Chapter 19

Chapter 19

I should have foreseen that the happy bubble in which we floated through the end of June and into July was bound to burst. But the oracle cards, which I’d grown to rely on for daily guidance, did not warn me about the next visitor who would arrive at Ravenswood, or how her message would upend our lives.

Matthew had taken the twins to magic camp in the midst of a drenching summer downpour and was now back with Gwyneth and me in the barn.

“What on earth is wrong with the cards?” I said, trying to capture one of them that was flapping in midair. The rest of the deck was moving restlessly on the worktable, unable to settle into a legible pattern.

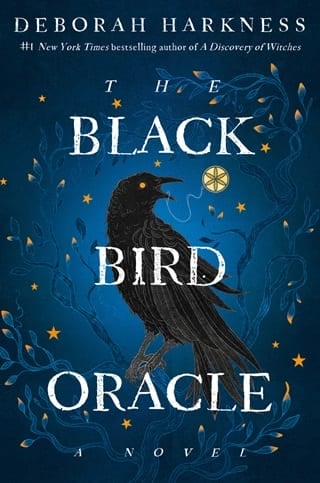

Gwyneth’s wards clanged as a stranger tried to pass beyond the witch’s tree. My heart skipped and I scrambled to gather the black bird oracle together and return it to its bag, away from curious eyes. Ardwinna’s ears pricked, and she rose to her feet, growling.

“Good girl,” Matthew told Ardwinna, stroking her head in reward before going to the door to see what had disturbed her peaceful sleep.

“No sane person is out and about in this weather.” The damp was hard on Gwyneth’s joints, and pain had darkened her mood. “By ash and bone, the winds have changed, and there’s an ominous portent in the air. Maybe that’s why the cards are misbehaving.”

Matthew opened the barn door, revealing a car that was stalled out on the top of the rise. We were together at the threshold to witness a small woman get out of the vehicle, its headlights still on and the wiper blades swishing this way and that. She looked like Mary Poppins, with a carpetbag clutched in one hand and a black umbrella in the other. A bedraggled waxed cotton coat with faded plaid lining was slung over her shoulders to keep out the worst of the rain.

“Janet.” Matthew was a blur, his feet digging into the slippery hillside so he could remain upright in the mud and the wind.

“It’s Matthew’s granddaughter. Something must be wrong.” I slipped the oracle cards into my pocket before removing an umbrella from the old pickle barrel by the door. I dashed into the rain after Matthew.

“Are you all right, Janet?” Matthew took the bag and loosened her grip on the umbrella’s bamboo handle. He held the serviceable black canopy over her, providing an elbow for support on the steep descent.

“Not really,” she replied, her rolling Scots accent thick and strong.

When I’d first met Janet Gowdie, she’d been living under the guise of a beneficent old lady. Today, Janet wore a disguising spell to appear like a woman in her early forties, even though she was born in 1841. She was dressed in a crocheted patchwork cardigan and jeans, with a pair of orange rubber clogs that suggested she was of an artistic temperament, not afraid of strong color, and liked thrifting at the local secondhand markets. That there was a formidably powerful witch inside the Bohemian outfit, with enough vampire blood in her to live for another two centuries, was not immediately evident.

With Matthew and I accompanying her, Ravenswood recognized Janet as family and relaxed its wards so that the three of us could pick our way down the muddy incline.

“It’s fine weather for ducks, but no good for other creatures.” My aunt ushered Janet inside the barn. “I’m Gwyneth Proctor. You look like you need a cup of tea.”

My aunt would not permit any further discussion until Janet was out of her sodden raincoat, into a pair of dry slippers, and ensconced in a rocking chair by the woodstove. Matthew hovered over his granddaughter’s shoulder, and Gwyneth eased her aching bones into a well-cushioned Windsor chair.

“Bless you, Gwyneth,” Janet said, taking a deep sip of the piping hot brew my aunt had provided. “Lapsang Souchong. Excellent choice. You don’t happen to have a dram of whisky? The last three days have been hellish.”

Matthew picked through the shelf of spirits in the alchemical laboratory. Gwyneth kept them handy for tinctures and to make the grounding spritzes she liberally applied to herself before family came to call. He poured a generous measure of a single malt from Islay into his granddaughter’s mug. The resulting brew must have tasted like a peat fire, but Janet seemed pleased.

