Chapter 10

10

New Restaurant Lucille’s Burgers Opens in French Quarter

PUBLISHED AUGUST 17, 1972

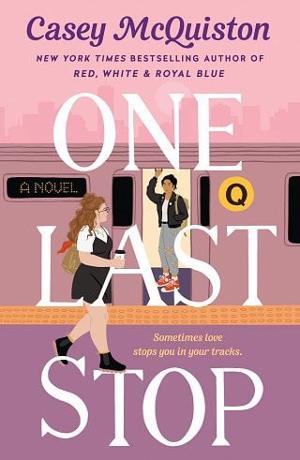

[Photo: An older woman in an apron stands in front of a bar, arms crossed, while a young woman in the background carries a tray of burgers]

Lucille Clement remembers growing up in her mother’s kitchen while waitress Biyu Su delivers orders to customers.

Robert Gautreaux for The Times-Picayune

“So you’re sleeping with Jane?”

August turns, toothbrush in mouth. Niko’s looking at her from the end of the hallway, holding a golden barrel cactus the size of a basketball between two tattooed hands.

She managed to dodge him when she stumbled back into the apartment at five in the morning with her shirt buttoned wrong and the shape of Jane’s mouth bruised onto the side of her neck. But she should have known she could only avoid the resident psychic for so long.

She spits and rinses. “Can you not do that?”

“Sorry, was I skulking? Sometimes I skulk without realizing.”

“No, the thing where you know things about my personal life just by looking at me.” She racks her toothbrush. “But also the skulking.”

He pulls a face. “I don’t mean to, it’s just, like … the energy you put out about Jane. It’s burning a new hole in the ozone layer.”

“You know, the old hole in the ozone layer closed up.”

“I feel that you are deflecting.”

“I can send you a National Geographic article about it.”

“We don’t have to talk about it,” Niko says. “But I’m happy for you. You care so much about her, and she cares so much about you.”

August stares into the mirror, getting the rare chance to watch herself turn pink. It happens in big, unattractive splotches. This is what Jane sees. It’s a miracle she wants to have sex with her.

Sex. She and Jane had sex. She and Jane are, if they can figure out the logistics, possibly going to have more sex. August isn’t a virgin anymore.

She wonders if she should be having some kind of mental journey about that. She doesn’t feel different. She doesn’t look any different, just round-faced and splotchy, like a hard-boiled egg with a sunburn.

“Virginity is a social construct,” Niko says mildly, and August glares at him. He does a vague sorry-for-reading-your-mind gesture. August is going to dropkick his cactus out the window.

“It’s true,” Myla says, head popping out of their bedroom, eyes wide behind her welding goggles, still wearing her satin bonnet from the night before. “The whole idea is based on cissexist and heteronormative and quite frankly colonial-ass bullshit from a time when getting a dick in you was the only definition of sex. If that’s true, me and Niko have never had sex at all.”

“And we both know that’s absolutely not the case,” Niko says.

“Yeah, our walls are thin and I have ears,” August says, heading toward her bedroom in search of something to tie her hair up. “What kind of safeword is ‘waffle cone,’ anyway?”

“Speaking of overhearing things,” Myla presses on, “did I hear Niko say you’re sleeping with Jane?”

“I—” August shoots a perturbed glance at Niko, who has the decency to look as sheepish as he ever does, which is mostly just a slightly less jovial jut of his hips. “You can’t really call it ‘sleeping.’ There’s not really a bed involved.”

“Fucking finally! Like, literally!”

“Lord.”

“Did you make sure she was clean? Can you catch an STI from a ghost?”

“She’s not a ghost,” August and Niko say in unison.

“Okay, still, let me be a mom for a second.”

“Look, yeah, she’s—it’s fine.” August would love for their creaky floorboards to finally open up and drop her out of this conversation. “It’s come up before. I have to keep track of everything she remembers, okay?”

“Oh, yeah, classic getting-to-know-you conversation,” Myla says from across the hall. “What kind of music do you like? Where are you from? Do you now or have you ever had crabs?”

“You just described our first date, verbatim,” Niko points out.

August, still searching for a ponytail holder, picks up her bag and upends it on the bed.

Her blue ponytail holder from last night falls out, and she tries not to think about tying her hair up while Jane’s teeth worried at her skin. With Niko on the other side of the wall, she might as well project a PowerPoint presentation of herself getting railed on the subway for the whole apartment.

She frowns down at the mess from her bag. A pack of batteries? Where did those come from?

“Oh,” she says, realizing. “Ohhhh, bitch.”

God, she can’t believe it took her so long to notice. This is why you aren’t supposed to kiss your case. She fumbles her phone off her desk so fast, she nearly flings it out the open window.

Weird question, she texts Jane, fingers trembling. Distantly, she hears Niko and Myla in the hallway discussing soil brands. Can you open the battery compartment on your radio and tell me what you see?

Nothing? There’s nothing in there. Why?

There are no batteries in your radio?

Nope.

Didn’t you ever wonder how it works?

I figured it was like my cassette player? It doesn’t have batteries either. I’m a sci-fi freak show, I just assumed that was part of it.

You’ve had a magical cassette player all this time and you never thought to investigate?????? Or mention it???????

I don’t know! I told you when I showed it to you that I didn’t know how it worked! I thought you knew!

I thought you meant you didn’t know how it worked because it was so old???

Wow, that’s calling ME old.

asldfjasf if I thought you could die I would strangle you

She slams back out of her room and into the hall, almost getting a faceful of Niko’s cactus.

“Careful! Cecil is sensitive!”

She ignores him, throwing the package down on the floor in front of the alarm clocks Myla has been blowtorching together all afternoon. “Batteries!”

“What?”

“Batteries,” August repeats. “When you sold me that radio, you told me to make sure I put batteries in it. So I bought those, but—but that was in the middle of the whole kissing-induced horniness fog, so I forgot to give them to her.”

“Uh-huh.”

“But it still works. Her radio, her cassette player—shit, her phone, I gave her a portable battery for it weeks ago but I’ve never seen her use it. None of her electronics need batteries to work. So that means—”

“—whatever is keeping her on the train has to do with electricity,” Myla finishes. She shoves her goggles up onto her forehead. “Whoa.”

“Yeah.”

“Wait. Wow. Yeah, that would make sense. It’s not the train, it’s the line. Maybe she’s bound to—”

“The current. The electrical current of the tracks.”

“So—so whatever event threw her out of time—it might have been electrical. A shock, maybe.” She sits back on her heels, sending LaCroix cans rattling across the floor. It’s impossible to tell if they’re for Myla’s project or hydration. “But something like that, the voltage of the line—I don’t understand how it wouldn’t just kill her.”

“And she’s definitely not dead,” Niko helpfully reminds them.

“I don’t know either,” August says. “There must be more to it. But this is something, right? This is big.”

“It could be,” Myla says.

It’s a conversation that goes on for days. August jots down thoughts on her arm in the middle of finals, takes notes during shifts in her guest check pad, meets Myla at Miss Ivy’s to talk it through for the hundredth time.

