Chapter 2

2

What’s Wrong with the Q?

By Andrew Gould and Natasha Brown

December 29, 2019

New Yorkers know better than to expect perfection or promptness from our subway system. But this week, there’s a new factor to the Q train’s spotty service: electrical surges have blown out lights, glitched announcement boards, and caused numerous stalled trains.

On Monday, the Manhattan Transit Authority alerted commuters to expect an hour delay on the Q train in both directions as they investigated the cause of the electrical malfunctions. Service resumed its normal schedule that afternoon, but reports of sudden stops have persisted.

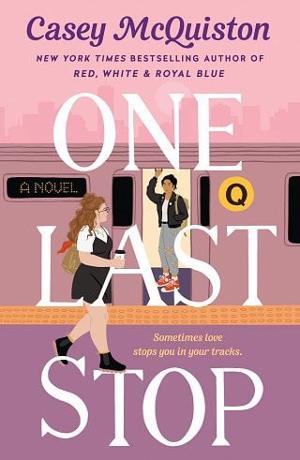

[Photo depicts commuters on a Brooklyn-bound Q train on the Manhattan Bridge. In the foreground is a mid-twenties Chinese American woman with short hair and a leather jacket, frowning up at a flickering light fixture.]

Brooklyn resident Jane Su takes the Q to Manhattan and back every day.

Tyler Martin for the New York Times

“I’ve decided to dunk Detective Primeaux’s balls in peanut butter and push him in the Pontchartrain,” August’s mom says. “Let the fish castrate him for me.”

“That’s a new one,” August notes, crouching behind a cart of dirty dishes, the only spot inside Billy’s where her phone gets more than one anemic bar. Her face is two inches from someone’s half-eaten Denver omelet. Life in New York is deeply glamorous. “What’d he do this time?”

“He told the receptionist to screen my calls.”

“They told you that?”

“I mean,” she says, “she didn’t have to. I can tell.”

August chews on the inside of her cheek. “Well. He’s a shit.”

“Yeah,” she agrees. August can hear her fussing with the five locks on her door as she gets home from work. “Anyway, how was your first day of class?”

“Same as always. A bunch of people who already know one another, and me, the extra in a college movie.”

“Well, they’re probably all shits.”

“Probably.”

August can picture her mom shrugging.

“Do you remember when you stole that tape of Say Anything from our neighbors?” she asks.

Despite herself, August laughs. “You were so mad at me.”

“And you made a copy. Seven years old, and you figured out how to pirate a movie. How many times did I catch you watching it in the middle of the night?”

“Like a million.”

“You were always crying your eyes out to that Peter Gabriel song. You got a soft heart, kid. I used to worry that’d get you hurt. But you surprised me. You grew out of it. You’re like me—you don’t need anyone. Remember that.”

“Yeah.” For half an embarrassing second, August’s mind flits back to the subway and the girl with the leather jacket. She swallows. “Yeah, you’re right. It’ll be fine.”

She pulls her phone away from her face to check the time. Shit. Break’s almost over.

She’s lucky she got the job at all, but not lucky enough to be good at it. She was maybe too convincing when Lucie the manager called her fake reference number and got August’s burner phone. The result: straight onto the floor, no training, picking things up as she goes.

“Side of bacon?” the guy at table nineteen asks August when she drops off his plate. He’s one of the regulars Winfield pointed out on her first day—a retired firefighter who’s come in for breakfast every day for the last twenty years. At least he likes Billy’s enough not to care about terrible service.

“Shit, I’m sorry.” August cringes. “Sorry for saying ‘shit.’”

“Forgot this,” says a voice behind her, thick with a Czech accent. Lucie swoops in with a side of bacon out of nowhere and snatches August by the arm toward the kitchen.

“Thank you,” August says, wincing at the nails digging into her elbow. “How’d you know?”

“I know everything,” Lucie says, bright red ponytail bobbing under the grimy lights. She releases August at the bar and returns to her fried egg sandwich and a draft of next week’s schedule. “You should remember that.”

