Chapter 1

May 1820

London, England

As one of the most dissolute rakes in all of London, Evander Beauclerk was game to try almost anything. But today, he was doing something he absolutely never did.

Going over the ledgers of his father's insurance business.

This was a mark of how deeply he was dreading the conversation he was about to have with his father. He would do anything to distract himself.

Slouching in a leather wingchair in his father's study, Vander frowned as he scratched out the total in yet another column. He hated this sort of drudgework, and considering his father had insisted upon meeting at the ungodly hour of half-nine, he'd managed only three hours of sleep. Combined with the fact that his head was still pounding from the impressive volume of brandy he'd consumed the previous night, he wasn't adding up the numbers as effortlessly as he usually would.

But it was a good thing someone was double-checking these figures. It had never occurred to him that his father, from whom he had inherited his considerable mathematical acumen, would lose a step in his middle age. But judging by the fact that he had bungled the calculation in six out of the eight columns, it appeared the old man's mind was a shadow of its former glory.

The door swung open, and his father minced into the room with the tiny, precise stride Vander could have picked out from a mile away. Cedric Beauclerk pushed his spectacles up onto the bridge of his nose as he peered at his son. "Evander. Good, you're here."

Vander bit back a groan. His father was the only one who called him Evander. He was Vander to his friends, Beauclerk to most everyone else, and Mister Beauclerk in polite company… not that Vander found himself in polite company on anything resembling a regular basis.

It wasn't that Vander disliked his full name; it was more the way his father said it. He always managed to emphasize the first syllable, "EEE-Vander," in a way that made Vander feel like he was twelve years old and about to receive a paddling from the headmaster.

His father took his time arranging the file folder he'd brought with him on the oversized mahogany desk, then finally turned to his son.

"So. Evander. I imagine you know why I summoned you today."

Vander had a fair notion but wasn't about to admit as much. "You'll have to enlighten me."

Giving a pinched frown, his father opened the file folder. He withdrew a single page of newsprint, turned it to face Vander, and slid it across the desk. "Care to explain this?"

Vander peered at the gossip column:

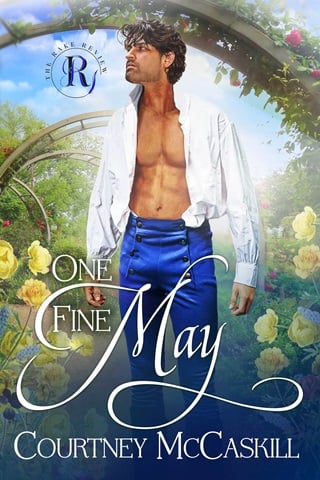

The Rake Review

By The Brazen Belle

May 1, 1820

Dearest reader,

Rough winds may shake the darling buds of May, whose blooms, many a poet has observed, are all too fleeting.

Not so the rakes of London, who are boundless in their multitudes. This month, as always, your diligent Belle has sifted through this interminable supply, and found a rake who has risen above his fellows:

Mr. E— B—

It is fortunate that the posterior view of Mr. E—B— is so exceptionally fine because that is the vantage point from which a woman is most likely to see him: walking away. Why, in the last six months, he has taken up and promptly discarded eight different lovers, and not the sort of women who are accustomed to being cast aside. It seems that even London's most sought-after courtesans are incapable of holding his interest for more than a fortnight. Perhaps it came as some consolation that, as the scion of one of the wealthiest families in England, he has left some truly spectacular parting gifts in his wake. Although the opera singer your faithful columnist was able to interview was disconsolate to have had the pleasure of Mr. E—B—'s company for only one night, the pleasure of his company in this case not being a mere platitude.

Although he is the worst kind of scoundrel, Mr. E—B— is not without his virtues. During his latest turn in the boxing ring, no fewer than six ladies swooned, but not due to the bloody and violent nature of the sport. No, they were overcome in the moment Mr. E—B— removed his shirt. Thanks to the successful shipping insurance company founded by his father, he is absurdly wealthy. And Mr. E—B— apparently inherited his father's considerable mathematical acumen, as my investigation revealed that he achieved the rank of third wrangler while at Cambridge! Why this accomplishment is not better known remains a mystery.

