Chapter 1: John

If I could burymyself in the North Carolina soil, made for dense forests of trees, I would. Anything to get out of meeting Aaliyah's new boyfriend. He has the hair on the back of my neck standing at attention. My leg craves to bounce in place, but I sit stiffly on his too clean couch.

"Aaliyah says you're really into photography," Gonzales says with an easy smile that reminds me he's a psychology major.

I feel like a small child sitting across from him.

There's a beer can in front of me gathering condensation, but none of my fingerprints, and I feel like Gonzales has been taking note of it. It's a local brew I don't recognize, but I'm sure my pa would know the name.

Aaliyah raises her eyebrow at me. It's a sign to behave, it's a sign to breathe. It's both because she knows I hate Gonzales, even though I've never met him until now.

"Is that a bad question?" he asks when my silence goes on for too long.

It isn't that it's a bad question necessarily. It's that the question involves telling him about my dad and about how young and na?ve I once was. I began taking photos to spare my dad from missing out on things while he was away on deployment. Jokes on me, of course, because he ended up missing everything.

"Just collecting memories," I finally tell him, sitting back and smiling calmly.

The entire fa?ade only shows what I want it to. Let him falsely think I'm sentimental and not masochistic.

"Okay," he replies, mouth quirked at the corner to let me know he's letting me get away with my half-truth. Psych majors are a burden to society. I've told my therapist as much.

Aaliyah sees right past our cock show and diverts Gonzales's focus onto her as she talks about my photography. Nothing divulging; just small talk between new acquaintances that she shoulders so I don't have to.

I exhale the weight of dealing with Aaliyah's new boyfriend. The pit in my stomach is heavy, feeling nothing but anger. It's good that Aaliyah is dating, it's good that she feels comfortable enough about our friendship that she can bring other people into it. At least, that's what my therapist says. I see it as another way for the universe to prove no one will stay by my side.

There have been two people in my life that have unexpectedly slipped into the circle of things I care about. Aaliyah is one of them. That's the only reason I'm even here, trying to not let her slip through my fingers before it's too late.

I roll my shoulders, trying to push back my toxic thoughts and discomfort.

Unfortunately, I can see why Aaliyah likes him. He looks like an uncut stone, sturdy and reliable in a way that her family has never been. He looks like he could cut out our hearts neatly and put them on a display case. Aaliyah likes that sort of honesty and openness in a man. I detest it.

"Are you planning on taking photos for the Trans Rights Rally? It's all Aaliyah talks about," Gonzales says earnestly, and I immediately fight back an eye roll.

Aaliyah told me they met in a local bookstore, hands touching as they both reached for a memoir in the queer section. Their meet-cute does little to sway my opinion of him. For all I know, he could've been grabbing it for a report on why being queer is a mental illness.

"Of course it's all I talk about," Aaliyah starts. "How could you not think about how people in our country are fighting for their rights?"

"Yeah, I know what you mean. My mom came here looking for the American dream and... well, life hardly works out that way for migrants," Gonzales says, his thick eyebrows turning down into a frown. "Politicians are just uneducated figureheads. I've taken a few queer education courses for the psychology track, since one day it'll be my job to approve folks for gender affirming care and—" he sighs. "If they just took an introductory course, I feel like things would be different."

I hum in agreement, but in reality, I'm exhausted. Aaliyah and I have spent the entire beginning of the semester trying to organize this rally. There are schedules to consider and approval to be obtained. I've been involved in as much activism as I can on campus these past two years. Being an activist has only resulted in single-minded conversations, where everyone postures in a game of trying to prove themselves the best ally. It's as if gaining my approval means their own bigotry is excused.

I'm sure Gonzales is just like everyone else trying to earn his gold star. His apartment is uncomfortably clean and tidy. The fridge is stocked with nice beer and fresh veggies. If this is what college men were really like, I might have actually dated someone by now.

His pristine brown-nosing still makes me feel underdressed in my oil-stained shirt, but it was either this or a date shirt. I try to only use those late at night when the loneliness of sharing a bed solely with textbooks sets in and Grindr starts to look like a good option.