“Sorry,” August says. “You’re a lifesaver. My pork product savior.”

Lucie pulls a face that makes her look like a bird of prey in liquid eyeliner. “You like jokes. I don’t.”

“Sorry.”

“Don’t like apologies either.”

August bites down another sorry and turns back to the register, trying to remember how to put in a rush order. She definitely forgot the side of hashbrowns for table seventeen and—

“Jerry!” Lucie shouts through the kitchen window. “Side of hashbrowns, on the fly!”

“Fuck you, Lucie!”

She yells something back in Czech.

“You know I don’t know what that means!”

“Behind,” Winfield warns as he brushes past with a full stack in each hand, blueberry on the left, butter pecan on the right. He inclines his head toward the kitchen, braids swinging, and says, “She called you an ugly cock, Jerry.”

Jerry, the world’s oldest fry cook, bellows out a laugh and throws some hashbrowns on the grill. Lucie, August has discovered, has superhuman eyesight and a habit of checking her employees’ work at the register from across the bar. It’d be annoying, except she’s saved August’s ass twice in five minutes.

“You are always forgetting,” she says, clicking her acrylics against her clipboard. “You eat?”

August thinks back over the last six hours of her shift. Did she spill half a plate of pancakes on herself? Yes. Did she eat any? “Uh … no.”

“That’s why you forget. You don’t eat.” She frowns at August like a disappointed mother, even though she can’t be older than twenty-nine.

“Jerry!” Lucie yells.

“What!”

“Su Special!”

“I already made you one!”

“For August!”

“Who?”

“New girl!”

“Ah,” he says, and he cracks two eggs onto the grill. “Fine.”

August twists the edge of her apron between her fingers, biting back a thank you before Lucie throttles her. “What’s a Su Special?”

“Trust me,” Lucie says impatiently. “Can you work a double Friday?”

The Su Special, it turns out, is an off-menu item—bacon, maple syrup, hot sauce, and a runny fried egg sandwiched between two pieces of Texas toast. And maybe it’s Jerry, his walrus mustache suggesting unknowable wisdom and his Brooklyn accent confirming seven decades of setting his internal clock by the light at Atlantic and Fourth, or Lucie, the first person at this job to remember August’s name and care if she’s living or dying, or because Billy’s is magic—but it’s the best sandwich August has ever eaten.

It’s nearly one in the morning when August clocks out and heads home, streets teeming and alive in muddy orange-brown. She trades a crumpled dollar from her tips for an orange at the bodega on the corner—she’s pretty sure she’s on a collision course with scurvy these days.

She digs her nail into the rind and starts peeling as her brain helpfully supplies the data: adult humans need sixty-five to ninety milligrams of vitamin C a day. One orange contains fifty-one. Not quite staving off the scurvy, but a start.

She thinks about this morning’s lecture and trying to find a cheap writing desk, about what Lucie’s story must be. About the cute girl from the Q train yesterday. Again. August is wearing the red scarf tonight, bundled warm and soft like a promise around her neck.

It’s not that she’s thought a lot about Subway Girl; it’s just that she’d work five doubles in a row if it meant she got to see Subway Girl again.

She’s passing through the pink glow of a neon sign when she realizes where she is—on Flatbush, across from the check-cashing place. This is where Niko said his psychic shop is.

It’s sandwiched between a pawn shop and a hair salon, peeling letters on the door that say MISS IVY. Niko says the owner is a chain-smoking, menopausal Argentinian woman named Ivy. The shop isn’t much, just a scuffed-up, grease-stained, gray industrial door attached to a nondescript storefront, the type you’d use for a Law & Order shooting location. The only hint to what’s inside is the single window bearing a neon PSYCHIC READINGS sign surrounded by hanging bundles of herbs and some—oh—those are teeth.

August has hated places like this as long as she can remember.

Well, almost.

