One

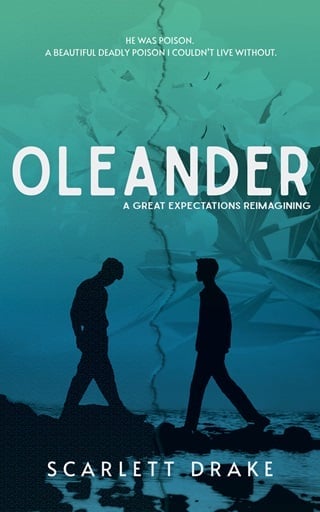

It was a bright, burning Tuesday in August when Caspien Deveraux broke my heart for the first time.

The news said it was the hottest day on record, though there have been hotter ones since. The weather map on TV showed red warnings, and there were reports of melting train tracks and things spontaneously combusting. My parents had been dead for seven years, and I could barely remember their faces.

It was hard to imagine there even was a time before. Before the Deveraux mansion and the two wraiths that haunted it. Before that summer, when everything was on fire, and I knew what it was to be consumed by flames.

But there was.

I hadexisted before.

I’d once dreamt dreams that were not about him – dreams that were not about his skin, his hands, or his lips which were always twisted with mockery and malice but which would, later, part with want and desire - though I could not now tell you what they were.

Dreams of my parents most likely. Of a life outside of the small island I’d called home since my parents’ deaths. Oxford, probably. Then London. On other, bolder days, Italy, New York.

The year I first met him, I was fifteen. School was done for the term, and the summer break stretched out before me like a cat in the sun.

It was a Tuesday. Life-changing things rarely happened on Tuesdays – or so I had thought. On weekdays, Beth left for work even before I got up; she had to drive to her sales job on the opposite side of the island, and since Luke made his own hours and I clearly couldn’t be allowed to stay home reading all day, I was told I was going to work with him.

He’d tried to make it sound like an adventure; uncaring that my adventures were inside the pages of the book I’d stayed up until 3 a.m. reading. They didn’t involve crumbling old houses and annual delphiniums.

Luke had been born with green fingers, he said. Once, when I was five, he’d said he’d been born with ‘green fingers,’ and I hadn’t known for a long time that he didn’t mean this literally. He knew more about plants and gardens than I knew about Terry Pratchett books. He knew more about plants than most of the garden experts on TV. He talked to plants. Covered them with blankets in the winter. Left the radio on in our greenhouse sometimes for the seedlings he was sprouting. Radio Four: because they liked voices more than music.

That morning, at the sound of him bellowing cheerily up the stairs (Luke never raised his voice in anger), I’d come downstairs, my eyes gritty and my bones still asleep. Yawning, I sat at the kitchen table while he set down a cup containing two boiled eggs, butter, salt and pepper. Buttery toast landed next to it a few moments later.

“Eat up; you’ll need your energy today,” he said around a mouthful of mushed-up egg.

I glared. “It’s child labour, you know.”

“Well, it’s not. Since I’m not paying you.” He thought this was funny and smiled wide. “Well, not in money anyway.”

They were buying me a new laptop the week before school if I stuck to this ‘arrangement’. My stomach flipped with excitement when I thought about it. I could write on it. I could write. Properly. The one I used now was about ten years old and struggled to load two web pages at the same time.

“Three days a week?” I checked.

He nodded. “Eight until three.”

“No Saturdays or Sundays?”

“Not a one. Not unless you want to. I’ll give you double for a Sunday, though.”

“Double of nothing is nothing.” I pointed out.

Luke’s eyebrows rose. “So you aren’t as bad at maths as Mrs Edmunds says, then? Interesting.”

I grumbled as I bit down on an edge of toast. It was still warm, and the butter dribbled over my lip, the scent of the peppery egg making my stomach growl. I’d been hungry before I’d fallen asleep last night.

“How late did you stay up?” His brown eyes softened.

I shrugged.

“Well, I’ll try and go easy on you today. Lots to do. First day on the job is always the most important.”

I shoved a spoonful of egg in my mouth and stifled a satisfied moan. I’d take his word for it.

Showered and dressed in my oldest pair of shorts and a ‘Green’s Gardening Group’ t-shirt a size too big, I flung my backpack into the footbed of Luke’s van first, before climbing in after it. The van was loaded up with spades and forks and an array of gardening tools I felt exhausted just looking at. Luke whistled, happy – excited even – about the prospect of reanimating the long-dead gardens of Deveraux House.

