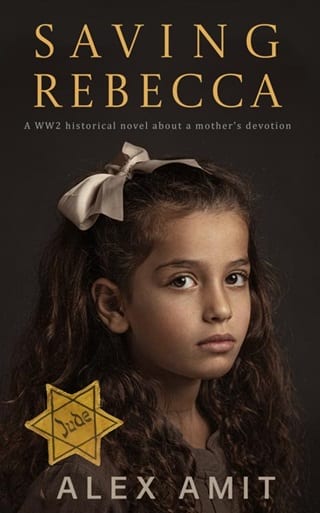

5. Autumn

Chapter five

Autumn

"Mommy, when will my beautiful dress arrive from Paris? And my book, too?" Rebecca asks me a few days later while we stand by the fence and look at the houses in the distance.

"In a few days," I reply quietly as I place my hand on the barbed wire fence, feeling the coolness of the metal. I notice a few people walking between the houses. I long to trade places with them and not be confined to this cage.

"But you said that a few days ago," Rebecca continues to ask.

"Yes, and it hasn't been a few days yet," I continue watching a woman in a dark dress walking and pulling a cow tied with a rope behind her. She leads her cow leisurely until they both disappear into one of the yards. I imagine the taste of fresh milk on my lips.

"But you promised," Rebecca insists, "and you always say that promises should be kept."

"That's right, the suitcase with Sylvie's book will arrive," I stroke her hair. Since we got here, I haven't been able to shower her, and her hair is disheveled and messy. "Promises must be kept," I look back at the houses outside and the road leading to Paris. "You also promised to take care of us," I whisper. "You promised we would follow you to Madrid."

"What?" Rebecca asks me.

"Nothing," I notice a rumbling bus coming from the road toward the camp. In front of it is a black police pickup truck leading the way. A few policemen come out of the barracks and watch its arrival. I think I can spot the policeman with the glasses among them. I think his name is Mathéo. That's what his friend called him. "Sweetie, let's go back," I say to Rebecca. I don't want to be at the gates when the people get off the bus and walk in, not knowing they have arrived at a prison.

"Can we stay a little longer? Please?" She looks up at me.

"Only for a few minutes."

"I promise," she says and grabs the wire fence, her little fingers wrapping around the metal wire.

The bus stops in the parking lot with its engine still running for a few moments, filling the air with the pungent smell of burnt gasoline. I breathe it eagerly; I miss the smell of the city so much.

"Mommy, he opened the door," Rebecca points, placing her hand over the fence. I glance sideways at the guard, worried he might do something to her, but his attention is on the bus parked outside the gate.

The policemen who emerged from the barracks surround the bus; their rifles slung carelessly over their shoulders. But I don't think they need their rifles. No one can escape now; it's too late.

"One, two, three..." Rebecca counts the people who get off the bus, holding their suitcases and looking around .

"This way," one of the policemen shows them the open gate waiting for them, and another policeman shouts at them to start walking inside. I look at the policeman with the glasses. He stands motionless and watches the people walking into the camp, not rushing them in like his colleagues but also not helping the elderly woman with her long coat, to which her yellow badge is sewn. She's struggling to walk from the bus to the gate. What kind of man is he? Why did he choose to work here?

"Everyone got off," Rebecca whispers, and I hear disappointment in her voice.

"That's right," I reply when the bus driver starts again and closes the door. "Let's go back."

"And no one brought my suitcase. Can I stay a little longer?" She asks sadly.

"No, it's late. The sun will set soon."

"But maybe another bus will arrive."

"There won't be another bus today," I tell her. "They drive in together."

"Maybe there will be another bus," she insists, "and with it our suitcase." Her grip tightens around the barbed wire.

"Buses are not allowed to travel at night, and it's almost dark. Maybe tomorrow the bus will bring the suitcase," I pick her up. I don't want to tell her that our suitcase will never arrive. "Let's go; it's time to keep promises," I tell her, although it's not her promise I'm referring to.

"Charlotte, do you have any paper and pencil?" I ask her when I enter the room. She is facing away from me and quickly tried to hide something under the cardboard she sleeps on. "What are you doing?" I ask her .

