn’t read her expression, but whatever it meant, it propelled Stevie backward and away from Carson and out the side of the tent. She quick-walked across the green, not looking back. She could hear footsteps behind her, and Nate and Janelle caught up.

“Yiiiiikes,” Nate said. “Wow. Wow. Wow.”

“You okay?” Janelle asked.

“Fine. I just . . .”

“Yeah. We saw. Everyone saw.”

They stopped once they reached the statue of John Barlow. The base was large enough for all three of them to sit, and they could hide around the back. Looking at it up close, Stevie could see that it wasn’t a particularly good statue—it was slightly formless, a generic figure of a man on a generic rendering of a bored-looking horse.

“It’s ugly, isn’t it?” said a voice from behind them.

Patty Horne had left the tent and come to join them. She walked up, hands tucked in her jean pockets.

“I remember when they unveiled it,” she said. “They pulled off the cloth and everyone was quiet for a moment. My friends and I burst out laughing. And . . . don’t worry about Allison. She doesn’t mean it.”

“It definitely sounded like she meant it,” Nate replied.

“Well, she probably meant it for him, not for you. We get . . . tired’s not the word. . . . We get inflamed, I guess, when people come back and try to make something of the case. It’s like we heal and then the wound opens again. It was hard enough for me, but Allison lost her sister. It doesn’t matter that it was in 1978.”

“I’m not here to inflame, or . . . anything like that,” Stevie said.

“I know you’re not. You’re a kid.” The slight was inadvertent, Stevie felt, and she didn’t take it personally. “Some days it still feels unreal, like a story about someone else. Other times, like tonight actually, it feels like it just happened. I can remember so much about it—how it felt. It was warm like tonight. We would sit here on the green or go down to the Dairy Duchess for ice cream. I still go there sometimes and half expect to see Diane waiting tables.”

She seemed lost in thought for a moment, looking up at the strange metal head of John Barlow, then she snapped back to the moment.

“Want to come over to the bakery with me?” she asked. “Have some cake and relax while whatever’s going on over there blows over?”

She did not have to ask twice.

Fullepub

Fullepub