Chapter 4

4

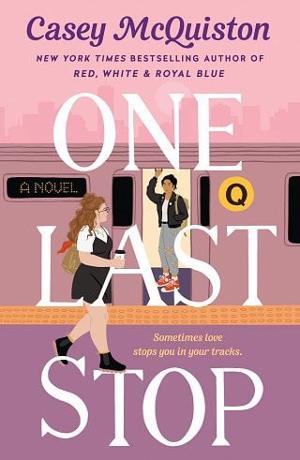

new york > brooklyn > community > missed connections

Posted November 3, 2007

Cute girl on Q train between Church Av & King’s Highway (Brooklyn)

Hi, if you’re reading this. We were both on the Q headed toward Manhattan. I was across from you. You were wearing a leather jacket and red hi-top Converse and listening to something on your headphones. I was wearing a red skirt and reading a paperback copy of Sputnik Sweetheart. Last night, November 2nd, around 8:30 p.m. You smiled at me, I dropped my book, and you laughed, but not in a mean way. I got off at King’s Highway. Please, please read this. I can’t stop thinking about you.

August can never take the Q again.

She can’t believe she asked Jane out. Jane. Jane of the effortless smiles and subway dance parties, who is probably a fucking poet or, like, a motorcycle mechanic. She probably went home that night and sat at a bar with her equally hot motorcycle poet friends and talked about how funny it was that this weird girl on her train asked her out, and then went to bed with her even hotter girlfriend and had nice, satisfying, un-clumsy sex with someone who isn’t a depressed twenty-three-year-old virgin. They’ll get up in the morning and make their cool and sexy sex-haver toast and drink their well-adjusted coffee and move on with their lives, and eventually, after enough weeks of August avoiding the Q, Jane will forget all about her.

August’s professor pulls up another PowerPoint slide, and August pulls up Google Maps and starts planning her new commute.

Great. Fine. She’ll never see Jane again. Or ask anyone out for the rest of her life. She was on a solid streak of belligerent solitude. She can pick it back up.

Cool.

Today’s lecture is on correlational research, and August is taking notes. She is. Measuring two variables to find the statistical relationship between them without any influence from other variables. Got it.

Like the correlation between August’s ability to focus on this lecture and the amount of athletic, mutually gratifying sex Jane is having with her hypothetical super hot and probably French girlfriend, like, right now. Not taking into consideration the extraneous variables of August’s empty stomach, her aching lower back from doubles at work, or her phone buzzing in her pocket as Myla and Wes argue in the group chat over tonight’s stir-fry. She’s pushed through those to take notes before. None were half as distracting as Jane.

It’s annoying, because Jane is just a person on a train. Simply a very beautiful woman with a nice-smelling leather jacket and a way of becoming the absolute shimmering focal point of every space she occupies. Only marginally the reason August hasn’t altered her commute once all semester.

It’s chill. August is, as she has been her entire life, very deeply chill.

She gives up and checks her phone.

august my lil bb i know you hate broc but we’re doing broc i’m sorry, Myla’s texted.

I don’t mind broccoli, August sends back.

I’m the one who hates broccoli, Wes sends with a pouty emoji.

ooo in that case i’m not sorry:), Myla replies.

This should be enough, she thinks. August has, however dubiously, stumbled into this tangle of people that want her to be a part of them. She’s lived for a long-ass time on less love than this. She’s been alone in every way. Now she’s only alone in some ways.

She texts back, Fun fact: broccoli is an excellent source of vitamin C. No scurvy for this bitch.

Within seconds, Myla has sent back AYYYYYYY and changed the name of the chat to SCURVY FLIRTY & THRIVING.

When August opens the door that night, Wes is sitting on the kitchen counter with an ice pack on his face, blood spattered down his chin.

“Jesus,” August says, dropping her bag next to Myla’s skateboard by the door, “what’d y’all do this time?”

“Rolly Bangs,” Wes says miserably. Myla is a few feet down the counter, chopping vegetables, while Niko dumps the remains of a planter into the trash. “They convinced me to do a round before I left for work, and now I have to call in on account of a busted lip and emotional distress because someone pushed the chair too hard.”

“You said you wanted to go for the record,” Myla says impartially.

“I could have lost a tooth,” Wes says.

Myla wipes her hands on her overalls and leans over. “You’re fine.”

“I’ve been maimed.”

“You knew the risks of the game.”

