Adam

ADAM

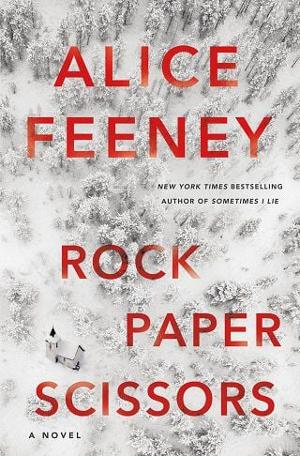

We run out into the snow.

I don’t know what to expect. Henry Winter standing outside the chapel? Holding Bob’s lead, and laughing manically like a comedy villain? Maybe he has finally lost his remaining marbles? The man writes dark and twisted fiction, but I still struggle to believe he would be capable of something like this in real life.

The sound of a dog barking stops as soon as we step outside.

“Bob!” Amelia calls.

It’s pointless—the poor old thing is practically deaf at the best of times—but I start shouting his name too.

The valley is now eerily silent.

“Maybe it wasn’t Bob?” I say.

“It was him, I know it,” she insists. “There were a pair of men’s Wellington boots by the door when I got back, now they’re gone. Whoever was here before left and they’ve got Bob with them.”

She runs farther out into the snow and I have no choice but to follow her.

The sheep are back. They stare in our direction, but aren’t as scary as they were in the dark last night. We both stop in our tracks when we see the back of a person wearing a tweed jacket, dark trousers, and what looks like a panama hat … in the middle of winter … in freezing cold snow up to their knees. Amelia looks in my direction. I can’t read the expression on her face, but if it’s anything like what I’m feeling, I expect it is one of terror.

I remind myself that I used to know this man—as well as you can know someone you work with and have only met a handful of times. I clear my throat and take a step closer.

“Henry?” I say gently.

For some reason, I remember the antlers on the wall of the boot room. It occurs to me that authors of murder mysteries and thrillers probably know a lot of ways to kill a person without getting caught, and I don’t especially want to have my remains mounted on a wall. He doesn’t move. I tell myself he’s probably just a bit deaf, like the dog, and carry on until we are face-to-face.

Except he doesn’t have a face.

What I appear to be looking at is some kind of scarecrow, but with the head of a snowman. He has wine corks for eyes, a carrot for a nose, a pipe sticking out of the space where his mouth should be, and one of Henry Winter’s silk blue bow ties tied around his neck. It’s a shade darker than it should be, saturated with melting snow. Henry’s walking stick, the one with the silver rabbit’s head handle is leaning against it, as though for support.

Amelia comes to stand by my side. “What the—”

“I don’t know anymore.”

“This wasn’t here before, was it?”

“No. I think we would have noticed. I really don’t understand what is happening.”

We stand side by side in silence, staring at the scarecrow snowman as his head slowly melts. One of his cork eyes has already slipped halfway down his face. Apart from the odd dead-looking tree and creepy-looking wooden sculptures, we are in the middle of a vast open area. Whoever did this must be close by. And if Bob is near enough to be heard barking, we should be able to spot him, but all I can see is empty white space. Thanks to the sheep, the snow has been disturbed almost everywhere outside the chapel. If there were any footprints to follow, there aren’t now.

“We have to find Bob. He’s out here somewhere, we both heard him, and we just have to keep looking,” Amelia says, and I follow her.

There is a small cemetery at the back of the chapel. The old gravestones are barely visible thanks to the snow, but one stands out as I get nearer. The reason it catches my eye is because someone has wiped it clean, so that the dark gray granite stands out against everything else covered in white. And, unlike all the other headstones, this one looks relatively new.

That isn’t all.

There is a red leather collar sitting on top of it.

Amelia picks it up and I see Bob’s name on the tag, as though there had been any doubt in my mind that it belonged to him.

“I don’t understand. Why remove the dog’s collar and leave it here?” she says.

But I don’t reply. I’m too busy staring at the headstone.

HENRY WINTER

FATHER OF ONE, AUTHOR OF MANY.

1937–2018

Fullepub

Fullepub