There was one time, back in the days of bootleg Say Anything. August tugged her mom into a tiny psychic shop in the Quarter, one with shawls over every lamp so light spilled across the room like twilight. She remembers laying her hand-me-down pocketknife down between the candles, watching in awe as the person across the table read her mother’s cards. She went to Catholic school for most of her life, but that was the first and last time she really believed in something.

“You’ve lost someone very important to you,” the psychic said to her mother, but that’s easy to tell. Then they said he was dead, and Suzette Landry decided they weren’t seeing any more psychics in the city, because psychics were full of shit. And then the storm came, and for a long time, there were no psychics in the city to see.

So August stopped believing. Stuck to hard evidence. The only skeptic in a city full of ghosts. It suited her fine.

She shakes her head and pulls away, rounding the corner into the home stretch. Orange: done. Scurvy: at bay, for now.

On flight three of her building, she’s thinking it’s ironic—almost poetic—that she lives with a psychic. A quote-unquote psychic. A particularly observant guy with confident, strange charm and a suspicious number of candles. She wonders what Myla thinks, if she believes. Based on her Netflix watchlist and her collection of Dune merch, Myla’s a huge sci-fi nerd. Maybe she’s into it.

It’s not until she reaches into her purse at the door that she realizes her keys aren’t there.

“Shit.”

She attempts a knock—nothing. She could text to see if anyone’s awake … if her phone hadn’t died before her shift ended.

Guess she’s doing this, then.

She grabs her knife, flicks the blade out, and squares up, wedging it into the lock. She hasn’t done this since she was fifteen and locked out of the apartment because her mom lost track of time at the library again, but some shit you don’t forget. Tongue tucked between her teeth, she jiggles the knife until the lock clicks and gives.

Someone’s home after all, puttering around the hallway with earbuds in and a toolbag at their feet. There’s a bundle of sage burning on the kitchen counter. August hangs up her jacket and apron by the door and considers putting it out—they’ve already had one fire this week—when the person in the hall looks up and lets out a small yelp.

“Oh,” August says as the guy pulls an earbud out. He’s definitely not Niko or Myla, so—“You must be Wes. I’m August. I, uh, live here now?”

Wes is short and compact, a skinny, swarthy guy with bony wrists and ankles sticking out of gray sweats and a gigantic flannel cuffed five times. His features are strangely angelic despite the scowl they relax into. Like August, he’s got glasses perched on his nose, and he’s squinting at her through them.

“Hi,” he says.

“Good to finally meet you,” she tells him. He looks like he wants to bolt. Relatable.

“Yeah.”

“Night off?”

“Uh-huh.”

August has never met someone worse at first impressions than her, until now.

“Okay, well,” August says. “I’m going to bed.” She glances at the herbs smoldering on the counter. “Should I put that out?”

Wes returns to what he was doing—fiddling with the hinge on August’s bedroom door, apparently. “I had my ex over. Niko said the place was full of ‘frat energy.’ It’ll go out on its own. Niko’s stuff always does.”

“Of course,” she says. “Um, what are you … doing?”

He doesn’t say anything, just turns the knob and wiggles the door. Silence. It was creaky when August moved in. He fixed the hinge for her.

Wes scoops Noodles up in one arm and his toolbag in the other and vanishes down the hall.

“Thanks,” August calls after him. His shoulders scrunch up to his ears, as if nothing could displease him more than being thanked for an act of kindness.

“Cool knife,” he grunts as he shuts his bedroom door behind him.

Friday morning finds August shivering, one hand in the shower, begging it to warm up. It’s twenty-eight degrees outside. If she has to get in a cold shower, her soul will vacate the premises.

She checks her phone—twenty-five minutes before she has to be on the platform to catch her train for class. No time to reply to her mom’s texts about annoying library coworkers. She punches out some sympathetic emojis instead.

What did Myla say? Twenty minutes to get the hot water going, but ten if you’re nice? It’s been twelve.

“Please,” August says to the shower. “I am very cold and very tired, and I smell like the mayor of Hashbrown Town.”

The shower appears unmoved. Fuck it. She shuts off the faucet and resigns herself to another all-day aromatic experience.

