The Eight-Thirty From Waterside to Downtown Remy

Claude

Contrary to popular belief, the Lord of Mushrooms wasn’t a fun guy. He was, in fact, a miserable, cantankerous bastard who was sick of everyone’s crap, and if he had to listen to one more “There’s not mushroom in here” or “I didn’t like you at first, but you’ve grown on me” comment, he was going to lose his shit.

That was me. I was the Lord of Mushrooms.

I’d inherited that title just this morning, though I wasn’t exactly in a rush to use it. Didn’t need any more reasons for folk to label me a pretentious bastard.

Claude Stinkhorn, or Mr Stinkhorn would be just fine.

I hadn’t always been this guy—the grumpy asshole U-train conductor—though from what I could remember of my adolescence, I’d always been somewhat asshole adjacent.

There was this one time, however, about three years ago, when I’d made it almost twenty-four hours without grumbling. I’d won the U-Rail’s Employee of the Decade award. Honestly? Best day of my life. I’d worn my fanciest suit, caught the underground train to the ceremony, and was presented with a glass trophy and a pair of beautiful mushroom-shaped, twenty-four-carat-gold cufflinks. Afterwards, I ate salmon and cream-cheese canapes, met the company directors, caught the early train home, placed my award on the mantel and my cufflinks in my safe-place drawer, and worked on my puzzles.

All in all, a perfect evening. I’d even smiled—twice.

The most enjoyable part was riding the train but not working it. Somebody—Patricia probably—had taken over my shift for once, so I got the full immersive experience of every business-type on their daily commute.

Who said dreams had to be big? I loved my job, I guessed. I loved the city. Why would I want anything more?

Once again, I found myself riding the train sans ticket machine. Wearing the same suit and my fancy mushroom cufflinks, drinking a mediocre chai tea latte purchased from the onboard restaurant cart, and looking—hopelessly—for a free seat.

Because it was not Thursday, six thirty p.m. like last time, it was Tuesday morning, shortly before nine. Rush hour. And the train was chock-full of office-wallahs and marketing execs and uni students and construction-types. Folk of every gender and species. Human, mythic, undead, demigod, et cetera. I knew it would be, but I’d had no other choice.

As per, the middle carriages had standing room only, so against my better judgement, I wormed my way to the caboose and peeped through the final porthole window. I pulled myself into the narrow gap, sucked in my stomach, and held my breath.

He was there.

Urgh. Of course he was there.

He always caught the eight-thirty train from Waterside to Downtown Remy. Always sat in the same seat, right at the back of the very last coach. Always had the same drink and snack set up on the table—a black coffee and something that smelled suspiciously like a kilo of butter wrapped in flaky pastry. Stupidly flaky pastry, I might add, that blew everywhere.

I stole another peek through the glass, flattening myself and hiding against the wall of the carriage. Something—irritation probably—bubbled in my stomach. Maybe I could stay here in the gangway next to the toilet until my stop? It wasn’t a long ride, and I was very accustomed to surfing the carpeted floors of the carts.

Anything to avoid sitting near him.

I knew only four things about this guy, but that was four too many.

Thing number one: his name was Sonny. Or at least, Sonny was the name he gave me every morning when I sold him his ticket, and every evening on his return journey. He always waited until he was on the train to buy it from me—never bought it at the station like everybody else—I think simply to annoy me. To deliberately make my day fractionally more complex.

Thing two: like me, Sonny was fae.

But where I was shroom fae—harmless, kept myself to myself, an essential component of a wider and very important ecosystem—Sonny was a decidedly more nefarious type of fae. A magpie fae, of the Corvidae fae genus. Known for their kleptomaniac tendencies, the inability to keep their hands in their own pockets, and an overarching obsession with anything shiny and not belonging to themselves.

Thing three, and this was super unfortunate: Sonny was absurdly attractive. Absurdly.

Like, once you’d been made aware of his presence, you’d be hard pushed to avert your gaze from him. His face was a warm, dirty street lamp, and my eyes were stupid, stupid moths.

It just had to be the way, didn’t it?

