Chapter Six

A fter that first afternoon they spent together in the parlour, something of a routine was quickly established at Hayton Hall. Sir Samuel would spend the morning attending to his duties on the estate, leaving Hope to rest in her bedchamber. Around noon, Maddie would serve her luncheon in her room and then help her to dress before Sir Samuel arrived to collect her and carry her down to the parlour for tea.

If Hope was honest with herself, she'd already begun to look forward to their meetings, perhaps more than she should. After all, every conversation they had carried a risk—a risk that she might accidentally reveal some detail about her real self, or a risk that she might say something to provoke Sir Samuel's suspicions about the authenticity of the story she had told him.

Despite these risks, Hope did her best to immerse herself in the role she had created, allowing herself to enjoy the fine dresses she wore, the comfortable sofa she sat upon and the quality tea she sipped while getting to know her host better. Sir Samuel seemed to understand that she did not wish to talk much about herself. Since she'd politely refused to answer his enquiry about where she was from, he had not asked her anything specific about her life at all.

Instead, he engaged her on less contentious topics, everything from the minutiae of the day to discussions about favourite pursuits. Hope learned that he'd travelled widely, that his knowledge of the Continent, of its different countries and cultures, was second to none. She found his descriptions of all that he'd seen fascinating; from lakes flanked by towering mountains in Switzerland to crowds of boats on the Venetian lagoon, it was as though he was revealing new worlds to her through words alone.

‘You are fortunate to have seen so much of the world,' she'd mused one afternoon as he concluded one of his tales. ‘Especially with an estate to manage.'

‘Well, of course, all of this took place before I had such responsibilities,' he'd replied, giving her an odd, strained look.

Realising he must have been referring to the time when his father still lived, she'd glanced at the walking cane she'd placed beside her, suddenly struck by all that had passed from father to eldest son. ‘It must be a strange thing to inherit all of this,' she'd remarked, waving a hand delicately about her. ‘For all the security it surely brings, it must also place limitations upon a gentleman. You cannot freely do as you please when you have duties to your family, your land and your tenants.'

Sir Samuel had given her a tight smile. ‘I hardly think any gentleman born into comfort and wealth has any right to complain about his lot, however much he might wish to.'

His reticence had made Hope grin. ‘Surely everyone has the right to complain sometimes,' she'd replied. ‘It strikes me, sir, that running an estate well is very hard work.'

‘Indeed it is,' he'd agreed, ‘and not only for gentlemen, as you may discover, should you one day marry and find yourself the mistress of some grand house with many acres attached to it.'

Her smile had faded quickly at that. ‘That seems unlikely,' she'd replied, grappling for the right answer, the one which Hope Swynford would surely give. ‘My uncle all but dragged me to the border to wed a stranger,' she'd reminded him. ‘He might not have succeeded, but I hardly think that detail will matter. I am doubtless ruined in the eyes of society.'

She'd half expected Sir Samuel to argue, but instead he had agreed. ‘Polite society is apt to condemn, and apt to make ill-founded judgements upon others,' he'd remarked with such resignation that Hope could not help but wonder if his words had been provoked by more than her retort.

‘Oh, I almost forgot,' he'd said, swiftly changing the subject as he lifted a pile of books off the nearby table. ‘All that talk about John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford the other day prompted me to remember these books. Mr Hume's A History of England . I thought they might help you to pass the time while you convalesce. That is, if you have not already read them.'

Hope had shaken her head, accepting the six volumes as Sir Samuel handed them to her. ‘No, I confess I have not read them,' she'd replied as casually as she could manage. Again, she'd no idea if a woman like Hope Swynford would be expected to have read such books or not.

To her relief, Sir Samuel had seemed not at all perturbed by her admission, which was just as well because Hope had felt unsettled enough for the two of them. As much as she enjoyed Sir Samuel's company and conversation, it was moments like that which reminded her of all she was pretending to be, and all that she was really not. Sir Samuel was a learned gentleman, well-tutored and well-travelled. By contrast, Hope was fortunate that she could read at all; as a girl, she'd been taught her letters by her mother, but they had not owned books like the ones Sir Samuel had given to her. As a woman, she read broadsides and chapbooks, and perhaps the occasional well-thumbed novel which had been passed between the actresses.