“You remember the first time I tried to meet her on my own?” Myla says. She’s unpacking a to-go bag full of vegan curry and patties, Niko’s lunch. He’s in the back with a client, and Miss Ivy is on the other side of the shop, watching them warily. “And I couldn’t find her? But when you brought Niko with you, she was there.”

“Yeah,” August says. She glances at Miss Ivy. It’s probably not the weirdest topic ever discussed here. She lowers her voice anyway. “But we’ve all gone down alone and seen her at some point.”

“But not until after you introduced us. You’re the most important point of contact. We can find her because she recognizes us through you.”

“What do you mean?”

“August, you said it yourself—if she doesn’t see you for a while, she starts to come unstuck. It’s not like she’s on every train all the time—she’s flickering to the one you’re on. You’re what’s keeping her here. You’ve watched Lost—you’re her constant.”

August drops down onto a rickety stool, rattling the shelf of crystals behind it. Her constant.

“But … why?” August asks. “How? Why me?”

“Think about it. What are feelings? How does your body communicate to your brain?”

“Electrical impulses?”

“And how do you feel when you look at Jane? When you talk to her? When you touch her?”

“I don’t know. Like my heart is gonna come out of my ass and suplex me into the mantle of the earth, I guess.”

“Exactly,” she says, jabbing a plastic fork in August’s direction. She’s started in on Niko’s curry. If he doesn’t finish communing with the beyond soon, he’s not going to have a lunch. “That’s chemistry. That’s attraction. That’s, like, boner city. And that comes with all these super powerful electrical impulses between your nerve endings, all throughout that big beautiful brain of yours. If we’re right and her existence is tethered to the electricity of the line, then every time you make her feel something, every time you touch her or kiss her, every interaction you have is generating more electrical impulses, which means you’re making her more … real.”

“When we—” August realizes out loud. “The other day, when we—you know—”

“August, we’re adults, just say you got your back blown out.”

Across the room, Miss Ivy unfurls a paper fan like she does when she’s having a hot flash.

“Can you please,” August begs. “Anyway, before, right when I said I wanted to—the train broke down. So, are you saying—?”

A dirty smile dawns on Myla’s face.

“Oh my God. She literally shorted out the train because she was horny,” she says, eyes sparkling with absolute awestruck admiration. “She’s an icon.”

“Myla.”

“She’s my hero.”

“God, so—so that’s … that’s why,” August says. “It’s a feedback loop between her and the line. That’s how she knows when the emergency lights are gonna come on and when they aren’t. That’s why the lights go crazy when she’s upset. It’s all interconnected.”

“And why your insane kissing-for-research plan worked,” Myla says. “The attraction between you two is literally a spark, and it’s the same spark that’s bringing her back into reality. She feels something, the line feels it, electrical impulses in her brain start firing, it pieces her back together. It’s you, August. You’re the reason she’s staying in one place. You’re what’s keeping her here.”

That’s … a lot, August thinks.

Jane texts her that night, Missed you today, and August thinks about her warm mouth and collarbones in the moonlight and wants, but the next day is an exam straight into a late shift. So she takes a different train, and Myla meets her at Billy’s and sits at the counter with a burger, picking up right where they left off.

“Okay, but why me?” August says.

“I thought we had gotten past your denial that she wants to eat chocolate fondue off your ass and then cosign a mortgage.”

“No, I mean, I can believe that she—she likes me,” August says in a tone that sounds like she cannot believe it at all. “But she’s been on that train so long. I’ve found Craigslist posts and personal ads—people have been falling in love with her for years. She really never had a crush on anyone before now? Why was meeting me the first time she locked into a moment in time?”

Myla swallows an enormous bite of beef. It’s not that Niko enforces a vegetarian household, it’s just that Myla enjoys meat more when Niko’s not there to look distantly sad about the environment.

“Maybe you’re meant to be. Love at first sight. It happened to me.”

“I don’t accept that as a hypothesis.”

“That’s because you’re a Virgo.”

“I thought you said virginity was a construct.”

“A Virgo, you fucking Virgo nightmare. All this, and you still don’t believe in things. Typical Virgo bullshit.” Myla puts her burger down. “But maybe there was, like, an extra spark when you met, that pulled the trigger. What do you remember about it?”

God, what does she remember? Besides the smile and kind eyes and general aura of punk rock guardian angel?

She tries to think past that—to the skinned knee, the way she had tugged the sleeves of her jacket over her hands to hide the scrapes, trying not to cry.

“I had spilled coffee all over my tits,” August says.

“Very sexy,” Myla notes, nodding. “I get what she sees in you.”

“And she gave me her scarf to cover it up.”

“Dream girl status.”

“I do remember there was, like, a static shock, when I reached for the scarf and our hands brushed, but I was wearing wool and the scarf was wool and I just never thought anything of it. Do you think that was it?”

Myla considers. “Maybe. Or maybe that was a side effect. Energy going nuts. Anything else?”

“I had just come from work, and she told me I smelled like pancakes.”

“Oh. Hm.” She uncrosses her legs, leaning forward across the counter. “She used to work here, right?”

“Right.”

“And this place does have a … very particular smell, right?”

“Right…” August says. “Oh. Oh! So you think it was a sense memory? Like she recognized Billy’s?”

“Smell is the strongest memory trigger. Could have done it. Maybe it was the first time she encountered something she really recognized on the train.”

“Seriously?” August lifts the collar of her T-shirt to her nose. “Wow, I’m never gonna bitch about smelling like pancakes again.”

“You know,” Myla says, “if we can figure out what happened, exactly how her energy got tied into the energy of the line, and we can re-create the event…”

August drops her shirt collar. “We could undo it? That’s how we get her out?”

“Yeah,” Myla says. “Yeah, I think it could work.”

“And—and she snaps back to the ’70s for good?”

Myla thinks. “Probably. But there’s a chance … I mean, there aren’t really any rules in this. So who knows? Maybe there’s a chance she could lock into right here, right now.”

August stares at her. “Like … permanently?”

“Yeah,” Myla says.

August allows herself five seconds to picture it: Jane’s jeans tangled up in August’s laundry, late nights and split bills, kisses on the sidewalk, oversweet coffee in bed.

She shakes the idea out, turning back to the register. “She probably won’t, though.”

That afternoon, August finally makes her way to the Q. She didn’t mean to go three days without seeing Jane after they had sex, honestly—she just got caught up in the case. It has absolutely nothing to do with how Jane kissed her for real inside a perfect moment in the middle of the night and August doesn’t know how to approach this inside a normal Thursday afternoon.

On her way to the platform, she sees the sign. Same warning, same deadline: September. The Q is closing in September. She could lose Jane forever in September. And even if she figures things out, she’ll probably lose Jane anyway—to the ’70s, her own time.

So, there’s that, and there’s the very fresh memory of gasping into oblivion on the Manhattan Bridge, and there’s the idea that whatever they are to each other is what makes Jane real, and there’s August, standing on a platform, trying to file each thing neatly away into different file drawers in her brain.

