Chapter Nine

Angelique laughed. "Look at us! We're like a cuckoo clock this morning."

Angelique was right: the four of them—Delilah and Tristan and Angelique and Lucien—had popped from their rooms at almost precisely

the same moment, indeed like a cuckoo on a clock. They were up even earlier than the maids this morning, in part because Lucien

and Tristan needed to inspect a new warehouse the Triton Group, their shipping partnership, hoped to lease.

While everyone was still singing about the pianoforte last night, Lucien and Tristan and Mr. Delacorte had lingered over papers

and numbers regarding the Triton Group in the smoking room. Their wives had already been asleep by the time they'd gone up

to their bedrooms.

"This will be the first time I've beaten Delacorte to breakfast, I reckon," Captain Hardy said.

They had all taken a few steps down the hall when Delilah stopped and laid her hand on Tristan's arm to stop him, too. "Do

you all hear that? It sounds like... someone weeping."

They paused to listen.

The sound was faint but unmistakable... and chilling: a low, mournful keen that seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere.

The little hairs lifted on Delilah's arms.

Angelique swallowed. "Surely it's the wind. Though I thought we did manage to find and repair all the drafts after the last

storm."

"Maybe we've just never been up early enough to hear the ghosts before." Lucien was whispering for some reason.

"Shhh." Angelique squeezed his arm.

The sound seemed to increase in volume as they moved down the hall.

... ohhhhh ...

It had acquired a distinct note of anguish.

"Christ," Lucien breathed. Unnerved now.

"Where is it coming from?" Angelique's head tipped back toward the ceiling, as if this was the province of ghosts.

Captain Hardy gestured them forward, as if they were a landing party confronting a hostile army. As a group, they tentatively

descended a few stairs.

Then stopped again to listen.

Seconds later they heard:

... oohhhh ... OHHHHH...

Much louder now. And... hoarser.

"It's definitely someone in pain," Captain Hardy said grimly. "And it's a woman. I think she's saying ‘no'?"

"Tristan!" Delilah gasped.

Tristan and Lucien swiftly produced pistols from somewhere on their persons—neither Delilah nor Angelique asked questions anymore—just as a hoarse scream froze the blood in their veins.

... Ahhh Ahhhh AaaaAAAUUGG GGGH Simon!

En masse, they hurtled down the stairs.

The echoes of that scream were dying behind the door of Corporal Dawson's room.

"Oh God oh God oh God," Delilah fervently prayed.

"Stand back!" Captain Hardy hoisted a leg to kick the door down.

"Wait!" Lucien seized Captain Hardy's shoulder. "Listen."

Then they recognized it: A sound reminiscent of a goat kicking the slats of its stall.

A rhythm as old as time.

In other words: the legs of a bed against a wooden floor.

Thump. Thump. Thump. Thump. Thump.

Thumpthumpthumpthump thumpthumpthumpTHUMP !

The last mighty thump had them scrambling backward as if the door were about to explode.

Too late, Delilah crossed her arms over her head in a futile attempt to prevent Corporal Dawson's gurgling cry of ecstasy

from entering her ears.

And then all was blessed silence.

As this was not an experience any of them had ever anticipated or hoped to share with one another, no one knew quite where to aim their eyes, or what to do with their hands. Tristan and Lucien were still holding pistols. They were all in fact crouched a little, as if the ceiling was caving in.

"Holy Mother of God," Lucien finally breathed, in awe.

He spoke for all of them.

They were all silent, winded from being buffeted between terror, mortification, relief, and maybe just a little envy, in a

matter of seconds.

It was all cooing and murmurs behind the door now. And giggles.

"I say we shoot them anyway," Captain Hardy suggested darkly.

They stifled uneasy laughter.

This little tableau—the drawn pistols, the stupefied expressions, the cringing postures, as if they wished they could all

change out of their old skins into new, unsullied skins—was what greeted Mrs. Pariseau when she exited the room adjacent,

handsomely dressed in a maroon day dress.

They all gave a guilty start.

"Well, good morning, everyone." She turned the key in her lock.

"Good morning, Mrs. Pariseau," they replied in absurd unison.

She paused to study them, amused.

She gestured with a head tilt at Corporal and Mrs. Field Mouse's door and whispered, with an eyebrow wag, "Third time today!"