"Nothing," she says, turning to smile at me. "I think I have some. Why do you need it?"

"I want to write a letter. I know there's no mail, but I have to write one," I say as I take Rebecca off my hands and look at Charlotte's piece of cardboard. What is she hiding from me?

"This is all I have," she says apologetically, taking a small, crumpled piece of paper and a pencil from her bag and handing them to me. "Who are you writing to?"

"I want to write to my husband to come help us. He must do something," I say, looking at the clouds outside as they cover the last rays of sun.

"What exactly will he do?" She asks, somewhat mockingly.

"I don't know," I hesitate before answering, "but he will find a solution. He always does. He is a respectable businessman."

"A respectable businessman who left you in Paris?"

"He went to Madrid a month before the Germans started the war. He didn't intend to leave us behind. The plan was for us to join him and then continue to America," I explain as I place the paper on the floor and begin writing.

"He's your husband, and you know him better than I do, so I probably shouldn't interfere," she says. "But he won't come here to help you."

"He must. He told me to trust him, so I must trust him," I respond, trying to focus on writing the first words.

"No one will come from Madrid back to Nazi Germany to save you, even if you write him thirty letters."

"Mommy, are you writing Dad a letter?" Rebecca interrupts our conversation.

"Rebecca, what did I tell you about interrupting adults' conversations?" I turn to her, my tone stern .

"Sorry," she steps back and leans against the wall, her fingers fiddling with the simple ribbon tying her hair. I think she's about to cry.

"I'll finish talking to Ms. Charlotte, and then you can join the conversation," I tell her. Why is all this happening to me while my husband escaped? "He's going to do something; he has to," I whisper to Charlotte, trying to keep Rebecca from overhearing.

"You need to understand that the only ones who can do anything here are you and the police who guard us," Charlotte whispers back. "They can organize and arrange things if you have a way to pay them."

"They're police officers; I don't trust them."

"There's also Mr. Charpak," she adds.

"Who's Mr. Charpak?"

"I haven't met him, but I've heard of him. He's stuck in here with us. He was a trader in Paris, in markets you and I wouldn't go to, if you know what I mean," she smiles slyly. "Now he's a trader here. There's always a demand for traders, even inside a detention camp."

"And how do they get paid?" I ask her, feeling my stomach churning. I think I know the answer.

"French francs, German money, cigarettes, he and the officers accept everything, even that kind of payment," she points at her breasts.

"Mommy, what's ‘payment'?" Rebecca asks.

"Never mind," I reply. For a long time now, she has been hearing more than she needs to hear. "Mr. Charpak can send a letter for me? "

"I think he can do anything, if you're willing to pay the price," she approaches me and whispers, so Rebecca won't hear. "But it's a waste of your money; no husband will come to save you. It's time you start trusting yourself."

"Where can I find him?" I ask her as I bend down, continuing to write on the floor.

"People like him are like stray cats; when you look for them, you find them."

"Can you watch over Rebecca for a few minutes?" I ask her when I finish writing. I'm not like Charlotte. I have a husband. I have someone to trust. I also have a way to pay him.

"Excuse me, where can I find Mr. Charpak?" I ask as I walk down to the yard in the center of the building. I turn to a man wearing a Homburg hat and a brown suit, which is covered with mud stains.

"I don't know," he answers, but he seems to be lying.

I turn to the group of men playing pétanque in the center of the yard, but they also don't know, so I continue to walk around the yard asking people.

"Why do you need him?" A woman asks me. She is about my age and leans indifferently against the wall near one of the entrances.

"He's a trader, isn't he?" I ask her.

"Yes, he's a trader, if you have something to trade," she replies, scanning my body, her gaze lingering on my chest .

"I need something from him," I say, crossing my arms to hide my hands.

"Entry three, second floor, you'll find him there."

"Thank you."

"You're welcome," she replies as she lights a cigarette. "What are we women here for if not to help each other?"

I thank her again and walk away. I have another way to pay him. If the rumors are true, he can send my letter to my husband.

The stairs leading up to the second floor are similar to the ones in our entry, but here, blankets and fabric cover the apartment entrances, offering privacy.