It’s crowded today, but Jane’s sitting, tucked at the end of a bench between the back wall of the car and someone’s towering Ikea haul.

“Hey, Coffee Girl,” Jane says when August manages to wedge her way between commuters. August tries to read her face, but her features assemble into her usual expression: gentle amusement, like she’s thinking of a half-remembered joke at nobody’s expense.

August wants to kiss her mouth again. August, inconveniently, wants to do a lot of things again.

“Where’ve you been?” Jane asks.

“Sorry, I didn’t mean to—I had this big breakthrough with your case, and finals, everything was nuts, but—anyway, I have a lot to catch you up on.”

“Okay,” Jane says placidly. “But can you come down here and tell me?”

“What—” August starts, before Jane grabs her and pulls her down. She thumps gently into Jane’s lap. “Oof. Hello.”

Jane grins back. “Hi.”

“Oh, it’s nicer down here,” August says.

“Yeah, I made reservations.”

There’s a certain threshold at which a packed subway car goes from too personal to completely impersonal, so many people that they blend together and nobody takes notice of anyone else. In Jane’s little pocket of bench, surrounded by backpacks and turned backs and boxed-up Björksnäs units, it almost feels private.

August settles in, bundling her jean jacket into her lap. Her skirt has fanned out behind her, draping over them both, and she’s acutely aware of the way Jane’s denim feels against her bare thighs, the rips that allow skin to touch skin.

“What?” Jane says, studying her face. August imagines the look on it: a combination of uptight and turned on, which pretty much sums her up.

“I need to tell you about the case,” August says.

“Uh-huh,” Jane says. “But what?”

“You know what.”

One of Jane’s hands travels up, spanning the top of August’s thigh. August looks at her, and something tugs in her chest, and she wonders if that’s it—the electricity. Desire and chemistry coiled up inside something bigger, something deeper and softer.

“Listen,” Jane says. “You can’t look at me like that and not tell me what you’re thinking.”

“I’m thinking—” August starts, and the thing in her chest tugs harder, and she can’t. She can’t say that whatever is between them is the reason this is happening at all. If she says it, she’ll break it. “I’m thinking about you.”

Jane narrows her eyes. “What about me?”

“About … the other night.” Not a complete lie.

“Yeah,” Jane says. “I guess we haven’t talked about it.”

“Do we have to?”

“I guess not,” she replies, her thumb stroking a curved line up the inside of August’s leg. “But we should talk about what you want.”

And it’s … God. August can feel it: the way things have shifted, the intent that sparks off of Jane like flint, the way she rakes her eyes down from August’s mouth to her throat like she’s thinking about the mark she left there. August came down here to debrief, but she might as well be unbuttoning her shirt for how present her brain is.

Is this what it’s always like? To want someone and know they want you back? How in the world does anyone get anything done?

“I want to talk about the case.” August wants to scream. Spiritually, she is screaming.

Jane’s hand pauses. “Okay.”

“It’s—it’s super important. Really big stuff.”

“Sounds like it.”

“But.”

“Yeah,” Jane says. Their eyes meet. God, it’s hopeless.

“This whole thing we have going on is … it’s very bad for my productivity,” August says.

“What exactly do we have going on?” Jane asks her. “You still haven’t told me.”

“The thing where I wanted you for months, and then I had you, and now I want you all the time,” August says before she can stop herself. She feels her face go pink. “We’re on a deadline, and it’s distracting.”

Jane’s smiling, her eyes whiskey brown and full of trouble.

“All the time?” Jane says. “Like … right now?”

Yeah, definitely trouble.

“I mean,” August says, “not necessarily right now.” Yes, right now. Right now all the time always. “I have to tell you about the case.”

“Sure,” Jane says. But her fingertips slide under the hem of August’s skirt. It startles a soft gasp out of her, and Jane says quietly, “I’ll stop any time you tell me to stop.”

She moves as if to pull her hand away, and August holds her wrist down on reflex.

“Don’t stop.”

“Okay, then,” Jane says. “You tell me about the case, and I’ll…” Her hand disappears beneath the fabric pooled in August’s lap. “Listen.”

August swallows. “Right.”

She talks about the electricity and the tracks, holding just enough back—the parts about the connection between the two of them—and Jane listens quietly as she unravels their ideas about feedback loops and feelings and memories.

“So,” August goes on, “if you can remember what exactly happened that got you stuck here, maybe there’ll be a way to re-create the event and undo it. Like a manual reboot.”

“Knock me back into place,” Jane says.

“Yeah,” August agrees. “And then … then, theoretically, we could get you back to the ’70s. Where you’re supposed to be. Unless we can’t figure it out, then … well, it doesn’t matter. I’ll figure it out.”

“Okay,” Jane says. Her eyes have gone a little distant.

“So, we have to get you to remember what happened the day you got stuck here.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Any ideas how we might do that?”

Jane hums, her hand sliding higher, hidden completely under August’s skirt and the jacket in her lap. “I have a lot of ideas, actually.”

“I—” August stutters. “I don’t understand how you’re so laid-back about this. It’s your existence on the mortal plane.”

“Look,” Jane says, fingers spreading to grip right below her ass. August’s hand tightens on Jane’s collar. “If you’re right, I’m here for a good time, not a long time. So, maybe I want to have a little fun. It doesn’t always have to be so serious.”

August thinks about the tally marks, the girls Jane kissed in every city, and she wonders if this is all Jane really wants from her. Maybe August is different from the other girls, but Jane is still Jane, loving with firecracker quickness, using her hands and her mouth and half of her heart. A good time. Nothing serious.

And August, who has spent most of her life taking everything seriously with the occasional detour into cynical jokes for survival, has to admit—Jane has a point.

“Okay,” August says. “You got me.”

“I know I got you,” Jane says, and there it is: the dull scrape of short nails against the cotton of August’s underwear.

Fuck.

“Jane,” she says, even though nobody around is remotely paying attention.

Jane’s hand stills carefully, but she leans up, into August’s neck, lips brushing her earlobe when she says, “Tell me to stop.”

And August should. August should tell her to stop.

She should really want to tell her to stop.

But Jane’s fingertips are brushing against her, teasing out her nerve endings and making her hips ache, and she thinks about all the months of wanting honed down to an exquisitely fine point, sharp against her skin until it feels like it could draw blood.

Caution and a knife. She used to swear by it. But this is sharper, and she doesn’t want it to stop.

So when Jane’s thumb swipes up under the cotton, and Jane looks into her eyes for an answer, August nods.

The thing about Jane is, she’s exactly what August isn’t, and it works. Where she’s soft, Jane is hard. Where she’s harsh and prickly and resistant, Jane is all generous smiles and ease. August is lost in something dangerously like love, and Jane is laughing. And here, between stops, between her legs, she’s anxious and tense and Jane is confident and smooth, dragging her fingers, finding her way, slick and maddening.