Life had taught Hope most of the lessons she knew, and latterly, the theatre had been her schoolroom. Indeed, the theatre was the one area in which she could perhaps match Sir Samuel's knowledge, albeit whilst implying that she'd become acquainted with Shakespeare's plays from a seat in a box at Covent Garden or Drury Lane, and not because she'd spoken his words on stage at Richmond's Theatre Royal.

Unfortunately, it seemed to Hope that fate had more discomfiting moments in store for her. Today, as they rose to leave the parlour, Sir Samuel suggested that they dine together in the evening for the first time. Hope was reluctant; until now she'd eaten her evening meal in her bedchamber, under Maddie's watchful eye but with no expectation of displaying the proper manners or refinement. She knew enough about the habits of the wealthy to know that dining formally with Sir Samuel would be an entirely different matter, and one which she was not confident she would manage. Indeed, the thought of sitting at his fine table, completely lost in the face of all those dishes and all that cutlery, made her feel quite sick.

‘I'm afraid my appetite is not as it should be,' she explained, trying her best to thwart him as gently as she could. ‘I do not think I could manage it.'

‘I do not propose we get through a pile of game and a mountain of jelly by ourselves,' he replied. ‘Indeed, most evenings I sit down to a bowl of soup followed by a small plate of fish and vegetables.'

That admission caught her by surprise. ‘That is what I am served most nights, in my room.'

‘That's right, because that is what my cook has made for us both,' Sir Samuel answered with an amused smile. ‘You look startled, Miss Swynford.'

She shook her head. ‘I do not know why, I just had not imagined you were eating the same meal as me.'

He began to laugh. ‘Oh, heavens! Now I'm concerned you must have imagined me dining downstairs upon fifteen courses while Madeleine served you meagre soup and fish. I'm a country gentleman, Miss Swynford, not the Prince Regent.'

Hope felt her cheeks begin to flush. ‘I can assure you, sir, I did not think that. It is just that I have found my meals very restorative and I assumed they had been served to me for that reason.'

Sir Samuel nodded. ‘Yes, and what is good for you is also good for me. I prefer simple, hearty fare. I am not a great enthusiast for rich sauces or heavy puddings.'

‘Except cake,' she countered. ‘One of the two best things in life, if I recall.'

He grinned at her. ‘That's right. Now then, on the promise of a small, simple meal, will you dine with me this evening, Miss Swynford?'

Hope felt her hesitation melt in the face of his convivial persuasion. That was something else she'd observed about Sir Samuel—what he had in learning was easily matched in charm and good humour. She found herself reflecting momentarily upon his qualities, his affability and aptitude for conversation, and contrasted that with what she knew of his life at Hayton Hall, alone and unwed. She wondered why that was, wondered too if it had anything to do with the remark he'd made just days ago about matters of the heart and their consequences. Then she pushed the thought aside, deciding it was none of her business.

Instead, she returned his smile, knowing that whatever misgivings she still had, there was only one answer to his invitation that she could possibly give. ‘That sounds lovely, Sir Samuel.'

Samuel took a mouthful of his evening meal, believing it to be the best mackerel he'd ever tasted. Weeks of dining alone had led him to become largely disinterested in what was on his plate, the business of eating having become a mere necessity rather than a pleasure. This evening he was reminded just how much he enjoyed dining in company. He'd been delighted when Miss Swynford had agreed to join him, although acknowledging this delight had made him feel instantly guilty as he was forced to remember that he was enjoying her company under false pretences. That he was allowing this lovely young lady to believe she was dining with Hayton's baronet. Swiftly he had buried the thought, reminding himself of the reason for his ongoing deception. It made Miss Swynford feel safe and protected. That alone made the lie a worthy one, didn't it?