"Who are you looking for?" Asks a young man leaning against the wall in the stairwell on the second floor. He's smoking a cigarette and wears a light button-up shirt, suspenders, and a beret.

"I'm looking for Mr. Charpak," I answer, trying to get used to the cigarette smoke that fills the stairwell.

"What do you want from him?"

"I need something from him," I say, standing before the young man and feeling tense. He also scans my body, his eyes examining my face and then moving down to my chest and hips.

"Mr. Charpak, someone is looking for you," he calls into the room, moving aside the floral sheet covering the doorway.

"Let her in," someone replies from inside, and the young man signals me to enter.

Inside the smoke-filled room, an upside-down wooden crate serves as a makeshift table. Several men sit on upside-down wooden buckets, playing cards around it .

"What do you want?" One of the men asks, turning to me. He wears a wrinkled blue jacket and has a cigarette in his mouth.

"I'm looking for Mr. Charpak," I answer, feeling embarrassed as all the men stare at me.

"What do you want from him?" Asks the man in the blue jacket. Is he Mr. Charpak?

"I need something," I say, raising my chin.

"I'm out," a big man, almost bald and about fifty years old, says to his friends. He puts his cards on the table, then stands up from the improvised table and approaches me. He wears a blue workman's shirt and plain blue trousers secured with a brown belt. "What do you want?" He holds my arm and guides me to a side room. In the room, he stands uncomfortably close to me, and his breath reeks of cigarettes.

"I was told you could arrange things," I say, looking up at him.

"People need things. We are Jews, and we help each other. It's a mitzvah," he says with a smile I don't trust. It makes him seem like a fat cat eyeing its prey.

"I need to send a letter to my husband in Madrid," I show him the paper I'm holding. Saying the words 'my husband' gives me courage.

"How much are you willing to pay for the delivery?" He touches the folded paper in my hand.

"I have this," I take out the remaining money in my wallet and the food coupons. They hold little value here.

"I'm a merchant, not a beggar," he laughs, revealing yellow teeth in the weak light. "Do you know how many hands this letter must pass through to reach Madrid? And each of them will want their share."

"So what do you want as payment?" I try to distance myself from him in the small room. The rough concrete wall rubs against my back. I consider my hidden gold coins. Should I use them to pay for the letter?

"You can give me what women know how to give," he steps even closer. His hand reaches out and touches my waist. I struggle to breathe, and my body tenses.

"I'm a married woman. You know I'm not allowed to do such a thing," I whisper.

"I don't see that God is watching over us here," Mr. Charpak looks up at the ceiling. "But if it doesn't suit you," he steps back from me, "bring me some clothes. Winter is coming, and people will pay a lot for warm clothes. You can decide," he chuckles, "a letter in exchange for a few minutes of warmth with a man who isn't your husband, or giving up clothes for the winter. That's how it is in Judaism; God has always presented us with difficult choices."

"I'll think about it," I say, feeling my face flush. "I'll be back," I turn and hurry out of the small room into the larger space where the men continue their game. I'll get him his clothes. I'll find a way to pay him. But on my way down the stairs, I feel the cool breeze and think about the approaching winter.

"Charlotte, do you have a knife?" I ask as I walk back into our room. I need to hurry; soon the curfew will begin, and it will be forbidden to be outside.

"Why do you need a knife? Did you send the letter? "

"No, I didn't send it. I wasn't willing to pay what he wanted. I want to open this." I hold the stranger's suitcase. "He won't arrive."

"And what about our suitcase? It won't arrive either?" Rebecca stands beside me. What should I say to her?

"Sweetie, they decided to switch, and we received this suitcase instead of ours," I tell her as I take the knife Charlotte handed me and try to break the lock.

"What about my green dress and my book?"

"Maybe there's a dress and a book in here too," I say, giving her a quick glance before returning to the lock. "Perhaps it's a better suitcase with surprises," I tell her.

"Okay," Rebecca nods and approaches the suitcase. She watches my hand, holding the knife, as I struggle to open the lock. "Maybe there's a Sylvie teddy bear and chocolate inside," she suggests.

"Maybe, we'll see," I whisper to myself, hoping she won't be disappointed when she discovers there isn't a Sylvie teddy bear and chocolate. I hope I won't be disappointed to find there are no warm winter clothes.

