CHAPTER 16

?^?

W inter stormed down from the north and punished the plains with a vengeance. Blizzards pounded the range with a frequency and ferocity that surprised even the oldtimers. In December, the temperature plummeted and didn't rise above zero for three weeks.

On bitterly cold mornings Louise and Max sat beside the kitchen stove, drinking coffee and waiting for dawn, dreading the necessity of going out into the driving snow to search for cattle in a blizzard. Many nights they half pushed, half carried stiff, half-frozen beeves into the barn and desperately tried to save them from freezing to death. Sometimes they succeeded; sometimes they didn't. It was an exhausting, heart-wrenching experience no matter how the effort ended.

All week Louise fervently looked forward to Sunday when the family came. Then she put on her lady skirts and shirtwaists and worked at preparing for the hard week to come. The work went easier when shared. This was the day the butter got churned, the laundry got washed, the rips and tears got darned and mended. On Sundays, she cleaned house from top to bottom, usually with Sunshine wielding a dust rag alongside her. Then before the men went back out to feed the beeves in the early evening, they all sat down to a late-afternoon meal. Afterward, Gilly played the parlor piano loud enough for Livvy and Louise to enjoy the music while they tidied up the kitchen.

No one mentioned Philadelphia except to comment occasionally that her father had sent his carriage to take her into town; otherwise Louise assumed Philadelphia stayed at the main house alone.

Louise didn't really expect Philadelphia to visit the man she should have married in the house he had built for her. Her presence would have made everyone acutely uncomfortable. But it was also true that Philadelphia 's refusal to join the family created a subtle tension that ran beneath the Sunday gatherings like a dark undercurrent.

"Aunt Louise?"

Abruptly she realized that Sunshine had called her twice. "Sorry, I guess I was woolgathering."

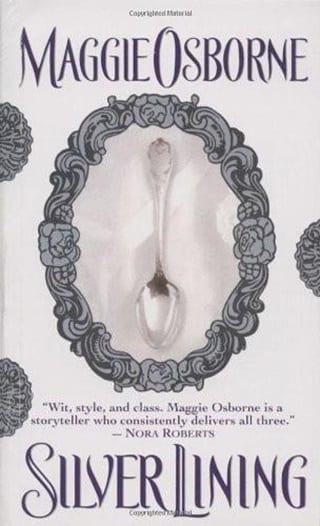

"Mama has lots of items on our parlor mantel, but you only display that one spoon. Why don't you put out other things, too?"

They had finished dusting the piano and parlor furniture, and now Louise was polishing her spoon. She liked to feel the cool smooth weight in her hand, liked to polish and rub until her reflection peered back at her in the shiny bowl.

"This is the nicest thing I ever owned, and it's special. It's the only thing I have that's good enough to display."

"Why is the spoon so special?"

"I'd like to hear the answer to that," Max said, appearing in the archway.

Snowflakes sparkled in his dark hair and on his lashes. Melting snow had dampened his shirt collar, and his cheeks glowed pink with cold.

Louise decided yet again that he was the handsomest man she had ever laid eyes on. It amazed her, simply knocked the air out of her chest that this splendid man was her husband. She could not believe that in a few hours they would climb into bed together and share each other's warmth and bodies. A flush heated her cheeks, and she looked away from his smile and back down at her spoon.

"This spoon reminds me of a schoolhouse and your uncle Max. I like to look at it and hold it in my hands."

"That old spoon?" Sunshine asked, puzzled.

She nodded, avoiding Max's steady gaze. "The boys up at Piney Creek gave it to me. No matter how low I feel or how tired or how cranky or lonely, I feel better when I look at my spoon." Now she lifted her head and slid a quick glance toward Max. "No matter what else I may have done, this spoon reminds me that once upon a time, I did one good thing."

Now Sunshine laughed. "You do lots of good things, Aunt Louise! I 'spect you always have."

"I 'spect so, too," Max said quietly, gazing at her above Sunshine's head.

