Chapter One

Catherine Keating knew she was giddier than she ought to be for eleven o'clock at night on a Thursday evening, but she'd ordered a cup of tea anyway, just because she could, just for the delightful novelty of having it brought right to the door of her boardinghouse room on a tray by a maid named Dot.

Go to London and make all the young men fall in love with you, her father had said.

Catherine frankly liked her chances.

Her dresses might be two seasons old, but she had new handkerchiefs, new gloves, and, thanks to the skillful social maneuverings of a certain Lady Wisterberg, more than a half dozen or so invitations to the season's balls and assemblies. And while she might not have much of a dowry, she did have her lucky necklace that had once been her mother's—a single pearl on a gold chain—and her mother's eyes—wide spaced, sky blue. What more did a girl need?

The plan had been impulsively hatched at a Lancashire house party a few months prior by Lady Wisterberg and Cat's Aunt Keating, who had been delighted when Catherine and Lucy Morrow, Lady Wisterberg's goddaughter, had got on famously. As Lucy had been staying with Lady Wisterberg in her crowded-with-relatives London town house, Catherine and her aunt had written to arrange for a pair of rooms at The Grand Palace on the Thames, a boardinghouse described by their village vicar, Mr. Bellingham, as Elysium by the London docks. The food! The company! The chandelier! he'd rhapsodized.

But much like the thrilling plot twist in The Ghost in the Attic, the story fellow guest Mrs. Pariseau had read aloud to the others in the boardinghouse sitting room this evening, at the very last minute Cat's great-aunt badly sprained her ankle and couldn't make the journey. Cat had reconciled herself to staying home.

Her father had insisted she go anyway. I'd like to see you settled, Cat. I won't be here for forever.

It wasn't a platitude. Her father was a physician, intimately familiar with the tricky intricacies of the human body and the infinite variety of ways in which it could fail, and his was failing. They both knew there was a reason he now needed to pause on the landing to get his breath as he went up the stairs, and why he struggled to travel miles in the dead of night to deliver a baby or sit by a dying man's bed. It was his heart. He and everyone who knew him had long taken for granted that his was as roomy, battered but indestructible as the old leather bag he carried with him when he went to his patients. But they'd buried her mother five years ago—she'd died after a short illness. And Cat suspected her mother had been half the reason her father's heart beat at all.

At the time, it had felt as though her own young heart had been hurled irretrievably into a deep well. Into every life, she supposed, came an event to which one must simply surrender and live through.

Bloom and decay, birth and death—nothing instilled pragmatism and awareness of the rhythms of life more than growing up in a small town in Northumberland as the only child of the only doctor for miles and miles. Cat wasn't inclined to self-pity. They were far from wealthy—her father had a habit of accepting things like dandelion wine or a piglet for payment when his patients were short of shillings—but there was little she'd ever truly wanted that she couldn't have, unless it was for people and animals she loved to live forever. She'd learned that everything beautiful and beloved was merely on loan. The gift in knowing this was that every moment now seemed as precious as currency, and every rare pleasure pierced.

And for these reasons, as much as she'd yearned for the excitement of a London trip, she'd balked at leaving her father behind for an entire month. They could only just afford it, besides.

I forbid you to worry about me, he'd said sternly. I'm not going to expire tomorrow, child, and I can do without you for a month or so. I've Mrs. Cartwright to persecute, er, look after me. Mrs. Cartwright was their beloved housekeeper. He'd said this within her earshot so she could squawk in happy outrage.

Cat was clever and her parents had seen to it that she was well-read and well-spoken, and her aunt and Lady Wisterberg asserted she was more likely to meet a similarly clever, educated, and well-spoken young man—who also had an independent income, and maybe even (thrillingly!) a title—in London than in Lancashire. The notion of this jostled her heart pleasantly.

The flare of a young man's pupils when a step in a quadrille brought their faces flirtatiously closer, the hitch in her breath when a strapping young fellow effortlessly hurled her trunk up onto the mail coach, the startling lunge and shock of lips on her skin when an inebriated Henry Thatcher had been overcome by ardor and kissed her on the cheek when they were both eighteen—all hinted at a world of sensual discovery awaiting her. All called to something earthy and restless in her nature.

And yet. While a few young men had tried to court her, none had yet infiltrated her imagination. She did not lie awake at night pining for any of them.