"Try using a stone," Charlotte suggests.

"Rebecca, go down to the yard and get me a stone," I tell her without turning around. I hear her running as she descends the stairs.

"Is it okay that you sent her all by herself?" Charlotte asks after a moment.

"I can't watch her all the time," I reply, but then I go to the window and look out into the yard. Rebecca runs across the yard, picks up one of the stones used by the pétanque players from the empty yard, and hurries back.

"I brought it," she says, entering the room after a moment, panting. She hands me the stone and stands beside the suitcase, waiting for her surprise. I hold the knife close to the lock, and Charlotte strikes it with the stone until the lock breaks, making a metallic sound.

"Let's see what's inside," Charlotte whispers as I open the suitcase.

"A jacket," I say, pulling out a men's blue jacket.

"And two pairs of pants," Charlotte lays them out on the floor.

"And underwear."

"Is there a green dress?" Rebecca asks, hopeful.

"And good leather shoes," I take them out of the suitcase. "I need shoes; mine are falling apart."

"They'll be too big for you," Charlotte points out.

"It's better than worn-out shoes."

"Mommy, is there a green dress, a book, and chocolate?" Rebecca bends down and takes out the remaining clothes from the suitcase, searching under them.

"No, there isn't a green dress, a book, or chocolate," I say to her in a disappointed tone. "Again, they got the suitcases mixed up." What else should I tell her?

"They keep mixing them up," she whispers, and I see she's about to cry.

"You need to tell her the truth," Charlotte whispers to me in French. "She needs to grow up."

"She's five and a half years old," I whisper back. "She hasn't played with other children for a year. In Berlin and Paris, she was a Jew who wasn't allowed to enter playgrounds, and here, she's bullied because she's German. She has very little childhood left to hold on to."

"So, what will you tell her?"

"You know what?" I hug Rebecca and stroke her hair. "Tomorrow, we will go back to wait for the bus. I will talk to the person in charge of the buses to see what happened to our suitcase."

"Are you crazy?" Charlotte whispers to me.

"I'm a mother."

"And what will you do?"

"I'll be fine. Is there anything you need here?" I gather the stranger's clothes from the suitcase and set the shoes aside. They are more valuable.

"These," she takes two tank tops.

"I'll be right back." I collect all the other clothes and shoes. "Charlotte, can you watch Rebecca for a few minutes?"

"Would you give up all these clothes to send a letter?" She asks me.

"Please, it's important. Just stay with her for a few minutes," I answer and leave the room, holding the clothes in my hands. I have to do this; I won't regret it.

"Is this what you're offering for the letter?" Mr. Charpak approaches me a few minutes later in the side room. He feels the fabric of the stranger's pants and shoes in his hands. "I thought you'd changed your mind. Where did you get them? They're men's clothes." In the other room, I hear the men playing cards and raising the stakes.

"They are my husband's," I reply quietly and try to stand tall. He mustn't sense my fear .

"The one you're sending the letter to?" He laughs mockingly. "Okay, give me the letter. I'll see what I can do."

"No," I reply, taking a deep breath. "I want something else."

"What?" He watched me closely.

"A coat for a girl and a pair of women's shoes for myself."

"You're giving up the letter?"

"The letter will wait," I push the clothes into his arms. "I want a warm coat for the winter for a girl, and a fabric to seal a window against the rain."

"As you wish," he takes the clothes and steps back. "You must know that the Germans have been advancing in Russia for months. At this rate, they'll rule the world, and we will have to get used to it. I can't promise I'll be able to send the letter in the future."

"A warm coat for the girl, shoes for myself, and fabric for the window," I respond, hoping I made the right decision.

"Let's go back. It's late," I say to Rebecca a few days later. The sky is cloudy, and it will rain soon.

"But Mommy, the bus hasn't arrived yet," she continues to stand there, holding the barbed wire fence with her small hands.

"Maybe it won't come today. Maybe it went to a different camp today."

I look at her. She's lost weight in the last months, but at least she has a coat to keep her warm. I shiver slightly in the autumn breeze, and I reach out to touch the hidden gold coins in the dress. Soon I'll have to decide – a coat for me or food for her.