Her stomach tightened, and her heart pounded against her rib cage. His expression was unreadable, but he looked at her as if he really saw her, as if his sharp blue eyes penetrated to regions others couldn't see.

Or maybe she'd been reading too many romantic songbooks.

"Well, you're both wrong," she said firmly, raising her fingertips to the heat pulsing at the base of her throat. If Sunshine hadn't been standing beside her, she might have dropped in a cuss word to emphasize her point. "I'm mean and selfish. I'm cantankerous, stubborn, and willful. So don't go hanging any halos on me." She replaced the spoon on the mantel and stepped back to admire the soft shine as she always did. "Every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost. Those are words to live by, and I do. But once," she said, her voice going soft, "I did a good thing. And I'm proud of that."

"You are so funny, Aunt Louise. Ain't she, Uncle Max?"

"Isn't," Louise said automatically. "Not ain't."

Max leaned in the archway, continuing to regard her in that peculiar, penetrating way. "Ma says she knows you don't have an extra two minutes, but she wonders if you could find time to bake mincemeat pies for Christmas Eve. She says your pies are as good as anything she can make."

That news made her smile. She'd made wonderful progress on cooking now that she had a real stove at her disposal and was using it every day. "I'll find time."

"Oh, she's mean and selfish and cantankerous, isn't she?" Max said to Sunshine. He had that sparkly-eyed, twitching-lips look. "Always seeing to her own self-interest. Just can't get her to do one thing for the family or to help out someone else."

"That's not Aunt Louise, that's Aunt Philadelphia," Sunshine said, speaking with the careless honesty of children. She beamed at them. "I can play a new song on the piano. Would you like to hear it?"

"Very much," Louise said, clearing her throat. "You can serenade me while I finish dusting and sweeping in here."

Max watched Sunshine climb up on the piano bench, then he straightened in the doorway with a frown.

"I came to tell you that Wally, Dave, and I returned to the house to get warm, but we're going out again. I spotted a cow about a mile north that looked like she was in trouble. I'll bring her in while Wally and Dave see to those sick beeves in the barn."

Louise's gaze went to the window. A blizzard raged beyond the glass. If the storm didn't blow through in the next hour, she suspected everyone would stay overnight. Already she was counting linens and pillows in her mind, trying to figure where she would put everyone. The men could make up the beds in the bunkhouse and sleep there. The women would have to share the only bed in the house. Gilly and Sunshine could climb in with her, and she'd put Livvy on the cot.

If this were a real marriage and this were really her house, she'd inform Max that the other two bedrooms had to be furnished before next winter. It would be good to have them available for emergencies.

Max coughed in his hand, then tugged his shirt collar. "I assumed you'd had that spoon for a long time. I didn't know the prospectors gave it to you." Turning his head, he gazed at Sunshine, who concentrated on coaxing music out of the piano. "I remember the schoolhouse and the first time I saw you. I thought I was on fire, and you put a cool wet rag on my forehead. I opened my eyes, and I truly thought I was looking at an angel."

"An exhausted angel with matted hair, dirty clothes, and probably wearing vomit on her boots," Louise said with a smile. She reached a finger to the mantel and touched the spoon. "The first time I saw you, you were in Dovey Watson's saloon, drinking whiskey with Stony Marks."

"That's odd." His eyebrows rose. "I don't recall seeing you before I got sick."

"There's no reason you'd remember." Tilting her head, she considered asking a question that she wasn't sure she wanted answered. "Max? I've been wondering. Why did you keep the green marble?"

Weeks had passed before she figured out what it was that he transferred from one pair of trousers to another, what it was in his pocket that he gripped like a lucky charm. Except she doubted he considered the green marble lucky.

"I keep the marble to remind me how quickly a person's life can change," he said finally. "To remind me to expect the unexpected. I keep it because it represents everything that's happened since I got sick in Piney Creek."

She nodded slowly, pulling the dust rag through her fingers. "I guessed it was something like that."

What he didn't say was the marble reminded him their marriage was only temporary. But she sensed that was also one of the functions the marble served. Eventually, he'd have his freedom.

