Chapter 1

Griffin

“Griffin Marsh, please rise.”

I kept my back straight and willed my knees not to shake as I stood. I’d been staring at the polished top of the defendant’s table, but now I raised my eyes to meet the judge’s cool gaze. She frowned down at me.

“Mr. Marsh, you’ve pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter for your role in the accident that killed Linda Bellingham. This hearing is not to further assess your guilt, but to determine your sentence. Do you understand this?”

I cleared my parched throat. “Yes, Your Honor.”

“You’ve heard the victim impact statements presented by Linda’s family?”

“Yes, Your Honor.” Her seventeen-year-old daughter wanted me crucified for knocking her mother’s car down the embankment, but Linda’s husband had been calm and measured and kind enough it brought tears to my eyes. He’d even said, “I’ve looked away from the road to reach for something a time or two. I was lucky my carelessness never resulted in disaster. Linda and Mr. Marsh weren’t that lucky.”

I wish I could go back. I wish I’d pulled over before reaching down for my fallen phone. I wish, I wish, I wish. I gritted my teeth, choking down the tide of regret, because at fifty-six, I knew very well there was no way to turn back time. I wish I’d crashed my own damned car down the embankment and missed hers.

The judge nodded slowly. “Your pleading guilty to the misdemeanor charge, rather than demanding a trial on the potential felony, gives me fairly wide leeway in deciding your sentence.”

That didn’t seem to demand an answer, and anyway, I wasn’t sure what I would say. A small, ashamed part of me wanted to go to prison, to be punished properly. Even the misdemeanor could put me behind bars for two years. I deserved that, didn’t I, for ending the life of a bright, healthy, vibrant teacher and mother of two? But the bigger part of me was terrified of prison, desperate to stay free. I’d hired a top lawyer and done everything she suggested to avoid that punishment. I’m a coward.

I sucked slow breaths past my clenched teeth. My knees shook despite my determination, and I clutched the edge of the table.

“You have no prior convictions, not even traffic citations.”

That was pure luck, because I liked to speed— had liked to— but I’d never been caught. A blessing now, when every little flaw mattered.

“Your contrition as expressed during your statement seems genuine, and I applaud your establishment of an education fund for Mrs. Bellingham’s two daughters. Six-hundred-thousand dollars is well above the maximum fine I can levy for this crime.”

I heard Linda’s teen daughter in the audience shout, “I don’t want his money!” and be shushed by her father. Her younger sister wasn’t present, thank God. Looking at a grieving seven-year-old would’ve broken me. I hoped their father would convince them to take the cash. It was all I could offer, almost all of the savings cushion I’d accumulated after three decades of not-quite-rockstardom. I had enough left to pay my lawyer, plus the maximum fine, which was a petty seven thousand dollars, and leave enough to live on for the next few months.

If I’m not headed to prison. My vision went a bit wavery, the judge’s face a blur. I tried to meet her gaze. Keep it together, you wuss.

“I do not believe any useful purpose will be served by having you undergo a term of incarceration at this time,” the judge said.

Thank you! I shuddered with relief, still white-knuckling the table.

“I therefore sentence you to two years, suspended, to be served on probation, plus five-hundred hours of community service, and a fine of six thousand dollars. I further direct that your community service be performed at one or more long-term rehabilitation and nursing homes, the type of facilities where Mrs. Bellingham might’ve ended up if she had survived the accident. You and your probation officer are to complete a plan and submit it to this court no later than the fifth of next month. In addition, your driver’s license will be suspended for the next twelve months. Do you understand your sentence as I have described it to you?”

“Yes, Your Honor.” My voice came out squeaky and I cleared my throat. “Thank you, Your Honor.”

She picked up her gavel and rapped sharply. “This hearing is adjourned.”

As the judge pushed to her feet, the bailiff intoned “All rise.”

My lawyer, the prosecutor, and the few spectators stood with rustles and shuffling. When the judge had left the room, my lawyer turned to me, her hand held out. “I told you we could keep you out of a cell.”

“Yes, thank you.” I was aware of my damp palm as we shook hands, but she didn’t react. I was no doubt far from her first nervous client. She probably had wipes and sanitizer in her briefcase. “What happens next?”

“You’ll be assigned a parole officer, and a community service plan. That likely won’t happen until next week at the earliest. Once you do have a parole officer, remember his or her word is your law. Do not miss meetings or blow them off. Screwing up your parole will land you back in front of a judge.”

