Copper

COPPER

Word of the year:

discombobulatedadjective. Feeling confused and disconcerted.

28th February 2015—our seventh anniversary

Dear Adam,

It’s been a difficult year.

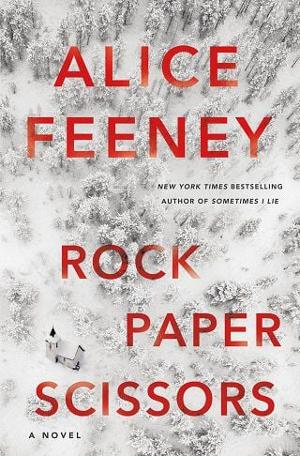

October O’Brien was found dead in a London hotel a few months ago, and you were one of the last people to see her alive. Suspected suicide according to the newspapers. There was no note, but empty bottles of alcohol and pills were found by her bed. It was obviously devastating. And surprising; the woman always seemed so happy and positive, at least on the outside. Barely thirty years old and everything to live for. The two of you had become quite close—I was rather fond of her myself—but it also means that the filming of Rock Paper Scissors has been canceled. You can’t make a TV series without the star of the show.

The funeral was awful. You could tell that so many people there were merely acting out what they thought grief should be. Two-faced shysters. It seems that genuine friends are even harder to come by when you’re famous. I was surprised to discover that October’s real name was Rainbow O’Brien. Her parents were hippies, and nobody at the service wore black.

“Thank goodness she used a stage name,” you whispered.

I nodded, but wasn’t sure whether I agreed. She was a bit like a rainbow: beautiful, captivating, colorful, and gone from our lives almost as soon as she appeared in them. I used to think a name was just a name. Now I’m not so sure. I had become quite friendly with October myself—occasional drinks, dog walks, and visits to art galleries—and I miss her too. It does feel like something, not just someone, is missing from both of our lives now that she is no longer in them.

A trip to New York sounded like a great way to spend our seventh anniversary and take our minds off it all, until I realized that it coincided with the premiere of Henry Winter’s latest film, The Black House. You were so eager to please flattered when he told his agent and the studio that he would only attend if you did. You thought it was because he was pleased with the adaptation, and wanted you to get the credit you deserved for writing the screenplay. But that wasn’t why he wanted you there. Or why he suggested you invite your wife.

You’ve been moody as hell a little distant recently, and I didn’t want to start another fight, but playing gooseberry to a pair of writers while they basked in the temporary warmth of Hollywood’s fickle sun didn’t appeal much. Neither did walking down the red carpet at the old movie theater in Manhattan where the premiere was held. The Ziegfeld was my kind of place—an old-school cinema decorated in red and gold, with a sea of plush red velvet seats. But being photographed on the way in made me feel like a fraud. I hate having my picture taken at the best of times, and compared with all the beautiful creatures in attendance—with their tiny waists and big hair—I worried that I must be a disappointment to you. It’s hard to shine when surrounded by stars. The idea of just being normal seems to make you so unhappy, but it’s all I ever wanted us to be.

The deal was that we would spend time alone together after the premiere, but then Henry wanted you to accompany him to a few more events the next day. I understand why you couldn’t say no; I just wish that you hadn’t wanted to say yes. I get that you’ve always been a huge fan of his, and I understand how grateful you are that he let you adapt his work. I know what it’s meant for your career, but haven’t I already paid the price for that? Wandering around a city on my own while you hold an author’s hand instead of mine, is not my idea of a happy anniversary.

You haven’t been yourself for a while. I know that you are grieving for October, I understand that she was more than just a colleague, and the dream of seeing your own work on screen stalling, again, must also be upsetting. But it still feels as if there is something else going on. Something you’re not telling me. There are residents in our lives, the ones who stay for years, and then there are the tourists just passing through. Sometimes it can be hard to tell the difference. We can’t, and don’t, and shouldn’t try to hold on to everyone that we meet, and I’ve met a lot of tourists in my life, people I should have kept at a safe distance. If you don’t let anyone get too close, they can’t hurt you.

I spent today alone, visiting the parts of New York I’d never seen before, while you followed Henry Winter around the city. The elderly author might seem charming to you, on the rare occasions when you have been in his company, but in real life the man lives like a hermit, drinks like a fish, and is impossible to please. I can’t tell you that, because I shouldn’t know. I’ve read all of his novels, too, just like you. His most recent was mediocre at best, but you still act as though the man is Shakespeare reincarnated.

I tried not to think about it when I visited the Statue of Liberty. The ferry to the island was jam-packed, but I still felt alone. Inside the monument, I joined a group of strangers for a tour. There were families, couples, friends, and as we climbed the staircase, I realized that everyone seemed to have someone to share the experience with. Except me. A friend from work texted to ask how the trip was going. I haven’t known them very long, and it seemed a little overfamiliar, so I didn’t reply.

There are three hundred and fifty-four steps to the Statue of Liberty’s crown. I silently counted the reasons why we were still together as I climbed them. There are still plenty of good things about our marriage, but a growing number of bad ones make me feel like we are starting to unravel. This distance between us, the empty spaces in our hearts and words; it scares me. A lot of married couples we know are muddling along, but most of those have the glue of a young family to keep them stuck together. We only have us. I did something I never do at the top … I took a selfie.