"Did you like my new song?" Sunshine asked, turning on the bench to smile at them.

"Absolutely." Louise set aside her dust rag to applaud. "I liked it so well, I'm hoping you'll play it again."

Wally's voice called from the kitchen, and Max leaned into the hallway to say he'd be right along.

"Be careful out there," she said softly.

His gaze traveled slowly across her bosom before he met her eyes again. Butterflies exploded in her chest and banged around her rib cage. And she hoped to high heaven that he had no inkling of his power to reduce her to pudding with a glance.

"We'll be back for supper in about an hour."

Neither of them moved until Wally called again. They stood transfixed, each studying the other's tired face. Louise couldn't guess what Max was thinking, but she was thinking about the marble in his pocket.

He was right about life changing quickly. That tiny scratched marble had instantly given her a family, and a husband she was beginning to love.

Moisture glistened in her eyes, and she turned away before he saw. Oh Lord. She didn't want to love him or his family.

With a sinking heart, it occurred to her that the future held nothing but heartbreak. She could see it coming.

*

It was Max who ran into trouble. And it wasn't his heart that broke, it was his arm.

Wally and Dave brought him back to the house and sat him on the edge of the kitchen table after Livvy hastily cleared away pans and mixing bowls. "What happened?" she demanded, gingerly helping Max out of his heavy coat.

"Marva Lee didn't clear the stone fence," Wally explained. "We're going to need some whiskey to take care of this."

"Under the dry sink," Louise said. Someone, Gilly or Sunshine, threw open the cabinet doors. She kept her gaze on Max who sat white-faced, his teeth clenched, holding his arm close to his chest.

Wally took the whiskey bottle from Gilly, pulled the cork with his teeth, and handed it to Max. "If the snow wasn't so deep, Marva Lee would have broken a leg and we'd have had to put her down. And Max would have a whole lot more broken bones than he does."

"You jumped a fence?" Louise stared in disbelief. "In this weather? You dumb son of a—" Remembering Sunshine, she halted and bit her lip. The urge to yell at him sent a flood of crimson rising up her throat, and her hands curled into fists.

"It wasn't the smartest thing I ever did," Max agreed. He took a long swig from the bottle, then blinked at his mother. "Ma? You going to set this?"

Livvy threw up her hands and stepped backward. "Lord! I was never good at doctoring when it meant hurting one of my children. Wally, you do it."

"I don't know anything about setting an arm. Dave?"

"I guess I could," Dave said unhappily. Moving forward, he took off his hat, hesitated a minute, then ripped Max's sleeve up to the elbow to get a look. "That's a bad break."

Louise frowned. "That isn't so bad. When the bone's sticking out of the skin—now that's bad. But I don't see any bones sticking out." Everyone in the kitchen stared expectantly. "Oh hell. All right, I'll do it."

She pushed up her sleeves and moved next to Max. "Take another deep drink, darlin', this is going to hurt like all get out."

"Oh it's darlin', now, is it? I'm offended." Looking straight into her eyes, he took a long pull from the bottle.

"You keep drinking just as fast as you can." Bending over him, she probed the break with her fingertips, closing her ears to the hisses and gasps Max made though his teeth. "Not too bad at all. Wally, we're going to need some splints. Sunshine, help your ma rig up a sling. Dave, get Max off the table and into that end chair."

"What can I do?" Livvy asked crisply.

"You can open another bottle and pour whiskeys for everyone, starting with me."

"Here." Max thrust the bottle into her hands. She took a deep swallow, letting the heat scald down to her nerve endings. "I'm sorry, Louise."

She knew what he was sorry about. Feeding the cattle had been her first thought when he came though the door holding his arm.

"It's over now. All these weeks have been for nothing. Give me back the whiskey."

The situation demanded some serious swearing and bullying, but she couldn't let herself cut loose, not with Sunshine in the kitchen. Having a child nearby placed a severe crimp in her style.