He'd wrestled with that question, and his conscience, ever since that moment at the bottom of the staircase when he'd made the decision to hold his tongue. He'd wrestled too with the uncomfortable knowledge that as honourable as his intentions were in keeping the truth from her, maintaining the deception had also saved him from seeing her evident disappointment when she learned who he truly was. He had to admit to himself that whilst his desire to make her feel secure with him was paramount, he was still allowing his wounded pride to rule his head, at least in part.

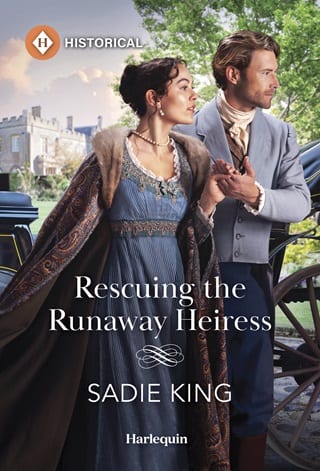

Across the table, Miss Swynford caught his eye and he offered her a smile. Like him, she'd dressed for dinner, the cream day dress she'd worn earlier now replaced by a very becoming periwinkle blue gown. Several times his gaze had been drawn to how the colour contrasted so sharply with her dark hair, how the silk fabric flattered her slender form, before he reminded himself that he had no business admiring her. Especially not when it was another of Rosalind's dresses that she wore.

Miss Swynford returned his smile shyly, before taking a tentative sip of the fine claret he'd had Smithson fetch from Hayton's cellars. She seemed on edge tonight, surveying the food and drink before her with wide eyes, consuming them slowly and deliberately, as though she was unsure of herself. As though she was unsure of him.

Samuel felt his smile fade, gripped now by the worrying thought that he might be responsible for her apparent discomfort, that perhaps dining together like this had been a step too far. However compelling the reasons were for her to remain in his home at present, she was nonetheless an unchaperoned, unmarried woman, convalescing in close confinement with an unmarried man. Perhaps she'd been able to countenance tea and cake in the afternoon light of a parlour, but the presence of claret and candles as day faded to night felt too intimate. He had not considered it like that before but, now that he did, he could see how dining like this could be construed in that way. How it might give rise to concerns about his intentions, and just how dishonourable he might in fact be. He reminded himself again of all that she'd endured of late. Certainly, her wicked uncle and his equally dreadful conspirator had given her no reason to trust a gentleman.

‘I hope you will forgive me for asking you to join me this evening, Miss Swynford,' Samuel began, possessed now by the urge to say something, to explain himself.

She looked up from her plate, fork poised. ‘Forgive you?'

‘Indeed, it was very selfish of me. I occupied you for much of the afternoon in the parlour, and ought to have left you to rest this evening.'

She wrinkled her brow at him. ‘Do I look tired, sir?'

‘Well, no, of course not...'

She gave him another of those small smiles. ‘Then all is well. I will be sure to say, if I wish to retire.'

‘Yes, of course, very good.' He paused, momentarily unsure how much more he wished to say, before swallowing his pride and adding, ‘I would just like to assure you that I have only the most honourable and gentlemanly intentions in inviting you to dine with me. I merely felt it would be nice for us both to have some company during dinner, that is all.'

Miss Swynford sipped her wine again, lingering somewhat over it, and he could tell that she was considering his words. Inexplicably, his stomach started to churn, and he began to regret eating that mackerel quite so enthusiastically. He would have to ask Smithson to have the cook prepare for him some of that sweet ginger drink she always swore aided digestion.

‘I am relieved to hear it, Sir Samuel,' she replied at length. ‘I cannot tell you all the wild thoughts I had been entertaining since we sat down to our soup.'

Samuel felt his heart skip a beat. ‘Really?'

The horror on his face must have been comical, because Miss Swynford began to laugh. ‘No, of course not,' she said between chuckles, clearly trying to retain a modicum of self-control. ‘I cannot think why you would even feel the need to clarify your intentions, sir. I know we have only known one another for a matter of days, but you have given me no reason to think of you as anything other than the very best of gentlemen.'