Her mind is softening at the edges, sinking into the feeling of not having to be in control, letting Jane push her right to the edge of her limits.

“Keep talking, angel,” Jane whispers in her ear.

“Uh—” August stammers, struggling to keep a blank face. Jane’s middle finger does a tight circle and August wants to push into it, press down, but she can’t move. She’s never been so thankful for people who bring Ikea furniture on the subway. “Shit.”

She feels the warm burst of Jane’s quiet laugh against the side of her neck.

“We could—” August attempts. It takes everything to keep her voice level. “We could try rebuilding everything from summer of ’76 on. I can break—fuck—um, into the office at Billy’s and see if there’s—oh—uh, if they have any records that would be helpful.”

“Breaking and entering,” Jane says. The car sways into daylight, and August has to dig her fingernails into Jane’s knee to keep her composure. “Do you know how hot that is?”

“I’m, uh—” A short gasp. She can’t believe this is happening. She can’t believe she’s doing this. She can’t believe she ever has to stop doing this. “I guess criminal behavior isn’t as much of a turn-on for me.”

“That’s interesting,” Jane says conversationally. “Because it seems like doing things you’re not supposed to do kind of gets you off.”

“I don’t know if you have enough—ah—evidence to support that theory.”

Jane leans in and says, “Try not to come, then.”

And August thinks, she has to find a way to get Jane out of here, just so she can kill her.

It goes slow at first—from the tension in Jane’s shoulder, it’s obvious she can’t move like she wants to, so she settles for working short and precise and deadly—until it doesn’t, until it’s quick and shallow and August is talking, trying to make words happen from her mouth, to swallow down sighs, trying not to look at Jane looking at her. It’s the stupidest thing she’s done since she jumped between train cars, but somehow it feels like her body finally makes sense. She bites her lip through the build, the whiteout, her eyes screwed shut and her hips burning from the effort not to move. Jane kisses the side of her neck, beneath her hair.

“Well,” Jane says casually. August’s cheeks are burning a furious pink, and Jane looks coolly unfazed, except for her pupils, which are blown wide. “It sounds like you have a pretty good plan.”

So that’s how things will be, August deduces as she walks home, goodbye kiss lingering on her lips. She works the case, and Jane kisses her, and they talk about the first thing but not the second.

Sometimes it feels like there are three Augusts—one born hopeful, one who learned how to pick locks, and one who moved to New York alone—all sticking out knife blades and tripping one another to get to the front of the line. But every time the doors open and she spots Jane at the far end of the car, listening to music that shouldn’t even be playing, she knows it doesn’t make a difference. Every possible version of August is completely stupid for this girl, no matter the deadline. She’ll take what she can get and figure out the rest.

She gets to be an adult who has sex, sex with Jane, and Jane gets to feel something that’s not boredom or waiting, and it’s fun. It’s good, so good that August’s mouth will start watering in the middle of a graveyard shift at Billy’s just thinking about it. Jane seems happier, which was the point, she reminds herself.

They’re friends. Cross-timeline friends with semi-public benefits, because they’re attracted to each other and lonely and there, and August has learned to like feeling a little reckless. She never thought she was meant for any kind of danger until she met Jane.

Not that she’s meant for Jane.

She tells herself very seriously that if anyone is meant for anything, it’s Jane meant for the ’70s. That’s the job. That’s the case.

That’s all.

August starts a sex notebook.

It’s not that they’re having that much sex. When one person lives on the subway and the other is busting their ass to get them off the subway, there are only so many opportunities.

But she’s used to taking notes on Jane, and, well, it never hurts to have a reference guide. So, she starts a notebook to catalogue everything she discovers that Jane likes.

She starts with the things she already knew. Hair pulling (giving and receiving), August writes at the top of the first page. Below it, lip biting, followed by thigh highs, and, leaving marks. She pauses, sucks on the end of her pen, and adds, semi-public sex* and notes at the bottom of the page, *unsure if always into this or simply making best of situation.

She keeps it in her bag alongside the other notebooks for geographic locations (the green one), biographical anecdotes (blue), and dates and figures (red), and she updates it meticulously. If she doesn’t have it on her, she’ll write on her hand, which is how she ends up having to explain to Winfield in the middle of a shift why she has the words neck biting scrawled from her first to third knuckles.

Sometimes she adds things that aren’t sex but turn Jane on anyway. Long hair makes the list the third time she catches Jane watching her tie her hair up. One afternoon, she goes on a five-minute tangent about UV light and document facsimiles only to find Jane staring at her with her mouth halfway open and her tongue resting wetly between her teeth, and she pulls out the notebook and writes, niche technical expertise + competence.

Most of the items, though, are pretty straightforward. She boards the Q in the middle of the night wearing a pair of fishnets to test a theory, and when she stumbles off an hour later kiss-drunk with the thin strings of nylon ripped in two places, she adds, lingerie.

“We’d meet at Max’s,” Jane’s saying over the phone as August stuffs a load of darks in the coin-operated washer. They’ve been embroiled in a conversation for a day and a half about how they would have met if August had lived in Jane’s 1970s New York. August keeps insisting they’d have a longstanding feud over the library’s last copy of The Second Sex. Jane disagrees.

“You think I’d be at one of your satanic punk shows?” August asks, closing the door and sitting on a dryer.

“Yeah, you’d wander in all lost and confused. Short skirt, long hair, hugging the wall, and I’d come stumbling out of the pit with a bloody nose, see you, and that’d be it.”

August huffs a laugh, but she can picture it: Jane swaggering out of the crush of bodies like a shooting star, snarling and wiping blood on the back of her hand, eyes rimmed with kohl and the collar of her shirt smeared with someone else’s lipstick.

“What’d be your line?” she asks.

Jane makes a considering noise. “Keep it simple. Ask you for a smoke.”

“But you don’t smoke,” August points out.

“And you don’t have a smoke,” Jane says. “I never thought you would. But I had to get real close for you to hear me over the music, and now you’re looking at me, and when I kiss you, it tastes a little like blood.”

“Uh-huh,” August says, heat flaring up the back of her neck. She crosses her legs, squeezing her thighs together. “Keep talking.”

By the time the buzzer announces the end of the wash cycle, Jane’s described in quiet detail just how she’d get August into the bathroom at Max’s, the black leather dog collar she used to wear at shows, and the way she’d let August slip her fingers under it when she got on her knees. August pulls her skirt back down, takes the notebook out, and writes, blood & bruises. Then light bondage. She goes back up several lines and underlines semi-public sex.

June moves through New York like one of Miss Ivy’s hot flashes, steaming up windows and slowing traffic to a tempermental crawl. It’s a decidedly unsexy time, and yet—

“I can’t believe you don’t sweat,” August says, neck-deep in a heatwave at one in the morning, her hands braced against the wall of an empty train car. Jane kisses her hair, slips her thumb under the hem of August’s Billy’s T-shirt. “I’m out here dying, and you look like something out of a movie.”

Jane laughs and swipes her tongue against the side of August’s neck. “It tastes nice on you, though.”

