Chapter 8

8

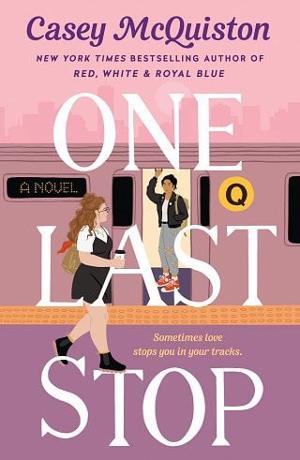

new york > brooklyn > community > missed connections

Posted June 8, 1999

Girl with leather jacket on Q train at 14th Street-Union Square (Manhattan)

Dear Beautiful Stranger, you’ll probably never see this, but I had to try. I only saw you for about thirty seconds, but I can’t forget them. I was standing on the platform waiting for the Q on Friday morning when it pulled up and you were standing there. You looked at me, and I looked at you. You smiled, and I smiled. Then the doors closed. I was so busy looking at you, I forgot to get on the train. I had to wait ten minutes for another one and was late for work. I was wearing a purple dress and platform Skechers. I think I’m in love with you.

Isaiah opens the door wearing a top hat, leather leggings, and a violently ugly button-down.

“You look like a member of Toto,” Wes says.

“And what better day than this holy Sunday to bless the rains down in Africa,” he says, waving them into his apartment with a flourish.

The inside of Isaiah’s place feels like him: a sleek leather sectional, stuffed and meticulously organized bookshelves, splashes of color in rugs and paintings and a silk robe slung over the back of a kitchen chair. Tasteful, stylish, well-organized, with a spare bedroom full of drag tucked beside the kitchen. His polished walnut dining table is decorated with dozens of Jesus figurines dressed in homemade drag, and the faint sounds of the Jesus Christ Superstar soundtrack underscore the sloshing of the punch he’s making at the counter.

So this is the event announced via handwritten flyer shoved under their door: Isaiah’s annual drag family Easter brunch.

“Loving the sacrilege,” Niko says, unloading a pan of vegetarian pasteles. He picks up one of the figurines, which is wrapped in a bedazzled sock. “White Jesus looks great in puce.”

August hauls her contribution—an aluminum dish full of Billy’s biscuits—over the threshold and contemplates if she’s the reason these two households are finally merging. It’s technically the first time the gang has been invited to the brunch, unless you count last year when the party spilled into the hall and Myla ended up getting a lap dance from a Bronx queen on her way to the mailbox. But last week, August rode the Popeyes service elevator with Isaiah and made a point to mention Wes’s sulking fit after his sister Instagrammed a Wes-less Passover seder.

“Are we the first ones?” August asks.

Isaiah shoots her a look over his shoulder. “You ever met a punctual drag queen? Why do you think we’re having brunch at seven o’clock at night?”

“Point,” she says. “Wes made scones.”

“It’s nothing special,” Wes grumbles as he shoulders past her to the kitchen.

“Tell him what kind.”

There’s a heavy pause in which she can practically hear Wes’s teeth grinding.

“Orange cardamom with a maple chai drizzle,” he bites out with all the fury in his tiny body.

“Oh shit, that’s what my sister’s bringing,” Isaiah says.

Wes looks stricken. “Really?”

“No, dumbass, she’s gonna show up with a bunch of Doritos and a ziplock bag of weed like she always does,” Isaiah says with a happy laugh, and Wes turns delightfully pink.

“Praise it and blaze it,” Myla comments, flopping onto the couch.

When the first members of Isaiah’s drag family start to show—Sara Tonin in dewy daytime drag and a handful of twenty-somethings with flashy manicures and thick-framed glasses to hide their shaved-off brows—the music cranks up and the lights crank down. August is quickly realizing that it’s only a brunch in the absolute loosest definition of the word: there is brunch food, yes, and Isaiah introduces her to a Montreal queen hot off a touring gig with a fistful of cash and a Nalgene full of mimosas. But, mostly, it’s a party.

Apartment 6F isn’t the the only group outside of Isaiah’s drag family to warrant an invitation. There’s the morning shift guy from the bodega, the owner of one of the jerk chicken joints, stoners from the park. There’s Isaiah’s sister, fresh off the train from Philly with purple box braids down to her waist and a Wawa bag over her shoulder. Every employee from the Popeyes downstairs ends up there the second they’ve clocked out, passing around boxes of spicy dark. August recognizes the guy who always lets them on the service elevator, still wearing a nametag that says GREGORY, half the letters rubbed off so it reads REG RY.