I headed to Coney Island after that. I guess it must be busier in summer, but I quite liked wandering around the closed arcades. I even found a last-minute gift for you—the copper theme this year posed a bit of a challenge. We’ve had so many highs and lows over the course of our relationship, but I suppose year seven is supposed to be difficult. I’ve heard about the seven-year itch and I’m sure you must have too. Whatever happens, I know I won’t be the first to scratch it.

When my feet ached from all the walking, I headed back to the aptly named Library Hotel. It’s a small but perfectly formed boutique hideaway, full of books and personality. Every room has a subject and ours was math. Horror might have been more appropriate; given the way this evening has turned out.

I’d booked us a table for dinner—I knew you would forget to remember—at a nearby steak house called Benjamin that the concierge recommended. The decor and atmosphere made me think of The Shining meets The Godfather—which again seems rather fitting in hindsight—but the service and steaks were perfection. As was the wine. We drank two bottles of red while I listened to you tell me about your day with Henry. You didn’t ask about mine, or notice the new dress I’d bought in Bloomingdale’s. Paying me a compliment is something you only do by accident these days.

I forgot to wave tonight when you walked in to the restaurant, but somehow you still knew it was me. Given that all faces look the same to you, and I was wearing something you had never seen, your confidence as you sat down at our table was out of character and surprising. I was equally baffled by how much attention you paid the waitress, wondering how you recognized the beauty of her twentysomething features if you couldn’t see her face.

I think I knew we were going to argue even before you said what you said. Sometimes fights are like storms, and you can see them coming.

“I’m sorry to do this, but Henry wants me to go with him to LA. Given all the buzz around this film, the studio wants to adapt another of his books, and he says he’ll only entertain the idea if I go along to meet them and agree to write the screenplay.”

“What about Rock Paper Scissors? You’re not going to give up on that, are you? It’s terrible about October, but there are other actresses. Working on Henry’s novels was only supposed to be a stepping-stone to—”

“I hardly think writing a blockbuster film script of a best-selling novel, written by one of the most successful authors of all time, is a stepping-stone.”

“But the whole point of this was to help you to make TV shows and films of your own—not his—to do what you really wanted.”

“This is what I want. I’m sorry if my career choices aren’t good enough for you.”

We both knew that wasn’t what I meant, and I could see you weren’t really sorry at all.

“What about what I want? It was your idea to spend a few days in New York together and so far I’ve barely seen you—”

“Because I couldn’t leave you behind. I never would have heard the end of it.”

For once, it feels like I’m the one who can’t recognize my spouse. “What?”

“You don’t seem to have any friends or even a life of your own these days.”

“I have friends,” I say, struggling to think of the names of any to help back up my claim.

It’s hard when everyone my age that I used to know seems to have children now. They all disappeared inside their shiny new happy families, and the invites dried up. It reminded me of school a little … being shunned by the cool kids because I didn’t own the latest must-have accessory. I changed schools more than once growing up. I was always the new girl and everyone else had already known each other for years. I didn’t fit—I never do—but teenage girls can be cruel. I tried to make friends, and I succeeded for a while, but I was always on the outer solar system of those childhood relationships. Like a smaller, quieter planet, distantly orbiting the brighter, more beautiful, and popular ones.

I still tried to stay in touch—attending the occasional birthday party, or obligatory bachelorette party or wedding for someone I hadn’t spoken to for years—but as we all grew up, and grew apart, I guess I grew more distant. My childhood relationships set the tone for the ones I formed as an adult. It was self-preservation more than anything else on my part. I’ll never forget the woman who pretended to breast-feed her children until they were four years old. Always making excuses to avoid seeing me—as if my infertility might be catching. I care more about liking myself than being liked by others these days, and I don’t waste my time on fake friends anymore.

You reached for my hand, but I pulled it away, so you reached for your wine instead.

“I’m sorry,” you said, but I knew that you weren’t, not really. “I didn’t mean that,” you added, but it was just another lie. You did. “Henry is a sensitive writer. He really cares about his work and who he will trust with it. He’s had a difficult year—”

“I’ve had several. What about me? You’re acting like he’s your best friend all of a sudden. You hardly know the man.”

“I know him very well; we talk all the time.”

It’s been a while since I felt so discombobulated. I almost choked on my steak. “What?”

“Henry and I talk quite regularly. On the phone.”

“Since when? You’ve never mentioned it.”

“I didn’t know I had to tell you about everyone I speak to, or get your permission.”

We stared at each other for a moment.

“Happy anniversary,” I said, putting a tiny paper parcel on the table.

You pulled a face that made me think you had forgotten to get me a gift, but then surprised me by taking something out of your pocket.

You insisted I open yours first, so I did. It was a small copper and glass hanging frame. Inside were seven one penny copper coins. They all had different dates on them, one from each of the seven years we have been married. It must have taken a lot of thought and time to find them all.