Out in the hallway, Myla and Wes are on their hands and knees, sticking lines of masking tape down on the floor.

“Do I even want to ask?” August says as she steps over them.

“It’s for Rolly Bangs,” Myla calls over her shoulder.

August pulls on a sweater and sticks her head back out of her door. “Do you realize you just say words in any random order like they’re supposed to mean something?”

“Pointing this out has never stopped her,” says Wes, who looks and sounds like he stumbled in from a night shift. August wonders what Myla bribed him with to get his help before he retreated to his cave. “Rolly Bangs is a game we invented.”

“You start by the door in a rolling chair, and someone pushes you down the incline of the kitchen floor,” Myla explains. Of course she’s figured out a way to use a building code violation for entertainment. “That’s the Rolly part.”

“I’m scared to find out what the Bangs are,” August says.

“The Bang is when you hit that threshold right there,” Wes says. He points to the wooden lip where the hallway meets the kitchen. “Basically catapults you out of the chair.”

“The lines,” Myla says, ripping off the last piece of tape, “are to measure how far you fly before you hit the floor.”

August steps over them again, heading toward the door. Noodles circles her ankles, snuffling excitedly. “I can’t decide if I’m impressed or horrified.”

“My favorite emotional place,” Myla says. “That’s where horny lives.”

“I’m going to bed.” Wes throws his tape at Myla. “Good night.”

“Good morning.”

August is shrugging into her backpack when Myla meets her at the door with Noodles’s leash.

“Which way you walking?” she asks as Noodles flops around, tongue and ears flapping. He’s so cute, August can’t even be mad that she was definitely misled about how much this dog is going to be a part of her life.

“Parkside Avenue.”

“Ooh, I’m taking him to the park. Mind if I walk with you?”

The thing about Myla, August is learning, is that she doesn’t plant a seed of friendship and tend to it with gentle watering and sunlight. She drops into your life, fully formed, and just is. A friend in completion.

Weird.

“Sure,” August says, and she pulls the door open.

There’s no ice to slip on, but Noodles is nearly as determined to make August eat shit on the walk to the station.

“He’s Wes’s, but we all kind of share him. We’re suckers like that,” Myla says as Noodles tugs her along. “Man, I used to get off at Parkside all the time when I lived in Manhattan.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Yeah, I went to Columbia.”

August sidesteps Noodles as he stops to sniff the world’s most fascinating takeout container. “Oh, do they have a good art school?”

Myla laughs. “Everybody always thinks I went to art school,” she says, smacking her gum. “I have a degree in electrical engineering.”

“You—sorry, I assumed—”

“I know, right?” she says. “The science is super interesting, and I’m good at it. Like, really good. But engineering as a career kind of murders your soul, and my job pays me enough. I like doing art more for right now.”

“That’s…” August’s worst nightmare, she thinks. Finishing school and not doing anything with it. She can’t believe Myla isn’t paralyzed at the thought every minute of every day. “Kind of amazing.”

“Thanks, I think so,” Myla says happily.

At the station, Myla waves goodbye, and August swipes through the turnstile and returns to the comfortable, smelly arms of the Q.

Nobody who’s lived in New York for more than a few months understands why a girl would actually like the subway. They don’t get the novelty of walking underground and popping back up across the city, the comfort of knowing that, even if you hit an hour delay or an indecent exposure, you solved the city’s biggest logic puzzle. Belonging in the rush, locking eyes with another horrified passenger when a mariachi band steps on. On the subway, she’s actually a New Yorker.

It is, of course, still terrible. She’s almost sat in two different mysterious puddles. The rats are almost definitely unionizing. And once, during a thirty-minute delay, a pigeon pooped in her bag. Not on it. In it.

But here she is, hating everything but the singular, blissful misery of the MTA.

It’s stupid, maybe—no, definitely. It’s definitely stupid that part of it is that girl. The girl on the subway. Subway Girl.

