Sam

SAM

Samuel Smith is not a happy man.

As a young boy, he was obsessed with horror and crime novels. He devoured books by Stephen King and Agatha Christie, and dreamed of being a detective one day. Becoming a private investigator was as close as he got. When Sam celebrated his fortieth birthday alone, drinking warm beer and eating cold pizza in his London flat, he made a confession to himself: this was not living the dream.

But the next day—when Sam was feeling rather worse for wear—an elderly man called. He asked for Sam’s professional help to keep an eye on his estranged daughter. The old man was reluctant to tell him his name at first, but being a PI was a job that required facts, so Sam had to insist. Eventually, the caller confessed he was Henry Winter, and Sam’s disappointing career suddenly became a lot more interesting.

He thought it must be joke, a belated birthday windup by a friend perhaps, but then remembered that he didn’t have any. Reading books was how Sam spent most evenings. His favorites were the creepiest ones, and Henry Winter was the king of horror in Sam’s eyes. He had been reading the author’s stories since he was a teenager. Once he had checked a few facts, and made sure it was the real Henry Winter who was asking for his help, Sam would have been happy to do the work for free.

But a man has got to eat.

It wasn’t as though the elderly author was short of a bob or two: quite the opposite. But Sam still started to feel bad about how much he was charging him. Following Henry’s daughter and keeping tabs on her husband was easy money.

Sam likes to think that he and Henry became friends over the years that followed, and in some ways they did. Sam even managed to persuade the old man to get a laptop, so that they could email from time to time. He would follow Robin or her husband twice a week or so—when they walked the dog, or on their way to work, or sometimes he just sat outside their house in Hampstead Village—just to keep track of things. Then he sent a monthly report Henry’s way. But their exchanges weren’t all work related. They often chatted about books, or politics, instead of Robin and Adam. Sam took great pride in the fact that Henry trusted and confided in him, even though they had never met.

They spoke at least once a month, so when he didn’t hear from Henry for a while, Sam started to get a little concerned. First, the phone calls stopped and were never answered or returned, but back then Henry still replied to emails occasionally. He was surprisingly keen to see pictures of the dog all of a sudden, and wanted to know every detail when his daughter’s home was redecorated after she moved out. Sam’s long lens camera came in very handy on those occasions. But the author never used the same friendly tone he had before, and then all communication came to an abrupt end, along with his regular payments.

Sam had been keeping an eye on Henry’s daughter for more than ten years, and it made him sad when his relationship with the author ended suddenly and with no explanation. He drank more beer, ate more pizza, and didn’t buy the latest Henry Winter novel until the day after it came out, in protest. Sam had been a silent part of the family since Robin married Adam. He was there when her husband started having an affair, and he felt a bit down himself when they got divorced. Digging around in the dirt of their marriage was easy work, but that wasn’t the only reason why he did it for as long as he had. They were an interesting couple to keep tabs on: him with his writing, and her with a famous father, and a secret past. Sam had even grown rather attached to their dog, having watched Bob since he was a puppy. So he was genuinely sad when things went wrong for Mr. and Mrs. Wright.

When the daughter moved back in with her ex-husband a few months ago, after disappearing from the face of the planet for a couple of years, Sam decided to drive to Scotland and tell Henry about it in person. The author had always been painstakingly private and had refused to ever share his home address, but of course Sam knew where he lived. He might not have made it as a detective, but he still knew how to find out most things about most people.

Newspaper interviews with Henry Winter were rare, but Sam had kept one from a few years back. It was about where the author liked to write, and showed a picture of Henry in his study, sitting at an antique desk that once belonged to Agatha Christie. It didn’t take long for Sam to find out which auction house the desk had come from. Or to bribe a delivery driver to give him the address where it had been sent.

Henry’s Scottish hideaway was still harder to find than Sam could have imagined. The drive up from London was painfully long and slow, and without directions the postcode he’d been given proved close to useless. After driving around in circles looking for the mysterious—possibly nonexistent—Blackwater Chapel, and passing endless mountains and lochs that had all started to look the same, Sam went back on himself to Hollowgrove, the only town he had seen for miles.