She did not yet know how shortened breath or a pupil flare evolved into love. She knew what love ought to look like: her father standing behind her mother, arms wrapped around her, watching the sunset in softly absorbed silent communication beyond conversation. He had courted her mother assiduously, and won her, or so went the story they always told; there had never been anyone else for him.

Surely she would know love by how it felt?

So in the end, she and her trunk had come in on the mail coach, accompanied by an older, widowed neighbor who had a few days' worth of business in London and would be abiding with her relatives near Covent Garden. Mr. Bellingham had assured both her and her father that the boardinghouse proprietresses, Mrs. Hardy and Mrs. Durand, were ladies through and through, and would look after her as well as her aunt would. Lady Wisterberg would look after her the rest of the time.

The notion that she needed looking after amused Cat. She was twenty-two years old. She'd once helped her father sew the tip of a man's finger back on. She'd once assisted in delivering a lamb. When his assistant had gone home for the day, she sometimes handed him bandages or ointments or lent an ear to any suffering patients who arrived after hours, and she regularly strode or rode alone around the countryside to neighbors' houses or into town—but only safe distances, familiar ones, because her head was about as level as a girl's head could be without being flat as a table. Nevertheless, she understood that if a young man wanted to meet her, he would need to ask Lady Wisterberg for an introduction. She would be the bulwark between Catherine and any whiff of impropriety, and quite possibly the sentry at the gate between Cat and her own moment of watching the sunset with a man's—perhaps even a titled man's—arms wrapped around her.

So Cat could foresee only delights while she was in London: she was looking forward to seeing Lucy again, as they had laughed a good deal together during the fortnight of the house party. Lucy was forthright and kind and enjoyed horrid novels and archery and vigorous walking about to see the sights. Her embroidery was exquisite and her watercolors abysmal, and for Catherine it was the other way around. Lucy had brought a tantalizing whiff of London sophistication into the country, as she'd often stayed there with her godmother, Lady Wisterberg, in her town house.

And as for The Grand Palace on the Thames, she'd seldom had a more congenial evening. Mrs. Hardy and Mrs. Durand were everything that was charming and kind. All the guests had been given a little glass of sherry after a delicious dinner of fish stew and a tart for dessert. And after Mrs. Pariseau had read aloud a chapter of The Ghost in the Attic, a story that fair had her nibbling on her nails in suspense (even though she wasn't certain she believed in ghosts) a funny man named Mr. Delacorte had gotten in the mood for singing. "Oh, I know what we should sing! I'll teach it to you, Miss Keating," he'd said. "It's a bloody good song. It has a clap in it, where you're supposed to say ‘arse'!"

This had caused an abrupt and reproachful silence. Whereupon Mr. Delacorte proceeded, red-faced and contrite, to an Epithet Jar and dropped in a penny. Everyone had been very understanding and murmured condolences and magnanimously blamed the sherry, as apparently, he'd gone for forty entire days without uttering an epithet in front of everybody else. To make him feel better about it, they'd all (with great reluctance, she noted, on the part of Mrs. Hardy and Mrs. Durand) sung the song he chose.

And it was a bloody good song, Cat thought to herself, mischievously. No wonder he'd been so enthusiastic about it. It was naughty, too. She'd been loudly and merrily singing it ever since she'd returned to her room a half hour ago.

Truthfully, neither "bloody" nor "arse" shocked her much; her father was known to passionately expostulate now and again. She knew better than to say them in company, however.

"Oh, I'm a man of great valor and honor, at least that's what he said before he climbed on 'er!" she sang as she pulled her night rail from the clothing press.

She was wholly delighted by her room, in fact.

Behind her, a veritable cloud disguised as a bed—she'd tested it with a bounce—was crowned with two equally decadent pillows and draped in a pink knitted coverlet. Perched on the little writing desk was a porcelain vase into which a fluff of white blossoms had been stuffed. The entire room smelled of spring, which meant it also smelled like hope. The blossoms had likely been plucked from the tiny, perfect park encircled by a wrought iron fence in front of the building.

The first of the London balls, at Lord and Lady Clayton's, was tomorrow night. Her heart took up a frisky tempo at the thought. With whom would she dance first?

She impulsively seized her pelisse to use as a partner and waltzed it around the room, singing: "‘Have pity,' he said, ‘have patience, I pray, I've a stick up me CLAP and gray in me hair!' La la la la—OH! Ow! Oh no—"

She'd spun herself and her pelisse partner into the desk chair.

