Robin

ROBIN

Robin remembers walking away from the house in London, the day she found Adam and Amelia in bed together. She remembers the magnolia tree, and she remembers taking off the sapphire engagement ring that had once belonged to Adam’s mother, along with her wedding ring, and leaving them behind on the kitchen table. The rest is a blur at best. She grabbed her bag, a few of her favorite things, then got in her car and just drove. She didn’t know what she was going to do, or where she was going to go, she just had to get far, far away from them, as fast as possible. Her biggest mistake was leaving Bob behind. The only people with no regrets are liars.

That was when Henry called. To tell her he was dying and to ask her to come home.

Robin hadn’t spoken to her father for years, but a series of fallen stars seemed to align themselves that afternoon, to guide her back to the home she ran away from as a child. Truth be told, she had nowhere else to go.

Robin still remembers when Amelia first started volunteering at Battersea Dogs Home, and how she took pity on the mousy, lonely creature, in the same way she took pity on all the abandoned animals that arrived there. She helped Amelia to get a job, and a life, became her friend, and in return the woman stole her husband. She looks so different now, with her blond hair, fancy clothes, and Robin’s ex-husband on her arm. But, as awful as being betrayed by a friend is, it was Adam who Robin blamed at first. For everything.

Not anymore.

Now she blames them both, which is what this weekend is really about and why she tricked them into coming here.

Robin has experienced grief only three times in her life:

When she stopped trying to have a child of her own.

When her husband cheated on her.

And when her mother drowned in a claw-foot bath.

The whole world thought it was an accident, but it wasn’t. Robin has always believed that Henry was responsible for her mother’s death. That was why he really sent Robin away to boarding school, and why she ran away as soon as she was old enough to leave for good. He removed almost every trace of her mother from the Scottish chapel she had lovingly converted into a home. The bathtubs were the first to go. Her mother loved to cook, so Henry emptied almost every kitchen cupboard and drawer until there were only two of everything left; two plates, two sets of cutlery, two cups. No saucepans, no pots or pans, were left behind. The smell of cooking reminded him of his dead wife, so the old housekeeper would make big batches of meals at home instead, then fill the chapel freezer with them so they both didn’t starve. Robin kept what she could of her mother’s possessions, including two pairs of stork-shaped gold and silver embroidery scissors—her mother loved to sew, as well as cook—and hid them beneath her bed. She never believed that her mother’s death was accidental. People who read and write crime novels and thrillers know there are an infinite number of ways to get away with murder. Robin suspects that it happens all the time.

It always felt as though her parents were performing a part in a play they would rather not have been cast in. Is disinterest a form of neglect? Robin thinks so. But things were much worse after her mother died. Her world became very small and very lonely very fast. Henry thought throwing money at the problem would fix it, just like he always did, and it was why she never wanted a penny from him as an adult. She would rather sleep in a freezing cold cottage, with an outside toilet, than spend another night under his roof. His money was blood money in more ways than one.

Henry bought the fanciest doll’s house Robin had ever seen when her mother died. Each room had the same two little figures inside it. One looked like Henry, the other was a miniature Robin. A happy toy family to replace their broken real one. He carved the dolls himself with his wood chisels, just like the statues outside the chapel, and all the Robin-shaped birds he had whittled over the years, while puffing on his pipe, or sipping a glass of scotch.

Nobody else knew what really happened to Robin’s mother. Nobody suspected a thing. Henry even wrote about a man who killed his wife in the bathtub a few years later in his novel called Drowning Your Sorrows. It made Robin question whether all of his stories might be based on facts rather than fiction, and the thought terrified her. The book was a huge bestseller, everyone at her boarding school was talking about it, even the teachers.

It inspired Robin to write a story of her own. Her English tutor was so impressed, that—unknown to Robin—she sent a copy to Henry at the end of term, saying that a gift for storytelling clearly ran in the family. It was about a novelist who committed crimes in real life, then wrote about them in his books, always getting away with murder.

When Robin came home that Christmas, Henry barely spoke to her at all. He stayed locked inside his secret study with his beloved books. Just like always. One afternoon she found her dolls floating in the bathroom sink. They looked like they were drowning, just like her mother had in the claw-foot bath. When she woke up on Christmas morning, there were no gifts in the stocking that hung at the end of her bed. The only thing that had changed in the night was that Robin’s hair had been cut. There were two long blond plaits lying on the pillow where she had slept, and her mother’s pretty stork scissors were on the bedside table.

Henry Winter didn’t just write about monsters. He was one.

He made her write lines as punishment for writing that story at school:

I must not tell tales

I must not tell tales.

I must not tell tales.

So Robin never wrote a word of fiction again.

Until Henry was dead.

After she buried him in the graveyard behind the chapel, Robin returned to the secret study that she had never been allowed to set foot inside as a child, and sat down at that antique desk. She took out her dead father’s laptop. Remembering the password was easy: it was her name. She found Henry’s uncompleted work in progress, and started reading. The idea sounded crazy inside her head at first. What other word was there to describe a woman who worked with dogs trying to finish a novel by an international best-selling author?

