Chapter Six

If he had instead arrived during the gray light of dawn.

Or in the full dark of evening.

If his exquisitely tailored civilian clothes hadn't felt foreign against his skin after years lived in a scarlet uniform,

as though he was an ill-rehearsed actor wearing a costume.

If he hadn't felt awkward and uncertain without a sword at his hip or a rifle in his hand, as though he had just lost a limb.

If he hadn't spent most of his life superbly negotiating that razor-thin line dividing the tedium and terror of warfare and

had yet to discover who he was in a world that now required little more of him other than to let it fête him and put him on

a pedestal.

If all of these things hadn't caused the usual chain mail of his defenses to slip.

But he'd arrived at the Bellamy house at noon that fateful day.

And if the white marble foyer hadn't been gleaming like the halls of heaven in the noonday sun, perhaps she wouldn't have looked to him like an angel gliding toward him. Perhaps the sun wouldn't have gilded the crown of her coppery hair, and her sheer muslin dress wouldn't have floated tantalizingly about her lovely body with her every light, quick step. Perhaps he wouldn't have noticed the little russet and gold flecks floating in her clear hazel eyes like leaves on the surface of a clear pond when she looked up at him for the first time. Perhaps he wouldn't have seen the flicker of shy uncertainty in them—he'd seen that expression many a time in the faces of women, sometimes tinged with pity, or wary solemnity, even fear—give way to warmth and a sort of dancing light.

He knew what she saw: a cool, fearsome edifice of a man.

But it seemed at once to him that her essence—crackling yet gentle, brave and singular—shone from her eyes.

Once when he lay bleeding on a battlefield, a hail of moments from his life had pelted his consciousness, each distinct as

a portrait. The first time he saw The Honorable Alexandra Bellamy was a bit like that: a few thousand simultaneous convictions

and desires assailed him.

He would kill for her.

Or die for her.

Whatever she required of him, he would do it.

He could very clearly imagine murmuring filthy endearments in her ear as he took her up against a wall, her eyes hazed with

bliss as he moved in her body.

He wanted to curl an arm around her, draw her gently into his chest, fold himself around her to protect her for the rest of his born days.

He wanted to give her things: Money. Jewelry. Flowers. His name. Babies.

He wanted to know what made her eyes dance.

He wanted to be the reason her eyes danced.

He felt simultaneously ancient, as primitive as the first man, brand-new, blank of mind and absolutely surging with base needs,

and like the shy, homely hulk of a boy who'd always known he wasn't wanted, that he was, in fact, alive on sufferance, so

he'd made bloody certain he was needed.

He knew in his bones there was no way a woman like her would want a man like him.

She was the sort who would marry a duke. He wasn't the kind of man who would haunt the dreams of a woman like Miss Bellamy,

unless he took the form of a creature lurking in a maze, like a Minotaur. Which, coincidentally, was just one of the things

the newspapers had called him over the years. He'd needed to look the word up. He'd been darkly amused but not dissatisfied

to be compared to a mythical monster. He remembered vividly how it had felt to be at the mercy of others' charity. To have

no defenses at all.

When he was a boy, he had silently wept the first time he'd been called a beast. He had long since recognized the power in

the word. He had claimed it for his own.

He wasn't erudite, like General Blackmore, who was now the Duke of Valkirk. He hadn't a classical education, like so many army officers who had bought their commissions and subsequent promotions. The kind that aristocratic gents had, where one would say something about, oh, Aristotle, and they would all laugh and nod sagely. It was their shared language, a sort of password into their society.

But he was confident of his own unique brilliance.

And if "charming" was seldom the first word people used to describe him, perhaps it was just because there were so many better

choices. All the "F"s, for instance: Fierce. Formidable. Forbidding. Frightening. "Bastard" was trotted out with relative

frequency, used both literally and figuratively. All of this was true, so none of it bothered him. But he hadn't soared through

the ranks of the army on skill alone. Those who mattered liked him for other reasons. He could be insightful, even sensitive,

in a way that never compromised a man's dignity. He was frank. His sense of humor trended toward dry and black and his integrity

was impregnable. The men under his command would walk through the fires of hell for him, because they knew he would do the

same for them.