Which teetered drunkenly, then toppled onto its back with a mighty crash that made her flinch.

She dropped her partner on the bed and crouched, rubbing her shin. "Good heavens, sir. It looks as though you may have imbibed too much this evening. Let me help you up," she said to amuse herself as she righted the chair.

A moment later she whirled again at a vigorous rapping on her door.

Lovely! Dot had arrived with her tea!

Beaming, she flung the door open.

And beheld a man.

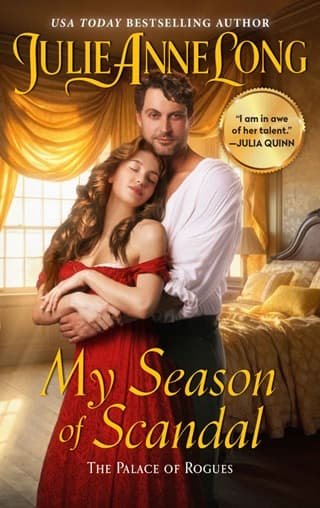

He was coatless. His cravat dangled as if he'd been interrupted in the act of clawing it off, his striped waistcoat hung open, and his thick, black hair was dashed into peaks, very like he'd plowed two tormented hands through it. A shocking, tiny little V of bare skin was visible at his throat. He also had the shoulders of someone who could effortlessly hurl a trunk up onto a mail coach, and the sculpted cheekbones normally sported by statues of deities.

She wasn't proud of it, but these last three things were what made her close the door only most of the way instead of slamming it.

"I came as quickly as I could, madam. Shall I send for a doctor?" His voice was a rumbling bass she could feel in her sternum. His tone was all urgent, hushed sympathy.

"I—I beg your pardon, sir?"

"Surely one only caterwauls past midnight if one has suffered the loss of a limb, or has inadvertently run oneself through with a fireplace poker."

He sounded so earnest, and his Welsh accent was so beautiful—the "s's" caressed, the "r's" gently rolled—it was a full three seconds before she realized this was a grave insult, not a benediction. He'd made the word "caterwaul" sound like a poem.

She was mute with astonishment.

Through the crack of the door, his fierce dark eyes seemed as endless as the universe.

"I—I'm terribly sorry if I disturbed you, sir. You see, I'm new to London and—"

He held up a hand. "Ah. Say no more. You hail from a place where you can freely wail the song of your people to the hills, like a wolf. Mere walls cannot contain your exuberance. Sleep is as nothing when you are filled with song. One simply must twirl."

Her stomach contracted against the sardonic onslaught. He was so beautiful and colorfully mean. Despite herself, she was perversely thrilled. He was an entirely new creature to her experience, and she'd come to London for new experiences.

He gazed back at her, radiating enough impatience for the entire human race.

"How did you know about the twirl?" She almost whispered it.

"Something caused the crash. I suspect cavorting."

Oh no. "You heard the crash, too?" Her cheeks were fully aflame now.

"The building juddered like a ship in a storm." He explained this slowly, as if to a child.

They regarded each other through the four inches of open door while a series of eloquent and scathing little rejoinders sparked and died in her mind. He was rude. She was no coward.

But her sense of fairness was powerful. However ignorant she was of the thickness of the walls, it was no excuse; she was in the wrong. And this man appeared to be under some sort of duress.

She cleared her throat. "Well," she said humbly. "I am abashed. I apologize. I was unaware of your proximity, sir. Thank you for calling it to my attention. I shall endeavor to be quiet."

"If you would be so kind." These last words were briskly, exasperatedly delivered.

His point unforgettably made, he spun and vanished from the doorway as if he'd never been.

She stared, blinking, into the space he'd left, her ears ringing as if he'd been a cymbal clash, instead of a man.

Presently she heard a clinking and rattling, which turned out to be Dot proceeding at a stately, cautious pace down the hall, bearing a tray of tea.

"Dot... who was that man?"

Dot glanced stealthily over her shoulder. "Lord Kirke." She said it very quietly. "He arrived late this evening."

Cat was stunned. "The Lord Kirke?"

Dot nodded slowly.

An eloquent look passed between them as Cat took the tray.

"Mr. Pike let him in," Dot told her with a certain grim satisfaction, as if this explained everything.

Fullepub

Fullepub