Matthew, having confirmed that Janet was not bleeding, broken, or otherwise harmed, broached the subject of what brought her to Ravenswood.

“What’s happened?” Matthew asked gently.

“And how did you find us? Did Ysabeau tell you we were here?” I asked.

“I haven’t spoken to Granny. There’s been a clishmaclaver in Venice, and all hell’s broken loose.” Janet was a font of neglected treasures of Scots dialect. I had no idea what a clishmaclaver was, but Janet’s sour expression indicated it boded ill.

“You know about the Congregation’s message.” I sighed with relief. “You needn’t have come all this way to warn us, Janet. We already received it.”

“Not that clishmaclaver,” Janet said. “I’m talking about Meg Skelling.”

“Meg?” I frowned.

“She challenged Diana’s fitness for higher magic at the Crossroads,” Gwyneth said.

“So she informed us.” Janet drew a folded piece of paper from the pocket of her cardigan and smoothed it on her lap before donning her glasses and reading from its contents. “ Flashes of brilliant red and gold appeared all over Diana Bishop’s white flesh, with terrible vibrancy and awe-inspiring power. It would seem from Meg’s letter that Diana and her book were a bit rory that night.”

All of my line have a certain glaem about them. So what? Granny Dorcas apparated into the empty rocking chair beside Janet, her brow bristling and her elf lock trembling. Her sudden presence would have unsettled most creatures, but not Janet.

“There you are. I thought I smelled a wee ghostie.” Janet clucked with sympathy. “The fae are keeping company with you, I see. How dreadful. You must be covered in bites.”

Granny Dorcas scrutinized Janet head to toe.

And you’re like the babes, ’twixt and ’tween. Granny Dorcas gave Janet a sniff. More human than they are, though. Less powerful, too.

“Right on both counts,” Janet said mildly. “I’m Matthew’s granddaughter, though at three generations removed.”

“This is Granny Dorcas,” I said, making the introductions. I tried to calculate our relationship on my fingers. “Ten—no eleven generations—removed.”

Gowdie, you say? Mumbling, Granny Dorcas went to the woodstove. She fished about in the flames with her bare hands, searching for an ember to light her pipe.

“The Congregation is aware that Diana has the Book of Life within her. Why is this an issue now?” Matthew asked.

Based on the knowing flicker in Gwyneth’s eyes, she knew about the Book of Life, too. Gossip traveled quickly in witch communities, and news of my earlier discovery had apparently made its way from Venice to Ipswich.

“It’s an issue because Margaret Skelling claims that Diana learned the secrets of bloodcraft from its pages,” Janet said bluntly.

“The lost branch of higher magic?” Gwyneth frowned. “Diana knows nothing of that. No witch does.”

“All appearances to the contrary.” Janet’s eyes sparkled with fury. “Let’s see. What did Meg say?… Flashes of brilliant red and gold… No, I’ve read that bit. Ah, illuminating the word BLOODCRAFT. The wee besom put it in capitals, so we could find it easily amidst the rest of her screed.”

Our secret was out. Until now, Matthew and I had kept quiet about the fact the Book of Life mentioned bloodcraft in connection with mixed-race children born to blood-rage vampires and weaving witches, though others had suspected as much—Gerbert D’Aurillac, Peter Knox, and Matthew’s son Benjamin chief among them.

“And to think I let you into the Crossroads with this secret inside you!” Gwyneth cried. “No wonder Meg let you find your way in the wood. Your secrets were an open book to her!”

“And she was reading it closely,” Janet said. “Though, to be fair, bloodcraft would be impossible for any witch to miss. According to Meg, the word appeared in the middle of Diana’s forehead, sealed with a witchscore.”

Granny Dorcas was at my elbow. She drew her fingers through the space between my brows, first in one direction, then the other, passing over my witch’s third eye. My skin tingled at her touch, and for a moment I was reminded of the white pattern of feathers on Cailleach’s face.

The mark of the Crossroads, Dorcas said, her voice hollow, left behind when a witch casts a maleficio and takes her sister’s power.

“But Meg didn’t take my power,” I said, confused. “Only Mom and Dad did, when they spellbound me. Not even Satu J?rvinen succeeded in robbing me of it—though she certainly tried.”

“Stephen didn’t spellbind you, my dear.” Gwyneth reached for my hand. “Your father didn’t have the training or the skill to work such a complicated piece of higher magic. Only an adept like Rebecca would have the necessary knowledge.”