"Will the bus give our suitcase to someone else?" She turns and looks at me with a concerned expression.

"No, of course not," I say, placing my hand on her cold palm that clutches the wire fence. "Your suitcase belongs only to you. We'll wait a few more minutes; if the bus doesn't come, we'll go back and return tomorrow."

"And if the bus doesn't come tomorrow?"

"If it doesn't come tomorrow, then we'll ask the hunters when it will arrive," I answer without thinking. I hope the bus won't come soon or at all, as the camp grows more crowded each day. Queues for food distribution and the water tap grow longer, as do the arguments and quarrels among the people who have nothing to do but gossip and fight.

One of the policemen standing near their barrack begins to approach us, and I instinctively step back. But then I see another policeman approach him and whisper something, prompting the first one to turn back while the other walks toward us.

"Let's go, Rebecca. We need to leave," I say, picking her up in my arms. The approaching policeman makes me nervous, even though they are French and not Nazis. I can't forget what happened during the muster in front of the Nazi officer.

"But, Mommy, you promised a few more minutes."

"Those minutes have passed," I tell her. The policeman reaching us is the one with the Windsor glasses, and he signals us to stop. What should I do? I feel the urge to turn and blend into the crowd behind us. But I have to stand still. These are the rules here .

"Do you need anything?" He asks, standing on the other side of the fence.

"No," I respond, keeping my eyes on him. I can see his brown-green eyes through his round glasses.

"Then why are you standing by the fence and looking outside?"

"We're looking at freedom," I reply, regretting my words as soon as they leave my mouth. What was I thinking being so rude to a policeman who could punish me? I have to thank him for saving my life when I wanted to speak with the Nazi commander.

He remains silent, his eyes fixed on me. I slowly lower my gaze, observing his perfectly ironed uniform, the embroidered ranks on his arm, the rifle strap hanging over his shoulder, the leather belt around his waist, and the pistol placed in a shiny, oiled leather holster. I must apologize; I have a child to care for .

"I apologize, and thank you," I whisper to him, standing with a humble look. I know how to stand like this since the word 'Jew' became a curse, and we were forced to embroider the yellow Stars of Life and Death on our clothes.

"Join the others. It will rain soon," he says after a moment.

"Yes, sir," I respond and turn around, walking away slowly, my entire body tense. Will he do anything to me once I turn my back?

"Mommy, what did you say to him?" Rebecca asks me in German.

"I asked him when the bus would come," I reply, continuing to walk slowly, feeling my back painfully exposed.

"And what did he say? "

"That the bus will not come today," I near the group of people standing in the yard and allow myself to turn around and relax. He is still there, watching me, his hands at his sides and his gun resting on his shoulder. After a moment, he turns and rejoins his friends sitting on a wooden bench outside the barrack, observing us.

"Mommy, is he a good hunter or a bad hunter?" Rebecca asks, and I feel her arms wrap around me.

"I don't know, sweetie," I keep my eyes on him, "I don't know."

It's night and dark outside as Charlotte and I lie in our room. Rebecca is already asleep, and the people in the surrounding apartments have finally fallen silent.

The searchlight from the watchtower occasionally passes over the walls of the building, its strong beam illuminating the room for a moment before being replaced by the blackout darkness. I can hear a woman and a man faintly talking outside at one of the entrances, but they also fall silent, and peace reigns in the camp again.

"There will always be women willing to sell," Charlotte says quietly.

"Themselves?" I whisper to her. "Who will buy? Everyone's money is running out."

"There are always those who have money," I hear her from the darkness. "They say the French police also come to visit at night," she says ironically. "In the morning, they point a weapon at you, and at night, they point another weapon at you."

"They delight in taking the hardest payment from us."

"Especially when we're alone; we're easy prey."

"It's hard to be alone again, especially after I got used to trusting him," I say to her, debating whether to tell her about the offer I received from the smuggler just because I was alone with a girl and my husband wasn't there. I'm sure she faced such suggestions during the years she was without a man to protect her. "What about Mr. Salomon?" I ask after a while, even though it may not be appropriate. "Wasn't there someone?"