He raised a smile at her compliment, even as it made him feel utterly wretched. Would she still think that if she knew he was not really Hayton's baronet? ‘I only wished to put you at your ease,' he said after a moment. ‘I am sorry to observe it, but you looked uncomfortable from almost the moment you sat down to dine.'

In the dim light offered by the candles and the coming dusk outside, Samuel was sure he saw her expression darken. ‘I am not used to dining in this manner,' she replied quietly, ‘with such fine food and drink, such civilised company.'

He frowned. ‘What do you mean?' he asked, a furious heat growing in his chest as his mind raced to contemplate all that her words might imply. ‘What happened to you, Miss Swynford? In what manner was this uncle of yours keeping you?'

She shook her head gently, declining to answer. When she looked up, her expression had brightened once more. She reached for her glass again. ‘The wine really is very good, sir,' she remarked, taking a sip and, he suspected, collecting herself. Something was amiss, but he was damned if he could fathom what it was.

He nodded, lifting his glass in agreement. ‘A Bordeaux wine, and one of my particular favourites, although I only indulge when in company. Drinking such fine wine alone always seems rather a waste,' he added.

‘I must confess to wondering why you are alone here, Sir Samuel,' Miss Swynford replied, meeting his eye. ‘Forgive me, but you must surely be one of Cumberland's most eligible gentlemen.'

Her directness took him aback. ‘I'm not sure about that...' he began, before realising that he had no idea what to say. How could he possibly explain himself? He did not want to let yet more falsehoods fall from his tongue, to portray himself as some sort of humourless baronet, so committed to managing his estate that he had not yet troubled himself to find a wife. Yet he could not bring himself to tell her the truth either, that he was a lesser prospect, a younger brother, a recent reject on Cumberland's marriage mart because he had not quite passed muster. That final fact, in particular, was too humiliating an admission to contemplate.

It was clear from the expression on her face that Miss Swynford had seen his discomfort. ‘I am sorry,' she said softly, before he could settle upon an explanation. ‘It is none of my business. In any case, I dare say it will not be long before I hear of your marriage to some well-connected society beauty with a large fortune.'

Samuel gave a wry chuckle. ‘She sounds...intimidating.' His smile faded. ‘To be frank, I think I'd prefer genuine companionship, Miss Swynford. Wealth and connections might matter a great deal to some people, but not to me. If I marry, I would rather it was for love than status.'

Miss Swynford's eyes seemed to search his, as though she was surprised by this admission, as though she was trying to determine if he was in earnest. Truly, she must have only ever been acquainted with the most dreadful gentlemen if she could be so astonished by his heartfelt confession. Then again, hearing those words fall from his own lips had come as something of a surprise to him too. He'd heard the sharp edge in his own voice as he'd spoken about other people's considerations, and the frankness when he'd confessed his own.

He had not meant to be quite so blunt, to speak of marriage and love—two things he'd sworn off for now, and for very good reasons. Truly, what had come over him lately? Clearly, those smouldering embers of the hurt and humiliation he'd experienced had been given cause to reignite. Or perhaps, he considered, they'd never quite ceased to burn in the first place.

Samuel shook his head at himself. ‘Forgive me...'

The sound of the door opening caused them both to startle and Samuel turned to see Smithson burst into the dining room, somewhat breathless, his cheeks flushed.

‘Sir, I am sorry to disturb you at dinner,' the butler began. ‘But I need to speak with you urgently.'

Samuel pushed back his chair impatiently, nodding an apology to Miss Swynford before turning to regard the older man. ‘What on earth is amiss?' he asked as he strode towards him. ‘Has there been some accident? Is it one of the servants?'

‘No, sir.' Smithson spoke in a hushed tone, giving Miss Swynford a worried glance. ‘No accident. But I must tell you that there is a carriage coming up the drive. A carriage I do not recognise. Someone is coming to call at Hayton Hall, sir. Tonight.'

Fullepub

Fullepub