"You are full of… horse feathers, cowboy." Leaning over him, she stared hard into his eyes. "I didn't work like a damned dog out there and freeze my butt off—excuse me, Sunshine—so we could just let those damned—'scuse me, Sunshine—stupid cows starve or freeze. And we aren't going to find a buyer for them now, that's for damned sure—excuse me, Sunshine."

He took another pull at the bottle, then pushed it back into her hands. "We can't manage it. I won't be able to lift a damned pitchfork until the end of January. Excuse me, Sunshine."

"You ain't losing those cows, Max." Tossing her head back, she swallowed liquid heat, then shoved the bottle toward his good arm. "I'll load the sled and do the forking. You can drive. Hell, the horses can practically do it alone. They know the routine. All you have to do is sit there and hold the reins in your good hand."

A chorus of voices objected, but she stared everyone into silence. "I hear what you're saying, and I know it isn't going to be easy. I don't know how I'll manage it, but I will. I can do this. Because we ain't losing those cows," she repeated stubbornly. "That's too high a price for a good man to pay! Now you,"

she said to Max. "Rest your arm on the table. Let's get this done."

She glanced at Livvy, who moved around behind Max and murmured to Wally and Dave. Thin-lipped and grim-eyed, they moved forward and each clamped a hand on Max's shoulders.

Watching her with narrowed eyes, Max lifted the whiskey to his lips and swallowed heavily before he set the bottle on the table. "Seems like you're in charge here, so what are you waiting for? Do it."

"I'm so mad at you for jumping a fence in the middle of a blizzard that I'm going to enjoy this."

She didn't. As Livvy had said, hurting someone you loved was a hard, hard thing. The only positive aspect of setting Max's arm was that she was strong and experienced, and it happened fast. She nodded at Wally, who slipped his hands down around Max's upper arm, then she pulled Max's arm straight out, doing it swiftly, pulling hard. She didn't set it properly on the first attempt, but she heard and felt the bones align on the second try. Max's eyes fluttered up and Dave caught him as he toppled over.

A body hit the floor behind her, and Sunshine cried, "Mama!"

"Give me the splints, Wally. Livvy, I need some strips to tie the splints in place."

When she had his arm wrapped and the sling packed with snow, she fell into a chair and lifted the whiskey bottle to her lips. "You folks better stay here tonight rather than risk traveling in a blizzard in the dark." She looked up at Wally and Dave. "You gents take Max down to the bunkhouse before he wakes up. Get a fire going in the potbelly, and it'll warm up in a hurry. Give me a few minutes to calm down, then we'll bring some food to you."

Dave pulled on his coat and gloves, but Wally didn't move. He stood staring like he hadn't seen her before. "I owe you an apology," he said quietly.

"No, you don't."

"Oh yes, he does," Livvy said, slapping corks back into the whiskey bottles.

"It's all right." Louise suspected she knew why Wally felt he should apologize. Someone had told Philadelphia about her being Low Down, had told Philadelphia her whole worthless life story. Early on, Livvy had probably related Louise's story to Wally, but Livvy would never have discussed her with Philadelphia . She was sure of that. But someone had.

"I haven't treated you as well as I should, Louise. Maybe I can make up for that a little by reminding you that you're not in this alone." Wally looked so much like Max tonight. Handsome. Determined blue eyes.

"You have family. Somehow we'll work this out. We'll help you feed those beeves."

The last thirty minutes had been emotional and draining. Undoubtedly, that's why her eyes swam and she had to blink hard.

"I'm not so stupid or so proud that I'd turn down a helping hand. Thank you, Wally. You, too, Dave."

She had family.

"Aunt Louise! You're crying."

"No I ain't, honey." She swiped a hand across her eyes and watched Wally and Dave take hold of Max by the ankles and under his arms and carry him outside. "We better see to your ma." Gilly was sitting sprawled on the floor, propped against the bottom of the sink cabinet. She clutched a whiskey glass against her chest and she was staring at Louise with awe and amazement.

Louise laughed. Shaking her head, she threw out her hands in a helpless gesture. "That crazy bastard.