There was only one shop, it was getting dark, and Sam spotted the woman putting up a CLOSED sign in the window as soon as she saw him climbing out of his car. He knocked anyway, and she pulled a face that was even more unpleasant than the one she had been wearing before.

The woman opened the door and Sam noticed her name badge: PATTY.

She had a face like a carp and it was as red as her apron. Her beady eyes glared and she barked the word “what” at him with venomlike spit. She was clearly a woman who was good at making people feel bad. Sam resisted the urge to offer his condolences for Patty’s sister, who he was sure had been murdered by a girl called Dorothy near a yellow brick road. But Patty’s distinct lack of kindness turned out to be very helpful.

“Nobody has seen Henry Winter for a couple of years, and good riddance I say. He fired his old housekeeper with no notice—she was a friend of mine. The new housekeeper used to pop in now and then to get supplies—odd woman with a sweet tooth for baked beans and baby food—but even she stopped coming to town a few months ago. I don’t know if I should tell you how to get to Blackwater Chapel. I don’t want you coming back here and blaming me if something bad happens. That place isn’t just haunted, it’s cursed. Ask anyone.”

Sam bought a bottle of overpriced whiskey—he didn’t want to meet his friend empty-handed—and the old crow gave him directions anyway. When Sam gave her a ten-pound note to say thank you, she drew him a map.

Sam felt like a character in one of his favorite detective novels once he was back on the road. The phone calls from Henry ended around two years earlier—the same time the woman in the shop said the author stopped going into town. Sam didn’t know anything about a housekeeper, old or new, Henry never mentioned them. The only person Henry ever really wanted to talk about was his daughter, Robin. Their estrangement still bothered Sam, because it clearly made the old author very sad indeed.

Robin was a difficult child. Her mother—a romance novelist who Henry met at a literary festival back in the day—died when the girl was only eight years old. She drowned in the bath. Robin had two authors for parents, so it probably shouldn’t have been a surprise that she struggled to separate fact from fiction. Henry said she was always making up stories, and it got her in trouble at boarding school as well as at home. She got suspended once, for telling girls in her dormitory tales about witches who whispered their victim’s names three times before killing them. It was all just the result of an overactive imagination—which to be fair, she’d inherited—but when Henry tried to discipline her, Robin cut off her own hair with a pair of scissors one night, leaving two long blond plaits for him to find on her pillow.

Henry blamed grief, and himself, but nothing he did to try to help the child worked. She ran away from Blackwater Chapel too many times for him to count, and when she was eighteen, she ran away for good. Henry didn’t know where she was for years, until Robin got in touch asking him to help her husband. Henry was fond of Adam from the start. He always sounded like he was smiling when he talked about the man Robin married. He didn’t like the screen adaptations of his novels, but the fact he continued to agree to them was testament to how much he liked Adam. It was obvious that he grew to think of his secret son-in-law as the son he never had. He thought Adam had been a good influence on his daughter’s life, and so long as she was happy, he was happy to stay out of it. That’s all he wanted to know when he asked Sam to follow them.

Was she happy?

Robin was always fond of writing letters as a child, as well as making things up that got her into trouble. She wrote Henry one last letter before she ran away to London. It was a thank-you, as well as a goodbye. She said the only thing that he had ever given her that she truly loved was her name. Her mother had insisted they christen her Alexandra, but Henry never liked that, so always used the child’s middle name instead, the one he had chosen: Robin. He said she liked it so much because it made her feel like a bird, and birds can always fly away. When Robin flew, she never came back.

Sam kept one eye on the winding Highland roads—which were difficult enough to navigate even before it got dark. He also kept glancing down at the hand-drawn map the woman in the shop had given him, trying to make sense of it. He noticed that Patty had also scribbled down her phone number. Sam shuddered. Despite being lost in the desert for a long time when it came to the ladies, he’d rather die of thirst than drink at that well. When he turned off the main road, he saw that there had been a sign for Blackwater Loch all along. He’d driven past it several times earlier because, by the looks of it, the sign had been chopped down. Possibly with an axe. This was clearly a place someone didn’t want people to find.

He drove along a little track, narrowly avoided hitting some sheep, and passed a small thatched cottage on the right. It looked abandoned. Sam was about to give up, had decided to maybe try and find a hotel for the night, but then his headlights illuminated the shape of an old white chapel in the distance.