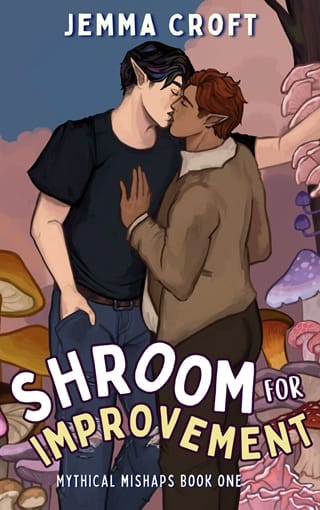

He was tall, approximately seven inches taller than my six feet of height. Lean, bordering on scrawny, with the telltale magpie-pale skin and black hair that looked as though it’d been painted with gasoline. If you studied him closely enough, you’d see iridescent stripes of forest green, midnight blue, and eggplant purple in his hair. Which I definitely never saw, because I definitely never looked that closely. His face was nice, I supposed, if you dug that whole “conventionally attractive fae” bullcrap. His nose was altogether too straight, his cheekbones would cut diamonds, and his pointy ears were, well, pointy. His brows were two perfect, thick black lines that seemed to move independently from the rest of him, and his huge dark eyes were a little on the buggy side. And those lips... well, the less said about those lips, the better, really.

A mesmeric oddity.

And definitely not my type. And not the type of person I’d choose to associate with outside of work.

Not that I associated with anyone outside—or inside—of work, but still.

I peeked through the glass again. Sonny had stretched his impossibly long legs out and propped his grubby, trainer-clad feet onto the table, getting street crud all over the vinyl. His nose was buried in an ancient-looking leather-bound book. He wore headphones, and a T-shirt with a cartoon sunglasses-wearing otter driving a convertible car. From where I was standing, I couldn’t make out the text on the shirt, but it didn’t matter, I’d seen that one before, several times. It read: Grand Theft Otter .

Ironic.

Those were the first three things I knew about Sonny—if that was even his real name. He’d probably stolen it like everything else. Frankly, I was better for not knowing. Did he have a job? Or was he a professional grifter? Did he have a family? Or had he stolen someone else’s? It was anyone’s guess.

Even still, I didn’t want him to see me. Because the fourth and final thing I knew about Sonny...

That magpie fae was one loquacious bastard.

“’Scuse me!” A dragon shifter wearing a polyester business suit barged past me. He clenched his abdomen with both hands and flung the door to the train’s toilet open, then slammed it shut behind himself.

I eyed the door of the lavatory. I could stay here, and wait for whatever horrors might bleed through the gaps where the door didn’t fully seal itself against the panelling. Or I could take my chances with him , and whatever gods-awful conversation he might attempt to throw at me.

“Oh, hell,” the dragon shifter whimpered a moment later, echoing my exact thoughts.

There was no other option. I held my breath, and on tiptoes, I slid into the caboose carriage. Sonny glanced up from his book, nodded an indifferent acknowledgment in my general direction, and returned his attention immediately to its pages.

My shoulders dropped in relief, and I folded onto the seat next to the window, keeping him in my peripherals because, well, nobody was stupid enough to turn their back on a magpie fae.

I’d gotten away with it. He hadn’t realised it was me—

“Claude?” Sonny removed his legs from the tabletop, pulled his headphones off and turned his book upside down, open to whatever page he was on.

I’d never told him my name, and it said only C. Stinkhorn on my badge. He must have asked Ken or Pat for it at some point.

“I didn’t think I was going to see you today,” he said. “I had to buy my ticket from someone else. Patricia? She’s nice, isn’t she? She showed me pictures of her daughter’s wingball team. Cute.”

I blinked at him. Patricia had said a grand total of four words to me since I’d met her six years ago. “You must be Claude.” That was it. Not spoken a word since. Which I liked. And appreciated. And was why I’d probably rank Patricia among my top five favourite colleagues.

“Almost didn’t recognise you without your uniform,” Sonny continued, obviously having gleaned nothing from his time with Patricia. “Those are some... serious looking civvies you’ve got on there. Did someone die? Or do you always dress like a fusty librarian when you’re not working?” He laughed at his own non-joke, evidently expecting me to join in.

“Yes. To both things,” I said, totally not relishing the fleeting foot-meet-mouth moment that played over Sonny’s face.

Someone had indeed died. My father, actually, though I seldom saw the man. Wouldn’t even remember what he looked like if it weren’t for the generic shroom fae appearance that graced us all. The same light brown skin, same rust-coloured hair, and the same pale grey freckles wherever the sun kissed our skin, especially on our noses and the tips of our pointed ears.

Angus Stinkhorn. Famous explorer. On a perpetual quest to discover... gods knew what. New glamour, new flora and fauna, new women? Maybe all three. In fact, this was how he’d met my mother. In a small, middle of nowhere town in the Kingdom of the Fae. He’d paused his expedition just long enough to spread his spores, and was gone before I’d been born. He’d written to me a few times—spelled my name wrong more often than not—and had visited once per century, but otherwise, I hadn’t heard a peep from him.

Then, this morning I’d received a letter, hand-delivered by a spritely young fae with leaves in their hair, berries around their neck, and what seemed to be an entire holly bush spilling out of their sandals.