They stepped aside so she could pass down the stairs.

One of the things Delilah and Angelique loved about being proprietresses of a boardinghouse near the docks was the variety. And while the day-to-day was on the whole delightful, they had also contended with the British soldiers pouring into the building, a runaway French princess, a secret tunnel, smugglers, ravenous German musicians, a scandalous opera singer, several attempts by various aristocrats to steal their cook, a makeshift gambling den, financial fluctuations, Mr. Delacorte, and Dot. They had managed all of this more or less with aplomb.

Somehow confronting this newest challenge seemed to require more courage than all of those combined.

As the comfort of their guests was paramount, they intercepted Mrs. Pariseau in the foyer when she returned from her morning

jaunt and invited her for a cup of tea in the kitchen.

The three of them sat at one end of their large worktable while Helga rolled dough for tarts at the other end.

"Mrs. Pariseau, we're so terribly sorry about the... the neighborly disruption. Would you like us to move them to another

room? Would you like us to prepare another room for you temporarily?"

Mrs. Pariseau lifted a hand. "Oh, please don't trouble yourselves, ladies. I can pretend it's the sound of wild animals murdering each other on the savanna or some such. It's an inexpensive way to go on an educational little holiday in my mind. Last night I imagined it was a hyena tak ing down an antelope. I went to a lecture about those animals not too long ago, as you may recall. So interesting. And Corporal Dawson is only on leave for a fortnight, after all."

They were currently about five days into this fortnight.

"And, well, we're all only young once." Mrs. Pariseau shrugged one shoulder. "I can sleep whenever I like these days."

An awkward little silence ensued. Both Angelique and Delilah were just over thirty years old. Neither one of them was inclined

to volunteer that their own youthful experiences had been significantly less abandoned.

"That's quite generous-spirited of you, Mrs. Pariseau," Angelique finally said. "But good heavens... that is... they're

at it both day and night?" She lowered her voice to a hush, even though the maids were off performing their duties. She tried

to keep that frisson of envy out of her tone.

"Whenever you don't see them in the sitting room, and they haven't gone out the front door, assume they're mounting each other,"

Mrs. Pariseau confirmed.

Delilah's shoulders flew up to her ears in a scrunch at the word "mounting."

"And you know... it's the same sequence of noises every time. It's absolutely fascinating," Mrs. Pariseau mused. "Like

a mating call. Many animals have a unique one they use to attract a mate, were you aware?"

There was a silence, as Delilah, Angelique, and Helga all marveled at the store of arcane and occasionally uncomfortable knowledge that Mrs. Pariseau seemed to possess. As a relatively monied widow, she was able to liberally indulge her passion for learning.

They fervently hoped Mrs. Pariseau wouldn't be inspired to ask "If you had a mating call, what would it be?" in the sitting

room.

"Funny thing, however. They were in residence for a few days before it started up," Mrs. Pariseau added.

They all reflected on this.

"Maybe Corporal Dawson finally found... er, her, you know... ah, it ," Helga whispered.

Delilah nearly choked on her tea.

When Dot entered the kitchen seconds later, she found them all scarlet-faced and muffling snorting laughter in their palms.

"What did Corporal Dawson finally find?" Dot asked.

"Love," Delilah said firmly at once, wiping tears from her eyes. "Isn't it lovely that he's found love with Mrs. Dawson?"

"I suppose it must be," Dot allowed, somewhat wistfully.

Alexandra could scarcely even hear the cobblestones pass beneath them, so well-sprung, sturdy, and smooth was the carriage. Outside the window, the London streets unfurled as the four matched bays and the skillful driver took them to the first of the events during which they would attempt to convincingly portray a devoted married couple, the Earl and Countess of Chisholm's ball.

Magnus had been out all day, but he'd returned to The Grand Palace on the Thames in time for the cheery ruckus that was dinner.