I eye the unopened beer on the table with distaste and think about my dad, who I should've already been with by now. I've been here too long watching Gonzales and Aaliyah snuggle up together.

"Well, it's been great meeting you," I lie. "But I have to head out." I stand and clasp hands with Gonzales.

"Hold on, I'll walk you out," Aaliyah says, standing up quickly.

She walks me all the way to my car, which by this point is basically a family heirloom. The clutch sticks between first and second, I have to pull the handle twice before the driver side door even opens, and the seats have stains of my father's past indiscretions, but it's my car. My dad's car. The car. The Love Family Car.

"He's a good guy, John," Aaliyah says, seeing past everything everyone else does.

I shrug. "He seems like a guy you'd like." I turn and give her a hug, minding her afro that fills me with envy. Even in the North Carolina humidity, it never falters.

"Ringing approval," she says, voice dripping with sarcasm.

Aaliyah and I have known each other since our freshman year at Duke University—a chance encounter during club sign ups where we both reached for the pen at the same time. The rest is a series of late nights studying with breaks in between to decorate protest signs. Neither of us have the best relationships with our families, but we've done our best to look out for each other.

"He's a senior, Liyah. He's just going to be gone next year." I don't tell her I also don't trust him. She knows that already. I don't trust people further than I can throw them. "But, if he makes you happy..."

She nods and rests her head against my shoulder.

"A'ite," she mumbles against me, using a word she's stolen from my own southern vocabulary. "Thanks for coming. I know you've got other things to be doing."

"Work," I tell her with an eye roll, even though we both know that's only a half-truth. I already worked my double shift.

She turns away, back to Gonzales's, and I pull the car door handle twice until it pops open.

The car smells like air fresheners, so much so that it's nearly pungent, in an attempt to cover the smell of spilled booze that's accumulated over the years. It's worse as I press my forehead against the steering wheel, nose too close to the scent clipped onto the vents.

"Please don't be dead. Please don't be dead. Please don't be dead." But after repeating the mantra enough times, it begins to blend and go fuzzy at the edges until I'm not sure it doesn't sound like "please be dead".

I start the car and the engine roars to life. Even if I've never gotten this old gal a paint job, it's not the car that I'm worried about dying; she still runs smoother than butter. I start my long and quiet drive to my alcoholic dad's mobile home, filled with broken memories of absent parents.

North Carolina doesn't careabout what weather it brings. It doesn't care to make the beaches bright and sunny throughout the months when tourists flock in, or make the mountains snow covered for ski season. Sometimes, in the summer, when I'm trying to get my dad out of the house and into the sun, North Carolina will choose that day to be overcast—trapping in the humidity and chasing away any hopes of Vitamin-C. Sometimes, in the winter, that same humidity will spike, and I'll feel like my shirt has been soaked into my skin, only to then freeze against my already aching body.

Every summer, no matter if the highways are being expanded or if the campuses are suddenly desolate, the cicadas crawl out of their trees and scream all day in search of a mate, until the fireflies replace them at night. Although, there have been less and less of their light each year. Every autumn, the trees in the Appalachians blossom across the mountains in yellows and oranges that send people flocking to take photos, myself included. Every winter, we play a game of cat and mouse with the snow to see if it'll come—it hardly ever does in Durham.

Every spring, it rains.

It rains so abruptly and heavily that sometimes it'll catch you by surprise while driving on I-85. The downpour can be so aggressive that the hood of the car isn't even visible. It was one of these storms that killed my mother over eleven years ago.

North Carolina doesn't care about emotions. Because, despite the ocean of wonder and mystery—its cities brimming with excitement and opportunity, its mountains vivid with life and adventure—it still didn't hold me, not in the great branches of the trees above me as I cried. Its roots never erupted from the ground to take me away, like I so often begged. The leaves never fell in quantities so great that it would cover the tears I had shed.