He didn't know how to court a woman. There had simply never been time for such grace notes in his life; he'd bought his commission

with earnings from a shooting contest he'd won at age sixteen.

But one advantage he had over all of these aris tocrats was that he knew how to revere even the smallest moments of beauty and pleasure. For all of his had been rare, fleeting, and hard-earned.

He knew he could make a woman laugh.

And he knew how to make a woman come.

When he laid eyes on her, he understood after sixteen years in the army, his soul was at last sore and weary from bearing

the weight of grief and death and responsibility and the mantle of triumph and a nation's gratitude. In her presence he'd

felt that weight lift and shift long enough to imagine what his future could look like.

No one knew better than he did that peace was an illusion. But he understood at once that the closest thing to personal peace

was a sense of "rightness." And nothing had ever felt so right to his soul as her.

He knew nothing about love.

But he knew how to cherish.

And he bloody well knew how to win.

Within days of his arrival he'd decided she would be his before he left for Spain.

But today, when he'd seen those women gathered around Alexandra in that Newgate cell, their faces turned up to her as though

she was the fire on a hearth, her own sweet face open and welcoming and drawn with fatigue, he understood that not a damn

thing would have made a difference. No matter when, no matter how he'd first seen her, the result would have been the same.

Somehow, she was now embedded in him, like that shrapnel in his leg.

She hadn't wanted him then. He'd known that.

But he'd understood full well why she'd married him.

He'd counted on it, in fact.

And he knew she would have likely patiently and kindly endured her marriage to him, because she was patient and kind. She

would perhaps always view him as something of a savior, and he would have been apportioned gratitude for that, too.

But he'd been convinced there was a spark between them.

As a man who had built many a fire with flint and steel, he knew even the tiniest of sparks could be fanned into a conflagration.

In his hubris, he had thought himself perfectly capable of building that between them. All it required was time, and he would

have had the rest of his life to do it. He would have, as the vows said, worshipped her with his body.

Well.

He'd presciently anticipated French troop movements during major battles.

But he had failed to consider that his twenty-two-year-old wife might already have a lover.

At least history was rife with formidable men who had proved to be fools when it came to one particular woman.

Since he'd needed to leave for Spain the day following his wedding, he'd had mere hours to decide upon the right and just

thing to do.

Ultimately, he'd done what felt like the just thing.

But he'd had years to contemplate whether he'd done the right thing.

He still didn't know.

Even now, he couldn't quite forgive her. He simply was not made that way. Although sometimes he thought all this meant was

that he couldn't quite forgive himself.

He'd gone to ask the staff of The Grand Palace on the Thames to prepare her a bath and bring her a little meal—there was an

extra charge for both, the proprietresses had sweetly informed him, although breakfast and dinner were of course included

with their board—and he would be going out again to order the town house servants to pack trunks for her.

They'd never spent a single night together.

And even though in the eyes of the law she was his, it seemed intrusive and wrong to watch her sleeping, while she was unaware

and vulnerable.

But he lingered a moment anyway.

She remained the most beautiful woman he'd ever seen. And even now desire pulled his muscles taut.

It wasn't precisely about the arrangement of features, which were inarguably lovely when considered together and separately:

her bold hair and her soft eyes; her full pink mouth and her long slender neck; her generous curves and her clean, sharp jaw.

She was a mesmerizing study in contrasts.

From the first he'd felt her as much as, or more than, he'd seen her. Something happened to his insides when she was near. He'd come to think of it as his entire being pulled toward her, the way the moon relentlessly lures the tides to the shore.

But perhaps even this feeling hadn't any of the profundity he'd ascribed to it.

After all, he'd been shot because there was a war on. That had merely been a consequence of circumstance, with lifetime ramifications.

Perhaps how he felt around her was only that. Perhaps because he'd no other experience of love, he'd built it into something

grand in his head.

Perhaps a brute like him ought never to have aspired to a woman like her.

Even an imbecile knew that if you closed your fist around a little flame in an attempt to keep it, you extinguished it instead.

And, of course, you also got burned.

He gently laid her slippers on the braided rug next to the bed. As if by way of apology for being the cold bastard who had

caused her to throw them.

He found no relief from his own pain by punishing her with coldness. Only a weariness, and a nice little smattering of self-loathing.

