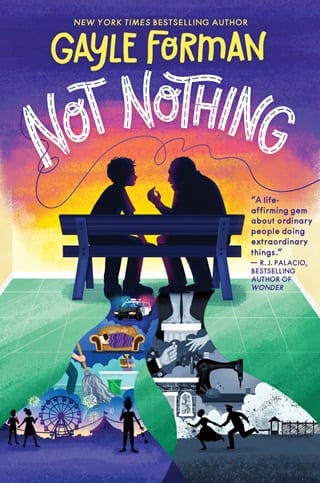

31. Not Nothing

NOT NOTHING

It is the first of September, the day our lives changed in 1939 and the day the boy's life will change one way or another. It is the day of his hearing.

He is standing on the courthouse steps, flanked by his aunt and his uncle, trying so very hard to be brave. He figures that if you could sneak into a concentration camp to help me (and countless others) escape, if Maya-Jade could be brave about having a mom with cancer, he can be brave about this.

Maya-Jade has been on his mind constantly since the fair. He wrote her an apology. This was the first of the three things I asked him to do: Make right to the people you've hurt.

So he wrote Maya-Jade a letter apologizing for what he'd done to Toby and for not telling her the truth about it. He wrote one to his aunt, apologizing for causing her so much trouble and costing her so much money. His aunt had replied with a gruff "Balderdash!" and turned away so Alex wouldn't see the tears in her eyes.

He also wrote a letter to Toby. But he understood that for Toby a letter was possibly too little. It might be that nothing in the world will make it right with Toby. And Alex will have to learn to live with that, to use that pain to do better in the future.

Because he will do better. He already has.

At the top of the courthouse steps, Frank joins Alex. In his hand is the boy's file, inside of which is the letter I dictated to Etta.

That was the second thing I asked him to do: Go find Etta and tell her to come to me immediately .

Alex had called Etta on Frank's phone. "Josey said you need to come immediately."

It was Monday evening, so Etta had been home watching TV, but she hauled herself upright, and without asking how the boy would know this or why he was calling from Frank's phone, she got in her car and came to me. She didn't need to be told that my time was running out. Of all people, Etta knew.

I asked her if she would write a letter that I would dictate. There was so much I wanted to say, about this troubled boy who landed in my room, who brought me back to you, but I was running out of breath, of time, of life, so I kept it brief. I told the judge all the good the boy had done since arriving here. All the love he had found here, in the Antechamber of Death, of all places. What the boy might do if only he had the—and I'm sorry to use the word because I know how much he hates it—opportunity.

When I was finished dictating, I asked Etta to let the boy stay on at Shady Glen.

"But," she began, "you know what he did."

"Yes," I replied. "But more important, I know what he will do. If he has the chance."

"I'm not sure I can," she said.

"I know, but you can try. It's the most any of us can do."

She paused. And I added the obvious. "Consider it my dying wish."

Tears filled her eyes. She kissed me on the forehead. And then, even though it was Monday night and she was supposed to be taking it easy, she sat by my bed and held my hand so I would not be alone.

But I was not alone. You were there in the room with me. Not the painting, but you. The painting was now with Alex. That was the third thing I asked him to do: Take Olka home with you.

He didn't want to. "But she's yours," he said.

"She's ours now," I replied.

The rest I did not say. That you had watched over me all these years, but soon we would be together again and I wouldn't need a painting. So I wanted the boy to have you when I was gone, for him to remember that people can and do change, for him to have someone to watch over him, to inspire him.

He seemed to understand. Because he gathered my frail body in his and hugged me until Frank told him it was time to go.

And it was. For both of us.

When you are truly ready, things move fast. I died an hour after I dictated my letter to Etta. She contacted the undertaker and called Adek's children, who were my next of kin, and then called Frank to tell him the news. "He wrote a letter of support for Alex before he went, and"—she paused here, feeling her baby kick with what felt like urgency—"if Maya-Jade and her family allow it, he can come back to work."

Three things never failed to shock the social worker: people's capacity for cruelty, their capacity for kindness, and their capacity for change. "Thank you," he said.