Sam’s fuel gauge was low but his hopes were high as he parked his thirdhand BMW outside. His optimism didn’t last long. The chapel was in total darkness. He could already tell that nobody was home: the big old wooden doors weren’t just closed; they were chained together with a padlock. Henry clearly wasn’t there, and from the thick cobwebs covering the doors, it appeared he hadn’t been for some time.

Upset at the thought of a wasted journey, and not quite ready to give up, Sam grabbed his torch from the boot of the car and went for a walk around the chapel. He hoped he might find another way in, but despite endless stained-glass windows there were no other doors. He did stumble across several wooden statues in the dark though. The eerie-looking rabbits and owls carved from ancient tree stumps, were so well hidden by shadows, that Sam walked right into the first one and automatically apologized before taking a step back. Their ghoulish, gouged eyes made him shiver. But then he felt a strange surge of relief—Henry had talked to him about how much he loved to carve wood, he found it calming after a long day plotting to kill people—and Sam knew that he was at least in the right place.

Then he found the cemetery at the back of the chapel.

The granite headstones blended in with the rest of the pitch-black scenery at first, but when Sam got closer, his torchlight revealed that most were seriously old. So much so they were either leaning at angles, falling apart, or covered in moss. But not all of them were ancient or impossible to read. The newest one, which stood out from its crumbling neighbors in the distance, and couldn’t have been more than a year or two old, grabbed his attention. He headed in that direction, but tripped over an unexpected mound of dirt and dropped his torch. Sam was pretty hard to scare—he’d read all of Henry Winter’s novels twice—but even he had a dose of the heebie-jeebies as he crawled on his hands and knees, in a graveyard, late at night, trying to retrieve his torch. The heap of dirt suggested that someone had been recently buried there, and the grass hadn’t quite had enough time to grow over the uneven soil. There was no marker, no name, and it reminded him of a pauper’s grave. But then he noticed something sticking out of the ground … an old inhaler.

Sam felt uneasy all of a sudden, and the shopkeeper’s warning about the chapel being cursed returned to haunt his thoughts. Then he heard someone whisper his name three times in the shadows just behind him.

Samuel. Samuel. Samuel.

But when he spun around, there was nobody there.

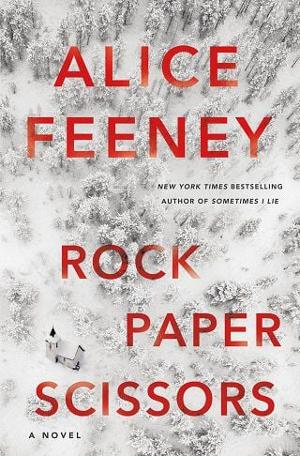

It must have just been the wind. Fear and imagination can lead the brightest of people down dark paths. No wonder a child growing up here imagined so many awful and twisted tales confusing fact and fiction, he thought, remembering all the stories that Henry said Robin had made up. He was going to ask the old man about that again as soon as he tracked him down. He had spotted a small police station in Hollowgrove, and made a mental note to stop there on the way back, hoping they might know where his friend was living now. Somebody must. World-famous authors don’t just disappear. Besides, Henry had a new book called Rock Paper Scissors coming out next year. Sam knew because he had already preordered it.

He picked himself and the torch up off the muddy ground, and walked over to the newest-looking headstone in the cemetery. He had to read what was engraved on it several times before his brain could begin to process the words.

HENRY WINTER

FATHERKILLER OF ONE, AUTHOR OF MANY.

He didn’t believe at first that Henry was dead.

There was a tiny glass box on the grave, the kind someone might keep trinkets inside. Sam shone his torch on it, and hesitated before bending down to take a closer look. When he did, he saw that the box contained three items. A sapphire ring, a paper crane, and a small pair of vintage scissors designed to look like a stork. It was the ring that caught his eye, not just because of the sparkling blue rock, but because it was still attached to what appeared to be a human finger. The wind picked up then, and Sam thought he heard someone whisper his name again, three times. He didn’t believe in ghosts, but he ran to his car as fast as he could and didn’t look back.

Fullepub

Fullepub