He had meant to take care of her for the whole of her life.

And even though she'd betrayed him, he still, somehow, felt like he'd failed her.

He'd never asked Mr. Lawler or anyone else to spy on her. But in his subtle, almost admonishing way, Mr. Lawler had included informa tive little sentences in his expense reports: "As Mrs. Brightwall never spends an entire evening away from home or entertains guests at night, I am confident the expense of a new gas lamp will be offset by the reduced need for firewood." That sort of thing.

But she was young. He had no doubt she was passionate. There would come a day when she would bring a lover home.

He did not think he could bear that.

Enough was enough. It was time to settle the thing between them, so they could move on with their separate lives.

And the day when he'd wanted to be alone was long past.

He settled the coverlet over her, making sure to cover her stockinged toes.

By the time she'd stepped out of the bath a pair of cheerful maids had hauled up the stairs for her, a small trunk of clothing

had arrived—Magnus had arranged for the town house maids to pack and send over day and evening dresses and all the furbelows

that went with them, including hairpins. She'd devoured two scones clearly baked in heaven's ovens and the accompanying slices

of cheese, cold chicken, and soup. She drank half a pot of tea.

She was warm, clean, fragrant, and fetchingly outfitted in a bronze silk day dress when Magnus handed the newspaper to her.

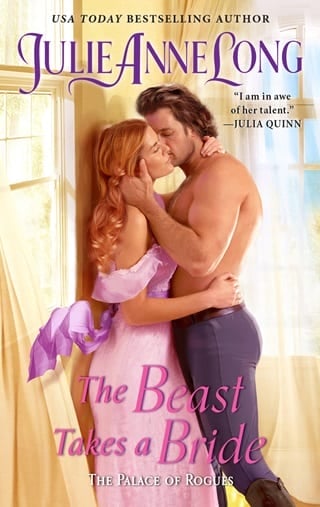

Brightwall the Beast's Feral Bride Takes on the Army

Now we know why Brightwall keeps his bride hidden away: she runs amuck when let off her lead. It took an entire battalion

to contain her when she took it into her head to help steal a carriage.

The illustration accompanying the little passage depicted her with arms and legs whirling. Her mouth was twisted in a snarl.

Her hair, however, looked wonderful. It was lusciously arranged. Not a lock out of place. Rowlandson, the infamously, caustically

witty caricaturist, had outdone himself.

It was the most peculiar sensation. Half of her found it so transcendently funny she nearly elevated out of her body. The

rest of her was so scorchingly embarrassed she wished the ground would open up beneath her and suck her under.

She lifted her eyes to her husband's. He sat across from her at the little table near the window in the room.

And for a vanishing instant, humor crackled and arced between them.

In other circumstances—or if they were different people—they might be able to laugh at this together now.

She cleared her throat.

"The little swirls in front of my nose..." She pointed. "I suppose I'm meant to be snorting?"

"Yes. I believe so. Like a bull. Because we're both meant to be beasts. You're snorting like a beast. Mrs. Beast."

One little drawing could hardly devastate her if all of the other vicissitudes of her life hadn't yet. Rowlandson was famously

merciless to everyone.

If, however, it carried on... if the ton at large decided the Mr. and Mrs. Beast theme was great fun—and she could easily

see how they would—it might never end. There might be endless variations of those images, the way there were apparently endless verses of "The Ballad of Colin

Eversea."

The idea of this wasn't funny in the least.

It was odd. Somehow, sitting here in this pleasant suite, fresh from her bath, it seemed so easy not to do anything to besmirch

her husband's good name. Let alone wind up in jail and become an indelible Rowlandson caricature. And yet the evidence that

she had managed to do just that was undeniable.

"I expect you can imagine the potential ramifications of this." He said this almost dryly.

"Yes." Her voice was frayed. "I am imagining them now."

"I have a sense of humor, Alexandra. But it's quite another thing to be viewed as a public laughingstock. Another man might

find the patience within him to stoically tolerate the... relentless illustrated campaign that might ensue." He paused.

"I find that I am not that man."

She could feel her pulse ticking in her throat.

She swallowed hard.

"No. You should never have to tolerate it."

"Your conduct is a reflection on me." He stated this evenly, as fact.

