Thirty

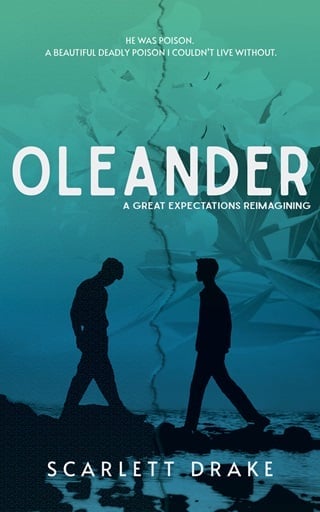

If I counted all the little ways he broke my heart, totalled them up, and set them on a scale, I doubt they would even come close to that first, deep break. The one that felt like a crack tearing through stone and earth, through things that had existed since the beginning of a life, to alter it irrevocably.

That was the thing about heartbreak – mine anyway – it didn’t feel like a complete shattering, like something that could never heal. It felt more like a deep fracture over which, in time, things could grow over. The tear could never be completely mended, not so that it was as it had been, but with enough work and time it could fool the eye into thinking there’d never been a crack there at all.

After, I spent a lot of time thinking about words Caspien himself had said to me the day he drew me in his mother’s bedroom. (The painting that hangs now inside the cupboard where I keep other things I don’t want to look at; the treadmill I used for three weeks after I turned twenty-five, the overpriced protein shakes I’d bought from an Instagram ad, my parents’ ashes.) The day he’d asked if I’d ever had my heart broken.

When I’d surprised him by answering yes.

He’d said, I think it’s easier for hearts to heal when they are still young.

He’d said nothing of the same heart being broken over and over again, sometimes in exactly the same place, sometimes slightly to the left, sometimes slightly above. That surely would weaken the entire structure until one day, the thing would crumble to dust.

But at the time, that first, deep break had felt like more than just a fracture. It was a great chasm cleaved through the heart of everything I believed; riven so deep and so devastating that I wasn’t sure anything could grow there again.

I remember the day vividly: fragrant, bright, and milk-warm. Like the earth was heating up slowly from within and by August it would be unbearable and broiling. I remember how I’d felt, too: joy, euphoria, hope. I was a bird flying far above the clouds on a clear blue day.

I just didn’t see the rifle pointing up at me from the ground.

I hadn’t contacted Moreland yet, despite it being almost a week since his visit, despite Beth and Luke hovering around me incessantly. Luke had a client who was a solicitor, and he’d asked him to look over the paperwork.

According to him, it was all above board and legal. Highly unusual, he said, stunned, but legal. His advice was to sign it immediately before whoever this insane person was changed their mind. He had a fax machine I could use. I’d shaken my head and said I wanted to think about it some more.

On Monday after school, I’d cycled straight up to the big house and burst in on Gideon in the red sitting room. (“Blue for business, red for repose,” he often said.) He was as I usually found him: reading, a glass of dark wine on the side table and wearing his gold-rimmed reading glasses. He closed the book on his knee and slid his glasses off.

“Jude. To what do I owe the pleasure?”

I held out the sheaf of paper to him.

“Is it you? Did you do this?”

He’d started with shock before sliding his body forward to perch on the end of the chair. He reached for the papers. Sliding his glasses back on, he began to scan the pages. I’d watched his face closely for clues for something that would give away the truth of it, but there’d been only a slight lift of his brow, which had disappeared a moment later.

Finally, he handed me back the papers, his gaze incalculable.

He said, “Well, that is quite something.”

“Well, is it? Are you the ‘anonymous benefactor’?”

He was perfectly still for a moment before he set his book aside and stood up.

“Perhaps it’s best not to poke at these things too hard; who knows what might fall out. Besides, you know what they say about curiosity. It seems to me like someone wants to see you do very well for yourself, Jude.” He pointed at the paper in my hand. “And has all but given you the means to do it.”

It wasn’t a denial. It wasn’t an answer. But it was all I got.

I had to assume that it was him and that he simply didn’t want Cas to know. But why? I couldn’t understand. Neither could I understand my hesitation to accept it. What was I waiting for? I knew the offer had no expiration date, but it still sat on my desk the entire week like a glowing treasure chest just waiting to be opened.

I wanted to speak to Caspien about it. But not over the phone. I wanted to show him the paperwork and have him pour scorn over it and tell me to burn it, or tell me I was the biggest idiot on earth not to have signed it yet.

