One

From:[email protected]

Dear Cas,

I saw the most pretentious film tonight. You’d have loved it. Everyone died, and the score was beautiful. Exactly the kind of thing you’d love. You know, whenever I watch a film where the score is beautiful, I think of you. I think of that night in your bedroom when I made you watch Gladiator for the first time and you cried. I think that’s the first time I thought you might have a heart. I still think about that night now, now that I know you don’t.

I’ve grown to think that the only good thing about you not having a heart is that it means you can’t love him either. That you don’t. Despite what I see on your social media.

Yes, I still check it every day – sometimes more than that. Sometimes I think you know I do, and you post stuff there just for me.

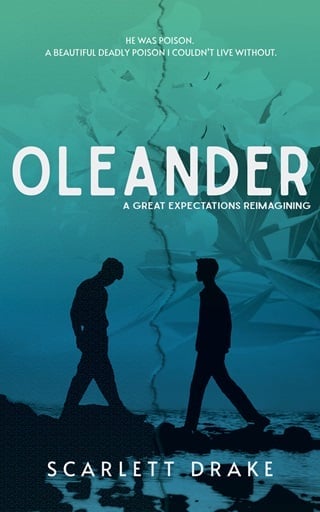

Secret messages you mean only for me (the heart you drew in the snow a few months ago. The close-up of the Oleander plant at Kew Gardens – I hope you didn’t eat it. The New York City Library) but then I wonder why you’d post the others: Pictures of him, mainly. Pictures of the two of you? Two glasses of red wine on a coffee table next to a set of keys to your new apartment. Are you happy?

You probably think I should have moved on by now. Maybe I should have. But don’t they say that the things that happen to us in the years when our brains are still developing become part of us forever? You happened to me. I grew around you. Then you left. You uprooted yourself, and now the place you grew out is just barren.

But there’s still a Caspien-shaped avulsion where you once were.

I’m writing fewer of these, which I guess is a good thing. They were the only thing keeping me alive after you left. Thousands of words that you’ll never read, each one a kiss I wish I could place somewhere on your body. I still miss you so much that it hurts, but every day, it hurts a little less. Every day, I heal a little more.

Anyway, I’m going to keep this one short. I really only wanted to tell you about the film. It was called ‘Tidvattensv?ngen’ – The Turn of Tides. It was directed by the guy who did the film about thedogsin the war.

Love,

Jude

I look back on that first year without him, and then my first few months at Oxford, as some of the bleakest of my twenty-eight years. I’d lost my parents when I was eight, and with it the sorts of experiences that most of us are guaranteed at birth; proud smiles at graduation, a tearful speech at a wedding, a hundred varieties of ‘I’m proud of you, son’ moments, a hundred thousand tight hugs from my mum. The kind of bottomless supply of positive reinforcement you can only get from the two people on earth who are programmed to love you unconditionally. And yet, it was those months after Caspien left me that devastated me most.

More than losing my parents. More than understanding what it meant to be an orphan, I felt the absence of him. The great chasm into which my hopes and dreams of a life with him had crashed and disappeared.

I couldn’t remember who I’d been before him, and didn’t know who I was now that he’d discarded me.

I felt more singularly alone than I had in my life.

Even now, there’s a physical reaction in my body when I recall the number of nights I spent crying and begging some higher power to have him come back to me; something between mortification and grief. And had some terrible god appeared before me in those months after he left, and given me the option of having my parents – either or both – back or Caspien, then I’d have said his name without a heartbeat’s hesitation.

I moved into Ellis Hall on September 18th, a year and four months to the day after he left me.

A week or so after my A-Level results had come in, a thick white envelope had arrived from the Oxford Admissions Board telling me I’d been accepted. I’d been dizzy from shock. I’d already paid a deposit on my student accommodation in Warwick; I’d already registered my car insurance to the address there. I’d researched the nearest library, Tesco, and parking to where I’d be staying. But here it was, an invitation to study at my first choice uni in black and white and with a tone of importance that reminded me of Caspien.

Caspien, who wouldn’t be studying at Oxford. Caspien, who was now in his second year of study at one of the world’s foremost musical schools.

I thought of turning it down, thinking of the work it would be to unpick everything I’d already laid down in Warwick, but I knew I’d look back and regret it. After all, surely it was better he wasn’t going to be there. That way, I wouldn’t have to see him across a dining hall or bump into him in a corridor or bar. I couldn’t watch him laugh and exist without me.

It was better.

In the end, it took me an afternoon of online admin to reroute my future an hour’s drive south. I didn’t expect there to be any chance of getting a place in the halls, given my late acceptance, but it so happened that a room in Ellis had opened up due to some last-minute refusals. But it would only be for the first academic year. I’d need to reapply for accommodation in year two – if I didn’t get one, then I’d have to find a house share or rent my own place. This wouldn’t be an issue, given that the monthly allowance from the trust fund would easily cover both.

