3. Chapter Three

Chapter Three

Cody

Parking my rented truck in the players’ parking area in front of the massive ice hockey arena, I ignore Mom’s call for the sixth time this morning. Focusing on the huge billboard on the front instead, I pull off my beanie and brush my hand through my hair. Aurora Arena—Home of the Aurora Mountain Lions. Shit. The butterflies in my belly are exceptionally hyper today. My phone chimes again, and I already know she won’t be letting up. Not until she’s had her daily fix securing her my-son-is-now-an-NHL-playerhigh. She started calling at 4:48 am because she knows I always set my alarm for 4:45 am to get in a morning run before hitting the gym. When I didn’t answer, she shot me the first text out of many.

Mom: Ready for your big day, hon? *screaming emoji* *hockey emoji* *trophy emoji* #proudnhlmamma

I just shot her a thumbs up as a reply, of course aware that it wouldn’t quench her need to bask in my success. It already started the night before when she lit up her Facebook page like a 4 th of July bonfire, tagging me in a string of never-ending self-promoting posts. A selfie of my platinum blond, five-foot-three mom in a pink onesie—size I’m-in-denial-of-my-age—with a roaring mountain lion on the front, the caption reading Proud NHL Mamma—when all your hard work and sacrifice finally pay off! #hockeymomforever

I stopped checking my phone after a post where she listed all her supposed sacrifices. How she raised me as a single, hard-working mom after my dad bailed on us when I was nine. How she fought tooth and nail, doing double— sometimes triple —shifts as a waitress to afford the hockey training fee and hockey camp. How she always encouraged me to ‘ Never stop believing, Cody, the sky’s the limit! ’ and stood by me when I had that serious—‘ but not so serious that it killed his NHL dream and his winning spirit! ’—meniscus tear when I played in the juniors in Phoenix.

We moved to Phoenix shortly after my dad and Danny left for Idaho, and that was it. Phoenix didn’t just mean a new reality, but also a new name.

‘ You’re a Mitchell now. Not a Manning, ’ my mom beamed at me, holding up my new social security card. ‘ Cody Mitchell. That’s a winner’s name. ’ She pinched my cheek. ‘ Not Manning. No Manning ever did anything remarkable in this world. Your dad’s living proof of that. ’ And just like that, my dad and my older brother disappeared from my life, right along with my old name. I continued playing hockey, shutting out all the outside noise, and as summer turned into fall, I learned how to react when my coach called out Mitchell instead of Manning . The rink became my safe place, the cool air allowing me to breathe freely. A place where I could skate away from a reality where my dad was far away, and no longer wanted me. A reality where Danny was ripped from my life, and I now felt like I was missing a limb. Whenever I skated, whenever I took my place in front of the goal, I could pretend that my dad and Danny were there, cheering me on from the stands. I never looked at the crowd. Not one single glance. It would only kill me when I would have to acknowledge that they weren’t there looking back at me with faces filled with pride and encouragement.

After I started showing real promise during my teen years, Mom pretty much took over micromanaging my life with only one result in mind as the outcome of all her hard work: to see her son play in the NHL. And it was my dream, too. Of course, it was, but for entirely different reasons than my mom’s. I want to play in the NHL because I love the game, and the game doesn’t get any better than when you’re playing against the best. That’s the way—the only way—I ever measured my success: to play against the best. It isn’t about fame or money. Or about dating some famous Hollywood actor or model. It’s about bettering myself every single time I set foot on the ice, pushing myself, improving my stats. Making your father proud , reminds that tiny voice that never leaves me alone. If you’re the best, you’ll make him proud. And if he’s proud, he’ll come back. The words seem as logical now as they did at the ages of nine, twelve, and eighteen.

Slamming the car door behind me, I shiver against the freezing January wind, tucking my chin against my woolen coat. I want to sprint towards the players’ entrance, but it’s too damn slippery today with virgin snow on top of a layer of ice. And I know better than to risk it—my knee is still prone to occasional flare-ups if I twist it awkwardly or have an unlucky run-in with an opponent. Reaching the entrance of the building, the automatic doors slide open, and I’m welcomed by the familiar smell of locker room, ice, and anticipation. The ice. I can’t wait to get out there, in the rink belonging to an NHL team. Sure, the Mountain Lions are nowhere near being a top League team, but it’s still a step up from the AHL. A huge step.

