Adam

ADAM

If every story had a happy ending, then we’d have no reason to start again. Life is all about choices, and learning how to put ourselves back together when we fall apart. Which we all do. Even the people who pretend they don’t. Just because I can’t recognize my wife’s face, it doesn’t mean I don’t know who she is.

“The doors were closed before, right?” I ask, but Amelia doesn’t answer.

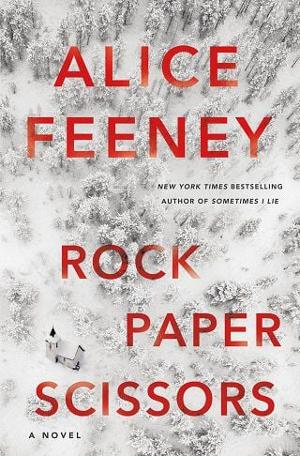

We stand side by side outside the chapel, both shivering, with snow blowing around us in all directions. Even Bob looks miserable, and he’s always happy. It’s been a long and tedious journey, made worse by the steady drumbeat of a headache at the base of my skull. I drank more than I should with someone I shouldn’t have last night. Again. In alcohol’s defense, I’ve done some equally stupid things while completely sober.

“Let’s not jump to conclusions,” my wife says eventually, but I think we’ve both already hurdled over several.

“The doors didn’t just open by themselves—”

“Maybe the housekeeper heard us knocking?” she interrupts.

“The housekeeper? Which website did you use to book this place again?”

“It wasn’t on a website. I won a weekend away in the staff Christmas raffle.”

I don’t reply for a few seconds, but silence can stretch time so it feels longer. Plus, my face feels so cold now, I’m not sure I can move my mouth. But it turns out that I can.

“Just so I’ve got this clear … you won a weekend away, to stay in an old Scottish church, in a staff raffle at Battersea Dogs Home?”

“It’s a chapel, but yes. What’s wrong with that? We have a raffle every year. People donate gifts, I won something good for a change.”

“Great,” I reply. “This has definitely been ‘good’ so far.”

She knows I detest long journeys. I hate cars and driving full stop—never even took a test—so eight hours trapped in her tin-can antique on four wheels, during a storm, isn’t my idea of fun. I look at the dog for moral support, but Bob is too busy trying to eat snowflakes as they fall from the sky. Amelia, sensing defeat, uses that passive-aggressive singsong tone that used to amuse me. These days it makes me wish I was deaf.

“Shall we go inside? Make the best of it? If it’s really bad we’ll just leave, find a hotel, or sleep in the car if we have to.”

I’d rather eat my own liver than get back in her car.

My wife says the same things lately, over and over, and her words always feel like a pinch or a slap. “I don’t understand you” irritates me the most, because what’s to understand? She likes animals more than she likes people; I prefer fiction. I suppose the real problems began when we started preferring those things to each other. It feels like the terms and conditions of our relationship have either been forgotten, or were never properly read in the first place. It isn’t as though I wasn’t a workaholic when we first met. Or “writeraholic” as she likes to call it. All people are addicts, and all addicts desire the same thing: an escape from reality. My job just happens to be my favorite drug.

Same but different, that’s what I tell myself when I start a new screenplay. That’s what I think people want, and why change the ingredients of a winning formula? I can tell within the first few pages of a book whether it will work for the screen or not—which is a good thing, because I get sent far too many to read them all. But just because I’m good at what I do, doesn’t mean I want to do it for the rest of my life. I’ve got my own stories to tell. But Hollywood isn’t interested in originality anymore, they just want to turn novels into films or TV shows, like wine into water. Different but same. But does that rule also apply to relationships? If we play the same characters for too long in a marriage, isn’t it inevitable that we’ll get bored of the story and give up, or switch off before we reach the end?

“Shall we?” Amelia says, interrupting my thoughts and staring up at the bell tower on top of the creepy chapel.

“Ladies first.” Can’t say I’m not a gentleman. “I’ll grab the bags from the car,” I add, keen to snatch my last few seconds of solitude before we go inside.

I spend a lot of time trying not to offend people: producers, executives, actors, agents, authors. Throw face blindness into that mix, and I think it’s fair to say I’m Olympian level when it comes to walking on eggshells. I once spoke to a couple at a wedding for ten minutes before realizing they were the bride and groom. She didn’t wear a traditional dress, and he looked like a clone of his many groomsmen. But I got away with it because charming people is part of my job. Getting an author to trust me with the screenplay of their novel can be harder than persuading a mother to let a stranger look after their firstborn child. But I’m good at it. Sadly, charming my wife seems to be something I’ve forgotten how to do.

I never tell people about having prosopagnosia. Firstly, I don’t want that to define me, and honestly, once someone knows, it’s all they want to talk about. I don’t need or want pity from anyone, and I don’t like being made to feel like a freak. What people don’t ever seem to understand, is that for me, it’s normal not to be able to recognize faces. It’s just a glitch in my programming; one that can’t be fixed. I’m not saying I’m okay with it. Imagine not being able to recognize your own friends or family? Or not knowing what your wife’s face looks like? I hate meeting Amelia in restaurants in case I sit down at the wrong table. I’d choose takeout every time were it up to me. Sometimes I don’t even recognize my own face when I look in the mirror. But I’ve learned to live with it. Like we all do when life deals us a less than perfect hand.

I think I’ve learned to live with a less than perfect marriage, too. But doesn’t everyone? I’m not being defeatist, just honest. Isn’t that what successful relationships are really about? Compromise? Is any marriage really perfect?

I love my wife. I just don’t think we like each other as much as we used to.