He was due back that Thursday night; his last teaching day had been on Tuesday, but he had a Fence tournament on Wednesday evening that he had to stay at school for. He had to beat Hannes Meier in the final for a gilded replica of a trophy which was over 100 years old. I wished him luck and told him I’d see him on Friday night. Gideon was again in London (I remember wondering if he was meeting Blackwell again), so it meant we’d have the house to ourselves.

That Friday, Luke had a big contracting job on in Beaumont and couldn’t leave the site to pick me up, so that morning I’d taken the bike to school. The ride home had taken me around forty minutes, the last part quite heavily uphill, but I’d arrived home energised and sweating from the workout.

Caspien had arrived home late the night before; I’d seen the car come up the drive just after ten. Still, I’d waited a half hour before I’d texted to ask if he was in bed yet. I wanted to sneak out and go to the house to see him, and if he’d given me any indication it would have been welcome, then I would have. I missed him like an ache, a deep knot in my chest that I knew would only release when I saw him.

He hadn’t texted back until after midnight.

Caspien:

About to sleep. Come over tomorrow night.

Me:

did you beat him?

Caspien:

Yes. 15 to 11

I’d gone to bed with a proud smile on my face.

Since he’d told me to come over in the evening, I showered, made myself a sandwich, and tried reading a book for an hour or so. I was distracted, agitated, and excited to see him, my stomach and chest in complicated knots. That was the moment I realised, with startling clarity, how tightly my mood was linked to Caspien.

I thought about those months when he was cold and abrupt with me; how difficult I’d been. How unpleasant to Luke I’d been on those days he’d asked me to help out at the big house, specifically because I knew Caspien would be around and I hated being so small and insignificant to him. I thought of how lost and uncertain the world felt when he returned to Switzerland, leaving me alone to deal with feelings I couldn’t control or understand.

Then, the inverse: how every moment of wonder and pleasure and thrill I’d felt for the last few months had been because of him. Because I’d had him in ways I hadn’t even known I’d wanted.

I wasn’t sure it was normal or even healthy to be so completely wrapped up in another person – now I know it was neither—but I also couldn’t stop it, not least because it would mean a return to that feeling of before. For good or bad, I was tied, soul bound, to Caspien. It was terrifying and electrifying all at once. I was alive and in love, and the future we could have – that I would convince him we could have – stretched out before me, endless and shimmering.

I couldn’t wait to tell him about the golden ticket burning in my hand, about all the ways I was going to make him come this summer, about how I was going to be everything he needed and wanted. I couldn’t wait to tell him I loved him.

I was in love. And I was still young enough and na?ve enough to assume that was all I needed, to assume the power of that alone was enough to protect me from everything else.

But Cas had been right; I knew nothing of what love was supposed to be.

Unwilling to wait another minute to see him, I grabbed the trust paperwork from my desk and flew out of the house, convinced of my place in the world and Caspien’s place right next to me.

I’d thought about texting him first, but then I thought about his little gasp of surprise and the way his eyes would light up when I appeared, pushed him against whatever wall was closest, and kissed him. I thought about how easily he’d open for me when I dropped to my knees and fumbled with his belt. Of how he’d grow hard and desperate around my tongue, pleading with me even as he gripped my hair in his fist.

I ran faster.

When he wasn’t in the kitchen, I went straight to the library, and when he wasn’t there, I went to the music room. I went to the blue and the red sitting rooms next, though he rarely spent any time in either before deciding he must be sleeping. Cas liked to sleep in the afternoons; he’d curl up on the sofa or window seat in the library, close his eyes, and sleep as deeply as a cat.

The bedroom door had been closed.

I imagined sneaking inside and watching him asleep for a few moments before waking him. He looked different when he was asleep, the perfect symmetry of his features still and ethereal as water.

Whenever I watched him sleep, I wanted to be an artist like him. I’d taken some pictures of him on my phone, but I dreamt of being able to cast him against a page out of pencil or watercolour. The rosebud mouth and the delicate veined silk of his eyelids. Dark gold lashes against the arch of his cheekbones.

The bedroom door had been closed.

I snicked it open as quietly as I could. The smell hit me first. Sweet and pungent as death in the heat of the early summer. Heat which had already begun sinking into the walls of the old house.

It was the smell of heartbreak. The smell of dreams crashing down around me. The death of first love.

The bedroom door had been closed. And had it been open, maybe I wouldn’t have seen. I would have heard and understood, but I wouldn’t have seen.

I’d not registered the strange car in the courtyard outside. Expensive and grey and with a personalised registration, I would still be able to recite from memory even years later. I’d look for it everywhere for years to come.