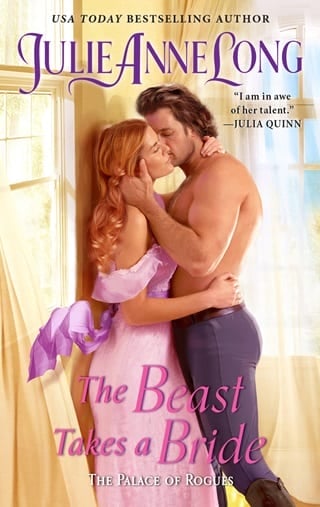

"You hardly look like a feral beast at all," was what he'd said when she'd emerged from her room wearing the rose-colored

silk about a half hour earlier.

But his pupils had flared to the size of farthings. At least four heartbeats' worth of utter silence had elapsed before he'd

gotten the words out.

She'd almost forgotten the piercing rush of delight that came from experiencing herself as beautiful in a man's eyes.

Nothing apart from that stillness and pupil flare, however, seemed to interrupt his usual cast-iron composure.

"Thank you, Magnus. No one would mistake you for a beast, either. We're already winning, I think."

This exchange had mordantly amused Alexandra. What were the rules when it came to estranged spouses offering each other compliments?

They were very careful not to tread over some tacitly understood line of effusiveness.

Whoever was tasked with dressing him understood how to tailor for his body. The fit of his black coat lovingly emphasized his imposing frame and tapered from his vast shoulders to his hips. His shave was fresh and his tawny hair was brushed back off his forehead and some of it was tucked behind his ears. His crisply trimmed side whiskers emphasized his strong jaw and hard, high cheekbones. Silver buttons glinted on his dove-gray waistcoat.

He looked stern and polished and regal and, if she was being honest, scary, in an intriguing way. It made her feel strangely

a bit shy. As if this dashing man in this dimly lit carriage was yet another version of Magnus she hadn't yet met.

He took up most of the carriage seat opposite; he seemed to create his own atmosphere, like incoming weather.

He gazed across at her thoughtfully.

And unswervingly.

Rather the way one would keep something lethal or something miraculous in one's sights. A dragon, or a holy grail, she thought.

A warmth akin to a low and not unpleasant fever again flushed her skin. As if she had been set aglow by the fixed quality

of his attention.

It was impossible to know what he was thinking. It seemed rude to look away. Moreover, she didn't want to, not at all, and

this was what finally made her force herself to turn her head to gaze out the window.

She had spent most of her day making lists of the additional things she wished to bring with her to New York. The packet ship she would take from Liverpool required two copies of the list of the possessions each of the twenty-eight or so passengers were bringing on their journeys, and she needed to redo the chore in light of the fact that she would not be returning to England. So she fought back resentment and a thousand other conflicting feelings, and did it.

Rummaging through her head for things she could not live without gave her a reason to reminisce, and then she became reflective.

She would be bringing a little more than she'd originally planned, of course, but far less than she'd anticipated. It was

a revelation to discover what she truly valued: a few little mementos from her childhood, a miniature of her mother, her art

supplies. And to find that even as her heart felt somewhat heavy at the reason for doing it, as though she were sorting through

a dead loved one's possessions, she gradually began to feel oddly lighter. And to even dare to begin to look forward to a

new life, given how thoroughly she had inadvertently botched the one she had.

"This carriage is new, isn't it? It's very beautiful." She aimed her words out the window. They were nearly to St. James Square.

"Yes, I commissioned it last year. For now, I keep it in a livery nearby. Eventually I will keep it in the mews of a town

house on Grosvenor Square I'm in the process of purchasing."

Her heart jolted. She turned to him. "You're purchasing a home on Grosvenor Square?"

"Yes," he told her quietly. "I thought a new home would be the best way to make a fresh start. It's why I'm selling the town

house."

She nearly swallowed, but she was afraid he might notice. Her eyes burned.

"Of course," she said politely, finally. "I hope it's all you want it to be."

The footman's announcement—"Colonel and Mrs. Magnus Brightwall"—was greeted by the swirl of bright dresses and flash of tiaras

and jewels in the chandelier glow as everyone turned toward them.

Magnus was about as physically conspicuous as a man could be and a notable personage on the threshold of becoming even more

notable. And Alexandra was somewhat new to the people of the ton, who were accustomed to seeing the same people over and over

at all their balls and parties.

And she was beautiful. Beauty conferred a different sort of royalty on a woman.

The dramatic contrast between them essentially ensured that all eyes would be glued to them.

Magnus had known they would be.