It's because I was raised by North Carolina that I try to care so little. A false attempt to be like the enigma of beasts that crawl in between the dark shadows cast by trees. Like the tumultuous weather that rains and cries all at once before suddenly stopping, hiding it all behind a sunny sky. I am the years and years of war and blood held in this land.

I don't blame my parents for growing up halfway between a trailer home and a military base. I don't blame my dad for joining the army in an effort to better our lives so we could get out of that trailer home. I don't blame my mom for dying in a tragic car accident while my dad was across the world.

That doesn't mean they're completely blameless for how shit my childhood was.

Addiction is a disease. Logically, I understand that, but it's different when you're ten years old staring at your sweaty, puke-covered dad laying on the floor. The same floor where your recently deceased mom once twirled around in time with the spinning vinyl records.

His temporary leave was supposed to be about handling the situation and taking me back with him until his contract was up. Instead, I had to handle him. Only to be abandoned to the lonely trailer and a wallowing aunt as he finished up his contract, alone and drunk.

Thick branches of trees—an eternal prison of bad memories—open up to a trailer park, gravel crunching under my already bare tires.

The trailer still has its lights on when I pull up making a shiver run down my spine.

After my dad's contract was up and we returned to North Carolina, I knew exactly what I was coming home to every day—an empty house with the promise of booze behind every corner. My dad used to come home late at night, if at all, and pass out on the couch or call for me as he puked in our kitchen sink, only to rinse and repeat every night after he got off work.

Now he's home every day, except for when his AA buddy drives him to their shared job. When I open that door, he could still be puking or passed out on the couch—or worse. Now, it isn't because he's drunk. It's because he spent so much time being drunk that he's permanently destroyed his liver.

It always takes me a minute to gather the courage to open the door and I avoid it by walking over to the old 1969 Camaro—once bright red, now a rusted brown—and lean against it.

There's a couple of empty bottles of booze sitting in it. But once, it was our dream car. My dad bought it before his final deployment. He'd promised me, my chubby face in his cupped hands, that when he came back, we'd fix it up. He just didn't know he would come back to an empty house, and I would come back from my aunt's house to an empty father.

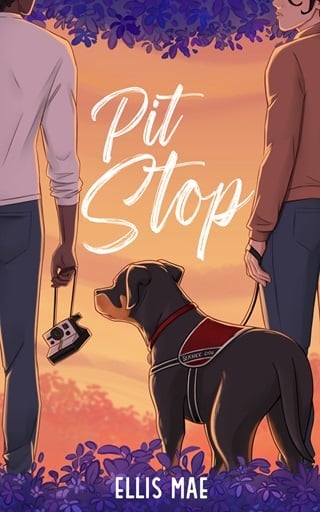

Staring at the broken shambles of my childhood, I snap a photo on the other camera I carry with me—a dinky little Polaroid. It's a continuation of my masochistic streak that reminds me that this is all that's left.

Steeling myself, I walk up the stairs and through the door. My dad is on the couch, sipping on a bottle of sparkling water. I heard they're good for staving off the urge to drink and now we have enough supplies to last us a year.

"How was your night?" he asks, looking back at me.

This is when a good son smiles. This is when a good son says, "thank you for leaving the lights on and waiting to make sure I got home safe." This is when a good son gives his ailing father a hug.

I'm not a good son.

But only because my dad was never a good father.

"It was fine," I respond, going to the fridge and counting the meal prepped dishes still left.

Every Sunday, I make my dad's food for the week and try to gauge what he can actually stomach on his weak appetite. It'd be easier if he just told me.

My dad calls me from the couch, where he's cradled in his cable knit cardigan, and pats the spot beside him. I reluctantly sit beside him.

"You eat enough?" I ask as SportsCenter blares on the TV.

"Yeah," he says proudly.

I let the silence between us hold his lie so I don't have to.

He sighs.

I sigh.

"I took my meds but it's still hard to eat," he tells me, excitement drained from his voice. "Sorry," he adds quietly.

I pat his leg. It's frail beneath my palm. "I know, dad. At least you ate something. I have work in the morning."

Despite everything, it still hurts to see him as ill as he is.