“You know, if you’re going to go around being a whole metaphysical anomaly, you should have, like, control over your magical powers.” She opens her eyes as Jane turns her around and pulls her in. “You should be able to stop the train whenever you want. Or conjure things. Like a couch. That would be nice.”

“Are you saying subway seats aren’t good enough for you?” Jane teases. “This is my house.”

“You’re right, I’m sorry. I really love what you’ve done with the place. And the view, well.” She looks at Jane’s kiss-swollen lips. Outside the window: nothing but brown tunnel walls. “You can’t beat it.”

“Hmm,” Jane says. “Nice try.”

She stomps home forty-five sweaty, delirious minutes later, Jane still laughing in her ear, and she whips her shorts across her bedroom and furiously adds to the list, orgasm denial.

(Jane makes it up to her eventually.)

August guesses it’s predictable that this is how a person like her would handle entry into the mythical ranks of sex-havers—itemized lists, shorthand, the occasional unhelpful diagram. But it’s not her usual compulsive need to organize. It’s the way Jane kisses her like she’s trying to know everything about her, the revelation of what her own body can do, the way Jane’s willing to work for it in five stolen minutes between stops. August wants to give that back to her, and the August way is having a plan of exactly how.

So, she scrapes together tips to buy Jane a new phone, one that can send and receive grainy photos, and she plucks up the courage to take one in her bedroom mirror. She stares at it on her phone, at the hair falling down her shoulders, the lips painted red, the lace, the fading mark on her neck turned up to the light from the window, and she almost can’t believe it’s her. She didn’t know she had it in herself to be this until Jane pulled it out of her. She likes it. She likes it a lot.

She hits send, and Jane texts back a string of swears, and August bites a smile into her pillow and writes, red lipstick.

In between, she picks the lock on the back office of Billy’s and discovers it hasn’t been used since 2008. It’s no more than an ancient filing cabinet of yellowing paystubs and an empty desk, prime real estate for a secondary caseworking outpost. So that’s exactly what she turns it into, deep in the back of the restaurant where nobody notices if she spends her breaks on science fiction storytime. She pins copies of her maps to the walls and thumbs through the files until she finds Jane’s application from 1976. She spends a long minute with that one, running her fingers over the letters, but pins it up too.

She uses Jane’s real name to finally find her birth certificate—May 28, 1953—and since Jane knows she’s twenty-four, they narrow down the timeframe of the event that got her stuck to between summer 1977 and summer 1978.

She makes two copies of a timeline and posts one in her room and the other in the office. Summer 1971: Jane leaves San Francisco. January 1972: Jane moves to New Orleans. 1974: Jane leaves New Orleans. February 1975: Jane moves to New York. Summer 1976: Jane starts working at Billy’s. Everything after: question mark, question mark, question mark.

She scores a boom box from Myla’s shop, a silver ’80s-era Say Anything–style thing. She hides it in the office and tunes it to their station. When she’s too busy for the Q, Jane sends her songs.

August starts sending songs back. It’s a game they play, and August pretends not to look up every lyric of every song and agonize over the meanings. Jane requests “I Want to Be Your Boyfriend,” and August answers with “The Obvious Child.” August calls in “I’m on Fire,” and Jane replies with “Gloria,” and August thumps her head back against the brick wall of the office and tries not to sink through the floor.

“What, exactly,” Wes asks, sitting at the counter with a plate of French toast and watching August doodle a cartoon subway train in the margin of the Sex Notebook, “are you doing?”

“Working,” August says. She ducks automatically as Lucie passes with a tray over her head.

“I meant with Jane,” he says.

“Just having fun,” August says.

“You’ve never just had fun in your life,” Wes points out.

August puts her pen down. “What are you doing with Isaiah?”

Wes shovels an enormous bite into his mouth instead of answering.

Something keeps bothering her about Jane’s name. Her first one, Biyu. Biyu Su. Su Biyu.

She’s repeated it over and over in her head, run it through every database, stared at the cracks in her ceiling trying to pry it out of the filing cabinets of her brain. Where the hell has she heard that name before?

She flips through her notes, returning to the timeline she’s sketched out.

Why does Biyu Su sound so familiar?

If this weren’t so insane, and if she thought her mom wouldn’t drag her back into the black hole of the Uncle Augie investigation, she’d ask her for help. Suzette Landry may not have found what she’s looking for, but she’s good. She’s solved two unrelated cold cases in the course of her work. She plays dirty, she knows her shit, and she never lets things go. It’s the best and worst thing about her.

So when she answers her mom’s nightly phone call—the one she’s been sending to voicemail for a couple of hazy weeks—she doesn’t plan on bringing Jane up. At all.

But her mom knows.

“Why do I get the feeling there is something you’re not telling me?” August can hear the shredder in the background. She must have gotten her hands on some files she’s not supposed to have. “Or someone?”

“I—”

“Oh, it’s a someone.”

“I literally said one syllable.”

“I know my kid. You sound like you did when Dylan Chowdhury accidentally put his promposal note in your locker junior year and then asked for it back so he could give it to the girl two lockers down.”

“Oh my God, Mom—”

“So who is he?”

“The—”

“Or she! It could be a she! Or a … they?”

August doesn’t even have it in her to be moved at how hard she’s trying to be inclusive. “It’s nobody.”

“Cut the shit, kid.”

“Okay, fine,” August says. Once her mother wants an answer, she won’t stop until she gets it. “There’s a girl I met, um, on the subway. That I’ve kind of been seeing. But I don’t think she wants anything serious. She’s not exactly … available.”

“I see,” her mom says. “Well, you know what my policy is.”

“Never go to a second location with someone unless you’ve checked their trunk for weapons first,” August monotones.

“You can mock it all you want, but I’ve never been murdered.”

August could explain that Jane can’t even leave the subway, but instead, she shifts and asks, “What about Detective Primeaux? Is he still a shit?”

“Oh, let me tell you what that smarmy fuck said to me last time I called,” she says, and she’s off.

August switches her phone to speaker, letting her mom’s voice blur into white noise. She goes over the timeline as her mom talks about a lead she’s tracked down, that Augie could have passed through Little Rock in 1974, and she thinks about Jane’s name. Su Biyu. Biyu Su.

“Anyway,” her mom says, “there’s an answer out there somewhere. I’ve been thinking about him so much lately, you know?”

August looks at her bedroom wall, at the photos pinned up with the exact brand of pushpin her mom once used to poke holes in their living room. She thinks about her mom, consumed by this person who can’t ever come back, living and dying by this mystery that doesn’t have a solution. Orienting her entire life around a ghost.

“Yeah,” August says.

Thank God she’s nothing like that.

“Does my lipstick look okay?” Myla says, turning sideways to blink at August. Her elbow knocks Wes’s phone out of his hands, and he grumbles as he retrieves it from the subway floor.

“Hang on,” Jane says, leaning across to fix a smudge of bright blue lipstick with the edge of her thumb. “There. Now you’re perfect.”

“She’s always perfect,” Niko says.