“It’s a game you came up with when you were fried off a pot cookie and Niko’s shady kombucha, not Game of fucking Thrones.”

“This is why you’re supposed to wait for the line judge to get home,” August says. “When y’all kill one another, I’m inheriting the apartment.”

Wes slumps off to the couch with a book, and Myla continues her work on dinner while Niko tends to the plants that weren’t casualties. August spreads her notes on research methods out on the living room floor and tries to catch up on what she missed in class.

“Anyway,” Myla is saying, telling Niko about work. “I told her I don’t care who her dead husband is, we don’t buy used jock straps, not even from members of the 1975 Super Bowl–winning Pittsburgh Steelers, because we sell nice things that aren’t covered in ball sweat.”

“More things are covered in ball sweat than you might imagine,” Niko says thoughtfully. “Ball sweat, actually, is all around us.”

“Okay, then, soaked in ball sweat,” Myla counters. “Brined like a Thanksgiving turkey in ball sweat. That was the situation we were dealing with.”

“Can we maybe not talk about ball sweat right before dinner?” August asks.

“Good point,” Myla concedes.

Niko looks up from a tomato plant at August, quizzical. “Hey, what’s up with you? Who hurt your feelings?”

Living with a psychic is a pain in the ass.

“It’s—ugh, it’s so stupid.”

Myla frowns. “Who do we need to frame for murder?”

“Nobody!” August says. “It’s—did you hear how the Q shut down for a few hours the other day? Well, I was on it, and there was this girl, and I thought we had, like, a moment.”

“Oh shit, really?” Myla says. She’s switched to peppers and is slicing them with a reckless enthusiasm that suggests she doesn’t care if a finger has to be reattached later. “Oh, that’s a Kate Winslet movie. Trapped in a survival scenario. Did you have to huddle naked for warmth? Are you bonded for life by trauma now?”

“It was like seventy degrees,” August says, “and no, actually, I thought we were having a moment, so I asked her out for a drink, and she turned me down, so I’m just gonna figure out a new commute and hopefully never see her again and forget this ever happened.”

“Turned you down, as in?” Myla asks.

“As in, she said no.”

“But in what way?” Niko asks.

“She said, ‘Sorry, but I can’t.’”

Myla tuts. “So, not that she’s not interested, but like … she can’t? That could mean anything.”

“Maybe she’s sober,” Niko suggests.

“Maybe she was busy,” Myla adds.

“Maybe she was on her way to dump her current girlfriend to be with you.”

“Maybe she’s, like, in some kind of complicated entanglement with an ex and she has to sort it out before she gets involved with someone.”

“Maybe she’s been cursed by a malevolent witch to never leave the subway, not even for dates with super cute girls who smell like lemons.”

“You told me that kind of thing can’t happen,” Wes says to Niko.

“Sure, no, it can’t,” Niko hedges.

“Thanks for noticing my lemon soap,” August mumbles.

“I bet your subway babe noticed it,” Myla says, waggling her eyebrows suggestively.

“Jesus,” August says. “No, there was definitely, like, a note of finality. It wasn’t ‘not right now.’ It was ‘not ever.’”

Myla sighs. “I don’t know. Maybe you wait and try again if you see her.”

It’s easy for Myla to say, with her perfectly highlighted cupid’s bow and self-satisfied confidence and hot boyfriend, but August has the sexual prowess of a goldfish and the emotional vocabulary to match. This was the second try. There’s no third.

“Babe, can you grab me those green onions out of the fridge?” Myla asks.

Niko, who has moved on to eyeballing his homemade Alcoholado collection with extreme scrutiny, says, “One second.”

“I got it,” August says, and she pulls herself up and pads over to the fridge.

The green onions are on an overcrowded shelf between a to-go box of pad thai and something Niko has been fermenting in a jar since August moved in. She hovers once she’s passed them off, examining the photos on the fridge door.

At the top: Myla with faded purple hair, orangey at ends, beaming in front of a mural. A blurry polaroid of Wes allowing Myla to smear cupcake icing down his nose. Niko, his hair a little longer, making faces at a display of radishes at an outdoor market.

Below, some older ones. A tiny Myla and her brother swaddled in towels next to a sign announcing the beach in Chinese, two parents draped in shawls and sunhats. And a photo of a child August can’t quite place: long hair topped with a pink bow, pouting in a Cinderella dress as Disney World glows in the background.

“Who’s this?” August asks.

Niko follows her finger and smiles softly. “Oh, that’s me.”