Still, the man is more slippery than an eel rubbed with lard, and for all his brains, has the attention span of a gnat. Given his inability to apply himself to anything for more than a fortnight, he seems likely to run his father's business into the ground. And, given the number of lovers he has taken in the last year alone, one trembles to think how many varieties of the pox he might be harboring at the tender age of eight and twenty.

In short, should you see Mr. E—B— around town, I must advise you to take this notorious rakehell as your model and walk away. Although I know the ladies of London will not heed my warning. How is it possible that every rake I have featured thus far has found himself caught in the parson's mousetrap? Will Mr. E—B— suffer the same fate?

I suppose we will soon find out. Until next month, I remain Brazenly Yours,

The Belle

When Vander looked up, his father's cheeks had gone ruddy. "Did you know about this?"

Of course, Vander had known about it. Ever since the first Rake Review column appeared in January, it was all anyone could talk about. Given Vander's reputation for being a scoundrel amongst scoundrels, his friends had placed bets back in January about which month Vander would be featured.

Charlie Dingwell had been the one to put his hundred pounds on May. Vander was going to make Charlie stand him a drink. It seemed like the least he could do.

Still, Vander wasn't about to admit culpability to his father. The columnist's use of initials offered him a sliver of plausible deniability.

He made sure his face was very neutral as he replied, "Of course. Everyone reads the Rake Review. What about it?"

His father leaned forward, narrowing his eyes. "And does this month's subject not feel slightly… familiar?"

Vander shrugged. "I don't believe it's anyone in my circle of friends."

"Do you take me for a fool, Evander?" his father snapped. "How many twenty-eight-year-old third wranglers with the initials E.B. could there possibly be?"

Shit. His father likely had him there. Still, he wasn't quite ready to admit defeat.

Vander made his eyes wide, and, he hoped, innocent. "Surely you're not suggesting that I am the subject?"

His father jerked open one of his desk drawers. "I cannot tell you how fervently I prayed there might be someone else to whom it could refer." He pulled a booklet from the drawer and slapped it down on the desk.

Vander peered at the title. The Cambridge University Calendar. He wondered if his father had gone out and purchased the latest edition, or if he subscribed to it every year for the pleasure of turning to the list of award winners from the year 1783 and seeing the words Senior Wrangler next to his own name, signifying that he had been the top student in mathematics from all of Cambridge's colleges in the year he took his degree.

His father jabbed a finger against the booklet. "But I have checked the list, and there is only one third wrangler with the initials E.B. You!" He glared daggers at Vander from behind his spectacles. "This is awful!"

"It really is," Vander said, dropping his pretense of innocence. "This Brazen Belle woman said I have the pox. I don't have the pox! I always use a sheath."

His father pinched the bridge of his nose. "A cold comfort, at best, when now the whole world knows my son has slept with eight women in the past six months."

Vander brushed this off with a flick of his wrist. "Eight women. That sounds"—about right, his brain supplied, but he obviously couldn't say that, so he went with—"exaggerated. Who are these eight women, I should like to know?"

His father pulled a handwritten list from that irritating file folder of his. "According to the private investigator I hired to confirm whether or not the lurid details in this column were factual, they include the widow Mary Louise Huntley, the actress Marguerite Cadieux…"

Vander's attention drifted as his father listed off the names. How like his father to have hired a private investigator to make sure he had the upper hand. Who cared how many women Vander had slept with? Society didn't even blink if married men kept mistresses, much less a young, unencumbered man such as himself.

"… and Eliza Mernock, who is"—his father paused, squinting at the list as if he could not believe his eyes—"a contortionist."

"They included Eliza on there?" Vander said, outraged. "That's just low. I scarcely even slept with her."

His father placed the list back in the folder, then slapped the cover closed. "I hope you appreciate what a disaster this is!"

"Oh, I do. In addition to claiming I had the pox, that Brazen Belle woman had the gall to print that I was third wrangler!"

His father stiffened. "And what, I should like to know, is wrong with that?"

Vander rolled his eyes. He should never have acquiesced to his father's demand that he sit for the Tripos exam during his final year at Cambridge. Vander was always so, so careful to maintain his image as a devil-may-care Corinthian. Attending lectures was the least fashionable thing one could do at university, and so he hadn't done it, not even once.