The party fills and fills, and August huddles in the kitchen between Isaiah and Wes, the former trying to greet every person who stumbles through the door while the latter pretends he’s not watching him do it.

“Wait, oh my God,” Isaiah says suddenly, goggling at the door. “Is that—Jade, Jade, is that Vera Harry? Oh my God, I’ve never seen her out of drag, you were right, bitch!” He turns to them, gesturing across the room at an incredibly hot and stubbly guy who’s walked in. He looks like he fell out of a CW show and into Isaiah’s living room. Wes is instantly glaring. “That is a new queen, moved from LA last month, everybody’s been talking about her. She’s this crazy stunt queen, but then, out of drag? Trade. Best thing to ever happen to Thursday nights.”

“Sucks for Thursday nights,” Wes mutters, but Isaiah has already vanished into the crowd.

“Oof,” August says, “you’re jealous.”

“Wow, holy shit, you figured it out. You’re gonna win a Peabody Award for reporting,” Wes deadpans. “Where’s the keg? I was told there would be a keg.”

Noisy minutes lurch by in a mess of shiny eyelids and Isaiah’s curated playlist—it’s just shifted from “Your Own Personal Jesus” to “Faith” by George Michael—and August is snatching a biscuit from the tray she brought when someone sets a platter of bun-and-cheese down beside it and says, “Shit, I almost brought the same thing. That would have been awkward.”

August looks up, and there’s Winfield in a silk shirt covered in cartoon fish, his braids bundled up on top of his head. Beside him is Lucie who, when she’s not in her Billy’s uniform, apparently favors extremely tiny black dresses and lace-up boots. She looks more like a girl in an assassin movie than the manager of a pancake joint. August stares.

“You— What are you doing here? Y’all know Isaiah?”

“I know Annie,” Winfield says. “She didn’t put me in drag my first time, but she sat at my counter enough to convince me I should try it.”

What?

“You’re—you do drag? But you’ve never mentioned—and you’re not—” August fumbles with half a dozen ways to end that sentence before landing eloquently on, “You have a beard?”

“What, you never met a bearded pansexual drag queen?” He laughs, and it’s then that August notices: Winfield and Lucie are holding hands. What in the world goes on at drag family Easter brunch?

“I—you—y’all are—?”

“Mm-hmm,” Winfield hums happily.

“As fun as it is to break your brain,” Lucie says, “nobody at work knows. Tell them and I break your arm.”

“Oh my God. Okay. You’re…” August’s head is going to explode. She looks at Winfield and gasps, “Oh fuck, that’s why you know so much Czech.”

Winfield laughs, and they disappear as quickly as they appeared, and it is … nice, August thinks. The two of them together. Like Isaiah and Wes or Myla and Niko, it makes a strange sense. And Lucie—she looked happy, affectionate even, which is incredible, since August kind of assumed she was made from what they use at Billy’s to scrub out the floor drains. Emotional steel wool.

By the punch bowl, the conversation has shifted to everyone’s Easter family traditions. August refills her cup as Isaiah asks Myla, “What about you?”

“My parents are, like, hippie agnostics, so we never celebrated. I’m pretty sure that’s the only thing Niko’s parents don’t like about me, my heathen upbringing,” she says, rolling her eyes as Niko laughs and throws an arm over her shoulders. “Our big April holiday growing up was Tomb Sweeping Day, but my grandparents and great-grandparents keep refusing to die, so we just burn a paper Ferrari every year for my great-uncle who was in love with his car.”

“My parents always made us go to Sábado de Gloria,” Niko chimes in. “The Catholic church taught me everything I know about drama. And candles.”

“Oh, no shit?” Isaiah says appreciatively. “My pops is a pastor. Mom leads the choir. Our parents should get together with the blood of Christ sometime. Except mine are Methodist, so it’s grape juice.”

Wes, who is perched on the countertop observing the conversation with the vaguest of interest, says, “August, didn’t you go to Catholic school for a million years? Is your family horny for Jesus too?”