I pulled out my book as he drove, folding back the cover and losing myself between the pages while he sang along to the radio. It was a forty-minute drive out of Gorey to St. Ouen in the north-west.

Luke hadn’t stopped talking about this job for the last month. He’d won the contract over a larger firm in St. Aubin to resurrect the gardens of one of the oldest properties on the Channel Islands: Deveraux House. Built and owned by the Deveraux family, its current inhabitant was Lord Deveraux: by all accounts, some crazy old queen who was as mad as a box of wet cats. I didn’t know much about him, and I didn’t much care either, but he was a source of morbid curiosity for the island as far as I could tell.

That day though, Luke was happy. Excited like a kid on his way to a theme park. He wasn’t thinking of anything except what this contract could mean for him, Beth, and me.

Back then, they fought a lot about money. Or rather, Beth did. I assumed myself to be the cause of that. Me, a kid neither of them had asked for but had been obliged to take in. My parents – mine and Beth’s parents, I should say – had been hit from behind by a truck driver on their way home from a friend’s wedding, making us both orphans in the blink of an eye. Beth and Luke had been babysitting me that night. Mum and Dad were going to take me with them before Beth had offered – last minute, as I’d heard it told – to allow them a night out together. A night that had turned out to be their last night alive. A night I think now must have been filled with awful pop songs, terrible speeches, and mediocre food.

I think about that frequently. About what I’d want my last night on this earth to look like.

It would be us, of course. Caspien and me, someplace warm. A night spent with our limbs tangled together, nice food and wine in our full bellies as we took that other more intoxicating pleasure from each other.

But my parents had been at the wedding of a distant cousin. A ten-second lack of attention by an overtired truck driver and everyone’s lives had changed forever. My mum and dad became a story in the Honiton and Devon News, and Beth and I became orphans.

Ten seconds.

Beth had become a parent and an orphan at the same moment. Luke wasn’t a replacement for my own father, but it felt strange to call him my brother. And so ‘uncle’ seemed like some middle place that suited us both. I’d always been a little difficult as a child, moody and insular, and prone to bouts of deep self-pity. And now I wonder if Gideon and Caspien had smelled that on me. Like sharks in the water. My heart, a soft and fleshy thing that was vulnerable to their poison.

Over the years, that soft fleshy thing has hardened, broken, bruised and scarred over but pierce through the hard outer shell, and there it was. Unchanged at its core.

That day, we pulled up to the gates at Deveraux House before 8 a.m. Another Green’s van was already there, waiting. Luke got out and walked up to the gate, two rusted hunks of metal that looked as though they hadn’t been opened in years. I learned later that they hadn’t. Everyone left and arrived via the service gate on the other side of the estate.

Luke stood around for a bit, chatting with Harry and Ged, gesturing at the gates and looking through it. You couldn’t see the house from here. It was situated at the end of a long, twisting, tree-lined drive, which was a curtain of green at this time of the year. In the end, Luke pulled out his phone and made a call, the recipient presumably telling him to come around to the west side service entrance or simply pull open the gates. Luke decided on the latter. With some effort, he and Harry prised open the large gates before sprinting back to the vans and driving through, Ged getting out to pull them closed behind us.

With the window down, I leaned my head out and then my arm, snatching a handful of green as the leaves brushed the side of the van. The house flickered into view through a break in the trees as we drove, but the moment it was revealed in full, I sat bolt-upright in my seat and gaped at the thing. It was a behemoth of a building. A brownish-red brick mansion with over a hundred windows and a stone-covered wraparound veranda on one side, a large glass conservatory on the other, a turreted section, and around ten chimneys.

It sat slightly raised, as though on a dais of green, with acres of overgrown garden spilling out from its walls. In the heat of the day, it had an almost dream-like quality, a mirage in a desert. There was something unmistakably English in its architecture, something found nowhere else, but it was this same quality that made it distinctly sinister in the darker months. As though some screaming madwoman lingered in its upper rooms, wailing late into the night.

As it was, no women lived in Deveraux House and hadn’t done so for more than fifteen years. The full story of why would turn out to be tragic and fateful, and one I wouldn’t hear until the following summer.

Luke drove the van up to the front, slowing to get a look at the wide, arched entryway. The large double door was closed, so he followed the curve of the stone drive around the house towards the back into a small courtyard. The gravel under the van sounded extremely loud as we crunched around the building. We passed the glass-domed conservatory, dirty and unused, with overgrown weeds in a tumble behind the glass. A few even poked out through a few shattered panels.