August looks at him, his sharp eyebrows and steady presence and slim cut jeans, and, well, she did wonder. She’s habitually observant, though she does try to never assume with things like this. But an aggressive kind of warmth rushes into her, and she smiles back. “Oh. Cool.”

That makes him laugh, hoarse and warm, and he pats August on the shoulder before wandering off to poke at the plant in the corner next to Judy. August swears that thing has grown a foot since she moved in. Sometimes she thinks it hums to itself at night.

It’s funny. That’s one big thing out of the way between the four of them, but it’s also a small thing. It makes a difference, but it also makes no difference at all.

Myla hands out bowls, and Wes shuts his book, and they sit on the floor around the steamer trunk and divvy up chopsticks and pass around a dish of rice.

Niko turns up the volume on House Hunters, which they’ve been hate-watching with the cable Myla stole from the apartment next door. The wife of this couple sells lactation cookies, the husband designs custom stained-glass windows, and they have a budget of $750,000 and a powerful need for an open-concept kitchen and a backyard for their child, Calliope.

“Why do rich people always have the worst possible taste?” Wes says, feeding a piece of broccoli to Noodles. “Those countertops are a hate crime.”

August snorts into her dinner, and Niko chooses that moment to whip the Polaroid camera off the bookshelf. He snaps a photo of August in an unflattering laugh, a baby corn halfway lodged in her windpipe.

“Goddammit, Niko!” she chokes out. He crows with laughter and strides off in his socks.

She hears the snap of a magnet—he’s added August to the fridge.

It doesn’t feel like a Friday that should change everything.

It’s the same as every Friday. Fight the shower for hot water (she’s finally getting the hang of it), cram cold leftovers into her mouth, make her way to campus. Return a book to the library. Sidestep a handsy stranger next to the falafel cart and trade tips for street meat. Hike back up the stairs because her name’s not Annie Depressant and she doesn’t have the nerve to ask about the service elevator inside Popeyes.

Change into her Pancake Billy’s T-shirt. Scrub at the circles under her eyes. Tuck her knife into her back pocket and make her way to work.

At least, she thinks, there will always be Billy’s. There’s Winfield, gently explaining the daily specials to a new hire who looks as scared shitless as August probably did on her first day. There’s Jerry, grumbling over the griddle, and Lucie, perched on a countertop, monitoring it all. Like the subway, Billy’s has been here for her every day, a constant at the center of her confusing New York universe—a dingy, grease-soaked little star.

Halfway into her shift, she sees it.

She’s ducking into the back hallway, checking her phone: a text from her mom, a dozen notifications in the household group chat, a reminder to refill her MetroCard. She stares at the wall, trying to remember if the MetroCard machine at her new station works, wishing she hadn’t had to change her whole commute—

And, oh.

There are hundreds of photos cluttering the walls of Billy’s, mismatched frames bumping together like bony shoulders. August has passed a lot of odd hours between rushes counting celebrities who’ve dined here, the vintage Dodgers photos wedged between Ray Liotta and Judith Light. But there’s this one photo, a foot to the left of the men’s room door, a sepia-toned four-by-six in a blue pearl frame. August must have looked past it a thousand times.

There’s a yellowed notecard stuck to it with four layers of tape, reinforced again and again over the years. In handwritten black ink: Pancake Billy’s House of Pancakes Grand Opening—June 7, 1976.

It’s Billy’s at its most pristine, not a scorched bit of Formica in sight, shot from above like the photographer climbed proudly up onto a barstool. There are customers with blown-out hair and shorts so short, their thighs must’ve stuck to the vinyl. On the left side of the frame, Jerry—no more than twenty-five—pouring a cup of coffee. August has to admit: he was a babe.

But what makes her rip the photo off the wall, frame and all, and fake a bout of puking so she can clock out early with it shoved down the front of her shirt—is the person in the bottom right corner.

The girl is leaning up against the corner of a booth, apron suggesting she wandered out of the kitchen to talk to some customers, the short sleeves of her T-shirt rolled up above the subtle curve of her biceps. Her hair’s chin-length and spiky, swept back from her face. A little longer than August is used to.

Below the cuff of her sleeve, an anchor tattoo. Above that, the tail feathers of a bird. At her elbow, the neat line of Chinese characters.

1976. Jane. A single dimple at one side of her mouth.

Barely a day younger than she looks every morning on the train.