“Only the extended family,” she says. “Didn’t go for Jesus reasons. Louisiana public schools are crazy underfunded and my mom wanted me to go private, so I went and we were broke my whole life. Super great time. One of the nuns got fired for selling cocaine to students.”

“Damn,” Wes says. He never did find the keg, but there’s a thirty-rack of PBR beside him, and he’s fishing one out. “Wanna shotgun a beer?”

“I absolutely don’t,” August says, and takes the beer Wes holds out anyway. She untucks her pocketknife from her jean jacket and hands it over, then follows Wes’s lead and jams it into the side of her can.

“I still think that knife is cool,” Wes says, and they pop the tops and chug.

When people start having to do shots in the hallway, Myla flings open the door to 6F and yells, “Shoes off and nobody touch the plants!” And everything overflows into both apartments, drag queens perched on the steamer trunk, Popeyes aprons dropped in the hall, Wes reclined across Isaiah’s kitchen table like a Renaissance painting, Vera Harry cradling Noodles in his beefy arms. Myla busts out the grocery bag of Lunar New Year candy her mom sent and starts passing it around the room. Isaiah’s Canadian friend tromps by with a box of wine on her shoulder, singing “moooore Fraaanziaaaa” to the tune of “O Canada.”

At some point, August realizes her phone’s been chiming insistently from her pocket. When she pulls it out, all the messages have collected to fill the screen. She swallows down an embarrassingly pleased sound and tries to play it off as a burp.

“Who’s blowing up your phone, Baby Smurf?” Myla says, as if she doesn’t know. August tilts her phone so Myla can see, bearing her weight when she leans in so close that August can smell the orangey lotion she puts on after showers.

Hello, I’m very bored.—Jane

Hi August!—Jane

Are you getting these?—Jane

Hellooooo?—Jane Su, Q Train, Brooklyn, NY

“Aw, she’s already learned how to double text,” Myla says. “Does she think she has to sign it like a letter?”

“I guess I left that part out when I was showing her how to use her phone.”

“It’s so cute,” Myla says. “You’re so cute.”

“I’m not cute,” August says, frowning. “I’m—I’m tough. Like a cactus.”

“Oh, August,” Myla says. Her voice is so loud. She’s very drunk. August is very drunk, she realizes, because she keeps looking at Myla and thinking how cool her eyeshadow is and how pretty she is and how nuts it is that she even wants to be August’s friend. Myla grabs her chin in one hand, squeezing until her lips poke out like a fish. “You’re a cream puff. You’re a cupcake. You’re a yarn ball. You’re—you’re a little sugar pumpkin.”

“I’m a garlic clove,” August says. “Pungent. Fifty layers.”

“And the best part of every dish.”

“Gross.”

“We should call her.”

“What?”

“Yeah, come on, let’s call her!”

How it happens is a blur—August doesn’t know if she agrees, or why, but her phone is in her hand and a call connecting, and—

“August?”

“Jane?”

“Did you call me from a concert?” Jane shouts over the sound of Patti LaBelle wailing “New Attitude” on someone’s Bluetooth speaker. “Where are you?”

“Easter brunch!” August yells back.

“Look, I know I don’t have the firmest grasp on time, but I’m pretty sure it’s really late for brunch.”

“What, are you into rules now?”

“Hell no,” Jane says, instantly affronted. “If you care what time brunch happens, you’re a cop.”

That’s something she’s picked up from Myla, who August eventually allowed to visit Jane again, and who loves to say that all kinds of things—paying rent on time, ordering a cinnamon raisin bagel—make you a cop. August smiles at the idea of her friends rubbing off on Jane, at having friends, at having someone for her friends to rub off on. She wants Jane to be there so badly that she tucks her phone into the pocket by her heart and starts carrying Jane around the party.

It’s one of those nights. Not that August has experienced a night like this—not firsthand, at least. She’s been to parties, but she’s not much of a drinker or a smoker, even less of a dazzling conversationalist. She’s mostly observed them like some kind of house party anthropologist, never understanding how people could fall in and out of connections and conversations, flipping switches of moods and patterns of speech so easily.

But she finds herself embroiled in a mostly Spanish debate about grilled cheese sandwiches between Niko and the bodega guy (“Once you put any protein other than bacon on there, that shit is officially a melt,” Jane weighs in from her pocket) and a mostly lawless drinking game in the next (“Never have I ever thrown a molotov cocktail,” Jane says. “Didn’t you hear the rules? When you say it like that, you’re saying that you have,” August says. “Yeah,” Jane agrees, “I know.”). For once, she’s not thinking about staying alert to fend off danger. It’s all people Isaiah knows and trusts, and August knows and trusts Isaiah.