“That can’t be true,” I said. “I spellbound Satu.”

“Then she wasn’t spellbound for long,” Gwyneth pronounced.

“Do all the Congregation witches know higher magic?” A ball of lead formed in my stomach. Satu was a weaver, like me. Unless…

“They’re all adepts,” Gwyneth replied, “and all graduates of the Congregation’s higher magic track. Only the most powerful witches are selected to play a role on the ruling council.”

The lead ball in my belly grew. I buried my head in my hands and swore. My ignorance of higher magic had caused me to make a terrible mistake—one that could have damaging consequences for me and my family.

“Satu was a member of the Congregation when she left the witchscore on my forehead. She’s a weaver, like me,” I explained. “I have no idea what kind of maleficio she cast.”

Gwyneth swore, too, and Granny Dorcas and Janet joined in. I couldn’t bear to look at Matthew. What a mess we’d made.

A shrill scream and a barrage of whispers erupted from Granny Dorcas’s tangled lock of hair. She sat bolt upright.

I remember you now, Mistress Gowdie! Smoke streamed out of Granny Dorcas’s mouth and nose, and orange sparks escaped from her pipe. ’Twas you who visited us that night in the gaol. But you didn’t take my memories on May Eve. Give Bridget’s memories back to Diana, witch, or I’ll hex you bald, blind, and blue.

“It wasn’t me you saw in Salem, Goody Hoare.” Janet held up her hands in a gesture of appeasement. “You met my mam, Griselda Gowdie. I’ve come to find her memories of that night.”

“Your mother’s memories?” I was dumbfounded. “What about Meg and the Congregation?”

“Nothing is ever simple in this family.” Janet pulled another folded paper from the other pocket of her cardigan and handed it to Matthew. The goddess knew what else she had stashed in there. “You both need to read this.”

Matthew scanned the worn page. “It’s a letter from Grissel Gowdie to her mother, sent from Salem on May Eve 1692 to Agnes Gray of Elgin.”

May Eve. Walpurgisnacht. The night when people lit bonfires to burn witches—or their effigies. My blood thickened with fear at the memories of riding through the flames to flee Rudolf’s court.

“Granny Janet was living in the caves of Covesea then,” Janet explained. “My mam, Griselda, was born there. She didn’t see the sun for the first five years of her life, only the reflected light from the water and the glow of the moon when Granny Janet let her run free at night. They spent the days weaving spells and telling old stories, and the wee hours hunting for treasures and food.”

“She alludes to that in the letter,” Matthew said. “ Blessed mother, I arrived in the colony of Massachusetts on the 13th day of April, as foretold by the winds’ whispers on the day I was born and the tales Granny Isobel and Granny Janet wove around the fairy pool. You can rest now in the knowledge that the oath you swore has been fulfilled.

“ They have charged many of our kind and imprisoned them in a foul underground gaol in a town called Salem. There they await trial, along with many innocents who know nothing of our ways. One is a wee bairn not yet seven ”—Matthew’s voice hitched on the child’s age—“ who is shackled beyond the reach of her captive mother. Both are mad because of it, unable to give and receive comfort. ”

Mercy. Mercy. Granny Dorcas keened and swayed, tearing at her elf lock. Mercy is gone.

I soothed my grandmother’s cries as best I could, but she was inconsolable. Matthew continued with Grissel’s letter.

“ Our dam’s yarnings are proven true daily, and at last I see a pattern in the goddess’s weaving. ” Matthew’s voice had the quiet solemnity of a prayer. “ It is just as the silvered one told Granny Isobel, who knotted the knowledge of it in the wind. The one who will be first to hang was brought to this place on the 18th of April. She is not surprised, nor her friends, nor even an unexpected summer traveler who has come here for some purpose of his own. ”

Matthew drew a deep breath before proceeding.

“ The silvered one did not reveal everything to Granny Isobel, however. I must leave what I have learned behind for fear that it will come into evil hands, ” Matthew read. “ Until then I give you the words from another oracle: ‘For we know in part, and we prophesy in part.’? ”

It was a passage from the Bible—a clever way to encode a message that would be acceptable to any Puritan official who might come by it. I suspected Grissel had done so again in her references to the silvered one— a traditional name for the goddess—and the mysterious summer traveler.