"Okay. Take the keys to bed with you or I'll run to the ABC," he says. "I had a bad customer today and it's been really gettin' to me," he explains.

I look down at him as I stand from the couch. His brown eyes are the same as mine, full of grief and sorrow for a life that could've been.

When I was little, I looked like my mom. The same round face and untamable head of spiral curls. Now I look like my dad. I don't know which is worse.

"A'ite," I say, taking the keys from him. My tongue rolls in my mouth uncomfortably. I know I'm supposed to say something supportive, but I wouldn't even know where to start.

He gives me a sad smile and I walk away from him to my bedroom. Unlocking it, I immediately collapse into bed, too tired to care.

It's too late to try and give a shit. It's always been too late.

Isamu

The Raleigh/Durhaminternational airport is surprisingly small for being an academic hub, since it only takes Inu and I a few dozen yards before we're at the escalator for the exit gates. I'm thankful for the short distance as I shift my backpack and medical bag to alleviate pressure off my prosthetic limb.

Inu presses against me calmly, unaffected by the grinding metal of the escalator below us.

Despite that I just spent two weeks learning Inu's commands beside her trainers, her behavior still impresses me. A service rottweiler made for sturdiness that I've named Inu, much to Japanese parents' horror.

Inu must feel my gaze on her because her heavy brown eyes look up into my nearly black ones. I rub her head as we exit the airport and enter a muggy North Carolina day—typical for the area but unwelcome nonetheless.

I had to wait a few months after my medical separation from the army to get her because I went to visit my mom in Japan. Now I'm back, and I've trapped Inu with me in a city where no one even needs me anymore. My mom is across the world, my dad is selling our childhood home to join her, and my best friend is less than a year from graduation.

"No mames. Look what the devil dragged in," Gonzales shouts, arms wide open from where he's been loitering in the arrival lane.

"Holy shit," I call out, grin splitting my face as I move forward and clutch Gonzales tightly in my fatigued arms—traveling on a plane is truly the worst. Between the heavy medical bag and swelling of my residual limb from altitude, I think I'll be swearing off planes for the rest of my life.

I hold onto Gonzales like a lifeline. Like a long-lost brother.

"Fuck, did you get taller?" I clasp his shoulder, ashamed I have to look so far up to meet his eyes.

"Nah, Isa, I think you got shorter. You sure you didn't lose both legs?"

I cackle as he takes my medical bag off my shoulder. He groans under the weight of it before turning back toward us.

"Is this her?" he whispers with reverie, lowering himself to eye level with Inu, who obediently ignores him.

When the VA said I qualified for a service animal because of my above knee amputation and PTSD, both resulting in a heart condition, I figured I'd get a labrador to carry my ass home from a drunken night out. Turns out, they kind of throw you into group therapy during your two years before medical retirement to see if you've even got the mental functionality to be worthy of a dog.

"No. This is just some dog I picked up in a dark alley of Shibuya." I give him a deadpan look and drop my backpack between them. "Yeah, this is Inu. Don't pet her though."

Gonzales lets out a snort of laughter. "I thought Takeo was joking when he said you named your dog ‘Dog'."

I shrug and open the back seat of Gonzales's flashy muscle car, then usher Inu in before opening the passenger door for myself. I don't know much about cars, but I know a Mustang when I see one and I know a flashy car if it's got electric blue racing stripes on white like this.

"Where'd you get the money for this bad boy?" I ask, staring at the interior—too flashy for me to understand.

"Sued my mom after my sister moved out," he grumbles while he loads my bag into the backseat. "Sorry, didn't want to bring it up with everything going on in your life. It was just after I visited you in the hospital."

I frown at him as he gets in the driver's side. "Fuck that. You know you could've told me. I would've been here for you as much as I could." I don't comment on the bitter hurt that fills me knowing he didn't need my support anymore. Not like when we were kids. "Glad you won though."

He grabs my shoulder. "Yeah, I know. But I also kind of enjoyed you not seeing that side of me. Turns out I'm a bit of an asshole when it comes to getting my due diligence."