“Gross,” Wes groans. “You’re lucky it’s your birthday.”

“It’s my birthdaaaay,” Niko singsongs happily.

“The ripe old age of twenty-five,” Myla says. She kisses him on the cheek, effectively smudging her lipstick again.

Niko straightens the red bandana around his neck like a cowboy sauntering out of a saloon. He’s wearing denim on denim, a thrifted jean jacket from which he ripped an American flag patch to stitch on a Puerto Rican flag in its place. A Boricua Springsteen on the Fourth of July. It is, in fact, the Fourth of July.

“So what exactly is Christmas in July?” August asks, tugging at the hideous Valentine’s Day T-shirt she picked up from Goodwill. It has a picture of Garfield surrounded by cartoon hearts and says I’LL BE YOUR LASAGNA. It took two tries to explain it to Jane. “And why is it Niko’s birthday tradition?”

“Christmas in July,” Myla says grandly, with a broad gesture that knocks Wes’s phone back to the floor, “is an annual Fourth of July tradition at Delilah’s in which we celebrate the birthday of this great nation”—she does a jerk-off gesture and Niko boos—“with themed beverages and an all-star lineup of drag royalty doing holiday-themed performances.”

“It’s not just Christmas, though,” Niko notes.

“Right,” Myla adds. “They still call it Christmas in July, but it’s evolved to include all holidays. Last year, Isaiah did a Thanksgiving dessert burlesque number to ‘My Goodies’ and wore sweet potato titty tassels and an apple pie g-string. It was amazing. Wes just, like, walked out of the building and sprinted ten blocks.”

“That is not what happened,” Wes says. “I went out for a smoke.”

“Sure.”

“It’s also how Myla and I met,” Niko adds.

“Really?” Jane asks.

“You never mentioned that,” August says.

“Yeah, I used go to Delilah’s all the time when I was still living with my parents,” Niko says. “Everyone there has always been really cool about whatever you are or want to be or think you might be. Good energy.”

“And I was dating one of the bartenders,” Myla finishes.

“Whoa, wait.” August turns to Myla. “You were with someone else when y’all met?”

“Yep,” Myla says, cheerfully adjusting her sweater, a hideous Hanukkah relic from Wes’s childhood. “I don’t want to say I dumped the guy on the spot when I saw Niko, but … I mean, we did have to wait for him to quit bartending before we could show our faces there again.”

“The path of the universe,” Niko says sagely.

“The path of my boner,” Myla echoes.

“Yeah, I’m gonna tuck and roll,” Wes says, maneuvering for the emergency exit.

“That’s so nuts,” Jane says, deftly catching him by the collar of his shirt. “I can’t picture either of you with anyone else.”

“I don’t think we ever really were with anyone else,” Niko says. “Not all the way. I don’t think we could have been.”

“Let go of me. I deserve to be free,” Wes says to Jane, who boops him on the nose.

“Anyway,” Myla says. “We met on Niko’s birthday, at Christmas in July. And we met Isaiah a couple of Christmas in Julys later, and he helped us get the apartment. And so, it’s the birthday tradition.”

“And what a tradition it is,” Niko says.

“God,” Jane says, her smile going soft around the edges. “I wish I could go.”

August touches the back of her hand. “Me too.”

They pull up to their stop and elbow their way toward the doors, and when August is stepping off, she hears Jane say, “Hey, Landry. Forgot something.”

August turns, and Jane’s standing there under the fluorescents with her jacket falling off one shoulder and her eyes bright, looking like something August made up, like a long night and sore legs in the morning. She leans out of the car, just barely, just enough to piss off the universe, and she hauls August in by the front of her idiot T-shirt and kisses her so hard that, for a second, she feels sparks down her spine.

“Have fun,” she says.

The doors shut, and Myla lets out a low whistle. “Goddamn, August.”

“Shut up,” August says, cheeks burning, but she floats up the stairs like she’s on the moon.

Like Slinky’s, Delilah’s is underground, but where Slinky’s has only a grease-stained C from the health department marking the entrance, Delilah’s is all neon, radiant cursive. A flashing pink arrow points down, and the bouncer looks like Jason Momoa with Easter bunny ears. He waves them toward the beaded curtain, and the world explodes into Technicolor.

Floor to ceiling, wall to wall, Delilah’s is decked out in rainbows of Christmas lights, shining Valentine’s hearts, shimmering streamers in red, white, and blue, rows of enormous jack-o’-lanterns stuffed with green and purple string lights, blazing Eid lanterns along the rafters. There’s an oversized menorah on the bar, star-shaped pinatas dangling over the tables, and—startling a loud laugh out of August—Mardi Gras beads flung on nearly every available surface. And not the dollar-store plastic ones, the good ones, the ones you’d shoulder check a child on Canal Street for.

But it’s not the decor that has the room lit up with life. It’s the people. August can see what Niko meant: it has good energy.

You could throw an eggnog—one of the festive shots being passed around on trays—in any direction and hit a different kind of person. Butches, femmes, six-foot beefcakes, Pratt students with terrible haircuts, the type of petite tattooed twenty-somethings Wes refers to as “Bushwick twinks,” women with Adam’s apples, men without them. People who don’t fit into any category but look as happy and wanted here as anyone else, bobbing their heads to the house music and gripping drinks with painted nails. It smells like sweat, like spilled whiskey, like a million sweet perfumes applied in tight three-bedroom apartments like August’s in giddy anticipation of being here, somewhere people love you.

Jane would love this, August thinks.

The bar staff apparently has no grudge against Myla, because one of them nearly vaults the bar when they see her, reindeer onesie and all. Within seconds, there are four glasses of a suspiciously piss-colored concoction on the bar.

“Apple cider margaritas,” the bartender says cheerfully. They spin around and produce four shots like some kind of liquor magician. “And a round of our world famous Oh Shit shot, on the house, for my favorite babes.”

“Thanks, Luz,” Myla coos. “This is our new kid. August. We adopted her in January.”

“Welcome to the family,” Luz tells her, and a drink and a shot are in her hands, and she’s whisked away toward a booth just vacated by a herd of surly goths in perfunctory Halloween headwear.

“To Niko,” Myla says, raising her shot. “Born on the Fourth of July with both fingers in the air, pissing middle America off by living their dream: looks great in jeans and has a hot girlfriend.”

“To family,” Niko says. “And viva Puerto Rico libre.”

“To alcohol,” Wes adds.

“To Hanukkah sweaters,” August finishes, and they all throw it back.

The shot is awful, but the drink, it turns out, isn’t half bad, and the company is great. Niko is in rare form, long limbs stretched out and head cocked, exuding honey-smooth blue-collar boyishness. Molten moonshine. He looks like he could jumpstart a jet engine with his heart.

Beside him, Myla is glowing, the piercing in her nose sparkling. Niko’s usually clean-shaven, but tonight there’s stubble on his chin, and Myla scrapes her nails across it, looking wicked. August makes a mental note to find her headphones before bed.