He was accustomed to negotiating crowds and to the feel of hundreds of eyes upon him. But he'd never entered a room with a

woman like Alexandra on his arm.

Her gown was the same shade as her lips and her blushes, and, he could not help surmising, her nipples. It was overlaid with

a sort of gossamer net dusted with tiny gold flowers, and her skin and coppery hair were luminous.

She stunned, in every sense of that word. His senses were consumed with the fact of her. He was quietly furious that he'd briefly lost his ability to speak when she'd stepped out of her room this evening. As surely as if he'd been physically smote.

But he had grown adept at metaphorically locking inconvenient feelings away into little cells, as if they were criminals who

oughtn't mix with the civilized population, and a particularly inconvenient feeling was desire for the wife who had betrayed

him.

It was best to view her tactically, as though she were a fine rifle. The best tool to accomplish a job needing done, which

was restoring a measure of dignity to the Brightwall name in the eyes of the ton before he officially became an earl.

But bloody hell, he loved the way her face lit each time she was introduced to someone new, as if she was opening her whole

self to this person, inviting them into her warmth. Of all the tasks he'd been given when he was a little boy in the Coopersmith

house, where he'd grown up—so many of them vile, so many of them only tasks the other servants didn't want to do—he'd loved

best carrying a candle with him through the halls to light the sconces. It had always felt like magic to him that one little

flame could create so many others. And that's how he felt with Alexandra on his arm as he made introductions and greeted every

titled, distinguished person in the ton—as though he were bringing her light to them.

He noticed, too, how all the men looked from her to him and back again, with envy, or wonder, as if he was some sort of mad genius for marrying such a beautiful woman.

And sometimes they looked at him with sympathy.

Most unlovely husbands of beautiful women eventually learn the perils involved, as well, he suspected.

"Why, you don't look feral at all, Mrs. Brightwall," Lady Chisholm purred. "I'm almost disappointed."

Alexandra understood her mission—to enchant everyone to whom she was introduced, to make Magnus look like a genius for marrying

her, to restore gloss and dignity to the Brightwall name by appearing to be half of an exemplary, perhaps even slightly dull,

and devoted couple—and she'd had enough experience as a hostess to know how to tailor her approach to each new person.

Lady Chisholm was a bit of a doyenne: socially powerful, older, beautiful, and not, on the whole, a nice person, though she

was known to never be dull. Her striking green eyes had taken Alexandra's measure swiftly and her expression suggested a piquant

blend of guarded approval and acute and not entirely charitable curiosity.

The Earl of Chisholm had pulled aside Magnus, and the two of them were talking in low voices a little to the left of their

wives. Perhaps there was a special club for earls he was being invited to join once the Letters Patent creating his title

were officially filed by the king.

"‘Feral'! My goodness! What a powerful word. It's so fun to use, isn't it?" Alexandra replied cheerfully. "But please forgive me if I sound provincial when I confess to you that I'm not certain I understand the reference. Is ‘feral' something the fashionable set is saying this year?"

Lady Chisholm's eyebrows launched. Uncertainty flickered across her features.

"It was the word they used to describe you in the gossip sheets," Lady Chisholm finally admitted. "Forgive my little jest.

But it's part of the reason everyone is so eager to meet you this evening."

"Ohhhh." Alexandra gave a merry laugh and laid a gentle, friendly hand briefly on her arm. "I'm so sorry. I used to enjoy

reading them, but suppose I got out of the habit after I married. Because when I think of how Magnus nearly died in battle..."

She sucked in a sharp breath and squared her shoulders. "Well, the world is dangerous enough as it is, and after he nearly

died all I wanted to read was kind and gentle things. The gossip pages are often witty, but they're so seldom kind. Was it

at least amusing, what they wrote, if it wasn't kind?"

She gazed at Lady Chisholm hopefully.

Lady Chisholm pressed her lips together, nonplussed, and a trifle suspicious.

Alexandra radiated innocence at her.

"It was a drawing." Lady Chisholm's voice was rather subdued. "A Rowlandson drawing." As if that answered the "was it kind?" question, which, frankly, it did, and they both knew the answer was "no." She cleared her throat. "The article mentioned there was a bit of a to-do with a carriage, and..." She cleared her throat again, and added, somewhat hopefully, "Jail?"