And she’s got Jane with her, which she fucking loves. It makes everything easier, makes her braver. A Jane in her pocket. Pocket Jane.

She finds herself wedged between Lucie and Winfield, shouting over the music about customers at Billy’s. Then she’s trading jokes with Vera Harry, and she’s laughing so hard she spills her drink down her chin, and Isaiah’s sister calls out, “Not saying shit’s gone off the rails, but I just saw someone mix schnapps with a Capri Sun and someone else is in the bathtub handing out shrooms.”

And then somehow, she’s next to Niko, as he goes on and on about the existential dread of being a young person under climate change, twirling the thread of the conversation around his finger like a magician. It hits her like things do sometimes when you’re buzzed enough to forget the context your brain has built to understand something: Niko is a psychic. She’s friends with a whole psychic, and she believes him.

“Can I ask you a personal question?” August says to him once the group dissolves, hearing her voice come out sloppy.

“Should I go?” Jane says from her pocket.

“Noooo,” August says to her phone.

Niko eyes her over his drink. “Ask away.”

“When did you know?”

“That I was trans?”

August blinks at him. “No. That you were a psychic.”

“Oh,” Niko says. He shakes his head, the fang dangling from his ear swinging. “Whenever someone asks me personal questions, it’s always about being trans. That’s, like, so low on the list of the most interesting things about me. But it’s funny because the answer’s the same. I just always knew.”

“Really?” August thinks distantly about her gradual stumble into knowing she was bisexual, the years of confusing crushes she tried to rationalize away. She can’t imagine always knowing something huge about herself and never questioning it.

“Yeah. I knew I was a boy and I knew my sister was a girl and I knew that the people who lived in our house before us had gotten a divorce because the wife was having an affair, and that was it,” he explains. “I don’t even remember coming out to my parents or telling them I could see things they couldn’t. It was just always … what it was.”

“And your family, they’re—?”

“Catholic?” Niko says. “Yeah, they are. Kinda. More when I was a kid. The whole psychic thing—my mom always called it my gift from God. So they believed me about being a boy. Our church wasn’t so chill about it when I wanted to transition though. My mom kinda got into it with the priest, so none of the Riveras have been to mass in a while. Not that my abuelo knows that.”

“That’s cool,” Jane’s voice says.

“Very cool,” August agrees. Suddenly she knows where Niko gets his confidence from. She pulls on his arm. “Come on.”

“Where?”

“You have to be on my team for Rolly Bangs.”

The battered office chair appears out of nowhere, and Wes tapes off the floor of the hallway while Myla stands on a table and shouts the rules. An assortment of protective gear manifests on the kitchen counter: two bicycle helmets, Myla’s welding goggles, some ski gear that must belong to Wes, one lonely kneepad. August posts a sheet of paper on the wall and gets Isaiah to help her devise a tournament bracket—two drunk brains make one smart brain—and it’s on, the kitchen cleared and cheering crowds gathered on either side of the apartment as the games start.

August puts on a helmet, and when Niko flings her chair toward the hallway and she goes flying and screaming through the air, Jane warm in her pocket and no care for whether she breaks something, the only thought in her head is that she’s twenty-three years old. She’s twenty-three years old, and she’s doing something absolutely stupid, and she’s allowed to do absolutely stupid things whenever she wants, and the rest doesn’t have to matter right now. How had she not realized it sooner?

As it turns out, letting herself have fun is fun.

“Where does that disembodied voice keep coming from?” says Isaiah between rounds, sidling up beside August. He’s wearing a fur muff as a helmet.

“That’s August’s girlfriend,” Wes supplies, slurring slightly. “She’s a ghost.”

“Oh my God, I knew this place was haunted,” Isaiah says. “Wait, the one from the séance? She’s—?”

Someone else leans into the conversation. “Séance?”

“Ghost?” Sara Tonin chimes in from atop the refrigerator.

“Is she hot?” Isaiah’s sister asks.

“She’s not my girlfriend,” August says, waving them off. She points to the phone sticking out of her front pocket. “And she’s not a ghost, she’s just on speaker.”