She nodded. She found she could no longer speak.

"I was called back to London in part because there have been talks to the effect that the king intends to create Letters Patent

designating me the Earl of Montcroix. It will be a hereditary title. Should this come to pass, this of course means your title,

for the rest of your life, will be the Countess Montcroix."

She blinked. She was stunned at what seemed a sudden and glorious change of topic.

Genuine joy suffused her. "Oh, my goodness. Congratulations, Magnus. That is quite extraordinary. Nobody deserves such an

honor more."

He merely nodded. "But the warrant instructing the Lord High Chancellor to prepare the Letters Patent creating the title has

not yet been delivered to him. As you are no doubt aware, His Majesty's popularity is a tenuous and fluctuating thing, a matter

of much concern to him, as he wishes to be beloved."

He said this rather dryly: there really was no hope of King George becoming beloved. He'd made his own bed, as it were. And

as it so happened, parliament refused to grant the king his divorce, which had been a process so thoroughly messy and degrading

and public it ought to discourage anyone from attempting a divorce in England for decades to come.

"And he still might conceivably decide he'd look even more foolish if he elevated to the aristocracy a man whose wife had the poor judgment to consort with an alleged carriage thief, even if the thief was her hapless third cousin Lord Thackeray. Needless to say, even more attention will be called to the alleged carriage theft if I am indeed made a peer of the realm."

And now she was alarmed.

Oh God. Her poor cousin! Was he still in prison?

"In light of this recent event, and for other reasons, it is increasingly clear to me that, in order to live our lives with

dignity and peace, it is best if we effect as permanent and complete a marital separation as possible within the limitations

of the law."

Her breath left her. She stared at him as if he'd whipped out a broadsword.

Ice flooded her stomach again.

He'd made it clear to her on their wedding night that both divorce and annulment were out of the question, as it would be

nearly impossible—even attempting one would be financially and socially annihilating for both of them, and particularly humiliating

for him. The granting of a divorce required an actual act of parliament and public hearings. Her family's name would be tarnished

forever, and she in particular would become a pariah. The one—the only —impulsive, foolish, brief indiscretion she'd ever committed would become not only national knowledge, but part of English

history.

"He knew I was happiest here in England, among my family," was all she'd said when anyone she knew inquired about his absence. "We correspond regularly. He will return one day."

None of this was entirely untrue.

She always adroitly and firmly steered the topic of conversation to generalities when the subject arose.

And Brightwall had, as he'd promised the evening he'd outlined her fate, remained entirely silent on the subject. He'd merely

nobly fallen on his sword.

Regardless of what she told him, her father had clearly been distressed for her. And he felt a little guilty. But his position

was awkward, indeed: he was disinclined to suggest the man who had saved his entire family from penury had subsequently cruelly

abandoned his daughter. Alexandra knew he felt he hadn't a right to confront the colonel. Alexandra had assured him that she

was content with the conditions of her life, and wanted for nothing. And this, on the face of it, was true, too. At least

as far as material comforts were concerned.

"This is what I propose," Brightwall continued calmly. "Over the next week, we will appear together at several functions—a

ball, a banquet and reception, a statue dedication—to be held in my honor, and present ourselves as a united, committed, entirely

civil and civil ized couple, thereby putting paid to any malicious gossip and restoring, to the extent possible, dignity to the Bright wall name. At the end of this period, you will then travel as planned to the United States. You may recall that I own an estate near New York, near, in fact, where your brother now resides." He paused. "I've long thought someone should be in residence to look after the home and the lands. I have been considering going to stay for some time, when my duties allow it. Instead, I should like you to stay there."

Her breath was coming shallow now.

"For the duration of my visit to my brother?" Her mouth had gone dry.

The eloquent pause betrayed his answer before he said the words.

"For the rest of our lives."

He said it almost gently.

The world seemed to tilt; shock flickered her vision from brilliant to black and back again.

"I will deed the New York property to you, and settle upon you a single sum large enough to live for the rest of your life

in a manner both comfortable and gracious, including the keeping of horses, if you choose. You will be at liberty to hire

your own staff and make decisions about purchases. To the extent possible, you will thenceforth be entirely free of me."

Her breathing had gone shallow.