I saw the elegant arch of Caspien’s back first, butter gold in the late afternoon sun.

A dark hand gripped his waist, firm enough to bruise.

“Don’t you dare come yet,” Caspien ordered, voice a taut desperate whisper. “I’ve waited too fucking long for this.”

“I missed you too, sweetheart...” A low breathy laugh.

I knew who it belonged to. That voice. That laugh. That hand. I knew, and I felt a gasping suffocating pain sear through my chest, a hole opening impossibly wide.

No.

No.

Please no.

“I missed this terribly,” Caspien panted, hips rolling.

“No,” I said. Not loudly, not loudly enough that they would hear me through that.

But he did. Caspien turned, looking at me over his shoulder. There was nothing in his eyes. No life. Nothing at all. But as our eyes held, I saw everything in them I would never have; hopes and dreams of a life shattering.

“Jude,” he said.

“What?” Blackwell said.

I staggered backwards out of the room, along the hall and down the stairs. At the foot of them, I fell, pain shooting through my knee. I ignored it. In the kitchen, Elspeth was taking off her coat, just arriving.

“Jude, sweetheart, are you hungry? There’s leftover—”

I bolted past without looking at her, past the stable and Falstaff, around the side of the house and on toward the trees on the other side of the estate. I don’t remember what thoughts were careening through my head as I ran. I remember only the noise in my ears and the pain in my chest, the burning in my legs.

The hut was the same as it always was: air warm and wood-soaked and close against my skin. I thought about the last time I’d been here. The last time he’d been here with me. He’d been colder, almost like he used to be.

I’d ignored it, pretended it was just his way of making going back to school a little easier. Christ, I was an idiot.

I’m not sure how long I sat there, curled up in one corner of that hut, fists clenched and tears rolling down my cheeks, but the light had begun to change outside. The refractions from the observation holes tilting lower and lower on the wood surfaces.

Then, I heard it.

The unmistakable sound of horse’s hooves. Then, soft, graceful footfalls picking their way across the long grass.

The door was pulled open.

Caspien appeared, draped in amber sunshine. My heart ached.

He wasn’t wearing his usual riding clothes, but a smart black shirt and a pair of light trousers, white trainers on his feet. He stepped inside and pulled the door closed behind him. He didn’t lock it.

There was nothing on his face to denote guilt or remorse; it was a beautiful mask. Doll-like and perfect.

“I guessed you would be here,” he said. “Though I went to the cottage first.”

I turned my head from him and tried, surreptitiously, to bring a hand up to rub the wetness from my cheeks.

“You were not supposed to see that,” he sighed. Then, as though he were irritated with me, “The plan was for you to come over this evening.”

I glared at him. “Oh, well, apologies for ruining your fucking plans! Sorry for missing you! Sorry for wanting to see you! Sorry for—” I cut myself off before saying it. Sorry for loving you. Instead I said, “Sorry for being a fucking idiot, I guess.”

He said nothing, but moved to sit on the bench seat opposite, graceful as a leopard. It wasn’t a large space, so when he sat our knees touched and I wondered if it was the last time I’d ever get to touch him.

“Jude, though it’s regrettable you had to see that, there are things you don’t understand.”

I felt my face rearrange itself. “Regrettable? Things I don’t understand?”

“I’m just saying that if you—”

“Do you love him?” I talked over him.

Caspien’s gaze sharpened. “You asked me that before, and I answered it before.”

“And I’m asking it again.”

“If I give a different answer this time, will it make you feel better or worse?”

I thought about that. If he said he loved him now, it would be far, far worse.

“Was all of it a lie?” I asked him instead. I loathed how desperate my voice sounded.

“Which parts?”

“The parts with me!” I roared so loud he startled slightly. “The things you made me believe, the ways you let me have you. I don’t understand how you could...” I shook my head. I couldn’t speak around the ball in my throat. It felt as though I was being choked from the inside out.

Then, a terrible realisation settled over me. I stared at him in horror.

“You never stopped, did you?” I said. “Seeing him. Blackwell was always there. You were just more careful about it. I was just more stupid about it.”

A glimmer of something in his eye told me I was right.

“And so, I was what? A way to pass the time? Did you talk about me with him? Laugh about me with him?”

He at least had the decency to look a little ashamed at this. Christ, the pain was blinding. I could barely draw my next breath.

“Why? Why even bother? You could have left me alone, left me out of it! Not made me care about you.”

This riled him. He sat up. “I never asked you to care for me, Jude,” he snapped. “And please, left you out of it? You wouldn’t let me. You threatened me! Threatened to tell the police. You acted like a child with no care of the damage you could do!” He calmed, looking me dead in the eye. “And then you found out his name.”

