Bronze

BRONZE

Word of the year:

atelophobianoun. The fear of not doing something right or the fear of not being good enough. An extreme anxiety of failure to achieve perfection.

29th February 2016—our eighth anniversary

Dear Adam,

We didn’t celebrate our anniversary this year.

I’ve been spending a lot of time with a friend from work and you’ve been, well, spending time with your work. You struggled with the latest adaptation of Henry Winter’s books. Personally, I think because you were trying too hard to please the author instead of being true to yourself. But as you said when I offered to try and help a couple of weeks ago, what do I know?

I do know that the lies we tell ourselves are always the most dangerous. And I know that sometimes the thoughts we hide in the margins of our minds are the most honest, because they are ours alone, and we think nobody else will see them. While you’ve been thinking about Henry Winter and his books, I have been thinking about leaving you.

My friend at work is kind, and caring, and genuinely interested in me. They never make me feel stupid, or insignificant, or taken for granted. Face blindness isn’t the only way that you make me feel invisible. You make me feel as though I’m not good enough every single day. It’s a terrible thing to confess, but sometimes I wonder if the only reason I stay is for Bob. And this house.

I love this big old beautiful Victorian relic, hidden away in a corner of London that time forgot. My blood, sweat, and tears literally went into every inch of the place while I restored it. With little and mostly no help from you. When we were younger, I didn’t dare to imagine we might share a home like this one day. You probably did; your dreams have always been bigger than mine. But then so are your nightmares. You and I had the kind of childhoods that are better forgotten, but seeds of ambition grow best in shallow soil.

How dare you invite him here without even asking me first.

I’d had such a difficult day at work—and, no offense, but my job is a real one, I don’t just sit around making shit up writing all day—all I wanted was to come home, shower, and open a bottle of wine. I could hear voices inside the house before I had even put my key in the door. Yours and one other. And it smelled like something was burning. I found you in the lounge, drinking whiskey with Henry Winter, while he smoked a pipe in our non-smoking home. I thought I was imagining it at first, but the tweed jacket and silk bow tie looked authentic enough to be real.

“Hello, darling. We have a visitor,” you said, as if I couldn’t see that for myself.

Anyone else would have recognized the look of horror on my face, he did, but you didn’t because you can’t. Still, I would have thought you could have picked up on my extreme discomfort in another way. Sometimes you display the emotional intelligence of a brain-damaged frog.

Both of you stared at me, waiting for me to speak, but what could I say? One of you was completely clueless about the situation, while the other seemed only too happy about it.

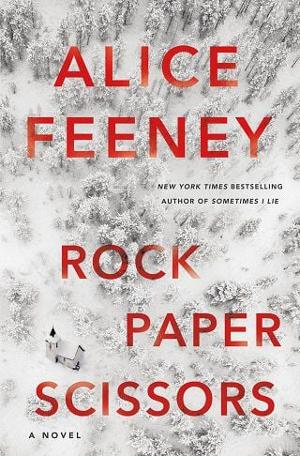

“Look, this is Henry’s new book,” you said, holding up a bright red hardback and looking pleased as punch, as though you had written it yourself and wanted a gold star.

Henry gave a shrug of false modesty. “It’s probably not your cup of tea.”

“Not really, no. I see enough horror in the real world,” I replied. You might not be able to read the expressions on my face, but I’m fluent in yours, and if looks could kill I would have been in the morgue. We could have cut the tension with a teaspoon, so it wasn’t surprising that Henry picked up on it.

“I’m so sorry to intrude. I sold my London flat last year and retreated to my Scottish hideaway full-time—you and Adam must come to visit—I’ve got a meeting with my publisher in town tomorrow, but there was some last-minute problem with my hotel reservation, and your husband insisted I stay here”—I didn’t say a word—“but I don’t want to intrude. I could always—”

“You’re more than welcome here. Isn’t he, darling?” you interrupted, looking at me.

“Of course,” I said. “I’m actually just getting changed and popping out to see a friend. I hope you have a lovely evening.”

I felt like an unwanted guest in my own home.