'Scuse me, Sunshine. Jumping a fence in a blizzard! What in the hell was he thinking of? I swear, sometimes I suspect God didn't give men but half a brain. Would any of us do a damned fool thing like that?"

Livvy smiled and Gilly giggled, and then they were all laughing, great gusts of side-holding laughter that left them breathless and wiping tears from their eyes and cheeks. None of them could have explained why they laughed until they cried except they all felt better afterward.

Later, when Louise and Gilly pulled a sled laden with food down to the bunkhouse, a frozen wind drove snow and ice particles into their hair and faces. But Louise didn't feel the cold. She was warmed by the memory of Wally saying she had a family now. She wasn't alone anymore.

*

The new schedule was far from ideal. Dawn had already broken by the time Dave Weaver arrived to help with the morning feed. And since the days were short, it was dark before Wally arrived, and then he had to change out of his banker's togs and into work duds.

Max drove the sled and in the evenings he held a torch so Louise and Wally could see to work. While he stood watching, frustrated and angry, he relived the decision to jump the stone fence. Actually it hadn't been a conscious choice. He hadn't thought about the jump at all. Now his family was paying for his carelessness. And no one paid a heavier price than Louise.

When she wasn't pitching hay or feeding all the mouths on the ranch, she was shoveling a path to the barn and henhouse, chopping firewood, and milking Missy. She helped Max get dressed in the morning and undressed in the evening. She stropped his razor and shaved his face as if she'd served an apprenticeship in a barbershop. As if that weren't enough, she dragged half-frozen cows into the barn and rubbed them dry, gave them warm water to drink, and bullied them into a healthier state. Max marveled that she didn't keel over in exhaustion. He felt like she was working herself half to death on his behalf.

"What else can we do? We can't go back and change what happened," Louise pointed out. "So stop stewing around. You might as well enjoy your time off."

He slapped his book shut and shifted on the pillow to glare at her. Lamplight softened her wind-chapped cheeks and gleamed in the braid that lay across the shoulder of the cursed nightgown. But even in the mellow flattering light, deep circles were evident beneath her lashes and fatigue dulled her eyes.

"That's ridiculous. I can't enjoy anything when you're working harder than most men." Watching her chop wood or shovel a path, watching her work until her legs shook and she could hardly stand ate him up inside.

"It's not so bad," she insisted, setting aside her songbook. "We're managing. I don't mind the extra work."

"Well, I mind."

When she came up to the house after feeding the beeves and cracking ice off the stock ponds, her arms were trembling and twitched so badly that she had to steady her coffee cup with both hands to keep the coffee from spilling. Worst of all, two nights ago the temperature had fallen to fifteen degrees below zero.

Tears of frustration and determination had frozen on her cheeks before they reached her chin. He'd seen the little beads of ice in the torchlight, and he'd gone crazy inside.

"I'll make this up to you," he promised grimly. "I swear it, Louise."

"Well, there is something you could do for me. I'd sure like to have a baby," she said in a soft voice, looking down at her hands. "But with you all busted up …"

"Louise Downe McCord!" He sat up, and a slow grin replaced his frown. "Damned if you aren't turning into the temptress that half of Fort Houser thinks you are."

A sparkling glance chased the fatigue from her eyes. "I'm afraid it's finally happened. I've turned into a wanton woman."

"Absolutely debauched."

"Without shame. Too bad your arm's in a sling and you can't take advantage of my fallen state."

"My arm's busted, darlin', but everything else still works."

She had a wonderful laugh, husky and unselfconscious. "Do tell," she said when she'd caught her breath.

"There are ways to manage this where my arm wouldn't be in jeopardy."

Curiosity flickered in her hazel eyes. "If you want to elaborate on that statement, I'm listening."

"The man doesn't always have to be on top."

"Oh!" She blinked, thinking about it. "Well, nothing ventured, nothing gained. I suppose we could give that a try."

Now he laughed. She was so knowledgeable and experienced in some areas, so innocent in others. "If you're willing, as tired as you are, I'm willing, too." In fact, his body had proven itself ready, willing, and able several minutes ago. "But you have to take off your nightgown. Pitching a tent in a high wind is easier than fighting that damned nightgown."