But that’s what she did.

Robin deleted most of what Henry had written—she didn’t think it was very good—and then replaced it with her own words. She wrote three drafts in three months, and when the book was finished, and she had edited it to the best of her ability, she felt as though the transition from her father’s story to hers felt seamless. Then she typed the whole book out again—on Henry’s typewriter, just the way he would have done. The real test would be sending it to his agent: if anyone could spot the difference, it would be him.

Robin already knew that Henry always wrapped his manuscripts in brown paper and tied them with string—she’d seen him do it often enough as a child—so she did the same, then drove the parcel to the post office.

Robin had barely left Blackwater since she arrived three months earlier. It seemed strange to her that the world outside the chapel’s big wooden doors was the same as the one she had lived in before, when Robin’s life had changed beyond recognition. There had been no reason to leave until then, and it was her first trip to Hollowgrove—the town closest to Blackwater Loch—for more than twenty years. But as Robin drove her old Land Rover, with the manuscript beside her on the passenger seat, she was still scared that someone might recognize her. They didn’t. But Patty in the corner shop, recognized the brown paper parcel instead.

“Is that a new book by Mr. Winter?” she asked, chewing bubble gum between words, like she was a teenager, not a woman in her late fifties. Robin felt her cheeks turn red and couldn’t answer. “It’s okay if it’s meant to be a secret, I can keep it,” Patty lied. “It’s just that’s how he always posts them—tied up in string and what not.”

Robin froze, still unable to speak. Patty’s eyes narrowed.

“Are you the new housekeeper? Heard he fired the last one…”

“Yes,” said Robin, without thinking it through.

Patty tapped the side of her nose with her index finger. “I see, pet. Probably told you not to tell anyone anything, didn’t he? As if anyone around here cares whether he’s written a new book. The only author I’ll ever love is Marian Keyes, now there’s a woman who knows how to write. Do I look like I have time to read the words of a madman? That’s what Henry Winter is if you ask me—all the disturbing books he’s written. You’ve my deepest sympathies working for an old miser like that. Don’t you worry about a thing, Patty will post and keep all your secrets.”

If only Patty had known how big Robin’s secrets really were.

After that, the waiting was the hardest part.

Robin finally understood how nerve-racking it is for writers to send their work out into the world. In the days after she posted the manuscript, she kept the curtains drawn, ate frozen meals when she was hungry, slept when she was too tired—or drunk—to stay awake, and completely lost track of what day it was. When the phone rang, she knew that she couldn’t answer it. Anyone calling would be expecting to hear Henry’s voice, including his agent, so she waited a while longer.

When a letter arrived from Henry’s agent the following day, it took Robin a few hours and another bottle of wine to feel brave enough to open it.

When she finally did, she cried.

Finished the novel in the early hours. It’s your best yet!

Will send to publishers today.

They were tears of joy, relief, and sorrow.

She wanted to tell someone, but Oscar the rabbit wasn’t the best at conversation. She’d renamed him the first day they met, because Oscar was a boy rabbit not a girl, unknown to Henry. And Robin was her name. It was the only good thing her father ever gave her. She was so proud of that novel, but the truth, whether spoken or not, was still impossible to ignore. Henry’s best book yet was really hers, but it would still be his name on the cover.

Robin tried to put the letter from Henry’s agent into one of the desk drawers—she didn’t want to look at it anymore—but the drawers were all too full. She pulled out the first few pages of what looked like an old manuscript, and was surprised to find her ex-husband’s name printed on the front:

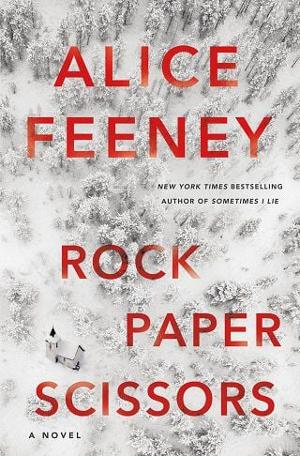

ROCK PAPER SCISSORS

By Adam Wright

Attached to it was a letter from Adam, dated several years ago:

I know how very busy you are, but I always wondered whether this screenplay might work as a novel? I think that might be my best chance of getting it made. I’d be very grateful for your opinion. I do hope you enjoyed the latest adaptation, your agent said that you did, and said he would pass on this letter for me. It was an honor to help bring your characters to life on screen. Any advice you can give me about my own would be gratefully received. It’s always been my dream and I like to think some dreams do come true.

It made her so sad that Adam had trusted her father with his most beloved work. She knew that Henry probably hadn’t even bothered to read it.

One of the few things that Robin took before she fled her home in London, was the box of anniversary letters she had secretly been writing to Adam every year. She still missed him—and Bob—every single day. She reread those letters that night, along with Adam’s screenplay, and a new idea formed in her head. The idea seemed too crazy at first, but she realized that there was a way to rewrite her own life story, and give herself a happier ending than life had so far chosen to.

Fullepub

Fullepub