But the truth was… he did find mathematics interesting, so in his spare time, he had read the various mathematical texts assigned by his tutors. And the one and only thing he had in common with his father was a brain that absorbed mathematics like a sponge.

Everyone had been shocked when Vander, described by his tutor as a "non-reading" man, had posted the best result on the written portion of the Tripos exam. There were whispered accusations that he must have cheated. The problem was that he was the only one to have successfully solved most of the differential equations. Exactly whom was he supposed to have copied? When someone pointed out who his father was, the heads of house shrugged and placed Vander in the top group for the final portion of the exam, which consisted of a debate in Latin.

Because Vander had never applied himself in Latin, he had performed atrociously in the debate, finishing third out of his three-man group, much to his father's chagrin. To Vander, however, the real tragedy had been the dent this so-called "honor" had put in his reputation.

"What's wrong with it?" Vander huffed. "Do you know what Joseph Pickering called me yesterday? A quiz."

His father, who had probably been called a quiz every single day during his school years, and who no doubt considered it the highest possible compliment, stared at him blankly. "And this is a problem because…"

"I called him out," Vander snapped. "And I made it very clear that anyone who repeated the remark would have to face me, either at dawn or in the ring."

His father pinched the bridge of his nose. "That is another thing we need to discuss. I cannot fathom, Evander, why you would risk your mental acuity by getting bashed in the head in the name of ‘sport.'"

"I don't get bashed in the head." Vander ducked his chin and threw a few swift punches. "The best defense is a good offense. I get my opponent on his heels right from the bell and end the match in a matter of minutes. It's my signature."

His father's face was a portrait of skepticism. "So, you're saying that you never get hit in the head?"

"Hardly ever," Vander grumbled. He spun the ledger of figures he'd been correcting around to face his father and pushed it across the desk. "You seem awfully concerned about my waning mental capacity. It seems you should look to yourself."

His father winced, processing the columns in a single glance. "This is… atrocious," he agreed. "But I didn't do these figures."

"Who did?" Vander asked, surprised. His father had a strong aversion to delegating tasks. To be sure, running an insurance company, he had a dozen accountants on his payroll. But these, the overall numbers for the corporation, he trusted to no one but himself.

It was one of the reasons his father worked fourteen-hour days. Vander couldn't imagine how he did it. Fourteen hours of drudgery, locked in the dim little closet of an office he kept at the company's headquarters, every day for the rest of his life?

He would much prefer to get bashed in the head.

"I thought I would let Milton have a try at the account books," his father explained. "I see now that he was… not ready."

Vander grunted. Milton, who was Vander's first cousin on his father's side, was one year younger than Vander at twenty-seven. If Milton couldn't do basic bookkeeping by now, it didn't seem likely that he was ever going to improve, but it felt uncharitable to say as much.

Vander and Milton could not be more different in terms of temperament. They'd attended school together, and Milton wasn't a bad sort of chap. But whereas Vander had made a name for himself pulling legendary pranks with his best friend, David, Milton was a dyed-in-the-wool rule follower.

Milton probably would have been thrilled if someone had called him a quiz, but alas, the famous Beauclerk brains had passed him over. Vander couldn't help but feel a twinge of guilt that he had been the one to get them when he had so little use for them.

And, unlike Vander, Milton absolutely adored his father's insurance business, Beauclerk Marine Casualty, and had applied to work there as soon as he completed his education.

His father narrowed his eyes at Vander. "Returning to the matter at hand—this column is a disaster!"

Vander rolled his eyes. "It'll blow over. Come June there will be a new rake-of-the-month for people to titter over. Everyone will be talking about whether he will get caught in the parson's mousetrap, as the first four rakes did, and I will be forgotten."

There was something steely in his father's gaze that Vander didn't care for. "As the first five rakes did, you mean."

Vander snorted. "Not like the first five. I'm number five, remember? And I have no intention of being caught."

His father's nostrils flared as if this short, mousy man was going to breathe fire. "Oh, yes, you do. You are going to start leading a respectable life, and that includes marrying a respectable woman, and you are going to do it before month's end." His father leaned forward over the desk, eyes boring into Vander's. "Or I am going to leave Beauclerk Marine Casualty to your cousin Milton."

Fullepub

Fullepub