Alexandra frowned. "Oh, Rowlandson . That rascal. I'm not certain what's meant by a to-do with a carriage, but it's almost an honor if Rowlandson chooses to draw a

person, regardless of the circumstances, don't you think? But if I may share something with you, Lady Chisholm, entirely in

confidence?" She leaned forward. "I know that Magnus looks like a fortress, and it's true he's very protective of me. I can

bear just about anything on his behalf, but do think any sort of unkindness toward me would hurt him, and that troubles me

so. Doesn't it seem like such a shame to cause pain for a hero who has already been so gravely injured?"

She gazed earnestly up at the countess.

Who stared back at her, speechless and clearly officially disarmed.

"You are right of course." Lady Chisholm sounded thoroughly chastised. "A shame, indeed."

"And I wonder if the newspapers are making things up out of whole cloth because Magnus has been away for so long, and I have

been in England with my family, and no one has had a chance to see us together. But he's back now. I think they will discover

the reality is much better, if also much less exciting." Alexandra smiled sweetly.

"I understand completely." Lady Chisholm was briskly earnest now. "Leave it to me, Mrs. Bright wall, to make certain no one brings up the topic to you again while you're our guest. They will need to answer to me."

"Thank you so much. Oh, I knew you would be thoughtful. You have that look about you."

"Have I?" Lady Chisholm, about whom such a thing had never before been said, was enchanted.

And then suddenly Lady Chisholm's head tilted way back to look up, which was how Alexandra knew Magnus had appeared behind

her.

A light warmth hovered briefly at her back. Magnus's hand.

Ridiculously, her breath hitched in surprise. Of course he could touch her. He was her husband.

But his hand didn't linger against her. Unless one counted the tingle left behind. She found herself focusing on it, in order

to make it last longer.

Lady Chisholm beamed at him.

"You must be so proud of your husband, Mrs. Brightwall."

"Oh, indeed. It's almost too much pride to bear," she agreed.

Out of the corner of her eye she saw the corner of Magnus's mouth twitch toward a smile.

"And how fortunate you are to have a wife who is such a credit to you, Colonel Brightwall," Lady Chisholm added generously.

"How proud you must be of her."

And a little shadow moved over Alexandra's heart at the notion that Magnus might be forced to lie right in front of her. Of

a certainty he could not truly be proud of her.

"I overheard her extolling my virtues to you a moment ago, Lady Chisholm, and I likewise cannot take credit for her charm. Only for recognizing it immediately."

Thusly he adroitly avoided answering that question.

The orchestra had begun playing the Sussex Waltz, and couples were moving out onto the floor.

He turned to her. "Mrs. Brightwall, I wondered if I may have the pleasure of this dance?"

Her heart accelerated oddly. She had never danced with him. "Of course, sir." She curtsied whimsically.

Magnus extended his arm, and he led her to the floor.

There was a reason the waltz had once been—still was, he supposed—considered scandalous. A man and a woman opened their arms

to receive each other, in full view of the public. Unlike a reel, or a quadrille, they spent most of the music face-to-face.

Which meant for the duration the man was treated to a long, uninterrupted view of the tantalizing tops of a woman's breasts

pushed up by her stays, should he drop his eyes from hers.

It was not much of a stretch from there for a man to imagine his dancing partner pinned to a mattress, urging him to go faster

and harder.

The minute leap of Alexandra's rib cage when he settled his hand against her waist made him feel both tender and nearly savage with possessiveness. Her small gloved hand disappearing into his made him feel almost violently protective. None of these feelings were rational. His feelings regarding her had never belonged to the realm of reason.

Simultaneously, as he reached for her, he recalled that a young man somewhere in the world knew the feel of Alexandra pressed

against his body, and her lips against his, and the memory of her in that man's arms applied ice to the low burn of Magnus's

longing.

But even before he touched her tonight, he knew their bodies had already started a silent dialogue. He had sensed it in their

suite, as she'd sat near him on the settee the other night. In the dark of the carriage. He could feel it on his skin the

way he could the promise of a thunderstorm. That crackle of portent.

He wasn't imagining it now, and he hadn't imagined it five years ago, when he'd sensed a spark. The male of every species

was exquisitely attuned to this sort of thing, he supposed.

