All Shall Be Well

R owan, Willow and their father were partaking of afternoon tea when Niven arrived back from the docks. Rowan had to admit he was beginning to enjoy the taste of good food again, and there was nothing like a bracing cup of tea to help a man forget…Not that he would ever forget he had only one good leg. Still, perhaps he could adapt and make a life for himself. The future of the dukedom depended on it.

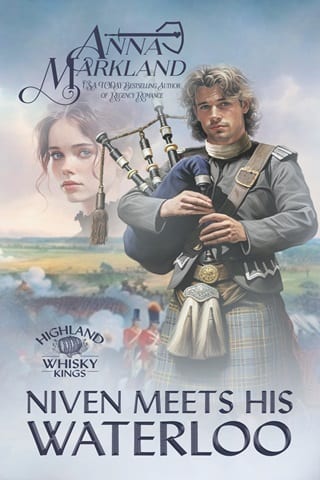

He was inexplicably pleased to see Niven had picked up his repaired bagpipes. His brother-in-law was correct that it was difficult to tell where the bag had been damaged. He and Niven had told and retold the story of the French soldier's bayonet, but Rowan couldn't resist telling it again.

Amid the chuckles, Rowan's father said, "Give us a tune, then."

Smiling, Niven tucked the bag under his arm, and cleared the mouthpiece.

But then, the color drained from his face. The blowpipe fell from his gaping mouth. He stood frozen like a stone statue.

Rowan understood completely. "Leave it for now, Niven. It will come back."

Niven's knees trembled. His throat was as dry as a desert. His mind failed to grasp why he couldn't remember how to play the bagpipes, something he'd done with natural ease since he was a bairn. The beloved pipes had kept him alive and sane in Flanders, but the prospect of hearing them wail again knotted his gut.

His broken heart knew the reason. The pibrochs would forever remind him of the horror.

Willow and her father sat in stunned silence. Thank the good Lord that Rowan understood. His intervention saved the day. "Maybe later," Niven lied. "I'm a bit out o' sorts after bidding farewell to Tavish."

"Of course," the duke replied. "How are things at the offices?"

Niven preferred not to mention the office clerks and dock workers had been thoroughly delighted to see him return. "Good," he replied noncommittally.

"Would you like some tea?" Willow asked, clearly puzzled by his behavior. "Or perhaps a sandwich?"

"Sounds good," he replied, filled with regret that he would never be able to explain his reluctance to play to the woman he loved. He could barely explain it to himself.

"A drop of Uachdaran with your tea?" his father-in-law suggested while Willow rang for freshly brewed tea and more sandwiches.

"Aye," Niven replied, though he doubted Dutch courage would solve the problem.

When Willow and Niven retired to their chamber to dress for dinner, she struggled with what to say. It was evident his reluctance to play had something to do with the war, but how to approach the matter? It was imperative he play again. The bagpipes were part of his heritage, an important part of him.

She decided patience was the way to go. He wouldn't thank her if she nagged him about it. "I understand," she said. "It may take a long while, but you'll play again. The bagpipes are in your blood."

"Aye," he replied sadly, drawing her into his arms. "Or mayhap I'll stick to the fiddle."

It was tempting to retort that his defeatist attitude sounded like Rowan, but she would never be so small-minded. Her brother was doing his best in the circumstances.

All in good time , she said to herself. It reminded her of a mantra written by Julian of Norwich, a medieval mystic her mother had been fond of quoting. All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.

Willow resolved from henceforth to make it her mantra.

A week later, Niven still hadn't plucked up the courage to take up the pipes. It played on his nerves and only worsened his insomnia. He and his father-in-law had arranged to go to the shipping offices today, so he let Willow sleep and came down for an early breakfast. Perhaps a day or two of hard work would rid him of his memories.

Rowan was the only person in the breakfast nook. "His Grace still abed?" he asked.

"He will be down shortly," Rowan replied. "I hoped you and I might have a word."

Niven wondered if Rowan had engineered this meeting so the two of them could talk—probably Rowan intended to give Niven advice on running the company.

"In Papa's study."