"Men don't want to marry women like me," she whispers.

"What does that mean?"

"Scatterbrains, women who want to be independent, to create," she says. "Those who love their freedom."

"There must also be men who love their freedom, don't you think?" I try to understand what she means. I like having a man who watches over me, even if he isn't here now.

"The Nazis came to power in 1933. They've been persecuting me for eight years," she pauses for a moment before continuing. "I wanted to be free from them, so I fled to the south of France, to Nice. The men I knew in Berlin at that time didn't think freedom was so important and stayed. But it didn't change anything. The Nazis had other plans, and they also came to France and caught me."

"And you came here alone? Didn't you meet anyone there?"

"Do you see anyone else in this room with me besides you and your girl? "

"Sorry, I didn't mean to offend you," I say quietly.

"I left my family in Berlin. I had grandparents in Nice, and I stayed with them," she says after a while.

"And what happened to your family?"

"They had different notions about freedom, like committing suicide instead of living under the Nazis regime, except for one of them who tried to touch me. Apparently, the desire for women to pay with sex doesn't go away with age. Nor does it disappear within the family. As you can imagine, after that, I wasn't into men."

"I'm sorry that happened to you," I say, wanting to hug her, but unsure how she'll react or if it's appropriate.

"It's okay. I've always had my world that allows me to escape into my freedom."

"What worlds?" I ask as I caress Rebecca's head, who is sleeping next to me.

"You're also alone now, without a husband," she changes the subject.

"Yes, I'm on my own, and with a girl I have to care of."

"There is a classroom here for all the children. She should go there. The people here took one of the apartments and turned it into a school, so the children don't wander around all day doing nothing and fighting with each other like the adults."

"She doesn't know how to get along with other children. She has already met them in the yard, and they started fighting. She barely speaks French, and they make fun of her."

"They say there's a strict teacher there, Mr. Gaston. He'll take care of her. "

"I'm worried about her. How will she manage with the other children?"

"She has to learn to get along."

"Did you have a strict teacher at school? I don't think you knew how to get along with him," I whisper.

"No, I didn't know," she answers me, and I think she's laughing, "but I could run away to Nice in the south of France. She has nowhere to run, so she'll learn."

"Tomorrow, I will try to send her to the classroom," I continue stroking Rebecca's hair.

"You have to, so that she grows up like you and not like me."

"I just want us to get through this war and get out of here."

"Then send her tomorrow so she can learn French, at least."

"Good night, Charlotte," I say to her after a while.

"Good night, Sarah," she answers, and I close my eyes. It's good to have someone here to talk to at night, not just a five-and-a-half-year-old girl.

"Do I have to go to school?" Rebecca asks me the following morning.

"Yes, you must," I give her two slices of bread I saved for her from yesterday.

"And what if the bus arrives?"

"It will come after you finish studying and playing with the other children," I bend down and tie her shoelaces. "The rabbit runs and jumps into the burrow, and there are his ears," I tell her as my fingers tie the loops, and she laughs. She needs to learn to tie her shoes. She also needs to laugh more.

"Do you think the hunters will hunt the rabbit?"

"No, the rabbit will run away quickly, they won't catch it. Now we're going to class. "

"What if the other kids hit me?"

"You need to learn to manage alone," I hold her hand as we leave the room.

"Bye, Ms. Charlotte," she says.

"Bye, Rebecca, behave yourself," Charlotte says, and we go down the stairwell between the neighbors' apartments and down to the yard.

A line of people is already waiting by the single faucet to fill buckets with water. I notice two policemen walking in the yard, patrolling the area. In the last few weeks, the fights and conflicts have increased as the camp becomes more crowded. Luckily, no one else has come to our room yet.

"Mommy, my stomach hurts," Rebecca whispers as we approach the class. On the concrete wall is a small sign that reads ‘School.'

"You'll have fun and meet new kids," I promise her, even though I don't believe my own promise. She needs the company of other children.

Slowly and quietly, I open the classroom door, and we both go inside.

The small room is full of children of different ages sitting on wooden chairs beside simple tables. At the front, the teacher stands next to a wooden board, writing words in French with chalk. Everyone turns their gaze toward us as we stand in the doorway.