Then again, it wasn't something one could really control. It was the sort of thing that could still roil beneath the surface,

even if they despised each other.

Through some miracle, he was certain she didn't despise him.

And they moved together, nearly oblivious to the other couples on the floor, many if not most of whom were watching them. His heart turned over to see himself reflected in her eyes, which were solemn, and searching. What did she see? A hard man, of a certainty. He was unequivocally that. He'd earned it. Not a handsome one. But the days when he'd longed to look like Hardy or Bolt were behind him; he did not see the point in longing for what could not be. He was seasoned enough now to appreciate about himself the things he had once rued, or suffered over.

He was perhaps foolish enough now to want to be wanted because of these things, not in spite of them. Wanted for everything

that he was, the way he had never been wanted as a boy.

"I overheard you laying waste to Lady Chisholm's attempts to perpetuate the Newgate gossip. Nicely done. You might recall

I told you once you'd make a good diplomat."

"I'm not certain how admirable it is to admit this, but I found it rather invigorating," she told him. "Like a badminton match.

Perhaps I haven't been challenged enough recently."

"I can't imagine stealing a carriage makes the best use of your talents. Perhaps you ought to diversify your pastimes."

She looked both uncertain and tempted to laugh. "You're teasing me," she hazarded.

"Yes. A little."

Neither one of them seemed very inclined to give each other leeway when it came to being charmed. Both were stubborn.

A slightly weighty little silence followed. If things had been different, they might have had a family of their own by now.

She would have, of a certainty, been occupied.

And he knew that despite the occasional speculative appearance in the gossip sheets, she had, in fact, been conservative about her entertainments over the past five years. He appreciated this. But he also felt a little twinge of guilt about it.

"The spirited discourse at The Grand Palace on the Thames ought to keep you on your toes," he said.

She did laugh then.

He'd forgotten her laugh was better than champagne.

"Do... do you like operas?" she asked suddenly.

He considered this. "I'm not really sure," he admitted. "I haven't decided."

Her eyes lit with amusement and curiosity. "Some are easier to like than others," she agreed.

"It's just... I'm still trying to learn what leisure pastimes I enjoy." He was a little embarrassed to admit it. "I've

been a soldier for so long, and I've had little time for leisure pursuits since I was sixteen years old. Apart from the sort

of leisure pursuits boys get up to. Shooting targets, five-card loo. Curse words. Fistfights. And I've been trying this and

that."

She studied him with soft, intrigued sympathy. He felt a trifle abashed.

"Let's see. You like horses..."

So she was going to help him discover his pleasures and pursuits, and damned if he wasn't touched.

"All animals."

This made her smile. She thought a little more. He looked forward to what she would come out with. "Gardens?"

"Yes. Trees, flowers, and gardens, both the very tidy kind, because it appeals to the soldier in me who likes to see things

in formation, and the wild kind, because I rather admire the tenacity of anything that tries to be fully itself."

She looked rapt. "The ocean?"

"Yes, very much," he said quietly.

He suspected she was offering a list of things she loved.

"Ocean voyages?" She was tentative.

"Yes," he said gently, after a moment. Knowing she would be embarking on her first in a few days.

"And you like reading..."

"I do."

Suddenly her eyes were dancing. "If you were a fountain, what sort of fountain would you be?"

He gave a little shout of laughter. Then he sighed. "Mrs. Pariseau is invigorating."

"I thought so. And I rather like her prickly friend, too. Mrs. Cuthbert. She's like a dash of pepper in the stew. Or that

one ingredient you're not certain you like, but which makes things interesting."

"Mrs. Cuthbert is likely just a bit too stimulated. Frightened creatures use whatever defenses they have at their disposal,

and hers is disapproval. Other people throw gloves and slippers."

Her eyes flared in surprise, and a flush moved into her cheeks. But she didn't relinquish his gaze; she in fact inspected

his face rather fiercely. Whatever she saw there made her eyes shine.

"And I would be an indestructible fountain, and I would never run dry, so that any thirsty creature who wants a drink can come and have one. How it looks matters not a bit, as long as those things are true. Perhaps it's a great block."

Her eyes were shining with delight now. "I'm certain people would come from miles around for the honor of drinking from the

great block."