“Boo,” says Jane’s voice.

“She’s always wearing the exact same thing,” Wes says as he hauls the office chair back, one of the wheels listing pathetically. “That’s ghost behavior if you ask me.”

“If I’m ever a ghost, I hope I get a choice in what I’m cursed to wear for the rest of eternity,” Isaiah says. “Like, do you think it’s just whatever you’re wearing when you die? Or is there an afterlife greatest hits mood board where you get to assemble your own ghost drag?”

“If I get to pick, I want to be wearing, like…” Myla thinks about it for a long second. Her drink sloshes down her arm. “One of those jumpsuits from the end of Mamma Mia. I go to haunt people but it always turns into a musical number. That’s the energy I want to bring to the hereafter.”

“Brocade suit, open jacket, no shirt,” Niko says confidently.

“Wes,” Myla shouts at him as he climbs into the rolling chair, “what would your ghost wear?”

He straps on a pair of ski goggles. “A slanket covered in shrimp chip crumbs.”

“Very Tiny Tim,” Isaiah notes.

“Shut up and throw me across the room, you big bitch.”

Isaiah obliges, and the tournament continues, but he comes back three rounds later, smiling a broad smile, the gap between his two front teeth unfairly charming.

He points at August’s phone. “What’s her name?”

“Jane,” August says.

“Jane,” Isaiah repeats, leaning into August’s boobs to shout at the phone. “Jane! Why aren’t you here at my party?”

“Because she’s a blip in reality from the 1970s bound to the Q and she can’t leave,” Niko supplies.

“What he said,” Jane agrees.

Isaiah ignores them and continues to yell at August’s tits. “Jane! The party’s not over yet! You should come!”

“Man, I’d love to,” Jane says, “I haven’t been to a good party in forever. And I’m pretty sure my birthday is coming up.”

“Your birthday?” Isaiah says. “You’re having a party for that, right? I wanna come.”

“Probably not,” Jane tells him. “I’m sort of—well, my friends are kind of unavailable.”

“That’s such bullshit. Oh my God. You can’t have a birthday and not celebrate it.” Isaiah leans back and addresses the party. “Hey! Hey everybody! Since this is my party, I get to decide what kind of party it is, and I am deciding it’s Jane’s birthday party!”

“I don’t know who Jane is, but okay!” someone yells.

“How soon can you get here, Jane?”

“I—”

And maybe Isaiah remembers the séance, and maybe he believes what’s happening here, and maybe he sees the panicked look August and Niko exchange, or maybe he’s just drunk. But his grin spreads impossibly wider, and he says, “Actually. Hang on. Everybody, please transfer your drink to an unmarked container, we’re taking it to the subway!”

Isaiah’s friends are nothing if not game—and, in many cases, crossed—so they flow down the stairs and out onto the street like a dam breaking, drinks in the air, caftans and capes and aprons trailing behind them. August is between Lucie and Sara Tonin, carried by the current toward her usual station.

“Which one is he?” Sara is asking Lucie.

Lucie points at Winfield, who’s throwing his head back to laugh, glitter glinting in his beard, looking like the life of the party. She tamps down a smile and says, “That’s him,” and August laughs and wants so badly to know what it feels like to show off the person who’s yours from across the crowd.

Then they all pile onto the train, August up front, pointing to Jane and telling Isaiah, “That’s her,” and she guesses she does know. Maybe what she really wants is to be the person across the crowd who belongs to someone.

“You brought me a party?” Jane asks as the car fills. Niko has already started blasting “Suavamente.”

“Technically, Isaiah brought you a party,” August points out.

But Jane looks around at the dozens of people on the train, painted nails and shrieks of laughter up and down her quiet night, and it’s August, not Isaiah, she looks at when she grins and says, “Thank you.”

Someone places a plastic crown on Jane’s head, and someone else presses a cup into her hand, and she rides on into the night, beaming and proud as a war hero.

Myla’s bag of candy starts making the rounds again—August can’t be sure, but she thinks someone has slipped in some edibles—and at some point, maybe after Isaiah and the Canadian Franzia enthusiast have a dance-off, August gets an idea. She convinces one of Isaiah’s drag daughters to give her the safety pin stuck through their earlobe, and she returns to Jane with it, grabbing her shoulders to catch her balance.