This was a surprise. Evidently, the word was to be something they had to discuss in private. "Now?"

"If you please."

Over the course of the past few days, Niven had noticed Rowan had managed to get to his feet without the help of a footman, so he made no move to assist his brother-in-law.

Rowan led the way to the study, clearly in full control of the crutches. The first thing Niven espied when he entered the room was his bagpipes sitting on the duke's desk. His gut twisted.

"Nay," he protested. "I canna."

"I've been telling myself the same thing since I lost my leg," Rowan replied, pouring two glasses of whisky. "I've decided never to say it again."

"I'm glad ye've come to terms wi' facing the future," Niven said honestly. "But…"

Rowan offered Niven a glass. " Uachdaran for the toast, of course."

"The toast?" Niven asked.

"Aye, laddie," Rowan quipped. "We're going to salute the thousands of men who weren't lucky enough to make it home from Waterloo. Cheers."

" Slàinte ," Niven echoed before they drained their glasses.

"Now," Rowan declared. "You are going to play those infernal bagpipes in tribute to those fallen heroes."

Niven shook his head.

"It's not a request, soldier, it's an order, and neither of us leaves this room until you play."

Niven realized he had no choice. If Rowan had come to terms with his loss, surely Niven King could overcome his reluctance to play the pipes. "Aye, Major," he replied. He strode to the desk, tucked the bag under his arm and tuned the instrument. He selected Peace and War , the pibroch Kenneth McKay had played outside the relative safety of the square.

His vision blurred as the pipes wailed.

Leaning on one crutch, Rowan saluted, his cheeks wet with tears.

As the last notes faded, the two men faced each other for long minutes. When Rowan saluted him, Niven realized he and Halstead shared a bond that would never be broken. They had lived through hell and survived to tell the tale. "I thank ye," he said.

"I wouldn't be here if you hadn't been so doggedly determined to keep me alive," Rowan replied. "This was my way of thanking you."

On her way downstairs, Willow heard the pipes. She hurried into the breakfast nook where she encountered her father. "He's playing," she exclaimed breathlessly. "Niven's playing his bagpipes."

"I heard," he replied. "Rowan decided to force him into it."

The ramifications of this statement were so overwhelming, she had to sit. It was just a first step for two men she loved, but it was progress. "All shall be well," she murmured.

"Your mother would be delighted you remembered her favorite mantra," her father replied wistfully.

FINIS

If you missed Tavish and Payton's stories, here's a peek at the covers and the links.

Anxious to know what happens to Rowan and Daisy? Here's an excerpt from THE THREE TREES.

St. George's Church, London, June 1816

"Do you take this man to be your lawfully wedded husband…"

The minister of St. George's droned on, but Daisy barely heard the rest of his preamble. Conscious of fidgeting among the large congregation seated in the pews behind her, she risked a glance at her fiancé. Reginald Fernsby was a very handsome earl, a gentleman who treated her well, but he wasn't Rowan Halstead.

How was her former fiancé coping on this first anniversary of Waterloo? The memories of his horrific ordeal must have come rushing back—if they'd ever left him, which she doubted. If only he'd realize she still loved him, would love him if he had no legs at all. He was the only man who'd seen and brought out her good qualities. With him she'd been a whole woman. But he'd thought to spare her marriage to a cripple. Foolish man.

The minister cleared his throat when Daisy didn't respond. Deafened by the thudding in her ears and suddenly feeling suffocated, she met Reginald's puzzled gaze. There was nothing for it but to embarrass him in front of the who's who of the London elite. "I'm sorry," she murmured. "I can't do this."

She thrust her bouquet at her maid of honor, surprised to see sympathy in Cat's eye's and not censure. As she stumbled blindly towards the endless aisle, she was grateful for her brother's arm. Kenneth appeared out of nowhere and escorted her past the gaping crowd. Once outside, he bundled her and the mile long train of the costly wedding gown into his ducal carriage.

Trembling, she expected a reprimand. He'd footed the bill for the entire wedding. Instead, he climbed in, sat beside her and said, "I hoped you wouldn't go through with it."

Fullepub

Fullepub