“That’s nearly all of it,” I say, rejoining her on the chapel steps, saddled with more bags than we can possibly need for a few nights away. She glares at my shoulder as if it has offended her.

“Is that your laptop satchel?” she asks, knowing full well that it is.

I’m hardly a rookie so I can’t explain or excuse my mistake. I imagine Amelia pulling a Go to Jail–card face. This is not a good start. I will not be allowed to write this weekend or pass Go. If our marriage were a game of Monopoly, my wife would charge me double every time I accidentally landed on one of her hotels.

“You promised no work,” she says in that disappointed, whiney tone that has become so familiar. My work paid for our house and our holidays; she didn’t complain about that.

When I think about everything we have—a nice home in London, a good life, money in the bank—I think the same thing as always: we should be happy. But all the things we don’t have are harder to see. Most friends our age have elderly parents or young children to worry about, but we only have each other. No parents, no siblings, no children, just us. A lack of people to love is something we’ve always had in common. My father left when I was too young to remember anything about him, and my mother died when I was still in school. My wife’s childhood was no less Oliver Twist, she was an orphan before she was born.

Bob saves us from ourselves by growling at the chapel doors again. It’s strange, because he never does that, but I’m grateful for the distraction. It’s hard to believe he used to be a tiny puppy, abandoned in a shoe box and dumped in the trash. Since then he has grown into the biggest black Labrador I have ever seen. He has a collection of gray hairs on his chin these days, and walks more slowly than he used to, but the dog is the only one still capable of unconditional love in our family of three. I’m sure everyone thinks we treat him like a surrogate child, even if they are too polite to say so. I always said I didn’t mind not having a real one. People who don’t get to name their children get to name a different future. Besides, what’s the point in wanting something you know you can’t have? Too late for that now.

I don’t normally feel forty. I sometimes struggle to understand where the years went and when I transitioned from boy to man. Maybe doing a job that I love has something to do with that. My work makes me feel young, but my wife makes me feel old. The marriage counselor was Amelia’s idea, and this trip was theirs. “Call me Pamela,” the so-called expert, thought a weekend away might fix us. I guess all the weekends and evenings spent together at home were null and void. Weekly visits to share the most private corners of our lives with a complete stranger cost more than just the extortionate fee. For that money, and several other reasons, I repeatedly called the woman Pammy or Pam every time we met. “Call me Pamela” didn’t like that, but I didn’t like her much so it helped make things even. My wife didn’t want anyone else to know that we were having problems, but I suspect some might have noticed. Most people can see the writing on the wall, even if they can’t always read what it says.

Can a weekend away really save a marriage?That’s what Amelia said when “Call me Pamela” suggested it. I don’t think so. Which is why I came up with my own plan for us long before I agreed to hers. But now we’re here … climbing the chapel steps … and I don’t know if I can go through with it.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” I say, stopping just before going inside.

“Yes. Why?” she asks, as though she can’t hear the dog growling and the wind howling.

“I don’t know. Something doesn’t feel right—”

“This isn’t a horror story written by one of your favorite authors, Adam. This is real life. Maybe the wind blew the doors open?”

She can say what she likes, but the doors weren’t just closed before. They were locked and we both know it.

We find ourselves in what posh people call a boot room and I put the bags down. A puddle of melting snow forms around my feet. The flagstone floor looks ancient, and there is built-in storage along the back wall with rustic wooden cubbyholes designed for boots. There are also rows of hooks for coats, all of which are empty. We don’t remove our snow-covered shoes or jackets. Partly because it is just as cold in here as it was outside, but also perhaps because it still seems uncertain whether we are staying.

One wall is covered in mirrors, small ones, no bigger than my hand. They are all odd shapes and sizes with intricate metal frames, and have been hung haphazardly in place with rusty nails and rustic twine. There must be fifty sets of our faces reflected back at us. Almost as though all the versions of ourselves we became to try and make our marriage work, have gathered together to look down on who we’ve become. Part of me is glad I can’t recognize them. I’m not sure I’d like what I saw if I could.

That isn’t the only interesting feature of interior design. The skulls and antlers of two stags have been mounted like trophies on the farthest whitewashed wall, with four white feathers protruding from the holes where their eyes must once have been. It’s a little strange, but my wife takes a closer look and stares in fascination, like she’s visiting an art gallery. There is an old church bench in the corner that attracts my attention. It looks antique and is covered in dust, as if nobody has been here for a very long time. As first impressions go, this isn’t a great one.

I remember the way Amelia and I used to be together, in the beginning. Back then, we just clicked—we loved the same food, the same books, and the sex was the best I’d ever had. Everything I could and couldn’t see about her was beautiful. We had so much in common and we wanted the same things in life. Or at least, I thought we did. These days she seems to want something else. Maybe someone else. Because I’m not the one who changed.

“You don’t need to draw in the dust to make a point,” Amelia says. I stare at the small, childish, smiley face she is referring to on the church bench. I hadn’t noticed it before.

I didn’t draw it.

The large wooden outside doors slam closed behind us before I can defend myself.

We both spin around, but there is nobody here except us. The whole building seems to tremble, the tiny mirrors on the wall swing a little on their rusty nails, and the dog whimpers. Amelia looks at me, her eyes wide, and her mouth forming a perfect O. My mind tries to offer a rational explanation, because that’s what it always does.

“You thought the wind might have blown the doors open … maybe it blew them shut,” I say, and Amelia nods.

The woman I married more than ten years ago would never believe that. But these days, my wife only ever hears what she wants to hear, and sees what she wants to see.

Fullepub

Fullepub