"You're always an asshole," I tell him sweetly. "Smells like a chick in here." Even my seatbelt has hints of perfume on it as I buckle in.

"Culero, I told you I'm seeing someone," Gonzales complains. He pops me on the back of the head.

I take a pointed sniff and look at him only to be met with an uncaring glance. Gonzales always made fun of me for blushing so easily. I've tried to make him blush at any opportunity I get.

"You tell her you love her yet?"

"You get your first kiss yet?" he shoots back.

He knows I have. In the basement of his mom's house during a middle school party where we pretended the Bojangles sweet tea was spiked. I told him it didn't count because I wasn't even dating the girl, and he's held it over my head ever since.

By middle school standards: I still have not, despite all the men I've kissed and slept with.

Gonzales laughs as soon as my cheeks flare up. Despite my embarrassment, it feels good to be here again with my best friend.

Sometimes, I wish Gonzales would have gone to Afghanistan with me. Then I remember Smith holding me down as Doc sawed my leg off to get me out from under the rubble, and I change my mind. Gonzales doesn't deserve any more pain in his life.

"How's my old man?" I ask once we hit the highway, hands clawing at the seatbelt constricting me—we're driving too fast to be on the lookout for IEDs.

Gonzales grunts an affirmative and goes on to tell me my dad gave him a B- in introduction to political science. The sound of Gonzales's complaints does nothing to deter my swiveling head. Since he's not looking for IEDs, I'm forced to.

Inu barks from the back seat and I subconsciously flip the watch on my wrist over, confused. The numbers are too high, but this isn't the time to worry over it. Inu barks again, giving away our position and I naturally brace for the onslaught of bullets as I reach for my gun.

Instead of my gun strapped to my chest, the desperate flailing of my body comes into contact with Inu's wet tongue. I try to push her off but she's insistent, trying to climb over the back of the Humvee.

"I'm pulling over," Smith says from beside me.

He flips on his blinker and turns down the music that had already been playing in the background, a heavy metal song Smith loves to play on repeat. Without the noise, I begin to realize there's something off about the Humvee. About Smith. Inu being here. Me.

As soon as the hazards flick on, Inu is finally able to gain a grip on the car and jumps into my lap, her wet tongue hot and humid against my face.

"Isamu, would you like the med bag?" Gonzales asks, voice steady and even.

I fight for air against Inu's incessant care and rip open the door, throwing my legs over the side of the Mustang and inhaling humid air as deeply as I can. Gonzales's hand is tight against the back of my shirt, and I try to bat him away weakly.

"It's fine," I tell him through a gasp. "I'm good. I figured it out."

But he doesn't let go until a precariously balanced Inu starts kneading against my legs, like a cat making bread.

We don't speak as I listen to the cars drive by, trying to haul my brain back from the desert. My fingers itch for cigarettes I don't smoke anymore, and I supplement it with running my hands through Inu's coarse fur. Her big brown eyes look up at me and I watch her wet nose flare as she smells me. She presses her nose into my chest and stops her kneading.

"Do you need anything?" Gonzales asks, hand warm where it rests on my lower back in silent support.

I'd had a similar incident in the cab ride with my mom as we headed back from the airport in Tokyo. She had laid my head on her lap and ran her fingers through my hair, repeating, "imagine all the cherry blossoms we'll see once we go to Kawazu." I imagined them then and try again now as Inu presses against my aggressively beating heart.

"Can you, uh, can you change the music? This is Smith's favorite song."

Cars are a little rough on my PTSD without the added bonus of the music I listened to while in Afghanistan.

Gonzales changes the song, finding a completely different genre as he puts on some pop hits. I'm forced to put in strength I don't feel to lift my prosthesis and Inu back into the car. My breathing is still shallow, cramped even further as we start driving again.

"You can hold my hand if you want," Gonzales says, voice light in joke even though his words hold concern.

"Suck my dick," I gasp out, craning over Inu to look over at him, taking his hand all the same. It's more for him than me since Inu already grounds me.