“ I do not know if the winds blow with or against my return, but I will seek to get this letter to you by whatever means I may, ” Matthew said, drawing to a close. “ Until then, keep time by the moon and the stars and remain close to the earth from which we all come and to which we will all return. Written from Salem on May Eve in the year 1692, by the hand of your devoted daughter, Griselda. ”

Matthew turned the letter over.

“ To Agnes Gray in Elgin via the captain of the Golden Serpent, Portsmouth. ” Matthew’s mouth tightened. “I knew it.”

I took the letter from Matthew. There was the address, just as Matthew said. In the upper right corner, where the stamp would have been on a modern letter, I saw a faint symbol.

“Jupiter,” Matthew said. “My father’s cipher.”

“Did Philippe have eyes on the Salem panic?” I asked numbly. Like the Golden Hind, the Golden Serpent could only have belonged to one man. “Was the captain of Philippe’s ship Grissel’s summer traveler?”

“That’s what I wondered—and why I’m looking for the memories Grissel left behind,” Janet said. “The goddess only knows where she would have put them for safekeeping.”

“Gwyneth and I used a memory bottle as a lure to catch the ghosts.” I jumped to my feet. “Maybe Griselda’s memories are stashed in one of the trunks in the attic.”

“Have you reached the subject of mnemonics, Gwyneth?” Janet asked.

“The arts of memory?” I’d learned something about them in graduate school from a medievalist obsessed with Ramon Llull. And Janet was right: The subject hadn’t been on Gwyneth’s summer syllabus.

“The craft of memory.” Gwyneth pushed her spectacles up to the bridge of her nose. “It’s the branch of higher magic that preserves our history for future generations. Rebecca was a particularly skilled mnemonist before she stopped practicing higher magic. And no, Janet, our lessons haven’t touched on that part of the curriculum.”

Poor Bridget’s secrets. Granny Dorcas wiped her eyes. She shared them with the Gowdie witch, but they belong to you, Diana.

“Only initiates and adepts are authorized to extract memories, as well as store, release, and maintain them,” Janet added. “There’s a great demand for the service these days—far greater than for love magic or protection spells.”

“I’ve never heard of such a thing, and I don’t think Sarah knows anything about mnemonics, either,” I said.

“We all know about them,” Janet replied, dismissing my claim. “Every family has one or two bottles knocking around in the back of a cupboard or tucked in a box with the Hummel figurines and souvenir teaspoons. The problem is that unless you look after them, the wax seals break, the memories escape, and people think their house is haunted. Sometimes the bottles get left behind for rubbish when a house is sold. It’s a nightmare for new owners.”

“If Grissel’s memories of Bridget aren’t here, then there’s only one other place they can be,” I said.

“The Bishop House,” Matthew said, nodding in agreement.

“I’ve always wondered why the house insisted on going with them when they left Essex County after Bridget’s hanging,” I said. The rest of the house had been built around the old saltbox, which now served as Sarah’s stillroom. “Maybe it’s been holding on to Grissel’s bottles for safekeeping,” I said.

“I’m going to Madison to find out,” Janet said with grim resolve.

“I’m coming with you,” I replied.

“So am I.” Gwyneth’s expression was dark with satisfaction. “I think it’s time Sarah Bishop and I buried the wand.”

—

It was midafternoon the next day and a busy drone of insects, farm equipment, and lawn mowers provided a steady soundtrack as we turned off Route 20 and onto the lane that led to the Bishop House. I spotted it in the distance, its clapboard siding recently painted, the mailbox still atilt, and both the American flag and the progress flag fluttering in the wind. A coexist banner hung from the fence, too. Sarah must have run out of room for activist messages on her car.

The temperature reading on the bank’s illuminated sign in Madison registered nearly ninety degrees, the heat clinging like honey. Ipswich’s summer storms would have been welcome here in upstate New York. The only escape from the oppressive atmosphere would be in the movie theater in Oneida or the air-conditioned grocery store in Hamilton. The Bishop House would be purgatorial, even with every window in the house flung open.

All three of us were on edge, which had made small talk difficult on our journey west from Ipswich. Gwyneth found a classical music station, which should have soothed my raw nerves but didn’t. Janet sat in the back seat and knitted, her needles clacking in time to the music, occasionally asking a question about the small towns we were passing through and the covens that were based there. I worried about my reunion with Sarah. She’d been texting me recently to see how we were getting on at the Old Lodge, and I hadn’t replied. She may have started worrying that something was wrong.