I practically ran up the stairs and packed a bag. I spent the entire weekend with my friend from work. We went to an art gallery one day, and the theater the next. I felt alive, and happy, and free. I enjoy her company more than yours these days. She tends to like animals more than people too, that’s why she started volunteering at Battersea Dogs Home. She listens to me, laughs at my jokes, and doesn’t make me feel second-best all the time. She’s a bit too fond of microwave meals and tinned food for lunch—I’ve never seen her eat a salad or anything green—but nobody is perfect and there are plenty of worse things in life to be addicted to.

When I came home at the end of the weekend, I was relieved that Henry was gone. It made me sad that you didn’t seem to really care where I had been or who I was with. You knew it was a friend from work, but you didn’t even ask what their name was. Instead, you just stared at me with a peculiar look on your face.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, fussing over Bob who clearly missed me more than you did.

“Nothing is wrong,” you said in that sulky man-boy tone that meant something was. “You’ve changed your hair.”

“Just a trim.”

You recognize my hair more than you recognize my face, and it always seems to bother you a little when I change it. It’s honestly only an inch shorter, and with a few more highlights than before, but it’s nice to feel noticed. I felt like pampering myself a little, as though I deserved a treat, but I could tell from your face that something else was on your mind.

“Do you want to tell me what’s bothering you now or after dinner?” I asked.

“Nothing is bothering me.” You pouted like a spoiled child. “I finished my screenplay today … and I wondered if you might like a drink at the pub to celebrate?” I was about to politely protest that I was tired, but you preempted my refusal with more words of your own. “Also, I wondered if you might read it, before I send it to my agent?”

And there it was, not just in your voice, but in your eyes.

You still needed me.

Despite all the writer-shaped colleagues and friends in your life, in London and LA, you still cared what I thought of your work. Just like when we first met.

“I didn’t think I was still your first reader?” I said, my turn to sound petulant.

“Of course. Your opinion has always mattered most. Who do you think I’m secretly writing all these stories for?”

I tried very hard not to cry. “Me?”

“Almost always.”

That made me smile. “I’ll think about it.”

“Maybe a game of rock paper scissors would help make the decision?”

“Maybe we should play for something else?” I said, forcing myself to look you in the eye.

“Like what?”

“Like … whether or not we should still be together?”

That got your attention—even more than the hair—and neither of us was smiling then. I don’t know what I expected you to say, but it wasn’t …

“Okay. Let’s do it. A game of rock paper scissors shall decide the future of our marriage. If I lose, it’s over.”

I was no longer sure who was calling whose bluff or if that was what it was. You have always let me win whenever we played the game. My scissors would cut your paper. Every. Single. Time. I don’t know what made me want things to be different, but my hand formed a new shape. To my surprise, yours did too.

On the first go, we both formed a rock, and it was a tie.

But if I hadn’t changed my choice … you would have won.

On the second go, we both chose paper.

With the stakes considerably higher than normal, the third round of this child’s game felt ridiculously tense.

We played again. I chose to twist, but you decided to stick. Your paper-shaped fingers wrapped around my rock-shaped fist, and you won.

“I guess that means we stay together,” I said.

You held on to both of my hands then, and pulled me closer.

“It means sometimes life changes people, even us. We are both different versions of ourselves compared with who we were when we first met. Almost unrecognizable in some ways. But I love all the versions of you. And no matter how much we change, how I feel about you never will,” you said, and I wanted to believe you. We’ve come so far, you and I, and we did it together. That’s why I can’t let us fall apart.

We didn’t go to the pub, and we didn’t do very much to celebrate our anniversary this year, I stayed up late to read your work instead. It was good. Maybe your best. Feeling needed isn’t the same as feeling loved, but it’s close enough to remind me of who we used to be. I want to find that version of us again, and warn them not to let life change who they are too much.

I left my notes about the manuscript, along with my anniversary gift to you on the kitchen table, before leaving for work early the next day. It was a small bronze statue of a rabbit leaping into the air. You thought it was something to do with Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—knowing that was one of my favorite books as a child—but you were wrong. I bought it because it reminded me of a Russian proverb that an old man once taught me. I’m still rather fond of it:

If you chase two rabbits, you will not catch either one.

You gave me a bronze compass a few days later, with the following inscription:

SO YOU CAN ALWAYS FIND YOUR WAY BACK TO ME.

I hadn’t realized that you thought I was lost.

Your wife

xx

Fullepub

Fullepub