Subway Girl is a smile lost along the tracks. She showed up, saved the day, and blinked out of existence. They’ll never see each other again. But every time August thinks of the subway, she thinks about brown eyes and a leather jacket and jeans ripped all the way up the thighs.

Two stops into her ride, August looks up from the Pop-Tart she’s been eating, and—

Subway Girl.

There’s no motorcycle jacket, only the sleeves of her white T-shirt cuffed below her shoulders. She’s leaning back, one arm slung over the back of an empty seat, and she … she’s got tattoos. Half a sleeve. A red bird curling down from her shoulder, Chinese characters above her elbow. An honest-to-God old-timey anchor on her bicep.

August cannot believe her fucking luck.

The jacket’s still there, draped over the backpack at her feet, and August is staring at her high-top Converse, the faded red of the canvas, when Subway Girl opens her eyes.

Her mouth forms a soft little “oh” of surprise.

“Coffee Girl.”

She smiles. One of her front teeth is crooked at the slightest, most life-ruining angle. August feels every intelligent thought exit her skull.

“Subway Girl,” she manages.

Subway Girl’s smile spreads. “Morning.”

August’s brain tries “hi” and her mouth goes for “morning” and what comes out is, “Horny.”

Maybe it’s not too late to crawl under the seat with the rat poop.

“I mean, sure, sometimes,” Subway Girl replies smoothly, still smiling, and August wonders if there’s enough rat poop in the world for this.

“Sorry, I’m—morning brain. It’s too early.”

“Is it?” Subway Girl asks with what sounds like genuine interest.

She’s wearing the headphones August saw the other day, ’80s-era ones with bright orange foam over the speaker boxes. She digs through her backpack and pulls out a cassette player to pause her music. A whole cassette player. Subway Girl is … a Brooklyn hipster? Is that a point against her?

But when she turns back to August with her tattoos and her slightly crooked front tooth and her undivided attention, August knows: this girl could be hauling a gramophone through the subway every day, and August would still lie down in the middle of Fifth Avenue for her.

“Yeah, um,” August chokes out. “I had a late night.”

Subway Girl’s eyebrows do something inscrutable. “Doing what?”

“Oh, uh, I had a night shift. I wait tables at Pancake Billy’s, and it’s twenty-four hours, so—”

“Pancake Billy’s?” Subway Girl asks. “That’s … on Church, right?”

She rests her elbows on her knees, perching her chin on her hands. Her eyes are so bright, and her knuckles are square and sturdy, like she knows how to knead bread or what the insides of a car look like.

August absolutely, definitely, is not picturing Subway Girl just as delighted and fond across the table on a third date. And she’s certainly not the type of person to sit on a train with someone whose name she doesn’t even know and imagine her assembling an Ikea bed frame. Everything is completely under control.

She clears her throat. “Yeah. You know it?”

Subway Girl bites down on her lip, which is. Fine.

“Oh … oh man, I used to wait tables there too,” she says. “Jerry still in the kitchen?”

August laughs. Lucky again. “Yeah, he’s been there forever. I can’t imagine him ever not being there. Every day when I clock in it’s all—”

“‘Mornin’, buttercup,’” she says in a pitch-perfect imitation of Jerry’s heavy Brooklyn accent. “He’s such a babe, right?”

“A babe, oh my God.”

August cracks up, and Subway Girl snorts, and fuck if that sound isn’t an absolute revelation. The doors open and close at a stop and they’re still laughing, and maybe there’s … maybe there’s something happening here. August has not ruled out the possibility.

“That Su Special, though,” August says.

The spark in Subway Girl’s eyes ignites so brilliantly that August half expects her to jump out of her seat. “Wait, that’s my sandwich! I invented it!”

“What, really?”

“Yeah, that’s my last name! Su!” she explains. “I had Jerry make it special for me so many times, everybody started getting them. I can’t believe he still makes them.”

“He does, and they’re fucking delicious,” August says. “Definitely brought me back from the dead more than once, so, thank you.”

