Chapter 7

Emily felt sorry for Tom Sadowski. Here was a guy who had no idea this morning that this was how his day was going to work out: lead detective on a robbery at an art museum—which was clearly not his milieu; believing that with five men in custody he had a relatively easy crime to solve; and now being told by his boss that the woman in the Alexander McQueen suit was to have an integral role in the investigation.

What's more, it was clear that Detective Sadowski found her attractive and would undoubtedly make one or two ham-handed passes at her later, even though—being the good detective that he was—he knew she was out of his league.

Well, out of his league, and gay—although she doubted Detective Sadowski had picked up on that yet. He struck her as the type of man who believed lesbians didn't look like her, should have buzz cuts, and have names like Marge.

Didn't matter…

All that mattered was that he was being told by his boss to cooperate fully, and that she knew she could use her sex appeal to keep him compliant.

His partner, Andie Fuller, wouldn't be a problem, either. She was cute in a workaday way, but obviously straight. In any case, Emily's read on her was that Fuller was the pupil, and Sadowski was the master. Probably a newly-minted detective afraid of screwing up, which meant all Emily had to do was keep Sadowski in line until she concluded this case to her satisfaction—which meant finding The Young Shepherdess.

She would need to file a report on three of the other paintings involved in this case, which Geneva Excess also insured, in order for the company to eventually write a check for any damage that had been caused to them. As for the other two—including the Rembrandt—Geneva Excess didn't insure those, and so another investigator would be assigned to them.

Right now, The Young Shepherdess was her priority.

However, for the moment, she had to tell Detective Sadowski just how far off the mark his working theory was.

The detective pulled the phone away from his ear and re-clipped it to his belt. Emily hadn't seen a man wearing a phone on his belt since about 2010, but to each his own.

"Well, Detective?" she asked.

Sadowski sighed.

"You got here fast," he said.

Emily smiled.

The San Diego Museum of Art wasn't in the same category as the Louvre or the Met, but nor was it the Kentucky Museum of Horse Racing. The people who ran this institution, and the people who supported it with their deep pockets—not to mention the individuals who loaned artworks to it, were not the types to be kept waiting. Nor were the people who insured such institutions.

"Money, Detective," she said. "When valuable things go missing, the people those things belong to tend to want quick service."

"Since we're going to be working together," Sadowski said, "why don't you call me Tom?"

Emily smiled.

"Thank you," she said. "I'm Emily."

Tom nodded.

"Great," he said. "Now that we're on a first-name basis, why don't you tell me what you were talking about a minute ago…about me being on the wrong trail."

He crossed his arms and looked at her smugly, as though already anticipating the moment when he would tell her how crazy she was, and to leave police work to the professionals.

Emily really did feel sorry for him.

She stepped away from Tom and moved towards the recovered canvases on the floor. She gestured towards those, and then to The Penitent Magdalene, which was a few yards away.

"What do all of these paintings have in common?" she asked. When an answer wasn't forthcoming from Tom, she raised her voice a little and added, "Anybody?"

But none of the uniformed officers or other detectives said anything.

Finally, Detective Fuller spoke up…

"They're all in the same room," she said.

Emily smiled at her.

Good girl.

"Correct," she said. "So, why would the thieves want to bother with having to go out into the rotunda to also steal The Young Shepherdess?"

"Because they wanted it," Tom said flatly.

Emily narrowed her eyes.

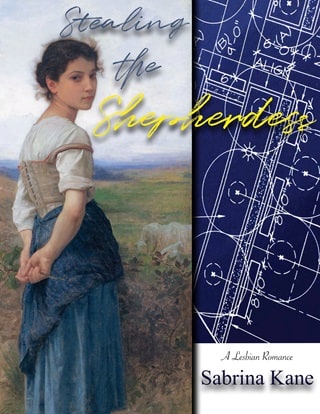

"Really?" she asked. "They were in here, in the process of stealing a Rembrandt—an artist whose work is considered priceless—and they decide to go after a painting by Bouguereau, which would fetch maybe two million dollars at auction? On a good day?"

Geneva Excess, whom she worked for, had the painting insured for that amount, but insurance values and auction values were two different numbers. The former was simply a result of an appraisal made by experts estimating a painting's worth, and then suggesting what would be an appropriate insurance payout. And as long as a museum was willing to pay the premiums, an outfit like Geneva Excess had no problem obliging them.

But an auction value? That was a completely different animal.

Bouguereau was not an A-list celebrity in the art world, like Rembrandt, Warhol, Da Vinci, or even Haring. Even people who had zero interest in art knew the name Rembrandt, but Emily knew serious collectors that didn't even know who Bouguereau was. In fact, Emily—who had been doing this for quite some time—believed The Young Shepherdess, if it ever came up for auction, would have trouble selling for a million-five.

"Also, why not just take the Rembrandt?" Emily went on. "It's the most valuable painting in the entire building! Why not just grab that one and leave?"

She saw Tom roll his eyes.

"Yeah, who knows how the criminal mind really works?" he said snidely.

Emily gave him a pitying smile.

"Actually, there's an entire field of study on how the criminal mind works, Detective," she told him. "I'm surprised you haven't heard of it. And I'm no expert on the subject, but even I think it's odd that these guys could have easily walked out of here with one Rembrandt, instead of wasting time pulling four other paintings off the walls which—combined—wouldn't equal a tenth of what the Rembrandt is worth."

At that moment, she saw it in Tom's eyes: the look which told her that he had come to the realization that she was right.