Ellis Hall was an ancient brick building that looked and smelled like an old hospital. My room was south-facing with a single sash window, a single bed, and the single most depressing view I had ever seen. It was of the car park of a mini-supermarket and a row of large commercial bins. The worst part about it wasn’t even the view; it was that the bins were emptied on a Sunday morning right outside the window.

My floor, the second, was mixed; boys and girls, single, double, triple and quad, and with a large communal kitchen and a smaller sitting room. My single room had a small toilet and basin only. Bathrooms and showers were down the hall. Single rooms were apparently like gold dust here and I was shot envious glances as I’d carried my boxes and bags into it a few days before the start of term.

I met Bastian at Freshers Week. He lived on the floor below mine and had come upstairs looking for teaspoons one lunchtime. He was tall, lean, and angular with the longest legs I’d ever seen. He was from Noordwijk in the Netherlands, and struck up a conversation with me about toast toppings. He cycled semi-professionally and wanted to go full pro, but was studying medicine at Oxford as a backup.

He spoke English fluently and came over as sharp and witty, with a way of appearing completely absorbed in whatever you had to say. I liked him instantly. Bast – as he insisted I call him after ten minutes – was single but had left his high school sweetheart called Emmeline back in Noordwijk. A mutual decision, apparently. One that he didn’t seem to be crying himself to sleep over.

“What about you? Single? In love? Celibate?” He had come over to my room one night about a week after we’d met in the kitchen. We had bought some beer from the supermarket outside my window and were drinking it on the floor by the small electric fire as we listened to the university radio broadcast. They were playing Coldplay.

“I think technically I’m all three,” I said without any humour.

“Ah,” he nodded, knowingly. “What was her name?”

There was a decision to be made suddenly. Did I want to answer questions about my sexuality that I was certain I didn’t fully understand myself? Did I want to make a friend? Honesty was the first part of that, surely.

“His name was Cas,” I heard myself saying. “Caspien.”

Bast’s eyes went fractionally wider. I took this to mean I didn’t look like someone who was into guys. But he nodded and lifted his beer.

“So it wasn’t mutual?” he asked, clearly curious.

I shook my head. He nodded again.

“So, are you into guys? Girls? Both?” he asked. I shrugged noncommittally. “Nikita is hot.” Nikita was Russian, from St Petersburg, and shared a quad with Bast and two other guys. He was short, muscular and dark-haired; he was decidedly not my type. “And he is...” He made a gesture with his hand toward his dick and widened his eyes.

I laughed.

“You look at your roommate’s dick?” I questioned.

“He is always naked. I have no choice. I think maybe it’s a Russian thing, but maybe not. What about Conn? From the third. He’s gay and cute?”

“I don’t know who that is.”

“You do: Irish or Scottish, wears the Harry Potter glasses and is always carrying a book. He came down to borrow milk from the kitchen the other day.” Bast explained excitedly. “I saw him looking at you.”

“You’re so full of shit.” I shook my head. Conn sounded more my type than Nikita, though. If I had a type. I wasn’t sure that I did. Or rather, I had a very specific, very singular type. Boys who can’t love you and break your heart for sport.

“I’m not looking,” I said and drained the last of my beer.

“No one’s saying you have to fall in love, my friend, but you can have some fun, right? You’re young, good-looking, and studying at Oxford. Why else are we here if not to live our best lives?”

“Get a degree from one of the best universities in the world? Solidify our future?”

He made a noise of disagreement. “That’s for third-year Jude and Bast to worry about. Now, we live.” I knew part of his approach was that this really wasn’t what he wanted to do. He wanted to compete in the Tour de France. He had a poster of Eddie Merckx on his wall and considered cycling the most gruelling circuits on planet earth for a living his ‘dream career.’ It just so happened he was a brilliant academic, too.

He handed me another beer and stood up to change the radio to something more lively.

My eighteenth birthday arrived on a dark and cold Sunday. (My seventeenth hadn’t been much better.)

I woke up hungover. There’d been a party in one of the girls’ rooms on the third floor the night before. Booze lined up along a picnic table like a toxic pick-and-mix. I threw up into a sink. Smoked my first joint. Endured a blonde girl from Merton talking my ear off about her boyfriend back in Cardiff and how she suspected he was cheating on her, and how she wanted to get back at him. It shouldn’t have been a surprise then when she threw her leg over me and climbed onto my lap to kiss me. She tasted of wine and cigarettes, and I’d never been less into anything in my life. I’d gently guided her off and stood, stumbling downstairs to my room before passing out.

When I checked my phone, there were a few missed calls and texts. Luke, Beth, Gideon, and even one from Alfie.

I called Luke back when I’d showered, eaten some toast, and drank a litre of water. My head felt like cotton wool, and the low hum of nausea was thinking about following through.