“They’re like,” Wes says to her in a low voice, “gonna get married, probably.”

“They basically already are.”

“Yeah, except they live with us,” he says.

August glances over. Wes is sitting cross-legged in his usual skinny jeans and baggy T-shirt, topped off with an angel halo Myla shoved onto his head on the way out the door. He looks like a pissed-off cherub.

“They’re not gonna leave us if they get married, Wes,” August tells him.

“Maybe,” he says. “Maybe not.”

“What are you making that face about?” Myla half-shouts across the table.

“Wes thinks we’re gonna get married and move out, and he’ll never see us again,” Niko says. Wes glowers. August can’t help laughing.

“Wes. Wes, oh my God,” Myla says, laughing too. “I mean, yes, we’ll probably get married one day. But we would never leave you. Like we could even afford to. Like we’d even want to. Maybe one day we’ll all move out and get our own places with our own people but, like, even then. We’ll be weirdly codependent neighbors. We’ll all move into a compound. Niko was born to be a cult leader.”

“You say that now,” Wes says.

“Yeah, and I’ll say it then, you punk-ass bitch,” Myla says.

“I’m just saying,” Wes says. “I’ve seen, like, ten different engagement announcements on Instagram this month, okay? I know how it goes! We all age out of our parents’ insurance, and all of a sudden your friends stop having time to hang out because they have a person and that’s their best friend now, and they have a kid, and they move to the suburbs and you never see them again because you’re a lonely old spinster—”

“Wes! First of all, we already have two kids.” She gestures significantly across the table at him and August.

“Rude, but fair,” August says.

“Second of all, we would never move to the suburbs. Maybe, like … Queens. But never the suburbs.”

“I don’t think I’m allowed back on Long Island after I dropped that jar of spiders on the LIRR,” Niko says.

“Why did you—” August starts.

“Third of all,” Myla plows on, “there’s nothing wrong with being alone. A lot of people are happier that way. A lot of people are supposed to be that way. But I don’t think you will be.”

“You don’t know that.”

“Actually, despite your best efforts at this whole one-man production of Cask of Amontillado in which you’re both Montresor and Fortunato, I’m pretty sure you’re gonna find love. Like, good love.”

“What makes you so sure?”

“Two main reasons. One, because you’re a fucking prize.”

He rolls his eyes. “And the second?”

“He’s walking up behind you.”

Wes whips around, and there is Isaiah, makeup done, wearing a vibrant fuschia scarf around his head and laughing with a couple in matching Pilgrim costumes. He glances over, and August knows the second his eyes lock on Wes’s, because it’s the second Wes starts trying to climb under the table.

“Absolutely not, bruh,” Myla says, throwing a kick. “Stand and face love.”

“I don’t understand why you’re doing this when he literally lives across the hall from us,” August says. “You see him all the time.”

“Says August of the six-month-long gay panic.”

“How did this become a roast of me? Wes is the one under the table!”

“Oh,” Niko says simply, “he’s freaking out because they slept together after the Easter party.”

The top of Wes’s head pops up from under the table, along with one accusatory finger.

“Nobody asked the fucking Long Island Medium.”

Niko smiles. “Lucky guess. My third eye is closed tonight, baby. But thanks for confirming.”

Wes gapes at him. “I hate you.”

“Apartment 6F!” says a silky voice, and there Isaiah is, one foot into Annie, painted for the gods, all devastating cheekbones and dark, glittering eyes. “Whatcha doin’, Wes?”

Wes blinks for a full three seconds before loudly exclaiming, “Oh, here it is!” He waves his phone in front of his face. “Dropped my phone.”

Myla snorts as Wes clambers out from under the table, but Isaiah just smiles. August doesn’t know how he does it.

“Well, glad y’all came out. It’s gonna be a good one!” Isaiah says. He adds ominously: “Hope you brought a poncho.”

He’s gone with a flourish of his robe, flashing a nice, long view of leather leggings and an ass produced by dancing in heels and doing squats to fill out catsuits. Wes makes a sound of profound suffering.

“Hate to see him go, hate to watch him leave,” he mumbles. “It’s all terrible.”

August leans back, looking sideways at Wes as he dedicates himself to picking at the label on his beer and emanating an air of abject misery.

“Wes,” August says. “Have you ever heard of a hairy frog?”

Wes eyes her with suspicion. “Is that, like … a sex act?”

“It’s a kind of frog,” she tells him. He shrugs. She swirls a crumpled lime around her drink and continues. “Also known as a Wolverine frog, or a horror frog. They’re this weird-looking subtropical species that are super defensive of themselves. When they feel attacked or threatened, they’ll break the bones in their own toes and force the fragments through their skin to use as claws.”

“Metal,” Wes says flatly. “Is there a reason you’re telling me this?”

August waves her hands in a come-on, it’s-right-there sort of gesture. He purses his lips and carries on fingering the label of his beer. He looks faintly green in the bar lights. August could strangle him.

“You’re the horror frog.”

“I—” Wes huffs. “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“What, being abrasive and emotionally shut off because you’re afraid of wanting something? Yeah, I have no idea what that’s like.”

The night goes on, a blur of cheek kisses, a bathroom with Sharpie and lipstick graffiti that says GENDER IS FAKE and JDMONTERO REARRANGED MY GUTS, people with hairy legs jutting out of pleated skirts, a lipstick-stained joint making the rounds. August drifts into the crowd and lets it buoy her back: this way is the stage, someone flitting around the edges setting up dry ice and confetti cannons, and this way is Lucie, rare smile across her face, and that way is the bar, sticky with spilled shots, and—

Wait.

She blinks through the flashing lights. There’s Lucie, hair down and smudgy eyeliner shot through with glitter that makes her eyes look crazy blue. August doesn’t even realize how close she is until acrylic nails are digging into her shoulders.

“Lucie!” August shouts.

“Are you lost?” she shouts back. “Are you alone?”

“What?” Lucie’s face is sliding in and out of focus, but August thinks she looks nice. Pretty. She’s wearing a shimmery blue dress with a fur shrug and shiny ankle boots. August is so happy she’s here. “No, my friends are over there. Somewhere. I have friends, and they’re here. But oh my God, you look amazing! It’s so cool you came to Isaiah’s show!”

“I’m at my boyfriend’s show,” she says. She’s released August to return her attention to the plastic cup in her hand. Even two feet away, August smells pure vodka.

“Oh shit, Winfield’s performing tonight?”

“Yes,” she says. Someone brushes too close, threatening to spill her drink, and she throws an elbow out hard without missing a beat.

“When’s he up?”

The song switches to “Big Ole Freak,” and the cheer that goes up is so loud, Lucie has to lean in when she yells, “Second to last! Show starts soon!”

“Yeah, I gotta go! See you later, though! Have fun! You look really pretty!”

She pinches down a smile. “I know!”

August’s friends have elbowed their way right up to the edge of the stage, and the wave of bodies eddies her to them as the lights go down and the cheers go up.