Gonzales and I immediately break out into sibling-like bickering that helps ease me into calmness more than anything else could right now. I missed this. I missed Gonzales's sharp humor and bear hugs. I missed his kind heart and easily given smiles.

"I missed you, fuckhead," I tell him in a break of our easily flowing trash talk.

He releases my hand to clasp my shoulder as we take the exit, making sure to mind both the dog still hugging my chest and the curves of the road.

"Missed you too, güey."

As we winddown the roads, the dark green giants encroach the car. They're preparing to fall and crush us under mother nature, not even a lick of blue sky visible between their branches. It feels like a fantasy world—with leaves too green to be anything but full of magic, and air rich with the smell of life. North Carolina is an envious landscape with these trees, making even most city slicking folks long for the countryside.

The trees finally expand and branch out as we approach my childhood home. On the farthest end in a suburban neighborhood, it seems to randomly erupt from the surrounding woods.

When I was little, the trees behind our house served as a jungle gym for Gonzales and I. We'd pretend we were on the back of woodland giants as we climbed them, or dive and roll between their trunks like ninjas—stealing their branches and swinging them around like the katanas in my dad's bedtime stories.

As we grew up, we invited our friends from the basketball team as we ran through the trees playing tag, until someone finally thwacked themselves on a branch so hard that he split his forehead open.

We barely visited the woods in high school, instead spending all our time at the basketball court or the gym. The only time I really went back was when Gonzales appeared outside my door in the middle of the night, eyes black and blue, limping visibly as he dumped his and his sister's bags on the floor.

He bowed low to my concerned old man, a sign of respect in our household, and asked if they could both stay with us. That night, Gonzales and I sat out in the woods smoking our first joint as he threw rocks—and eventually punches—at trees.

Gonzales stayed with us even after his sister went back home, mentioning something about apologies and shiny gifts from their mother. All bought with a credit card taken out in Gonzales's name.

At the end of Duke's school year, all those memories will belong to someone else. I hate that my dad is selling our house.

I peek over at Gonzales and watch his eyes trace the memories in those trees.

"When's the last time you came home?" I ask him.

"Last Sunday. Your old man puts up your Ramses stuffie in your seat."

I groan, imagining my ram stuffed animal sitting at the dining table. "He does not." I'm sure he does because even if I was never smart enough to go to the Duke, he supported my lifetime obsession with its biggest rival: UNC. Well, he hoped I'd go to school there, but I knew from the start that college wasn't for me.

Ignoring Gonzales's laughter behind me, I ease the car door open. Inu drops to the grass gracefully, more like a gazelle than a rottweiler, and picks up her foot in offense at the damp grass.

"You don't need me to hold your leash now, right?" I ask Inu.

She shakes her head—more a complaint about the moisture than in response—before I tell her, "Get busy," the general command to let her know she's free to piss at her leisure.

The door to my parents' house swings open, revealing my dad in his typical house slippers and an apron—a survival tool he picked up after my mom was forced to bail on us in order to care for her ailing mother back in Japan.

"You tell me I can't pick you up from the airport but once you're finally here, you don't even come in and let me say hi to my granddaughter?" His arms flap around in tune with his flailing hair leaving numerous strands sticking out left and right. He's clearly been pulling at it as he tries to gather his bearings in the kitchen. It's good to see him making the effort.

I look at Inu where she's crouching and taking a shit in my dad's beautiful green lawn; better than the intricate Japanese Garden he keeps in the backyard. "Inu had to pee," responding to my dad in Japanese, just for the opportunity to call her dog.

My dad frowns at the name and looks down, and I realize he isn't looking at her as his frown deepens. I wore shorts today because it's the easiest way to go through airport security. He's seen my prosthesis before, but I know it still makes him sad.

He turns and clomps back into the house, where I can already smell bamboo and the sea as food cooks, and I give him the space he needs to get his emotions back in order.

"Are you really going to leave? Now that you're finally back, I mean," Gonzales asks.

"Yeah man." What's the point in staying if no one will be left, goes unsaid.