Finally we pulled up on the northern side of the property. The courtyard was U-shaped, with a row of low buildings on one side and the house on the other. A single solitary figure stood by a door in the far corner of the courtyard.

“Wait here,” Luke said, giving me a nervous smile before climbing out of the van.

I nodded, happy to be able to stay outside of the thing – the place did not scream ‘visitors welcome.’ As Luke met with Harry and Ged at the back of the van, I glanced in the wing mirror to see that the figure standing by the door was a boy. I couldn’t see him properly from where I was, but I was certain he wasn’t any older than I was, maybe even a few years younger. Bright blonde hair to his shoulders like a girl, he wore khaki-coloured shorts and an oversized, short-sleeved shirt. He stood oddly still while waiting for my uncle as though he were guarding the place.

We were close enough that I heard him speak when Luke approached.

“You are the gardener,” the boy said in a very polite voice.

Luke stuck out his hand. “Luke Green.”

The boy didn’t shake it, and Luke dropped his hand. He gestured to Harry and Ged. “This is Ged Davis and Harry Foote. Um, is your dad home?”

“My uncle Gideon is inside. Follow me,” he announced before spinning on his heel and disappearing inside. Luke glanced at the others and shrugged before following him inside.

It was stifling in the van, even with the windows down, so I opened the door and turned my body sideways so my legs were outside. There was little shade to be found in the courtyard, but I spotted a sliver of shadow on the side near the row of low buildings, grabbed Terry Pratchett, and made my way towards it. I had no idea how long they might be in there talking about annuals, perennials, and pruning, and I wasn’t willing to sit in Luke’s metal sweatbox and wait for death. It was illegal to leave dogs in hot cars, so I supposed it was illegal to leave fifteen-year-olds in there too.

I sat down with my back against the wall and my knees pulled up and opened chapter five. I’d just started chapter six when I heard a soft crunch on the gravel. Expecting Luke, I raised my head from the book.

The blonde boy was walking across the courtyard toward the row of low buildings – toward me. He was no longer wearing slippers. He wore brown leather boots that stopped at his ankles, and white socks pulled up to his knees. I was half hidden between two brick columns, and so he didn’t see me at first, allowing me to observe him as he strode purposefully toward me.

The way he walked was strange. He didn’t walk the way boys usually walk. The way other boys ambled, dragged their feet, and scuffed their shoes, this boy walked as though each step was a considered movement. A careful motion of his limbs and body forward toward a very precise destination. He carried something under his arm that I couldn’t see. He was almost upon me when he finally sensed my presence, his eye catching me in its periphery.

He didn’t startle, not a single gesture that would indicate shock to find a boy curled up in a dark corner of his courtyard reading.

He stopped moving and turned to face me fully.

The shock that should have been his was mine.

A jolt hammered my chest as his eyes locked with my own. I couldn’t make out their colour from where I sat, the sunlight pouring over his shoulder, blinding me. All at once, it was the most important thing in the world. The colour of his eyes.

I rose to my feet quickly to face him, a rush of pleasure moving through me at the fact that I was taller. By quite a bit. Half a head, at least.

His eyes were a pale, ice blue.

“Who are you?” he asked in a sharper tone than he’d used with Luke. It somehow had the ability to sound both soft and hard as stone at the same time. “If you’re one of those gypsies here to beg again, we don’t have any work for you.” He drew his gaze down my body and back up, distaste evident.

My ears burned with embarrassment.

“I’m Jude.” I got out.

“I don’t care. Now leave. There’s no work for you here.”

My eyes nearly bugged out of my head. I wanted to hit him. Burst his stupid, weird nose. My cheeks felt hot, and my breath quickened from anger.

“Luke’s my uncle,” I said, breathless with anger. “I’m waiting for him.”

His pale eyes narrowed. “Who’s Luke?”

I frowned at him. Was he slow? He’d literally just met Luke. I glanced at the house.

“Oh,” he said. “The gardener.”

I nodded dumbly.

“Right. Well, fine.” He looked me up and down again. “You look like one of those begging gypsies.”

He turned away and walked to what I soon understood was a stable. A few minutes later, he emerged, leading a huge caramel-coloured horse by a strap across its mouth out into the bright August sunshine.

It was the first time I met Caspien Deveraux, and I loathed him with a passion I didn’t know I was capable of.

And though I didn’t know it then, I’d soon come to love him with the very same ferocity.

Fullepub

Fullepub