When my coach at the Phoenix Chasers, Coach Nichols, called me into his office in June of last year and told me I’d been scouted by the Duluth Dockers, the AHL affiliate of the Aurora Mountain Lions, I nearly tumbled from the blue plastic chair. Me, Cody Mitchell? At eighteen, I wasn’t drafted and signed to an NHL contract, and academically I wasn’t exactly college material either, so I played locally as a free agent and later in the AHL while working construction on the side. Of course, I’d hoped to play college hockey, but I wasn’t lucky enough to get that sought-after scholarship. So, to actually be signed, at the age of twenty-two. That was a dream come true.

‘Seems like you’ve caught the eye of some manager outta Duluth, son,’ Coach Nichols mumbled into his thick gray beard. ‘Hate to see you go, Mitchell, but I always knew that it was just a matter of time with a raw talent like yours. Still don’t understand why you ain’t playing for the Falcons by now, but I guess it’s their loss.’ Coach looked at the papers spread out in front of him on his cluttered desk. ‘It’s a good enough deal that they’re offering you, kid. Pretty sweet, to be fair.’ I was still trying to recover from the unexpected turn of events on an ordinary Tuesday afternoon, my mind coming up blank every time I tried to speak. ‘Now, there’s no guarantee that they’ll move you up to the Lions—they already have their goalies—but there must be a reason for the Dockers signing you.’ I nodded since it seemed the appropriate thing to do to signal Coach that I wasn’t stroking out on him, while at the same time digging my nails into the palms of my hands to make sure that I was, in fact, awake. My days of being a free agent were over at last. ‘You need to talk to your mom first?’ Coach Nichols scrutinized my face. Everyone in Phoenix knew my mom had the final say in every move—career or otherwise—that I made.

‘Yeah,’ I murmured, twisting my clammy hands in my lap, though I already knew that it would be a big fat resounding Yes! from my mom. She would have a field day, always making sure that I knew it was all because of her whenever I succeeded with something. When I failed, on the contrary, it was because I hadn’t practiced enough, focused enough, and wanted it enough.

The Chasers agreed to release me from my temporary contract, and after settling and playing in Minnesota, I was invited to the Lion’s training camp over the summer. The Lions already had their two first-choice goalies, but it was still a huge step up on the hockey career ladder. And now, seven months later, the Lion’s first goalie, McKinney, has a busted right shoulder and is out for the rest of the season. And suddenly, overnight, I have, at the age of twenty-three, become an NHL goalie. And even though I’m not the first choice, I’ll still get to practice with the team and probably play a few games, too. And who would’ve thought that this was where I would end up when I started playing hockey at six years old? Now I just need to make a good impression, proving to the team that they were right in signing me and that I can deliver, even when all eyes are on me, the rookie.

“Can I help you, son?” A middle-aged man with a cleaning trolley next to him looks up from where he’s sweeping the already very pristine floor.

“Morning, sir,” I offer the man, rubbing at my eyes. I slept for shit last night, tossing and turning in the luxurious bed in the fancy hotel close to the airport provided by the team. Their extensive administrative team has already taken care of my temporary housing, but I arrived late last night so it was easier to stay at the airport hotel. I know from an email from an administrative secretary, Ashley, that I’ll be moving into the condo where McKinney has been staying with one of the team’s D-men. At least until I can afford my own place. “I’m looking for the team,” I blurt, cursing myself. “Sorry, for the team area, I mean,” I add, my cheeks heating. Smiling at me broadly, the janitor pauses what he’s doing and takes me in properly. “I have a meeting with Coach Bassey,” I clarify.

“You that new kid? The goalie? Coach mentioned you’d be coming in today.” The older guy leans against his broom, a welcoming expression on his face, fine lines crinkling at the corners of his eyes.

“Yeah. I’m Cody, sir. Cody Mitchell.” I reach out my hand and the janitor wipes his right against the front of his blue coveralls. Accepting my hand, he winks at me, while shaking it firmly.