“Judeyyyyy, happy birthday, mate! You’re an adult, congratulations!” Luke chirped. The sound of his voice settled some of the melancholy inside me, made worse by the hangover.

“Yeah, feels great,” I groaned.

“Partying hard, were we?” He chuffed in faux disapproval. “Hangovers only get worse from here on out, buddy. Ha, remember how shit you felt after a single glass of champagne at Cas’s birthday?”

I hadn’t prepared myself to hear his name, and the sound of it spoken so casually stunned me a little.

“Mhm,” I managed.

“So, what are your plans today? Anything nice?”

I hadn’t told any of the others it was my birthday. I was certain they’d want to take me drinking again. Though at that point, I was starting to wonder if it might be the only thing that would help.

“Not sure, maybe I’ll head down the pub later. Order my first legal drink.”

“Brave lad, oh wait, here’s Beth wanting a word.” My sister came on to wish me happy birthday and tell me how proud Mum and Dad would have been of me. I wasn’t sure that was true; weak and lovesick and becoming far too dependent on alcohol. The pit of sadness widened inside me the second I hung up the phone, and I filled it with the only thing I could think of.

I texted the Ellis group chat to tell them they’d better not be too hungover because it was my eighteenth birthday today, and I wanted to get exceedingly pished again later.

Then, because I was some kind of pain enthusiast, I pulled up Cas’s Instagram. There was a video posted last night. He was playing piano in a large, bright apartment – their apartment my mind supplied – with views out over the city. He wore a white shirt too big for his frame (my mind told me, helpfully, that it was Blackwell’s) and a pair of loose check pyjama bottoms. He looked painfully beautiful. Painfully far away. Painfully not mine.

I cried for a half hour after.

I got more drunk that night than I’d ever been in my life and woke up beside a girl whose name I didn’t remember, guilty and ashamed. That same shame and guilt I was beginning to associate with sex.

It was the worst birthday I could remember.

It was the start of a pattern. I had lectures two and a half days out of five, and an afternoon of this was tutorials: smaller groups and a professor would meet in a room – normally, his or her office – and discuss rather than sit and be lectured at. I had two of these on a Thursday afternoon. One was Post-War European literature with a very stylish, very intelligent Greek woman called Professor Gerotzi. The other class was one I’d picked at random from the list but which turned out to be one of my favourites: film criticism run by the youngest professor Oxford had ever had. Mr. Alexander: a youngish, good-looking, American who’d won an Oscar for best original screenplay at twenty-four for a war film called ‘Butchers and Heroes’. He was a guest lecturer for the academic year, and I’d been lucky to get into his class by all accounts.

Our assignments for Alexander’s class involved mainly watching films. Some we’d have to watch online using the university’s access codes as they were often 1960s Bolivian things no one had ever heard of. Other times, we’d go together as a class to the local cinema and watch a showing of something popular and terrible.

On Thursday after tutorial, I’d meet Bast, Nikita and Irish Conn (who was straight as a flagpole and absolutely not interested in me) with a couple of the girls from 1st in the Lord Avery and get plastered, laugh, and try to fill the hole in my heart with cheap rosè wine.

It would work until I got back to the dorm, where morose and alone with my own thoughts, I’d have a wank to hazy thoughts of his mouth and tongue and the sounds he’d make when he came. After, I’d lie warm and sated for about three minutes until the bone-cold ache rushed in again, quick as a rising tide. Sometimes, I’d think about the scene in his bedroom I’d walked in on, a piercing pain in my gut so sharp it could take my breath away.

The best thing to do, I’d found, was to drink enough so that the moment my head touched the pillow, I’d sink into undreaming sleep.

I drank, and I forgot. And then I remembered, and then I drank again. It was a perfectly acceptable cycle for a student. Everyone went out drinking; no one thought anything of it if you got so drunk you couldn’t remember getting home.

Alcohol wasn’t perfect, it couldn’t keep him out of my head completely, but it came bloody close. And next to Bast and Nika and Irish Conn, alcohol became an understanding and consistent friend to me that first year.

It was easy to get out of going home to Jersey that first December. I had two papers due the first week back, (Bast and Conn were going home until after New Year but Nika was staying) and with Luke and Beth enjoying their new childless life again, they didn’t seem too fussed when I said I’d stay at school over Christmas.

I’d miss visiting with Gideon. He’d been a steady friend that first year, even if his little tokens about where they were and what they were doing pecked at my heart like carrion. But now that I was away from the place, the thought of going back there made me feel physically ill: like returning to the scene of some horrendous accident. Some place where a terrible trauma had been done to me.

I couldn’t face it: that long drive up to the house, the view of his bedroom window from mine, the library, the hut. No. I couldn’t do it.

I wondered how many months I could avoid going home. Right then, I started thinking of an excuse for Easter and summer.

Fullepub

Fullepub