“No problem,” Subway Girl says. She’s got this far-off look in her eyes, like reminiscing about cranky customers sending back shortstacks is the best thing that’s happened to her all week. “God, I miss that place.”

“Yeah. You ever notice that it’s kind of—”

“Magic,” Subway Girl finishes. “It’s magic.”

August bites her lip. She doesn’t do magic. But the first time they met, August thought she’d do anything this girl said, and alarmingly, that doesn’t seem to be changing.

“I’m surprised they haven’t fired me yet,” August says. “I dumped a pie on a five-year-old yesterday. We had to give him a free T-shirt.”

Subway Girl laughs. “You’ll get the hang of it,” she says confidently. “Small fuckin’ world, huh?”

“Yeah,” August agrees. “Small fucking world.”

They linger there, smiling and smiling at each other, and Subway Girl adds, “Nice scarf, by the way.”

August looks down—she forgot she was wearing it. She scrambles to take it off, but the girl holds up a hand.

“I told you to keep it. Besides”—she reaches into her bag and produces a plaid one with tassels—“it’s been replaced.”

August can feel her face glowing red to match the scarf, like a giant, stammering, bisexual chameleon. An evolutionary mistake. “I, yeah—thank you again, so much. I wanted—I mean, it was my first day of class, and I really didn’t want to walk in looking like, like that—”

“I mean, it’s not that you looked bad,” Subway Girl counters, and August knows her complexion has tipped past blushing and into Memorial Day sunburn. “You just … looked like you needed something to go right that morning. So.” She offers a mild salute.

The announcer comes over the intercom, more garbled than usual, but August can’t tell if it’s the shitty MTA speakers or blood rushing in her ears. Subway Girl points to the board.

“Brooklyn College, right?” she says. “Avenue H?”

August glances up— Oh, she’s right. It’s her stop.

She realizes as she throws her bag over her shoulder: she might never get this lucky again. Over eight and a half million people in New York and only one Subway Girl, lost as easily as she’s found.

“I’m working breakfast tomorrow. At Billy’s,” August blurts. “If you wanna stop by, I can sneak you a sandwich. To pay you back.”

Subway Girl looks at her with an expression so strange and unreadable that August wonders how she’s screwed this up already, but it clears, and she says, “Oh, man. I would love that.”

“Okay,” August says, walking backward toward the door. “Okay. Great. Cool. Okay.” She’s going to stop saying words at some point. She really is.

Subway Girl watches her go, hair falling into her eyes, looking amused.

“What’s your name?” she asks.

August trips over the train threshold, barely missing the gap. Someone collides with her shoulder. Her name? Suddenly she doesn’t know. All she can hear is the whisper of her brain cells flying out the emergency exit.

“Uh, it’s—August. I’m August.”

Subway Girl’s smile softens, like somehow she already knew.

“August,” she repeats. “I’m Jane.”

“Jane. Hi, Jane.”

“The scarf looks better on you anyway.” Jane winks, and the doors shut in August’s face.

Jane doesn’t come to Billy’s.

August hovers outside the kitchen all morning, watching the door and waiting for Jane to sweep through like Brendan Fraser in The Mummy, rakish and windswept with her perfectly swoopy hair. But she doesn’t.

Of course she doesn’t. August refills the ketchup bottles and wonders what demon jumped up inside her and made her invite a hot stranger to tolerate her terrible service on a Saturday morning in a place where she used to work. Just what every public transit flirtation needs: old coworkers and a sweaty idiot dumping syrup on the table. What an extremely sexy proposition. Really out here smashing pussy, Landry.

“It’s fine,” Winfield says once he pries the source of her anxious pacing out of her. He’s only barely paying attention, scribbling on a piece of sheet music tucked into his guest check pad. He has a penchant for handing out cards for his one-man piano and saxophone band to customers. “We get about a hundred hot lesbians through here a week. You’ll find another one.”

“Yeah, it’s fine,” August agrees tightly. It’s fine. It’s no big deal. Only carrying on her proud family tradition of dying alone.

But then Monday comes.