“Not a decent ward anywhere,” Gwyneth said disapprovingly as we proceeded up the drive. It wasn’t pitted anymore—Matthew had seen to it that the surface was solid enough to support the weight of the Range Rover—but it was devoid of any type of protection, magical or human.

Wait until Gwyneth discovered that the front door didn’t have a lock and the back door was on a latchstring.

“Sarah doesn’t believe in wards,” I replied, continuing with our slow progress. “She thinks they make humans uncomfortable and are bad for business.”

Be Blessed, Sarah’s organic foods and magical supplies shop, was similarly unprotected except for a bell on the back door that let out a gentle chime when someone opened it, and a sign in the front window that read guard cat on duty .

“Once we get inside, let me deal with my aunt,” I said, turning toward Gwyneth. “She’s my problem, not yours.”

“Is she?” Gwyneth raised her brows. “Sarah has been a thorn in my side since before you were born. I should have settled things between us long ago.”

“Ouch!” I cried as a sharp barb pricked into my flesh. “Gwyneth, could you reach into my pocket and take out the oracle cards? If they keep sticking their corners into me, they’ll draw blood.”

Gwyneth dipped into the cargo pocket on my favorite summer wear and pulled out the bag. It squirmed and wriggled like a colicky baby. She put the troublesome cards in the cupholder.

“Still fretful, I see,” Gwyneth said with a sigh. “I know just how the black bird oracle feels.”

I pulled up in front of the house and turned off the ignition. Janet was quick to spring out of the vehicle and help Gwyneth from the front passenger seat. I remained where I was and sent a text to Matthew to let him know we had arrived safely. Then, I gathered my resources. If we were lucky enough to find Grissel Gowdie’s memory bottle, it was bound to be explosive.

I had settled my nerves and was ready to exit the car when my aunt burst out of the house wearing her favorite turquoise-and-gold kimono. Her hair was barely contained in a scarf, and she was wearing a pair of furry slippers that made her look like Bigfoot.

“Why aren’t you dead yet, Gwyneth?” Sarah demanded.

All my resolutions to keep calm and carry on evaporated in a wave of outrage.

“You always were a touch feral, Sarah,” Gwyneth observed calmly, looking down her nose at my aunt.

Sarah flung two cards at her. “Stop sending your damned birds. I’ve got plenty of tarot cards, thank you very much. Next time one of your ravens comes around here, I’m going to shoot it.”

The black bird oracle, bag and all, propelled itself out of the cupholder and plastered itself against the window.

No wonder the cards had been so agitated and fretful. One of the family’s ravens had absconded with two cards and carried them to Madison to prepare Sarah for our arrival.

“Janet. Hi,” Sarah said, finally registering the presence of Matthew’s grandchild. “You’re welcome to come in, of course, but not her.”

“ Och, I think you’ll find we’re an inseparable trio, Sarah dear,” Janet said, returning to the back seat to pull out her knitting bag.

“Trio?” Sarah said, peering through the car’s tinted privacy glass.

“Hello, Sarah.” I climbed out of the car. Things were off to a spectacularly bad start. I spotted The Bottle and The Owl Queen lying in the grime of the driveway. “Please don’t throw my cards on the ground. They don’t like it. Neither doI.”

I held out my hand and the missing cards flew into my palm.

Sarah stared at me in astonishment. “Diana! You’re supposed to be in England!”

“Gwyneth’s not dead and I’m not at the Old Lodge,” I replied crisply, slinging my bag over my shoulder. “As for the ravens, you weren’t the only member of the family to receive a visit from them this summer. Becca did, too. My important messages came through the regular mail: one from the Congregation, and one from Gwyneth.”

Sarah’s eyes shifted to Janet then back tome.

“Because I have both a maternal and paternal history of higher magic, Sidonie informed me that they wouldn’t wait until the twins turn seven to examine them,” I said, recapturing my aunt’s attention. “Janet came to warn me that the Congregation wants to know not only the twins’ secrets but also the knowledge of bloodcraft that is written in the Book of Life. She wants her mother’s memory bottle back, too.”

“Memory bottle?” Sarah’s voice was hushed. “How do you know about—”

“How do I know?” I demanded. “The same way that I know about the Proctors and the Dark Path. Gwyneth invited me to Ravenswood and I went. How could you keep me from my own family?”