You cleared your throat, looked a little sheepish. “Happy anniversary.”

I said thank you, and wanted to be grateful, but something still seemed broken between us. It felt like I had spent the evening with someone who looked and sounded like my husband, but wasn’t. You opened my hastily bought gift, and I blushed with embarrassment after all the effort you had made.

“Where did you get this?” you asked, holding the American penny up to the candlelight. It had a smiley face carved into it, next to the word “liberty.”

“Coney Island this afternoon,” I replied. “I stumbled across this arcade machine that said Lucky Pennies. The paper crane I gave you is looking a little worn out, so I thought I’d give you something new for good luck to keep in your wallet.”

“I’ll treasure them both,” you replied, tucking the penny away with your crane.

You were soon back to talking about Henry Winter again. Your favorite subject. As I half listened, I couldn’t stop thinking about October O’Brien’s untimely death, or how you seem to care more about Henry’s writing these days than you do about your own. There are plenty of horror stories in Hollywood, and I don’t mean the ones that get made into films. I’ve heard them all. Maybe I should just be grateful that you’re a screenwriter who is still getting work; it’s not always the case, and the competition is fierce. Some writers are like apples, and soon turn rotten if they don’t get picked.

You poured the rest of the wine into your glass and drank it.

“You wouldn’t worry about my career so much if you cared more about your own,” you said with slurred words, and not for the first time. I wanted to smash the bottle over your head. I love my job at Battersea Dogs Home. It makes me feel better about myself. Maybe because—like the animals I spend my time caring for—I too have often felt abandoned by the world. It’s rarely their fault that they are unloved and unwanted, just like it was never mine.

“I’m sure I could write something just as good as you, or Henry Winter for that matter—”

“Yes, everyone thinks they can write until they sit down and try to do it,” you interrupted with your most patronizing smile.

“I care more about the real world than indulging fantasies,” I said.

“Indulging my fantasies paid for our house.”

You reached for your glass again before realizing it was empty.

“Tell me about your dad,” I said, without really thinking it through. You put the glass down with a little too much force, I’m surprised it didn’t break.

“Why are you bringing that up?” you asked without making eye contact. “You know he left when I was a toddler. I don’t think Henry Winter is secretly my long-lost father if that’s where you were going—”

“Don’t you?”

Your cheeks turned red. You leaned forward before replying and lowered your voice, as if you were worried who might hear.

“The guy is my hero. He’s an incredible writer and I’m very grateful for everything he has done for me, and therefore us. That’s not the same thing as imagining him as some kind of surrogate father.”

“Isn’t it?”

“I don’t know what you’re trying to say—”

“I’m not trying to say anything, I’m telling you that I think you’ve developed some kind of emotional attachment to the man … it’s like an obsession. You’ve abandoned all your own projects to work night and day on his. Henry Winter kick-started your career when you were down on your luck, so yes you owe him some gratitude, but the way you now constantly seek his approval whenever you write something new is … at best needy, at worst narcissistic.”

“Wow,” you said, leaning back as if I had tried to physically hit you.

“You should believe in yourself enough by now to know your work is good without needing him to say so.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about. Henry has never said he likes my work—”

“Exactly! But it’s so obvious—to him and everyone else—how desperate you are for him to endorse you in some way. You need to stop secretly hoping that he will. He rarely says anything kind about another writer’s work—he rarely has a kind word to say about anything or anyone at all—just accept the relationship for what it is. He’s an author, you’re a screenwriter who adapted a couple of his novels. The end.”

“I think I’m old enough to make my own choices and choose my own friends, thank you.”

“Henry Winter is not your friend.”

When we left, I didn’t break the uncomfortable silence to let you know that I’d spotted Henry sitting a few tables away from us in the restaurant. He was hard to miss, wearing one of his trademark tweed jackets and a silk bow tie. His white hair was thinning, and he looked like a harmless little old man, but the piercing blue eyes were still the same as always. He’d been watching us the entire time we were there.

You continued to talk about him all the way to the Library Hotel, my words on the matter forgotten almost as soon as I’d said them. From the gleeful look on your face, anyone would have thought you had spent the day with Father Christmas, rather than a book-shaped Ebenezer Scrooge.

When we got back to our math-themed room, things weren’t adding up for me. I ate both the chocolates on our pillows while you were in the shower—even though I hate dark chocolate—I guess I wanted to hurt you back somehow, childish as that sounds. My phone buzzed and for a moment I thought it might be you, texting me from the hotel bathroom—nobody else sends me messages late at night. Or in the day. But it wasn’t you, it was my new friend at work saying that they missed me. The idea of anyone missing me made my eyes fill with tears. I sent them the selfie of me at the top of the Statue of Liberty and they replied straightaway with a thumbs-up. And a kiss.

You’re asleep now, but I’m awake as usual, writing you a letter I’ll never let you read. This time on hotel letterhead. A seven-year rash of resentment might be more accurate than an itch. I can’t be honest with you, but I need to be honest with myself.

I hate don’t like you right now, but I still love you.

Your wife

xx

Fullepub

Fullepub