She couldn't feel her limbs.

Had she expected rapprochement?

Had she even wanted it?

"So I'm to be sent to Elba, is it?" Her ears were ringing. Her voice was pitched unnaturally high.

"New York is no longer the wilds, nor is it isolated, nor will you be alone. And unlike Napoleon, you did not preside over the slaughter of thousands of Englishmen."

"No. Just the one apparently," she said bitterly.

He didn't reply.

He did, however, look a little white about the mouth.

He clearly wasn't enjoying this, either. Just as he probably hadn't relished ordering deserters shot. It was simply something

that had to be done.

"And if I do not want to stay there?"

Her dread swelled anew at his lengthy silence.

"Your income will be reduced to an amount required to purchase necessities. As for housing, I imagine you will be able to

live with your sister and her husband or with your father, should he return to England."

He said it quietly.

He had clearly thought everything through. Naturally.

A fleeting, blindingly pure hatred for the man sitting in front of her flashed through her.

He had no obligation to be generous, of course. But until the end of her days or his, he would be required to financially

support a woman who was his wife in name only. He could go on to have children with a mistress one day, if he chose. So many

men did.

No such option remained to her. She could of course bear children, or take a lover. But that would mean living on the outskirts of respectable society for the rest of her life, and the taint of that would touch everyone in her family.

Her breath seemed to scrape her lungs on its way in and out.

It was hideously unfair how profoundly he excelled at not blinking.

"If you tell me you're happy with your life as it is... I will know you're lying, Alexandra." He said this almost gently.

"It seems very clear that we are not a successful match. I have learned from warfare that life is short and that wallowing

in regret is... such a waste of time."

Her eyes had begun to burn.

Do not weep do not weep do not weep.

She couldn't speak.

"I'm not happy, either." His words were scarcely audible. As if he was ashamed to reveal any kind of vulnerability.

His tone wasn't accusatory. It didn't need to be. Her own conscience flailed her.

"I think such a change will be beneficial to both of us. If you agree, you might find comfort in the fact that soon you need

never see my face again."

Was this what she wanted? It wasn't the sight of him that tormented her. It never had been.

She forced herself to think about it. If she lived an ocean away, she could perhaps cease hearing about him so frequently, or reading about him in newspapers, and perhaps, as the years went on, even wondering overmuch about him. And perhaps the fact that she had inadvertently ruined this man's life would become a distant, dull echo in the background of hers. It would bother her the way the shrapnel in Brightwall's wounded leg bothered him.

Like little fissures of air in a sealed coffin, tendrils of possibility began to wind through the dark snarl around her heart.

The notion of an entirely new life, unfettered by obligation to a man, any man, did indeed seem like freedom. Nor would she be obligated to solve the problems of her family. They were all thriving,

thanks in large part to Brightwall's money. God knows where they would all be now if she hadn't married him.

It would mean leaving everything she knew behind.

But suddenly this notion seemed almost exhilarating. And even though the decision would always be bound to a certain sadness

and guilt, she had learned that one couldn't get through life unfettered by regret. She had loved and been loved by a young

man once, briefly. Perhaps that was all one got in a lifetime. She wouldn't be the first human who had changed the course

of her life with one fateful mistake.

All at once she realized Magnus had hit upon the right solution.

She swallowed hard.

She dragged in a breath and settled her shoulders on an exhale.

"Although I of course have no rights that you haven't bestowed upon me, I agree to your terms. I will appear at your side for the events in your honor, and then I will go to live in New York."

There seemed a terrifying finality in even saying the words.

His shoulders rose and fell as he exhaled in what sounded like relief.

"But what if our performances as devoted spouses prove unconvincing to the ton?" she asked.

"As your own reputation and your family's reputation are also at stake, I have no doubt you will acquit yourself well."

In other words: It's clear to me that I don't matter to you, but your family does, Alexandra .

This wasn't true. But she wasn't going to belabor the point. She would do her duty, because that's what she'd always done,

and then they would be as finished with each other as was possible.

"I'm afraid that doesn't entirely answer my question," she managed to say calmly.

He understood. "If at any point it becomes clear to us that we cannot convincingly portray a devoted couple, and if it appears

we are in fact making things worse, rather than better, we'll end our arrangement at once. You may proceed to live with your

sister. I will leave it up to you to explain to your family why you will not be occupying any of my properties."