He laughed.

"Speaking of frightened creatures, I wonder how Lord Thackeray is faring in Newgate," she ventured.

Bloody hell.

Perhaps she liked her chances of persuading him while she was wearing that dress, and after she had just charmed him. He had

to admire the tactic.

"Oh, he might be sharpening a stool leg into a shiv as we speak. Or bartering his shoes for food."

Charming men who were a bit feckless had a place in the world. But Thackeray had endangered her and Magnus remained quietly,

implacably furious about it. Thackeray's crime—his mistake , as it were—was ridiculous. A grown man had no business being such a fool.

"There was a time when you told me you were disinclined to judge people," she ventured.

"It isn't judgment to allow people to experience the consequences of their actions," he explained, tersely.

And that's when he saw her jaw set.

"Of course not," she said, with great irony. "And I suppose people also tell you what punishment they deserve with their actions."

And just like that, tension simmered. Because now they were talking about her, and him, and their wedding night.

"In my experience, unfailingly," he said simply, which he knew would madden her.

He didn't know why he liked the fact that she had a temper. It wasn't the spoiled or capricious sort; it arose from a defense

of her rights and convictions, and he wholly respected it, even when he disagreed with her.

A silence fell for a bar's worth of the music.

"It's just... Thackeray is my family." She said this somewhat resignedly. Sadly. With the faintest hint of despair. "Maybe

you don't..."

She pressed her lips together. He thought she might have intended her next word to be "understand."

They both knew he had essentially rescued her family once before, in exchange for a wife who had immediately proved faithless.

And not once had he complained about his bad bargain.

"I do understand why you are concerned for your cousin's welfare," he said with a certain strained patience. "And I appreciate

your sense of responsibility. I never knew my own family. But I look after Mrs. Scofield, the housekeeper from the home where

I was raised. She's the one who found me as an infant."

He wasn't certain why he'd told her about Mrs. Scofield. His reasons for paying for her keep during her retirement were, in fact, a bit complicated. And he wasn't certain he understood all of them, himself.

"It's good of you to care for her," she said politely. "I imagine Mr. Lawler has been paying her bills, as well?"

"He has been, yes. Her lodgings are in fact near the park. Before the statue unveiling ceremony, I'd like to pay a short visit

to her to ascertain everything is well."

"Very well." She paused. "I should like to meet her."

They didn't speak for a time; they merely moved in the dance. Embers of rancor still smoldered. But their eyes remained fixed

upon each other's faces. He could not seem to think of a reason to look away, when she was the only thing he currently wanted

to see.

Finally he said, "I apologize if you should like to dance a reel this evening. I'm not certain my leg is currently equal to

it."

It was both a tactic to break the tension and, alas, the truth.

Her face suffused with softness at once and everything in him yearned toward it as though it was one of those cloudlike pillows

at The Grand Palace on the Thames. But then, he knew she was just naturally kind. He needn't read a thing into it.

"Oh, my goodness, please don't apologize, Magnus. I have danced countless reels in my life, and I find social badminton invigorating

enough."

He nodded.

"And besides," she added. "We have a curfew."

"Good God, I nearly forgot."

This made her smile again. Her smile faded. "Does it bother you often? Your leg."

"If I spend too much time on my feet without resting a bit, or if the weather is turning... it will remind me," he said

ruefully. "But mostly it reminds me of how lucky I am to survive the war long enough to dance with you while you're wearing

that pink dress."

He'd said this aloud despite every instinct to the contrary.

Perhaps because he was so painfully full of unsaid things, he craved the release of just one of them. Perhaps it was because

touching her, and being close enough to her to smell the fine soap she'd used and the lavender in which her gowns were stored,

would erode his control a bit at a time if he let it.

Perhaps because she still had so much power over him, he'd wanted to know whether he could move her.

He was rewarded when he felt that precious little jump of her rib cage as her breath hitched.

Her cheeks were blooming pink.

"We're all lucky you survived the war," she said softly. And, it seemed, carefully.

His smile was somewhat ironic. If he'd died on the battlefield, they never would have married at all. He wondered if she'd

ever entertained that possibility. He wouldn't have blamed her one bit.

Fullepub

Fullepub