“I made sure that Rebecca and Stephen’s wishes were followed—that’s all,” Sarah replied, her voice rising.

“You sound so certain,” Gwyneth said bitterly.

“I am!” Sarah snapped. “Stephen told me what they’d decided. He said—”

“I can imagine what Stephen said.” Gwyneth’s voice was steely. “But I find it hard to believe that Rebecca agreed with him. It’s even harder for me to fathom why you were so quick to accept his word for it. You’re clever, Sarah, like most Bishop women. You fell for Stephen’s line completely.”

“Stephen wanted nothing to do with you,” Sarah insisted. “As for Diana, they both wanted her to be a Bishop.”

“Well, she’s a Proctor now,” Gwyneth said. “Higher magic and all.”

“Darker magic nearly killed Rebecca. It did kill Emily.” Pain doubled the anger in my aunt’s voice. “How many witches need to die before you people stop dabbling in forces beyond your control? If something happens to Diana or the children, I’m holding you responsible, Gwyneth!”

“I chose my own path, Sarah,” I retorted. “It’s my legacy, and my birthright.”

“It is not.” Sarah’s face was the color of a rose hip.

“It is. Mom was one of the Congregation’s talented adepts,” I said. “But you already know that.”

Sarah looked flustered. “The Bishops haven’t approved of higher magic for a long time.”

“Well, Mom got her talents from somebody!” I exclaimed. “She didn’t summon them out of thin air one October morning. Who was it? Grandma? Or someone farther back in the family tree?”

A shadow flitted through Sarah’s brown eyes. It was soon replaced by her usual stubborn glint. Silent, my aunt pursed her lips and crossed her arms.

“Typical.” I entered the house, letting the screen door slam behindme.

“Every witch thinks they can practice higher magic without consequences,” Sarah said, following me inside. “Emily and Rebecca learned the truth and turned their back on it.”

“They did not.” Of this, I was sure. I’d seen my mother scrying, and Emily had died trying to reach my mother’s spirit for guidance. “Mom and Em knew you disapproved of the higher branch of the craft, so they hid it from you. Just like Mom hid it from Dad.”

Janet and Gwyneth were still outside. “Why are you both standing there?” I called, exasperated.

“The house has taken the doorknob, Diana dear,” Janet said apologetically.

“This place is very badly behaved,” Gwyneth said, surveying the ceiling of the porch as though it were infested with wasp nests. “The Proctors would never put up with this kind of nonsense.”

I let my aunt and Janet in and shouted into the heating vent. “Granny Bridget! Grandma! I want to talk to you!”

The keeping room doors sprang open. Two ghosts, startled from their sleep, looked at me bleary-eyed. Their transparent green outlines were startling after the substantial specters who haunted Ravenswood.

There’s no need to shout, my grandmother, Joanna Bishop, said. We’re sitting right here.

And have been since yesterday, Granny Bridget added. When Dorcas’s ravens came, I knew you would be here soon.

Gwyneth spotted the ghosts. She turned on Sarah, angrier than I’d ever seen her.

“This is an outrage,” Gwyneth said. “Those ghosts should be locked up. Look, Janet. They’re utterly drained of spirit. I should report you to the Congregation for mistreating your elders, Sarah Bishop. Your neglect has reduced them to smudges!”

“You can’t come into my house and order me around, Gwyneth,” Sarah fumed, sparks flying from her curls in a rare display of temper. She clomped across the front hall, her Birkenstocks tapping out a drumroll of warning. “Get out! You aren’t welcome here.”

“There, there, Sarah,” Janet said, trying to defuse the situation. “To be fair, Bridget and Joanna are in a ragged state.”

The argument over the care and feeding of ghosts raged on, but I had eyes and ears only for my Bishop ancestors. Gwyneth was right—my grandmother and Bridget were so weak they wouldn’t withstand much questioning. I had to choose my words carefully.

Were you canny at the Crossroads, daughter? Bridget wondered, venturing a question of her own.

“I’m not sure,” I confessed, knowing better than to lie to such a witch. “You were right, though, about the secrets buried there.”

There are more, Bridget said, toying with the laces on her bodice.

Don’t worry, Bridget. Grandma was addressing my ancestor, but she was looking at me. Diana has been walking the Dark Path since she was born. Rebecca and I spoke of it whenever we worked together in the stillroom.