"Yes, please?" The teacher stops writing on the board and asks me in a sharp voice. He has a large, narrow nose and is nearly bald, his baldness glistening in the sunlight coming through the window .

"I brought my daughter, Rebecca, to study," I say to him and smile awkwardly.

"Sit there," he points with a large wooden ruler he holds, indicating an empty chair at the end of the room. I lead Rebecca to the corner of the room and sit her in the empty chair. The girl sitting next to Rebecca is much older.

"Mommy, I don't feel well," she whispers in German as she tries to hold my hand tightly and refuses to let go. I hear the children around laughing.

"Quiet," the teacher thunders in his voice and hits the wooden ruler on his table, and everyone falls silent.

"Bye, Rebecca," I let go of her hand and stand next to her for another moment, looking around at the students. Most children are older than her, and they all look at us, scrutinizing Rebecca and me.

"Madame, may we continue our lesson?" The teacher turns to me with a scolding tone, and for a moment, I feel like a six-year-old girl who wants to run away from the classroom in the face of his angry look and the wooden ruler in his hand.

"Sorry," I say and rush out of the classroom in front of all the children's eyes and close the door behind me.

"Girl, get up and say your name," I hear the teacher say behind the closed door, and after a moment, the children laugh. What are they laughing at?

"Quiet," I hear him thunder again, and then the strike of the ruler. Although I want to go back in and take her with me, I turn my back and leave the building. She must learn to get along with the other children.

Later, shortly before the children finish school, I stand at the window and look out. I wait here for her, watching to see how she manages on her own. Many people walk around the large yard between the fences, enjoying the rays of the winter sun. They escape from the crowded rooms where there is only boredom, laundry hanging on ropes, and the smell of sweat. Anything is better than being idle and quarreling with each other.

The guards near the gate also come out of their guard post and stroll along the fence. In the distance, on the road that emerges between the houses and leads to the camp, I notice a German commander's army vehicle. I'm startled, even though there is no reason to be. They've already imprisoned us here. What else can they do to us?

"What did you say?" Charlotte asks and approaches the window beside me.

"I muttered something about being locked up here," I continue looking at the vehicle painted in gray-green camouflage colors as it slowly drives and stops in front of the German commander's barrack. A soldier gets out of the car and opens the back door. A woman in a gray coat and two girls in yellow dresses and brown coats emerge. The woman bends down and speaks to the girls, who nod their heads and start running in the grass in front of the hut while she stays to watch them. From a distance, they look a little older than Rebecca.

Suddenly, the door opens, and the Nazi officer emerges in his black uniform. He politely kisses his wife on the cheek and walks toward the girls, leaning down and spreading his arms toward them. They run to him for a hug. How can such an evil man be such a good father and hug his daughters like that? I look down and search for Rebecca in the large yard, but she hasn't left the study room yet .

"Captain Carl Backer. His wife and daughters come to visit him now and then and play out here," Charlotte says bitterly. "Like every good German family, they come to visit dad at work."

"We Jews are their job," I say and look at them again. I think he takes a candy out of his pocket, and they clap their hands excitedly. "Sometimes I think they just want to wipe us from the earth."

"Then they won't have any more work to do," Charlotte chuckles. "Sarah, the children are out of school," she points with her head at the yard, and I stop looking at the commander's daughters who are playing outside the fence and search for Rebecca inside our prison.

She is playing tag with the other children. They chase each other in the yard among all the adults, and I smile. Maybe she will manage after all. I can try to imagine that everything here is almost normal. Without the wire fences surrounding us and without the Nazis who hate us. Without the French police who guard the gates, the watchtowers, and without the constant nagging hunger in my stomach. I look again at the commander's daughters. One day, Rebecca will also be free like them.

Shouting voices from below make me move my eyes and look for Rebecca. To my horror, I see her pull another girl's hair while the girl screams in pain and tries to hit her. Why did she get involved again? I have to go down to separate them.

"Let her fend for herself," Charlotte says to me.

"But that girl is hitting her."

"If she doesn't learn to fight back, they will always beat her," she says quietly, and I remain standing, watching as several other children surround them and beat Rebecca, who struggles with them like a wounded animal.