I’d read the letter, immediately changed out of my housecoat and slippers, and caught the first U-train into town.

So, the second part of Sonny’s question-slash-observation was also true. I didn’t mind the slight because yes, given the choice, I would always dress like a fusty librarian.

People just didn’t understand proper style these days. With their threadbare jeans, and their knees and butt-cheeks hanging out, and their midriffs all... midriffing. Give me brogues over scruffy canvas trainers any day. Waistcoats over exposure-induced hypothermia. Real wool coats over accidental public indecency.

“Someone died?” Sonny said, bringing his hand up to his mouth. His fingernails were painted forest green. I’d forgotten what we were talking about. “Shit, sorry, I didn’t mean to... Were you close? To the person, I mean. Are you going to the funeral right now?” He brandished his decorated hand towards my suit.

Why didn’t this guy ever stop talking? I figured the quickest way to shut him up was to give him what he wanted. Or some semblance of that. “My father. No, we weren’t close. No, I am not going to his funeral.”

Sonny opened his mouth to speak, evidently decided better of it, and snapped it shut again.

Good. I win.

Somebody had left a newspaper on the empty seat beside me. I picked it up, opened it at random, cleared my throat, and pretended to read the article, but it was merely shapes and letters and breakfast-grease-smudged ink.

Sonny sat back, ran the fingers of one hand through his silky raven hair, and drummed the others against the vinyl tabletop. “You’re a shroom fae.” He grimaced, muttered “why?” to himself, and rolled his eyes to the ceiling.

I didn’t let mine appear to leave the newspaper. “And you’re a very observant chap.”

No fae could lie. That was common knowledge. Certain types of fae could bend the truth more than others, and we could all dance around it, but sarcasm was different. It was something I’d worked on my entire life and practised to a fine art, yet my light-fingered companion obviously failed to grasp the concept. Another of my talents gone to waste.

“It’s just, you don’t see many shroom fae these days.”

“No, you don’t,” I replied.

Sonny chewed over his next words. I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of my attention. “They’re fascinating, really. Shroom fae. I hope you don’t mind me saying—”

“I do—”

“Your glamour is so interesting.”

“It is not. It is unexceptional. Commonplace. The same as every garden-variety fae.”

Every fae had some grasp of basic glamour. The ability to influence the elements—fire, wind and water—that was standard. Our hearing, sense of smell, and eyesight were better than a human’s, but not excessively so.

Yet, what I didn’t have were type-specific glamours. Magic that only shroom fae wielded. A lot of fae had unique gifts that belonged only to their genus and were passed down throughout generations. For example, a nymph had some sort of super sex power. A shadow fae could shapeshift. A winter fae could freeze a man with a flick of the wrist.

Some fae could heal. Some were exceptional in battle. Some were naturally gifted leaders. Some even possessed the ability to see the future.

I had nothing. Nothing to set me apart from my brethren.

And anyway, even if I had any special type of glamour like mind reading or tap dancing, I doubted I’d be any good at them. I’d always been a bit... shit, with magic. Luckily, folk like Sonny would never have to know how shit I was.

“But you can communicate with plants,” Sonny said, as though reading my thoughts and trying to prove me wrong.

I shook my head. “I cannot even keep a houseplant alive.”

“You have uncommon healing powers?”

“I’ve had a perpetual cold for eighteen months now.”

“You have, like, incredible anti-aging magic?”

My laugh came out of my nose. A snort. “I look every bit my five hundred and ten years.”

“Mmhmm.” Sonny trapped his smile between his teeth. “In human years, you look no older than fifty—” I gasped. “Forty-five, then.”

“And you appear to be twenty.” I meant it as an insult, but the bastard smiled.

“Three hundred and sixty-six... ish, but thank you. You want to know my secret?”

I deliberately and noisily crumpled the newspaper, then straightened it with a flick of my wrists. “I do not.”

“My night cream contains mushroom extract,” he said.

Unbidden, images of Sonny at bedtime, rubbing crème de shroom into his cheeks, flashed through my mind. Did he wear pyjamas? Or did he sleep shirtless? Or completely nu—

Nope. Shutting down those thoughts immediately.

“Also,” he continued, either unaware I had no interest in pursuing the conversation or not in the slightest bit bothered. “Oat jizz, uh, shit—” The tips of his ears grew pink. “Juice. Oat juice. There’s, uh...” He blew out a breath. Surprisingly minty, given his half-drunk travel mug of black coffee on the table. “There’s like, an enzyme in oat that when mixed with water, restores your skin’s natural microbiome.”