The army was my ticket to citizenship. Early retirement and a lifetime paycheck are just added bonuses. The idea of seeing the world has always been more appealing to me than sitting behind a desk at some nine-to-five. Now, I just don't have anywhere to come home to when I need it. My dad will be in Japan and who knows where Gonzales will be.

Gonzales follows my dad inside, taking off his shoes at the door and sliding on his own slippers, comfortable in a house that's as much his as it is mine.

I feel some semblance of relief after my welcome, even though I have to crouch on my swollen thigh to pick up Inu's crap. The discomfort from the car is slowly dragged out of me like a rusty knife being pulled from my gut.

All of my boxes are piled in my dad's living room when I walk in. There are blind spots all over, the forest looming beyond my dad's expansive garden, hiding men holding guns. The knife digs deeper.

I stiffly maneuver around the boxes to the kitchen, grabbing an icepack from the fridge while I dodge my dad and Gonzales cooking dinner. My dad intercepts me as I walk past him a second time and pulls me down to kiss the top of my head. He says something that sounds distant and buzzy to my tinnitus affected ears.

I pat his back, wishing for a better reunion but too fixated on the pain in my thigh and the fears in my head.

Returning to the living room, I haul my med bag and backpack over to the couch before plopping down.

"Inu, closer," I call.

She approaches from where she's been hesitantly watching me, waiting for commands, and I unclip her own medical bag before undoing her support harness.

"Release."

Before I can even offer her a treat for a job well done, she takes off. Her teeth flash as she sprints through the house so excitedly that her back bunches up and her tail whips back and forth to assist her sharp turns. She zooms around the boxes until, tuckered out, she ventures back to me.

She shakes out her fur and I stroke her back as I pull a treat from my pocket to feed her.

"You were such a good girl," I coo quietly as she leans into my scratches, tongue lolling out in satisfaction from her spent energy.

I know she's a service animal, but I've always wanted a dog. This isn't necessarily how I imagined it happening, but the joy is still there. There's a calming presence from having her so nearby. It was once that moments alone quickly turned to fear and terror, nothing but my thoughts to keep me company. Mood swings caused by my PTSD make me bitter, angry, depressed, apathetic. I feared that who I was becoming was a husk of the man that I once was.

But now when I wake with a shout, hands clutching a limb no longer present, it's Inu's wet nose I see; tongue lapping at the tears shed in my sleep. Bitterness has transformed into coarse fur between my fingers; anger, the wagging of a tail; depression, a walk through a sun-soaked park; apathy, a caring mouth to feed and love.

Inu has rekindled my hope that this journey is far from over.

I pet her head one last time and she flops to the ground, huffing out an exhausted breath. It's been a big day for both of us. Tomorrow will be more tiring.

Shifting my prosthesis, minding that I don't hit my poorly deposited backpack or dog harness, I begin the process of taking it off. My residual limb is achy and my nerve endings are firing with pain from the altitude change of flying. I pull my socket until the suction releases, laying it on the ground next to me. Rolling off my silicone liner, my scar-ridden skin is exposed beneath, but I feel nothing but relief as everything in my body suddenly unwinds. Like taking off a tie or a bra after a long day but more intense.

The TV remote is just out of arm's reach—delaying the next best part of my relaxation routine—and I stare at it with longing before hauling myself up and using my single leg to hop over to it.

The highlights of the Panther's game fill the house, accompanying the sounds of my torn-apart family and their torn-apart cooking. Inu quietly snores below me as I massage pain cream into my residual limb. The Panthers are trash this year, and I groan as another pass is intercepted. The TV continues playing as the cream dries and I put on my compression shrink—something I only use on days that cause exceptional swelling. Traveling really is the worst.

Grabbing some decorative pillows, I prop up my leg before adjusting the still cold icepack to ease the swelling. I finally feel the first relaxing breath enter my lungs, chasing away the serrated knife with distraction and peace, and I let myself fall into it as I cart my fingers through Inu's fur.

Fullepub

Fullepub