“Well, mighty nice to meet you, Mr. Cody Mitchell. I’m Hal, the rink janitor. Anything you need around here, you just let me know, okay, son?” He smiles, continuing to shake my hand eagerly, eyes beaming with nothing but genuine excitement. “Used to work down at the City Hall before I landed this job, so if there’s anything you need to know about Aurora, I’m your guy.”

“Thank you, Hal. I’ll make sure to do that,” I release my hand from the older man’s. “So, the team…?” No way I’m going to be late on my first day of practice. In her email, Ashley informed me I have a brief meeting at 8 am with Coach Bassey—yes, the Jamal Bassey—followed by a thirty-minute tour of the facilities by one of the assistant coaches, and an introduction to the medical staff. Then, I get to meet the team. Great, I’m sure that they’ll be just thrilled after they’ve been briefed about McKinney.

“Yeah, yeah, down that hallway and to the left. Then, at the end, there’s a double door. To the right is Coach Bassey’s office, and further down the hallway are the locker rooms, the gym, and such.” Hal points in the direction of a long hallway. I follow his finger and nod in acknowledgment.

“Okay, thank you very much, Hal. I’ll see you later.”

“Sure thing, Cody Mitchell. I’ll be seein’ ya around,” Hal grins before resuming his task of sweeping the floor, whistling quietly.

Hal’s directions are easy enough to follow, and after a few minutes, I find myself standing in front of the double doors to the team training facilities. I’ve been mostly calm this morning, still in a state of disbelief and pent-up excitement, but as soon as it settles inside me that behind those doors an entirely new life awaits, I recognize the familiar tightening in my chest.

It’s hard to describe, really, if you haven’t experienced a panic attack yourself. It feels like something heavy and unmovable has decided to sit on top of your chest. You can still breathe, but every inhale feels restricted and painful, and every exhale comes out in clipped pants. Sometimes it feels like I’m dying. That my heart can stop beating any minute. That every breath will be my last. Rationally, of course, my mind knows that I’m not dying but my body seems to think so, and the physical reactions are no joke.

I remember the first time I experienced one. It was a week before my tenth birthday, and I asked my mom if Dad and Danny would be making the trip from Idaho to celebrate with us. She looked at me, her eyes made up with heavy make-up as always, making her look like a raccoon. Pouring herself a glass of wine, she sat me down at the kitchen table, inspecting her red nails as she spoke.

‘ You need to forget about your dad. The sooner the better. He doesn’t care about us anymore, Cody. He has Danny and I’ve got you. ’ As her words settled in my head, the room started spinning, and for a few minutes—or perhaps it was only a few seconds—I couldn’t see or hear anything. All I could feel was the overwhelming rush of blood in my head and the sour taste of bile in my mouth. As my mother shook me, her mouth moving soundlessly in front of me, one question went on to repeat in my head. A question that still pops up from time to time. Who do I have? Who do I have?

These days, my anxiety mostly surfaces when my mom goes on one of her ‘ woe-is-me ’ rants, listing everything I, Cody, owe her, Mom, for sacrificing her youth and beauty—let’s not forget her title of Miss Logan back in 1995. It usually starts with a slight tunnel vision and that familiar ringing sound in my ears before it transfers to my hands, my fingers tingling, my palms growing clammy until, eventually, my chest starts tightening. It rarely morphs into a full-blown panic attack, but it’s still scary as hell—the loss of control. The feeling of being suspended over a great abyss of nothing but an all-consuming feeling of fear. The only thing that’ll usually pull me back from the claws of that feeling of pure dread is the sound of my dad’s calming voice. I can still recall the distinct deep hum if I concentrate hard enough, safeguarding it deep inside where my mom’s shrill nagging and accusations can’t reach. ‘ You ready, bud? You ready, bud? ’

‘ You ready, bud? ’ Dad patted my helmet, a proud glimmer lingering in the cool gray of his kind eyes, his warm, coffee-tinted breath coasting across my face.

‘ I think so, Dad. ’ I tugged at my bottom lip, gazing around the rink where a group of kids my own age were already on the ice. Some looked pretty advanced, skating at a constant speed as they swept across the ice. Others looked like newbies like me, legs wobbling, arms grabbing desperately at the air in front of them. Rows of enthusiastic parents with rosy cheeks and eager eyes glaring at them, the occasional ‘ oohs ’ and ‘ ahhs ’ spilling from their mouths followed by a ‘ Nice try, hon, ’ or ‘ There you go, sweetie. ’

‘ You’re ready, Cody, ’ Dad winked, getting up from where he was crouching in front of me. Six. I was six, and I’d been nagging my dad for eight months now that I was old enough to start playing hockey. Kids in our neighborhood who were way younger than me were already playing for the Cache Valley Jr. Aggies at the amateur hockey club in my hometown, Logan, Utah.