Etta said she would call Maya-Jade's parents and, with their permission, would put Frank in touch with Maya-Jade.

"Hi, Maya-Jade," the social worker said over the phone a few days later, after he'd spoken to Mim and Laura, who in turn had discussed it with Maya-Jade, who'd agreed to the phone call. "I don't think we've met, but I'm Frank. I'm a friend of Alex's."

At the boy's name, Maya-Jade's eyes filled with tears. Of course, they'd been full of tears nearly constantly since the fair, first because she'd found out her best friend was a terrible person and then because she'd found out that I'd died.

"I don't want to talk about him," she said.

"I completely understand. But if it's okay with you, I'd like to tell you a story about me."

"Whatever," she said.

"I'm not sure if you know this about me, because I don't advertise it, but I'm a trans man," he began. And then he told her about being a child in rural Ohio nearly half a century ago, when the world was different and also not different. He recounted some of the terrible things people had said and done to him, perhaps no one worse than his own father, who'd kicked him out of the house when he was sixteen and did not speak to him for fifteen years. Until one day out of the blue his father wrote him a letter, saying that he wanted to be better, promising that if Frank could forgive him, he'd spend the rest of his life making amends.

"And he did," Frank told Maya-Jade. "He called me every week and visited when my wife had each of our daughters. After my mom died, he moved closer so he could be around the girls, and after his first stroke, I moved him to Shady Glen. Right before he died, I asked him the question I'd wondered about since he'd reentered my life: ‘What changed?' He stayed quiet for so long I thought he was sleeping. But then he said, ‘I think you changed me. Sometimes a person just needs a reason is all.'?"

"Why are you telling me this?" Maya-Jade asked.

"I think Alex needed a reason to change. And you, and the people he met at Shady Glen, gave him that."

The tears that fell down Maya-Jade's already tearstained face were a different flavor from the previous ones. Those had been tears of anger (justified) and self-pity (ditto) and mourning (I was 107, totally unnecessary). These tears were the cleansing kind, the sort that pave the way for fresh starts, second chances, that allow a person to see ugly in the world and not look away, but to see beauty, too, the potential for love. The way I saw both in you when we first met. The way you saw both in me when we first met.

Not long after she hung up with Frank, the mail carrier arrived. Amid the bundle of catalogs and credit-card offers was Alex's apology.

And so now, on the first of September, Alex waits on the steps with his aunt Lisa and uncle Morris and Frank, trying to be brave. Maya-Jade, riding to the courthouse in the Shady Glen van alongside Julio, Leyla, Minna, and Sid, is also trying to be brave, though it's hard. She's tired—having stayed up half the night to edit the Operation Rise interviews to show the judge—and nervous. Her sweaty palms wet the speech in support of Alex that she plans to read to the judge—and to Alex.

The judge will watch the video. He will listen to Maya-Jade's trembling appeal, note the tears in her eyes and Alex's eyes as they look at each other. He will read another letter from Etta declaring that Alex can continue to do community service at Shady Glen and another from the boy's aunt and uncle, petitioning to remain his guardians. He will see Minna and Sid and Leyla and Julio sitting behind Alex, along with his aunt and uncle. He will read my letter, asking for Alex to be judged not for the worst thing he's done but for the better things he's done this summer, the best things he might yet do.

The judge will rule against sending Alex to a reform school. Instead he will continue living with his aunt Lisa and uncle Morris, who will, only a little begrudgingly, trade in the lumpy couch for a bed, over which your portrait will hang.

He will order Alex to do two more years of community service, which can be continued at Shady Glen. Maybe the judge thinks this is a punishment, but Alex recognizes it for what it is: an opportunity. And he will stay much longer than the two years, as he and Maya-Jade continue Operation Rise.

He's only twelve. He has so much time. It took me 107 years to rise to the occasion of my life by helping Alex rise to his. Maybe compared to what you did, Olka, it's not that much. But you know what, my love? It's not nothing.

Fullepub

Fullepub