“Hi again,” Jane says, watching as August sticks the pin through the collar of her leather jacket. “What’s this?”

“Something we do in New Orleans,” August says, pulling a dollar out of her pocket and pinning it to Jane’s chest. “Thought you might remember.”

“Oh … oh yeah!” Jane says. “You pin a dollar to somebody’s shirt on their birthday, and when they go out—”

“—everyone who sees it is supposed to add a dollar,” August finishes, and the light of happy recognition in Jane’s eyes is so bright that August surprises herself with her own volume when she yells to the crowd. “Hey! Hey, new party rule! Pin the cash on the birthday girl! Keep it going, tell your friends!”

By the time the train loops back into Brooklyn, there are people swinging from subway poles and a stack of bills stuck through Jane’s safety pin, and August wants to do things she never wants to do. She wants to talk to people, shout through conversations. She wants to dance. She watches Wes as he slowly, warily lets himself slip against Isaiah’s side, and she turns to Jane and does the same. Niko bobs by with his Polaroid camera and snaps a photo of them, and August doesn’t even want to duck away.

Jane looks at her through a dusting of confetti that’s appeared out of nowhere and smiles, and August can’t control her body. She wants to climb up onto a seat, so she does.

“I like being taller than you,” she says to Jane, chewing on a piece of peanut and sesame brittle from Myla’s bag of candy.

“I don’t know,” Jane ribs her. “I don’t think it suits you.”

August swallows. She wants to do something stupid. She’s twenty-three years old, and she’s allowed to do something stupid. She touches the side of Jane’s neck and says, “Did you ever kiss any girls who were taller than you?”

Jane eyes her. “I don’t think so.”

“Too bad,” August says. She leans down so Jane has to tip her chin up to maintain eye contact, and she finds that she likes that angle quite a lot. “No memories to bring back.”

“Yeah,” Jane says. “It’d just be kissing to kiss.”

August is warm, and Jane is beautiful. Steady and improbable and unlike anyone August’s ever met in her life. “Sure would.”

“Uh-huh.” Jane covers August’s hand with hers, their fingers tangling. “And you’re drunk. I don’t think—”

“I’m not that drunk,” August says. “I’m happy.”

She sways forward, and she lets herself kiss Jane on the mouth.

For half a second, the train and the party and everything else exist on the other side of a pocket of air. They’re underground, underwater, sharing a breath. August brushes her thumb behind Jane’s ear, and Jane’s mouth parts, and—

Jane breaks off abruptly.

“What is that?” she asks.

August blinks at her. “Um. It was supposed to be a kiss.”

“No, that … the—your lips. They taste like peanuts. And … sesame paste? They taste like—”

She touches a hand to her mouth and staggers back, eyes wide, and August’s stomach drops. She’s remembering something. Someone. Another girl who’s not August.

“Oh,” Jane says finally. Someone crashes into her shoulder as they dance by, and she doesn’t even notice. “Oh, it’s—Biyu.”

“Who’s Biyu?”

Jane lowers her hand slowly and says, “I am.”

August’s feet hit the floor.

“I’m Biyu,” Jane goes on. August reaches out blindly and gets a handful of Jane’s jacket, watching her face, holding on to her as she trips backward into memories. “That’s my name—what my parents named me. Su Biyu. I was the oldest, and my sisters and me, we used to—we used to eat all the fah sung tong before the New Year party was even over, so my dad would hide them on top of the fridge in a sewing tin, but I always knew where it was, and he always knew when I stole some because he’d catch me smelling like—like peanuts.”

August tightens her grip. The music keeps playing. She thinks of storm surges, of rushes and walls of water, and holds on tighter, feels it coming and plants her feet.

“His name, Jane,” she says, suddenly and startlingly sober. “Tell me his name.”

“Biming,” she says. “My mom’s is Margaret. They own a—a restaurant. In Chinatown.”

“Here?”

“No—no. San Francisco. That’s where I’m from. We lived above the restaurant in a little apartment, and the wallpaper in the kitchen was green and gold, and my sisters and I shared a room and we—we had a cat. We had a cat and a pot of flowers by the front door and a picture of my po po next to the phone.”

“Okay,” August says. “What else do you remember?”

“I think…” A smile spreads across her face, awestruck and distant. “I think I remember everything.”

Fullepub

Fullepub