Of course, my mom was opposed to the idea. It was too expensive, too time-consuming, too dangerous, too blah-blah-blah. From an early age, Danny and I had learned to change stations when Mom went into one of her ‘ I-do-everything-around-here-and-what-do-I-ever-get-in-return? ’ tirades. It wasn’t often that my mom listened to anything I and Danny had to say in the first place, and when she did listen—‘ I’m listening, Cody, so speak ’ — she interrupted more than anything else. So, I’d nearly given up, resigning to the fact that hockey was an unattainable dream. Dad was mostly away for work, and Danny and I usually stayed out of Mom’s way when she was in a mood, which was pretty often. It wasn’t that I’d stopped talking about hockey—I still dreamed of becoming the next big hockey name out of Utah—it was just a quieter dream. A dream that I would tuck away during the day and unwrap at night when I was lying in bed, telling all my secrets to Trevor, whose poster adorned my back wall.

Funny how my mom was the first one to take credit when I, at the age of eight, became Player of the Year—which was the first for a goalie as long as anyone could remember in Logan. Dad just shook his head, an ill-disguised smile tugging at the corner of his mouth, when Mom praised herself for being steadfast— steadfast, Glenn —in her unwavering belief that I had a raw talent and that he should be grateful that she’d recognized it when no one else had. One year later, when I once again received the sought-after title, there was no proud dad smiling back at me when I gazed down at the small trophy on the kitchen table, trying to tune out Mom’s Mother-of-the-Year rant.

No, Glenn Manning was long gone by then, somewhere in Idaho with Danny, and his departing promise ‘ I’ll see you soon, okay bud? ’ had been exactly just that. A promise. One that remained unfulfilled over the years until there was nothing left except faded pictures in a photo album and the ghost of my dad’s voice. Until there was nothing left but Mom’s inconsistent explanations that ‘ Your daddy doesn’t want you anymore. He’s made a new life for himself with Danny in Idaho. Good thing you still have me, baby. I’ll never leave you. I’ll always be here. ’Even at age nine, I remember thinking that Mom’s words sounded more like a threat than a comfort. ‘ I’ll always be here. ’

“I know, I know,” a warm voice washes over me, pulling me back from my bittersweet memories. “Story of my life. Always fucking late.”

“Well, get a move on then, Carrington,” a much deeper voice thunders down the long hallway, echoing off the walls.

My heartbeat has settled back into its normal thump, thump, thump when two guys around my age blow past me in a semi-jog, joking and throwing playful punches at each other.

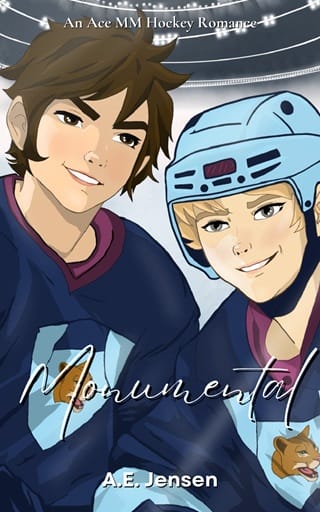

“Hey, man.” The shorter of the two turns around, and I’m met by a pair of deep brown eyes and a broad, toothy grin. Luke Carrington. One of the Lions’ D-men and our biggest asset, if you ask me. A good-looking guy by any standard, with his wavy, dark brown hair, and his trademark crooked smile.

“Hey,” I mumble, shifting on my feet, my nerves suddenly back. It’s real now. This is it.

“You going in?” Luke continues to smile at me, his brown doe eyes searching mine, his cheeks flushed red from the cold. Taking a deep breath, I brace myself while attempting a smile. You’ve got this. You earned it. You deserve it, I give myself an internal pep talk.

“Yeah. Yeah, I’m going in.”

Fullepub

Fullepub