She approached the detective again.

"Something about this doesn't add up…" she told him.

The problem was, she still hadn't figured it out…

***

Priscilla left the Kroyn Tower after the Rahman meeting, which ended at about 4 o'clock, and had made her corporation 75 million dollars richer.

Mo Rahman was a jerk of the highest magnitude, and he came from a family in which seemingly all of the males believed women had been put on this earth to serve them. Whenever he had dealings with Priscilla, she swore that she could see the disdain and resentment dripping off him like sweat on a runner following a marathon.

Disdain because she was female.

Resentment because when small-dick men like him compared personal wealth, his was far, far…far below hers.

So, it had been with particular pleasure that she had been in the room when Rahman and his team of lawyers had finalized the purchase of an office tower the Kroyn Corporation owned in Los Angeles.

She had watched very attentively as her team of lawyers had given Rahman each of the many documents to sign in order to complete the sale. She had said very little during the entire transaction, letting Amélie and Heidi—her top real estate attorneys—speak for her, knowing they would handle her interests more than capably.

It was only after the final document had been signed, and the transfer of money completed, that Priscilla had told Rahman he had just paid 25 million dollars more than anyone else had offered. And then added that she hoped he had a nice day.

She planned on using that extra 25 million dollars to start construction on a new women's shelter in Los Angeles, near Skid Row. As a way of further twisting the knife, she was considering naming it after Rahman.

Now, Gordon was driving up the private road to her mansion on Presidio Drive.

"I won't need you anymore today, Gordon," she told him when he opened the Bentley's door for her. "Enjoy the night off."

"Thank you, ma'am," he said, touching his cap.

Priscilla walked into her curvy, Modernist home carrying the duffel bag in her left hand, and her slim briefcase in her right.

She was greeted in the foyer by Madeline.

Most people assumed Madeline was the housekeeper, but she was more like a Household Executive Assistant. She oversaw all of the operations of maintaining such a large house—including the staff—but she also took care of many of Priscilla's errands, and acted as an in-home personal secretary.

She was in her fifties, shorter than Priscilla, and had a runner's body.

"Welcome back, Ms. Kroyn," Madeline said in greeting. She then took Priscilla's briefcase, but did not try to take the duffel bag.

"Thank you," Priscilla said. She started walking to her den, with Madeline beside her. "Anything I need to be aware of?"

In the den, Priscilla placed the duffel bag on the sofa, and then Madeline told her about several phone calls from local friends trying to arrange get-togethers with her.

"And Ms. Worthington phoned," Madeline added, placing Priscilla's briefcase on the desk.

Priscilla sighed.

Susan Worthington was the youngest daughter of a fabulously wealthy family in La Jolla. She and Priscilla had a sporadic sexual arrangement—a friends-with-benefits type of thing. Lately, however, Priscilla had been wondering just how much longer she wanted to keep that going.

Somewhat regular sex was fabulous—and she had plenty of Susan Worthington-type arrangements with other women worldwide—but she had been noticing a distinct lack of personal fulfillment with all of them.

She'd have a think about how quickly she wanted to call Susan back.

"Thank you, Madeline," Priscilla said. "I won't be needing you the rest of the day. In fact, I won't be needing any of the staff."

"Would you like Diane to make you dinner?" Madeline asked, referring to Priscilla's personal chef.

"Um…no," Priscilla said. "I'm sure I can find something. I feel rather like having some time to myself, please."

One of the drawbacks of being so wealthy, Priscilla often thought, was that it seemed as if there was always someone around her, even at home. In addition to Madeline, Gordon, and Diane, she had a head housekeeper, a junior housekeeper, a groundskeeper, and a full-time handyman/lifter-of-heavy-objects/spider-killer. This was in addition to the rotating crew of security guards who protected the estate. With the exception of the security staff, all of the others had apartments in a separate building on the other side of the grounds, not far from the small guest house. The realtor who had sold her this mansion had kept referring to that building as the "servants' quarters," a term Priscilla disliked immensely. She herself called it the staff residence.

In any case, she often liked having this huge house all to herself, and when it happened, she relished the absolute solitude.

Today, in particular, she definitely wanted no one else around. She had some special work to do.

"Of course, ma'am," Madeline said. "Let any of us know if you need anything, however."

Priscilla smiled.

"I will," she said, sitting down at her desk. "Enjoy the rest of the day."

"Thank you, ma'am," Madeline replied, turning to leave.

Priscilla remained at her desk…waiting. She didn't do any work. Instead, she turned the office chair she was sitting in so that she was facing the window, leaned back in the seat, and placed her feet on the windowsill.

The window offered a view of the back of her property, high up on a cliff, beyond which was the Pacific Ocean. At the left edge of what the window was showing her was the staff residence: a one-story brick apartment building that was mostly hidden by a copse of small trees and shrubs.

It took about five minutes, but finally Madeline was seen walking along the path leading from the mansion to the staff residence. She was accompanied by the head housekeeper.

Priscilla got up from behind the desk and went to the sofa, opening the duffel bag and removing what she had taken from the museum.

She brought the rolled canvas to her massive desk, which was kept as uncluttered—perhaps even more so—as the one in the Kroyn Tower. She unrolled the painting, using her briefcase to hold it open at one end, and a paperweight which had been a gift from President Obama to do so at the other end.

Standing back, she looked down at The Young Shepherdess, and smiled.

"Hello, beautiful," she said.

Fullepub

Fullepub