Everything stopped. The very air seeming to still.

“That was when it began...” I whispered, understanding everything all at once. “When you pulled me closer, when you wanted me the way I wanted you.” I looked at him, stunned. He’d never looked more cruel, more cold, more beautiful. “You’re fucking poison.”

Caspien’s gaze flickered with what looked like torment, but then he lifted his chin and stood. “If I am, then it’s perhaps for the best that I shan’t be around to infect you any further.” He reached for the door.

Panic fluttered behind my ribs. I stood. “What do you mean? Where are you going?”

“First, to France, then Sardinia, and after my birthday, we’ll settle in Massachusetts.”

There was a dreadful rushing noise in my ears. “But you’ll be going to Oxford. There’s the entrance exam and the interviews – you’ll have to be back for those.”

He stopped and turned, and for the first time, his gaze flicked to the pile of paper I’d dumped on the bench when I’d arrived.

“I’m not going to Oxford, Jude.”

“What?” I blinked. Not going? I didn’t understand. He’d always planned to go; his place was bought and paid for, and he’d told me that more times than I could remember. “What are you talking about, not going?”

“Oxford is your dream, Jude, not mine. I was never going.”

I shook my head. “No, you said—”

“I said it was where all Deverauxs went. That it was where Gideon went. That it’s where he expected I’d go.” Caspien’s voice had turned a little hard again. “But it’s never what I wanted.”

“Then where will you go?” There was a desolate edge to my voice.

“I’ll be studying at the Lervairè Conservatory of Music. In Boston. I was accepted last month.”

“No...you can’t...I can’t...” Then, I couldn’t imagine a life without him in it. Without seeing him, even if it were only that. Looking at him. Even if I couldn’t have him, I could still love him.

For him to live in another country for years was unthinkable.

I went to him then, urgently, humiliatingly, and I crowded him against the door and buried my face in his neck.

“Cas, no. Please don’t go. I don’t care about him, about what you’ve done. I can’t lose you, too. Just please, please don’t leave me.”

I felt him tense under me, warm body turning rigid. “Stop it,” he said in a tight voice. With great effort, because I was still crushed against him, he turned so that he was facing me. “I cannot love you; surely you know that.”

“I don’t care.” I could barely breathe. I was gasping, trying and failing to draw breath into my lungs.

“Maybe not now, but one day you will,” he said solemnly. “One day you’ll look back on this moment and hate me so much for it that you won’t be able to fucking look at me.”

I shook my head again, violently. “I wouldn’t ever. Cas, I love you...I love you...” I pressed my lips, tear-stained and trembling to his mouth, to his cheek, to his eyelids. “I love you so much, please. Please don’t go.”

He softened. Indulging me for a few moments. I even thought he kissed me back, but I think I imagined that brief softening of his mouth. Then he pushed at me, hard, and I stumbled back.

“Stop it.” He was trembling now, colour leached from him, and a touch of sweat beaded on his forehead. “This is finished now. I am going to Boston with Xavier. He is to start a new firm there, and we will live in the city, close to Lervairè. It is all arranged.” He was still talking when I felt the bile rise up in my throat without warning. I turned to empty it onto the floor of the hut.

“You don’t love him,” I said, wiping at my mouth. The words burned my throat.

“I don’t intend on loving anyone,” he said very earnestly. “And so it doesn’t matter where I am or with whom, as long as I am comfortable and far away from this place.”

Be with me then,I wanted to scream. But then I registered the word:

“Comfortable?”

“Comfortable, yes. Xavier has a great deal of money, and so I shall be able to live the sort of life I wish.”

“But you won’t be happy!” I spat it like a threat.

At this, he frowned a little as though thinking hard. “I am not sure I’ve ever been happy, Jude. So that shall make very little difference to me.” He pulled open the door.

“I could make you happy, Cas,” I managed, wiping at my eyes again. ”If you just gave me a chance, I think I could make you happy. I know I could.”

He stopped in the open doorway and turned back to face me. A sliver of sunlight was left in the hut, and it pierced through him at a downward angle like a bolt of holy light through his chest.

Once more, he lifted his chin, imperious as he met my eye. “You’ve always had rather grandiose ideas about what you can and can’t do. Oxford will beat that out of you, I’m sure.” He glanced once more at where the trust paperwork lay. “If you have a single ounce of sense in that bloody head of yours, then sign that.”

And then he was gone.

Fullepub

Fullepub