"I have to go down and help her," I feel the tears well up in my eyes.

"She's doing fine. Look, that's how kids are," Charlotte points with her head. Rebecca manages to free herself from them and runs away toward the fence surrounding the complex. The children chase her at first, but as they get close to the fence, they leave her and return to their game of tag as she watches them from a safe distance. I hope she didn't rip her dress. I've already had to sew it twice.

I look at her. She's so alone there, standing by the barbed wire fence. But Charlotte is right. I can't protect her. I must let her learn how to manage on her own. She turns and looks at the camp commander's daughters, who are playing outside the Germans' barracks, and then she starts walking and approaches the gate. What is she doing? Does she want to join them?

"Rebecca," I shout to her even though she is far away and can't hear me, "Rebecca," I scream again, step away from the window, leave our room, and run down the stairs to the yard. Why is she going to the gate? She knows it's not allowed. Why didn't I go downstairs when she started fighting with the kids? Run, run, don't stop. I pass two women and a man slowly climbing up the stairs, pushing myself between them without apologizing and keep running. What will the police do to her if she approaches them?

From the building's exit, I continue to run toward the gate. I see her standing with her back to me and talking to one of the gate policemen at the gate. I approach and pick her up .

"Sorry, officer, she's just a little girl," I tell him as I hold her tightly while panting, "Rebecca, you mustn't talk to the policeman like that," I say and take a few steps back from him, so he won't punish us.

"Then why did she ask me?" He asks me, and I turn my eyes away from Rebecca and see that it is Mathéo, the policeman with the round glasses.

"Sorry, I apologize," I say, still panting. "What did she ask you? Rebecca, did you want to go outside?" I look at her again.

"She asked me if I was a good hunter."

"She's sorry," I say. "She's just a little girl. She confuses reality with stories she hears," I look into his eyes. Does he have kind eyes? He doesn't smile at me, and the other policeman at the gate, who is not far away, listens to us. "Rebecca, apologize to the policeman," I tell her firmly . Why did she do that?

"I didn't mean to," she begins to cry.

"Tell her I can't protect her from the other kids." The policeman says.

"Sorry, it won't happen again, I promise," I start slowly walking back, away from him, while holding her tightly. I want to scream at him, and tell him to speak to her directly. I also want to yell at her father that I need his help.

"You can go now," he tells me quietly and nods. Still panting, I turn my back to him and start walking to the building. I'll have to figure out how to discipline her.

"You're not allowed to talk to the police," I raise my voice at her when we reach our room. "Now turn around and face the wall." I lose control of myself and spank her, ignoring her cries. "You need to behave," I hit her again while she whimpers in pain. Around me, I notice some neighbors from the surrounding apartments have come to see what the noise is about, but I ignore them. I feel a surge of anger until I want to scream. "You need to learn to get along with the other kids," I continue yelling at her.

"Great, it's time to teach the little German a lesson," I think I hear one of the neighbors say, but I don't respond.

"She causes trouble for everyone. It's good her mother realized it was time to discipline her," says another neighbor.

"Enough, enough, she's learned her lesson," Charlotte puts her hand on my arm.

"She needs to learn," I respond to Charlotte and turn back to Rebecca. "I'd rather you cry now than later," I shout at her while she screams. "Now go to the corner and calm down." I release her and walk past the onlookers who have entered the apartment to witness the scene. I head to the stairwell. It's so difficult to care for her all the time in this wretched place.

Only in the stairwell do I sit down and let my tears flow, not bothering to wipe them away. Why isn't he here to discipline her? It's the father's job.

Later that night, when it's already dark, and Rebecca has fallen asleep, I stroke her hair. I couldn't bring myself to hit her with a belt or a shoe as others did.

"She'll be fine," Charlotte whispers to me.

"Yes," I reply, trying to wipe away the tears that pour down my cheeks every time I think about what I did to her. Life here is so hard.

"She has to grow up. There's no other option."

"She's a five-and-a-half-year-old girl, not yet six. She doesn't even know how to tie her shoes yet. How grown up does she have to be? "

"I don't know anymore," Charlotte says. "What will happen if you won't be here to protect her?"

Fullepub

Fullepub