Visitors

N iven spent the longest week of his life trying without success to instill hope in Rowan's heart. He fretted about losing time when he could have been on his way home. The prospect of explaining to Willow that he'd left Rowan behind didn't sit well in his gut. It was ludicrous. He owed Rowan nothing but resentment. Yet, he couldn't abandon him. The war had robbed Rowan of his leg, but gone too was his bluster and self-confidence. Niven couldn't do anything about the lost leg but, for some perverse reason, he wanted to restore Rowan to his former bossy, opinionated self.

Ash and Thorne left with their regiment. Apparently, neither was given permission to say goodbye to his brother. It was left to Niven to inform Rowan of their departure.

"I don't fault them," he sighed. "Thorne will always wrongly blame himself for my injury and Ash is horrified he'll now inherit the title."

The Cameron Highlanders also left to march on Paris, but not before Kenneth McKay came to bid Niven farewell. Word of his heroics outside the square had apparently spread even to the hospital and he was cheered by the wounded officers. His visit not only brought light into a dark place, he modestly insisted it was Niven who'd kept him going through the worst of the battle.

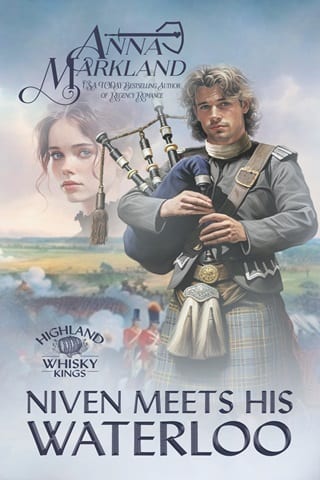

He played a rousing reel before he left to the echo of resounding cheers. His parting suggestion that Niven play the bagpipes every day in order to lift the men's spirits was loudly applauded by physicians and patients alike. So it came to be that Niven walked among the wounded several times a day playing the pipes. At first, he felt selfish but, gradually, the mood in the hospital changed. Even the gravely injured soldiers looked forward to his visits.

Rowan never thought he'd eagerly anticipate the wail of bagpipes but had to admit there was something about it that lifted a man's spirits. His opinion of Niven King changed. It wasn't just the bagpipes that had kept him and many others alive. It was the man himself.

Niven had every right to hate the Halstead brothers. With Wellington's pass in hand, he could have been well on his way home by now, yet he insisted on staying until Rowan was fit enough to travel with him.

Rowan had resigned himself to reality—that day would never come.

One day, he was half asleep when he heard a commotion. Niven's bagpipes suddenly fell silent.

"No, no, no salutes, lads, no need," came an imperious voice he recognized immediately. Rumor had it the Earl of Uxbridge's leg had been amputated after the battle, yet here he was, navigating his way around the makeshift hospital on crutches, his aide following behind like a puppy dog.

"Thought I'd come and see how you lads are faring," Uxbridge boomed. "I see several of you, like me, are leaving a leg here in Flanders."

"Three cheers for the earl," someone shouted.

As the hurrahs resounded, Rowan could scarcely believe such a high-ranking officer had come to check on them. A personal friend of Wellington's, Uxbridge had been given overall command of the cavalry regiments.

"You chaps are lucky to have each other for company. The surgeons took my leg off at my HQ in the village. Nice little house, but no one to talk to about our great victory." He looked down his nose at the young soldier. "Except, of course, my aide."

The blushing youth smiled tentatively, clearly not sure if he was the butt of sarcasm.

Uxbridge pointed to Niven. "And you gentlemen have this young Scot to entertain you."

Heads nodded. Some cheered. Those still in possession of their arms and hands applauded.

"Piper McKay speaks highly of him, as do all the Camerons. Seems to be something of a mystery how he came to be involved in the fighting."

Rowan's gut knotted. So far, Niven hadn't revealed the truth, but every curious eye had turned to look at him.

"'Tis a long and convoluted tale, my Lord," Niven replied.

"Now I come to think on it," Uxbridge said. "I remember you from the docks in London. You went to a great deal of trouble to make sure my horse was properly settled aboard ship."

"Aye, 'twas me," Niven confessed. "I was tasked wi' takin' care o' the Duke of Withenshawe's contribution to the war effort."

"Withenshawe told me you're a member of the King family that distills Uachdaran whisky."

"One and the same, my Lord."

"Excellent libation! I used to be a brandy man, now my liquor of choice is Uachdaran . First thing when I get home I'll indulge in a wee dram as you Scots say."

Several heads nodded in endorsement of this prediction.

Niven smiled, then sobered. "The duke invested heavily in our distillery and has been a mentor to me. As a matter of fact, one of his sons is a patient here. Lost his leg, like you."

Feeling unreasonably piqued by the attention the earl was paying Niven, Rowan squared his shoulders when Niven led Uxbridge to his cot. "Marquess of Bracknell," he said, anxious to let the earl know he was speaking with a noble of higher rank. They might both have lost a leg, but Rowan was the eldest son of a duke, not a mere earl.

"You're Halstead's heir?" Uxbridge exclaimed, grabbing Rowan's hand. "We must get you home as soon as possible."

"But my leg," Rowan replied, immediately regretting the whining outburst.

Uxbridge scowled. "I'm not going to let the loss of my leg hinder me. William Halstead is a fine chap. Surely, his son has the same backbone."

As the earl was about to leave the farmhouse to the echo of more cheers, Niven took a chance. "May I have a word, my Lord?" he asked.

The aide moved between them but Uxbridge waved him away. "What is it?"

"I've sworn to get Lord Rowan home. Wellington issued me a pass, but I havena the means to get us both to the coast."

"I take it the pass was granted readily because you're not actually a soldier in the British Army."

"As I said, 'tis a long story how I came to be here. Nevertheless, I consider it my duty to get the duke's son home safely."

Uxbridge narrowed his eyes. "Admirable, especially since the marquess seems to have lost the will to survive and I sense it's not simply because of his injury. He's burdened by guilt, perhaps about your presence here."

Niven realized it would be foolhardy to lie to this perceptive man, but telling the truth might alienate him. "Aye. The long story involves a certain duke's daughter."

The earl slapped his good thigh and laughed out loud. "Might have known true love had something to do with it." He eyed Niven up and down, then said, "I've arranged for a carriage to take me to the coast in a week. Not quite up to riding yet and most of the good surgeons and physicians have left with Wellington. You and young Halstead are welcome to keep me company."

Fullepub

Fullepub