I lowered the paper and gazed at him for two, three seconds. A response formed at the back of my throat. I willed it to stay there, not to slide along my tongue like it was desperately trying to. He was only being nice. Or... whatever he was attempting to be.

Don’t say it, Claude.

“So...” Do not say it. “Tell me, which department store did you liberate that product from?”

Why, Claude, why?

Why did I have to be that way?

“Ah,” Sonny said, sitting back in his seat again. He was still smiling, but now it was tight-lipped, and his eyes were no longer crinkled at the edges. “I see. Because I’m magpie fae, it automatically makes me a criminal?” He raised his eyebrows—a challenge—and I felt the tips of my ears heat.

I should’ve apologised to him, said sorry for jumping to conclusions. He was just an innocent victim of a terrible stereotype. But the thing was, fae couldn’t lie. So even if I wanted to apologise, I wouldn’t have been able to. I wasn’t sorry I’d offended him.

Instead, I went with, “You made false assumptions about me based off my type.” They’d been positive false assumptions, but still.

And let us not overlook that this may have all been part of some greater swindle he was working. Disarm me, and when my defences were down, swipe my wallet.

Sonny sighed, folded his arms over his chest, unfolded them, picked at the peeling vinyl on the tabletop. “You’re right. Forgive me.” He scratched at a spot on his sternum, directly above the otter’s head. It really was an abomination of a T-shirt. Just the worst. But I allowed myself one more second to catalogue how nicely the sleeves hugged his slender biceps, before I returned once again to the black and white photo of the newspaper.

Outside the windows, two stations whizzed by. Sonny had finally cottoned on to my distaste for conversation. Next stop was Downtown. He always got off there. To do what? Who knew? No doubt inner-city Remy was the choicest spot for most petty thieves to operate. Ordinarily, I would continue with the train another twelve stops to the end of the line, but today, I was also alighting here.

I got to my feet early, hoping to put at least one passenger between Sonny and myself, but the millisecond I stood, he did too. Like he’d been waiting for me, watching me like the beady-eyed corvid he was. A smile ticked the corners of his mouth. He nodded and held out a hand, which translated to after you .

Together, we moved into the gangway. I leant my back against the wall, and tried not to make eye contact, or breathe in the scent of him. Incense and clove. At once smoky and clean, and also kind of mossy. It was a weird scent. And it annoyed me that it suited him so well.

I had the bizarre urge to strike up a conversation. To ask him where he was heading, what his plans for the day were. Who even was I? But I’d learned my lesson. I shook the thought and bit my tongue.

“Hey.” Sonny spoke to his scuffed-up footwear. He scratched the back of his head. “So, I don’t know, I get the impression you’re, uh, not into this... but I was just wondering, if, uh, someday, you’d like to get cof—”

The train reached the station and screeched to a seemingly abrupt stop. The carriages and their contents pitched sideways. Being completely used to it, I braced myself against the gangway wall, but Sonny flew forward, straight into me. My arms shot out to meet his shoulders and buffer the impact, but he fell between them, colliding with my chest like we were hugging. I was acutely aware of all the parts of our bodies that were touching.

All. Of. Them.

His hands were on my waist, then my hips, and shit, was I breathing him in again? Was I closing my eyes against the firm press of his torso?

I pushed him off, and he offered me a pink-cheeked smile that was definitely not cute.

Wait a second . . .

I patted down my coat pocket—plunged my hand into it, making sure my wallet was still there—and released a breath.

Sonny raised an eyebrow. “I thought we’d moved past harmful presumptions?”

Shit. I turned my face so he wouldn’t see it flame with embarrassment. “Forgive me.”

He was right. I should know better than to judge. I’d known—sort of known—this guy for three years, and though he was intolerably vociferous, he’d never caused a problem on one of my trains before. To my knowledge, he’d never actually committed a crime under my watch. Gods, what was I thinking? I was an asshole.

The door slid open, and I jumped down onto the platform.

Sonny followed me. “You’re forgiven,” he whispered, still for some gods-forsaken reason all up in my personal space. “And it was your cufflinks I went for, not the wallet.” He grabbed my hand in his and pressed a tiny golden mushroom pin into my palm. “Have a good day, Claude.”

Before I could respond, the swell of bodies carried us both separately from the platform and out of the station, dumping me into the bright April morning. Buildings rose around me like shining, jagged claws, car horns blasted, music blared from windows and shop doorways, people yelled into their phones and barged past me, traffic lights bleated, sirens wailed, and the fumes and dirty city stink hit me all at once.

Home.

I stared down at the fingernail-sized gold mushroom in my palm and stroked my shirt sleeves.

He’d removed both my cufflinks, I realised.

And only returned one.

Fullepub

Fullepub