Thirty minutes later, she slept with a smile on her lips, her head resting against his good shoulder. He needed to get up and turn off the lamps, but he knew how exhausted she was and couldn't bring himself to disturb her.

Despite what she had said the day he broke his arm, there were so many good things about Louise. If he had a herd left after this hard bitter winter, it would be because of her. To say he was grateful would be to understate his sentiments by a country mile.

Not for the first time, he decided that she reminded him of an egg. Hard-shelled on the outside, soft on the inside. She blustered and swore and slammed things around in the kitchen when she was angry. Stuck out her chin and dared the world to take a swing. But she didn't sulk, didn't pout, didn't attempt to manipulate. And although he tried, he couldn't recall ever hearing her complain. She had a remarkable ability to accept whatever life tossed her way and find something positive.

But beneath that hard, defensive shell, was a vulnerable woman who couldn't see her own worth. Others did. Even Sunshine grasped that Louise's opinion of herself was nowhere near who she really was.

And now, in the silence of a cold black night, thoughts of betrayal crept into his mind.

Philadelphia would never have volunteered to help him save his herd. If he tried for a hundred years, he wouldn't be able to imagine her pitching hay in below-zero weather with tears freezing on her cheeks, or working until she shook with exhaustion and couldn't hold a coffee cup between her blistered palms.

Philadelphia would not have stepped forward to set a broken bone. If she had remained in the room, she would have fainted as Gilly had. It was impossible to imagine her nursing a stream of men filling a schoolhouse with the stench of pus and vomit. Philadelphia would have been among the first to flee at the initial whisper of disease.

Further, he could not visualize Philadelphia ever throwing off her nightgown and her inhibitions as Louise had done tonight. Philadelphia would always be the rigidly delicate and modest lady who submitted and endured and participated as little as possible because joy and enthusiasm in the bedroom would damage her dignity and self-image. He couldn't know for certain, but he suspected Philadelphia would view sex as a manipulative tool, dispensing her favors as a reward or in exchange for favors granted.

Frowning, he stared at the icy frost patterns laced across the windowpanes, and he remembered Philadelphia ridiculing Louise in front of Sunshine, and again in front of the family at dinner. He remembered countless incidents of pouting lips and copious tears and a stamping foot. Oddly, he did not remember laughter in their relationship. He remembered his goals and her goals, but no common goals or shared viewpoints.

What on earth had drawn them together?

Lowering his head, he rubbed his fingertips across his forehead. Damn it. How could he criticize the mother of his child? How could he justify such disloyalty? Without the intervention of one green marble, it would have been Philadelphia sleeping beside him now. It would have been him fastening a stiff starched collar around his neck and riding into the bank every day. Not so long ago, that's what he had believed he wanted.

But his worst betrayal came when he smiled at Louise and realized with sudden guilt and astonishment that he could love her. And when he understood that he respected and admired this unusual woman, and he genuinely enjoyed her company.

When these insights occurred, his mind instantly backed away and his thoughts shut down. What kind of bastard would love one woman while another carried his child? Tar and feathers were too good for such a man.

And there was the fact that Louise would leave him once she became pregnant. This was their agreement. Through trial and error and compromise they were managing to live together and doing it successfully, in his opinion. But she'd said nothing to indicate that anything had changed. Their agreement held.

He gazed down at the top of her head and the curve of her cheek. Studied her work-roughened hand rising and falling on his chest. Once he had believed that smooth pale hands with manicured nails were beautiful. Now his eyes had opened to the aching beauty of bruised knuckles, blunt nails, and callused palms.

If it hadn't been for Philadelphia and the child she carried… if he and Louise hadn't agreed their marriage was only temporary…

But he would never know what might have happened. He could allow himself to respect Louise and enjoy her company, but he could not permit his regard to deepen into anything more than admiration and esteem. Not when mere months ago, he would willingly and happily have married someone else. Not while that someone else grew large with his child.

Fullepub

Fullepub