The stillroom was now Sarah’s domain, and a place I associated with failure and loneliness. But the room had felt more welcoming to me after Matthew and I returned from our timewalk. It’s where Sarah had revealed a cupboard that held my mother’s enchanted clock radio that played nothing but Fleetwood Mac and a chunk of her dragon’s blood resin. There was nothing else in it except—

Empty, dusty jars and bottles.

“Thank you, Grandma,” I said. She’d anticipated my question and given me the clue to its answer before I could askit.

I made a beeline for the back of the house.

“Where are you going?” Sarah said.

“I told you. We’re here to look for something that belongs to Janet,” I said. “Once I have it, we’ll be on our way.”

Sarah flapped after me, her kimono sleeves billowing.

I marched through the kitchen and stepped into the cool, dim depths of the old stillroom. Originally used as a summer kitchen, it still retained the wide hearth, the ovens, and the storage loft where flours and grains had been kept over the long, snowy winters. The cupboard that held Mom’s radio and resin had been built into the stonework to the left of the old fireplace.

It was no longer there. I swore. The house was always rearranging things to suit its own arcane purposes.

In the corner, I spied a thin strand of amber tangled with a knot of blue. The warp and weft of time trapped things long forgotten in small spaces like this.

Hoping that the amber and blue threads might lead me to the cupboard’s current location, I carefully inserted my index finger into the center of the knot. It tightened around my recollection of the old storage place, and around my finger, too.

An arc of blue spun across the room. I followed its path as it moved toward the stillroom fireplace. But it stopped before it reached the sooty brick. The end danced around the massive butcher block island and hit the doorframe.

The missing cupboard now blocked the passage to the kitchen.

I flung open its doors. My mother’s scent—lily of the valley—escaped into the room, along with the now familiar aroma of petrichor and brimstone that I associated with higher magic.

The bottles were just as I remembered them: grimy jars with lids, some containing bits of dried roots and herbs, some large and some small. One bottle was encased in raffia and candle wax. Another had the distinctive shape of a bottle of Mateus. Behind them were older bottles with wax seals, and other glass and pottery containers. As for Mom’s old clock radio, it was nowhere to be seen.

“What’s in front of the door?” Sarah demanded. She tried to wedge her zaftig body through the slender gap.

“Step aside, Sarah. Let me give it a go.” Janet used her vestigial traces of vampire strength to shimmy the edge of the cupboard so that Sarah and Gwyneth could pass through. The three witches joined me in front of the open cupboard.

“Look, Gwyneth. There are dozens of memory bottles here,” I said in disbelief. “Who do they all belong to?”

With great care, I reached for one of the bottles. It was seemingly devoid of contents and had faceted sides like a condiment jar. There was a faded cocktail sauce label, and it was stoppered with a cork sealed tight with thick globs of dark wax. As soon as I had it in my hands, I knew it contained memories. It was heavy—far too heavy for its size, just like the bottled autumn happiness that we’d used to attract the ghosts.

I grabbed a cardboard box from the floor. It had held a case of Spanish wine—a gift from Fernando no doubt. It would be the perfect way for me to transport the memory bottles safely out of the Bishop House and back to Ravenswood, where we could examine them more closely. I used the cardboard dividers to hold the bottles securely, wedging several of them into each of the twelve compartments so that they wouldn’t clink together and crack.

“You can’t take those. They’re not yours.” Sarah grabbed for the same bottle I was lifting from the shelf. It had originally held mustard or maybe strawberry jam. Now it was empty, except for a few brown seeds.

“Mom left these memories for me—just like she left the radio.” I closed my fingers around the jar and held tight, jerking my arm back to pull it out of Sarah’s grasp.

The point of my elbow knocked painfully against the open door of the old cupboard, sending shock waves through my arm. Another bottle teetered precariously on the edge of the shelf.

Gwyneth rushed forward to catch it, but she was too late. It smashed against the floor. In our astonishment, Sarah and I let go of the other bottle. It, too, broke into a dozen pieces at our feet.

Glossy squares of cardboard rained down from the roof of the stillroom, brightly colored and sparkling with magic. They were too large to be oracle cards.

But I had no time to determine what the flying objects were, or their significance. The memories that had been released from the bottles were overtaking me, only this time there was not one series of recollections but two, a chaotic blend of sounds, feelings, and impressions.

It was then that I learned that some of the memories were mine.

Fullepub

Fullepub