He really was such a cool, unmitigatedly ruthless bastard. It was utterly impressive. She might even have been proud to witness it, if she hadn't been the one cornered. He knew full well she was too proud to go and live with her sister, let alone explain to her sister why her marriage had failed.

She recalled well what he'd said about there being no pleasure in stripping a man of his pride. His armor, he'd called it.

Magnus took his seriously.

And so did she. It went down jaggedly as she swallowed it now.

"I'm certain I can manage to be a credit to you long enough to fool the ton." She managed to say this with just a frisson

of irony.

He nodded.

After a moment he said, "I always did think you would be a credit to me." He said it quietly. Again, no recrimination. Simple

truth. He sounded almost puzzled.

She dug her fingernails into her palms to keep the tears from spilling from her burning eyes.

She cleared her throat. "Before we formalize our agreement, I have a request."

His eyebrows leaped.

She pulled in a long sustaining breath. And then she pulled in another one, because the first wasn't sufficient to fuel her

nerves.

"I expect the habit of ordering people about dies hard. I understand that you are accustomed to getting soldiers to jump to do your bidding with sharp commands and to frightening subalterns with stony looks of displeasure or icy silences. In the context of war, I imagine these are very useful skills. I am... struggling to say this politely. I'm not a soldier, Magnus. I understand you have a grievance, but bullying is beneath you. I fear I simply will not respond to orders . I ask that for the duration of our agreement you treat me with the politeness and respect you would a partner. Because I

have discovered that I am willing to throw things if that's my only recourse and I cannot promise I won't do it again, even

if we're in the middle of a ballroom."

He had listened to most of this in absolute rigid stillness, apart from his eyebrows flicking with amazement.

Then his jaw had set.

But halfway through this recitation he'd propped his elbow on his knee and placed his chin on his hand, his expression absorbed.

Listening to, and watching her.

And damned if his expression hadn't reflected something like rueful admiration.

When she'd finished, her heart was knocking so hard it seemed a miracle that neither of them could hear it.

They regarded each other intently.

And for an odd moment, a slippage in time, she saw him as if for the first time, outside of the context of all she knew of him. Almost as if another woman entirely was sitting beside her and asking: "Who is this man?" She noticed how beautifully his dark coat fitted across his shoulders. She noticed the noble set of his head, and his remarkable, weathered, singular face, and the burn of his pale gaze, and how his thick, hard-muscled thighs pushed against the nankeen of his trousers. His presence was so weighty , so thoroughly intimidating and compelling, it left her nearly airless. It was impossible to imagine a circumstance over

which he wouldn't triumph.

But the shadows around his eyes looked less like fatigue, and more like grief.

He had meted justice to her, but she would warrant he had paid a cost in loneliness, too.

Finally Magnus straightened again, and pressed his lips together. He pushed a hand through his hair.

"Everything you've said is correct," he said simply. "I apologize sincerely for being a rude bastard. You have my word I shall

endeavor to be respectful. And consider this the last time I say ‘bastard' within your hearing."

She shakily released the breath she'd been holding. "Thank you." Her voice was scraped raw.

"But if you take a notion to throw things... you may have noticed my reflexes are excellent."

She made a soft sound. Not quite a laugh.

She ducked her head because she didn't want to dash tears away from her now-brimming eyes while he was watching.

She'd never wept easily, and almost never in front of anyone else; she supposed that was pride, too.

"Alexandra." He said it softly. But the word was taut with emotion.

She glanced up in surprise to find he was extending a handkerchief.

She could have sworn his hand was shaking a little.

She glanced from it to his face and discovered there was a peculiar tension around his eyes.

She stared at him, suddenly wondering if he'd ever wept over her while he was alone in Spain. Did he ever weep at all, or

had war evaporated all of his tears forever? Perhaps he'd simply been born incapable of ever being thoroughly crushed.

But she thought of that ribbon scrap in the box.

She took the handkerchief from him. "Thank you." Her voice was thick.

"I expect you'll want to rest more before dinner. I'll return before then," he said abruptly.

The door of their suite closed behind him seconds later.

Fullepub

Fullepub