August runs the twelve blocks home without stopping.

August’s first word was “case.”

It wasn’t a cute word for the baby book like “mama” (she called her mother Suzette as a toddler) or “dada” (never had one, just a sperm donor a week after her mom’s thirty-seventh birthday). It wasn’t something that would magically make her judgmental grandparents and their old New Orleans money decide they cared to speak to her mom or know August, like maybe “tax evasion” or “Huey P. Long.” It wasn’t even something cool.

No, it was simply the word she heard most while her mother taped episodes of Dateline and read crime novels out loud to her squishy baby form and worked the one great missing persons case of their lives.

Case.

She took developmental psych her sophomore year, so she knows crucial developmental phases. Age three, learning how to read, so she could hand her mom the file that starts with M instead of N. Age five, able to carry on a conversation independently, like explaining tearfully to the man at the front desk of a French Quarter apartment building how she’d gotten lost, so her mom could scavenge his files while he was distracted. It’s hardwired.

It’s too easy, now, to dig it all back out.

She’s sitting on her bedroom floor, photo on one side, notebook on the other filled with five front-and-back pages of notes and questions and half-formed theories like hot zombie? and marty mcfly??? Her bedspread is burritoed around her like a foil shock blanket on a plane crash survivor. She’s gone full True Detective. It’s been four hours.

She’s unearthed her mother’s LexisNexis password, filed three public records requests online, put holds on five different books at the library. She’s shaking down double-digit pages of Google search results, trying to find some kind of answer that isn’t completely batshit fucking insane. “Immortal hottie” has no relevant returns, only people in goth bands who look like Kylo Ren.

She’s taken the photo out of the frame, looked at it under natural light, LED light, yellow light, held it inches from her face, walked down to the pawn shop next to Niko’s work and bought a fucking magnifying glass to examine it. No evidence that it’s been doctored. Only the faded shape of Jane, tattoos and dimple and cocky set of her hips, the continuing, impossible fact that she’s there. Forty-five years ago, she’s there.

She said it, that day she told August her name. She worked at Billy’s.

She never mentioned when.

August paces her room, trying to make sense of what she knows. Jane worked at Pancake Billy’s when it opened in 1976, long enough for an off-menu item to be named after her. She’s intimately familiar with the workings of the Q, and presumably lives in either Brooklyn or Manhattan.

The scraps of Craigslist posts and articles and police reports and one 2015 People of the City Instagram post with Jane blurry in the background are all August has to go on. She’s searched every possible permutation of Jane Su she can think of, alternate spellings and romanizations—Sou, Soo, So, Soh. No luck.

But there’s something else, a pattern she’s starting to piece together, one she probably would have figured out if she weren’t always so determined to reason things away.

How Jane never had a heavier coat than her leather jacket, even when it was punishingly cold back in January. How she didn’t know who Joy Division was, the mess of her cassette collection, that she has a cassette player in the first place. It shouldn’t have been easy to always catch her train. They should have missed each other, just once. But they never have, not since the first week.

She … God. What if …

August pulls her laptop into her lap. Her hands hover indecisively over the keys.

Jane doesn’t age. She’s magnetic and charming and gorgeous. She … kind of lives underground.

The cursor on the Google search bar blinks expectantly. August blinks back.

Through a slight fog of hysteria, she remembers those weird dudes from Billy’s talking about the vampire community. She was pretty sure that was some kind of BDSM role-play thing. But what if—

August snaps her laptop shut.

Jesus Christ. What is she thinking? That Jane is some thousand-year-old succubus who’s really into punk music but can’t keep her references straight? That she spends her nights haunting the tunnels, eating rats and getting horned up over O-positive and using her supernatural charm to maneuver SPF 75 out of strangers’ Duane Reade bags? She’s Jane. She’s just Jane.

Really, sincerely, from the very bottom of August’s heart: What the fuck?

Somewhere beneath it all, a voice that sounds like August’s mom says she needs a primary source. An interview. Someone who can tell her exactly what she’s dealing with.

She thinks about Jerry, or even Billy, the owner of the restaurant. They must have known Jane. Jerry could tell her how long he’s been cooking the Su Special. If she shows them the picture, they might remember whether they ever caught her hissing at the jugs of minced garlic in the walk-in. But August’s job is hanging by a thin enough thread without barging into the kitchen demanding to know if any former employees displayed signs of bloodlust.

No, there’s someone else to talk to first.

Fullepub

Fullepub