Monday comes, and somehow, in an insane coincidence Niko would call fate, August steps onto her train, and Jane is there.

“Coffee Girl,” Jane says.

“Subway Girl,” August says back.

Jane tips her head back and laughs, and August doesn’t believe in most things, but it’s hard to argue that Jane wasn’t put on the Q to fuck up her whole life.

August sees her again that afternoon, riding home, and they laugh, and she realizes—they have the exact same commute. If she times it right, she can catch a train with Jane every single day.

And so, in her first month in the apartment on the corner of Flatbush and Parkside above the Popeyes, August learns that the Q is a time, a place, and a person.

There’s something about having a stop that’s hers when she spends most days slumping through a long stream of nothing. There was once an August Landry who would dissect this city into something she could understand, who’d scrape away at every scary thing pushing on her bedroom walls and pick apart the streets like veins. She’s been trying to leave that life behind. It’s hard to figure out New York without it.

But there’s a train that comes by around 8:05 at the Parkside Ave. Station, and August has never once missed it since she decided it was hers. And it’s also Jane’s, and Jane is always exactly on time, so August is too.

And so, the Q is a time.

Maybe August hasn’t figured out how she fits into any of the spaces she occupies here yet, but the Q is where she hunches over her bag to eat a sandwich stolen from work. It’s where she catches up on The Atlantic, a subscription she can only afford because she steals sandwiches from work. It smells like pennies and sometimes hot garbage, and it’s always, always there for her, even when it’s late.

And so, the Q is a place.

It sways down the line, and it ticks down the stops. It rattles and hums, and it brings August where she needs to be. And somehow, always, without fail, it brings her too. Subway Girl. Jane.

So maybe, sometimes, August doesn’t get on until she catches a glimpse of black hair and blacker leather through the window. Maybe it’s not just a coincidence.

Monday through Friday, Jane makes friends with every person who passes through. August has seen her offer a stick of gum to a rabbi. She’s watched her kneel on the dirty floor to soften up scrappy schoolgirls with jokes. She’s held her breath while Jane broke up a fight with a few quiet words and a smile. Always a smile. Always one dimple to the side of her mouth. Always the leather jacket, always a pair of broken-in Chuck Taylors, always dark-haired and ruinous and there, morning and afternoon, until the sound of her low voice becomes another comforting note in the white noise of her commute. August has stopped wearing headphones. She wants to hear.

Sometimes, August is the one she hands a stick of gum to. Sometimes Jane breaks off from whichever Chinese uncle she’s charming to help August with her armload of library books. August has never had the nerve to slide into the seat next to her, but sometimes Jane drops down at August’s side and asks what she’s reading or what the gang is up to at Billy’s.

“You—” Jane says one morning, blinking when August steps on the train. She has this expression she does on occasion, like she’s trying to figure something out. August thinks she probably looks at Jane the same way, but it definitely doesn’t come off cool and mysterious. “Your lipstick.”

“What?” She brushes a hand over her lips. She doesn’t usually wear it, but something had to counterbalance the circles under her eyes this morning. “Is it on my teeth?”

“No, it’s just…” One corner of Jane’s mouth turns up. “Very red.”

“Um.” She doesn’t know if that’s good or bad. “Thanks?”

Jane never volunteers anything about her life, so August has started guessing at the blanks. She pictures bare feet on hardwood floors in a SoHo loft, sunglasses on the front steps of a brownstone, a confident and quick order at the dumpling counter, a cat that curls up under the bed. She wonders about the tattoos and what they mean. There’s something about Jane that’s … unknowable. A shiny, locked file drawer, the kind August once learned to crack. Irresistible.

Jane talks to everyone, but she never misses August, always a few sly words or a quick joke. And August wonders if maybe, somehow, Jane thinks about it as much as August, if she gets off at her stop and dreams about what August is up to.

Some days, when she’s working long hours or locked up in her room for too long, Jane is the only person who’s kind to her all day.

And so, the Q is a person.

Fullepub

Fullepub