The curtains look ancient and a little moth-eaten, but they shimmer when the first queen throws them open and strides out into the spotlight. She’s tiny but towering on eight-inch platform boots, wrapped in skintight green leather and sporting a pastel green wig laced with ivy.

“Hello, hello, good evening, Delilah’s!” she shouts into the mic, waving at the roaring audience. “My name is Mary Poppers, and I am here tonight representing Arbor Day, make some noise for the trees!” The crowd cheers louder. “Yes, that’s right, thank you, our planet is dying! But we are living tonight, darlings, because it is Christmas in July and these queens are ready to stuff your stockings, light your menorahs, hide your eggs, trick your treats, and do whatever the fuck it is that people do for Labor Day. Are you ready, Brooklyn?”

It starts off fast and keeps going—a “Party in the U.S.A.,” a queen named Marie Antwatnette doing a Bastille Day–themed voguing routine to “Lady Marmalade” that ends in frisbeeing French macarons into the crowd. Another queen comes out full-on New Year’s Baby in a rhinestoned diaper and sash and brings the house down with “Always Be My Baby” and some well-timed sparklers.

Second to last in the lineup is a queen introduced as Bomb Bumboclaat, and she stomps out in thigh-high boots, a saxophone thrown around her neck, and a red fur-trimmed dress with a matching cape. Her beard shimmers with silver glitter.

It’s not until the memory of Winfield’s one-man-band business cards swims into focus that August realizes who it is, and she screams on impulse as the number starts up—that ridiculous live Springsteen version of “Santa Claus is Coming to Town.”

“Hey, band!” Bomb Bumboclaat lip-syncs in Bruce Springsteen’s voice.

Mary Poppers sticks her head back out from the curtain. “Yeah! Hey, babe!”

“You guys know what time of year it is?”

“Yeah!”

“What time, huh? What?”

This time, the crowd shouts: “Christmastime!”

She puts her hand up to her ear dramatically. “What?”

“Christmastime!”

“Oh, Christmastime!”

Bomb Bumboclaat is pure comedy, all subtle hand gestures that have everyone screaming with laughter and throwing bills onstage and movements of her face that look impossible. She’s the first one to do a Christmas number at Christmas in July, and the crowd has been waiting. When she absolutely shreds the saxophone solo, the rafters shake.

By the time she’s done, the stage is littered in ones, fives, tens, twenties. Mary Poppers comes out with a push broom to get it all off the stage before the next number.

“Delilah’s! You’ve been amazing. We got one more for ya. Y’all ready to witness a legend?” Everyone screams. Myla snaps her fingers in the air. “Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome to the stage, just what the doctor ordered—Annie Depressant!”

The curtains fly apart, and there’s Annie in her signature pink—pink Lucite platform heels, pink thigh highs topped with red bows, pastel pink hair cascading down the front of her pink chiffon robe and pinned up on one side with a glittering, heart-shaped fascinator. She’s absolutely stunning.

She preens in the spotlight, soaking in the screams and claps and finger snaps, flourishing her rose-colored latex gloves through the air. She’s never seemed anything but confident since August first watched her sip a milkshake at Billy’s, but seeing her on stage, hearing the way the crowd shrieks itself hoarse for her, August thinks about what Annie said about being the pride of Brooklyn. It wasn’t quite the joke she played it off as.

The music starts welling up with soft strings and twinkly synth triangle, a few drum beats, and then Annie snaps her eyes forward to the crowd and mouths, “Give it to me.”

It’s “Candy” by Mandy Moore, and the crowd has about one second to react before she throws her robe off to reveal a bra and miniskirt made entirely out of candy hearts.

“Oh my God,” Wes says, lost in the wail of the crowd.

Annie winks and launches into her routine, writhing down the catwalk that splits the audience, leaning in to drag her gloved finger down the length of an awestruck guy’s jaw on begging you to come out and play. August has always seen Annie and Isaiah as two sides of the same person, but the way she soaks in the light, the way her eyes drip honey—that’s a different person entirely from the accountant who moved August’s desk up six flights of stairs.

She spins gracefully back down the catwalk, beaming, glowing, burning at five hundred degrees—and the music drops out. Annie’s own dubbed voice comes in.

“Actually,” she says, “fuck this.”

In an instant, the stage lights switch to pink, and when Annie throws out her right hand, a flood of rain starts pouring down from the ceiling above the stage.

The music comes back funky and loud and ballsy—Chaka Khan this time, “Like Sugar”—and two things become clear very quickly. The first, as water splatters from the stage and into their drinks: this is why Isaiah suggested they might need ponchos. The second: Annie made her outfit out of something that dissolves in water.

Within the first thirty seconds, her miniskirt and bra have melted, and with a twirl, she whips the last sugary wisps across the stage, leaving behind ornate red latex lingerie. Backup dancers come sashaying out from backstage and hoist her onto their shoulders, spinning her under the falling water, the crowd damp and transported and screaming themselves hoarse. August grew up a short drive from Bourbon Street, but she has never, ever seen anything quite like this.

She thinks of the last text Jane sent: a picture of fireworks from the Manhattan Bridge, Give the queens my love.

It’s hazy, but she remembers Jane telling her about drag shows she used to go to in the ’70s, the balls, how queens would go hungry for weeks to buy gowns, the shimmering nightclubs that sometimes felt like the only safe places. She lets Jane’s memories transpose over here, now, like double-exposed film, two different generations of messy, loud, brave and scared and brave again people stomping their feet and waving hands with bitten nails, all the things they share and all the things they don’t, the things she has that people like Jane smashed windows and spat blood for.

Annie twirls across the stage, and August can’t stop thinking how much Jane would love to be here. Jane deserves to be here. She deserves to see it, to feel the bass in her chest and know it’s the result of her work, to have a beer in her hand and a twenty between her teeth. She’d be free, lit up by stage lights, dug up from underground and dancing until she can’t breathe, loving it. Living.

Jane would love this.

Jane would love this.It keeps coming back and back and back, Jane tossing her head and laughing up at the disco ball, pulling August into a dark corner and kissing her dizzy. She’d love this, specifically, slotted right into place in August’s family of moody misfits, tucked against August’s side.

The second August lets herself really picture it is the second she can’t pretend any longer—she wants Jane to stay.

She wants to solve the case and get Jane out from underground because she wants Jane to stay here with her.

She’d promised herself—she’d promised Jane—she was doing this to get Jane back where she belonged. But it’s as blazing and unforgiving as the spotlight on the stage, nothing left in August’s sloshy drunk brain to hold it back. She wants to keep Jane. She wants to take her home and buy her a new record collection and wake up next to her every stupid morning. She wants Jane here in full-on, split-the-pizza-bill-five-ways, new-toothbrush-holder, violate-the-terms-of-the-lease permanence.

And not a single part of her is prepared to handle any other outcome.

She turns to her right, and Wes is standing there watching the show, mouth agape. The grip on his cup has gone slack, and his drink is slowly dribbling down the front of his shirt.

August gets it. He’s in love. August is in love too.

Fullepub

Fullepub