“I won’t. I swear. And right now, I do what? Just drive home? But my license was revoked.” I felt totally adrift. My whole existence had been on hold until this day and now the worst hadn’t happened, but the ground had still shifted under my feet.

“Your license will be seized but you get a seven-day temporary to wind up your transportation needs and move your car to a secure location before you lose the right for a year. I’ll walk you through that process.”

For an additional fee, no doubt. But I was super lucky to have been able to afford her. I bet a public defender wouldn’t shepherd their client along the way Ms. Fisher had guided me.

Her cool expression eased into something warmer. “I’m glad for you, Griffin. I’ve defended a lot of people over the years, and you’re one of the ones I felt privileged to help.”

“Privileged? I was guilty. They could’ve charged me with a felony and put me away for ten years.”

“You’re a good man who made one stupid mistake, and someone else paid a big price. That doesn’t make you a bad person, and putting you in jail would’ve been a waste of public money and made the world worse, not better. So win, win.” She gave the first full-fledged smile I’d seen from her. “I do like days when we win.” She sobered as she continued to meet my gaze. “Can I give you a bit of advice of a non-legal nature?”

“Um, sure, of course.”

“Think again about seeing a therapist. Just a few sessions, anyway. I’ve defended other clients who went through something like you did, and it takes a toll.”

I didn’t go through much. Linda and her family lost everything. And I hadn’t held back any of my money for therapy. But I nodded because she meant well.

“I hope you start songwriting again, and performing. I looked up your work when I took your case and you’re very talented.” She gave me a firm nod. “Come on, let’s get your paperwork and license sorted out.”

When we reached the hallway outside the courtroom, a middle-aged man hustled up to me, pen and notebook in hand. “Griffin! Do you have a statement for your fans? How does it feel to know you killed someone and got away with it? Will you write a song about this experience?” Luckily, there were laws about cameras and recording in the courthouse so he didn’t get a photo of the expression on my face. My glare did make him recoil a step. Two other reporters hurried over, though, calling questions.

My lawyer’s nudge on my arm reminded me to grind out a simple, “No comment,” through gritted teeth. She hooked a hand in my elbow and guided me down the hall.

The reporters followed, asking questions and making suggestions. Luckily, as we stood in line for documents, the first guy made himself annoying enough that a guard ushered him out of the building. I glared at his retreating back. The other two didn’t shut up, still calling out their bullshit, but they stopped trying to get in my face. After a minute, a different security officer appeared and sent them on their way despite their protests.

“How does it feel to know you killed someone?” That reporter wasn’t the first to ask me that question in my long slog through the justice system. It feels like shit, what do you think? I’d never tried to answer out loud. They wanted sound bites and juicy gossip. Anything I said, they’d twist into either “He’s suicidal,” or “He’s a remorseless monster.” Maybe both.

“The downside to being famous,” my lawyer noted, watching the reporters escorted away.

“One of them, yeah. Not that I count as famous anymore, or there’d have been more than a couple of hacks with pencils and cell phones waiting.”

“Still. I can get us out a back way when we’re done, if you like.”

Hiring her had been my best recent decision. Not that the bar was set high. “Yes. Thank you!”

Two hours later, I pulled into my parking space outside my apartment and turned off my SUV. The engine ticked as it cooled but I didn’t even have the energy to open the door. Driving still wiped me out. I had to force myself to start the car, and every moment on the road put me into hypervigilance, my hands at ten and two, waiting for disaster. I arrived with my shirt clinging to my damp skin. Maybe I should see a therapist. Then again, I wouldn’t be driving for a long time now. Worry about it later.

I needed to find somewhere to garage the SUV. Or maybe I could lend it to someone who’d take the vehicle out now and then and keep the engine running. The insurance company had paid to repair the damned thing after I wrecked it. No sense letting the battery become a brick through disuse. Maybe I had a friend who’d find free transportation useful.

If I had any friends here. In LA, not a problem. Some of the folks I knew well were still touring, but several had retired and started families. I could’ve called Mandy or Nic, or Pete if he was around. Here, in my hometown, I was as alone as I’d been when I was a child.

Other than once, for a few magical weeks, Iowa had never been a lucky place for me. Coming back here to sort out Mom’s things from her storage unit, four years after her death, had been the biggest mistake I’d ever made.

Now, I was stuck in the state for two years… I deserve worse. Listen to me bitching about being stuck, while Linda’s stuck being dead!

I pressed my hands to my eyes. I wish. For the hundredth time, maybe thousandth, other accident scenarios ran through my head, the what-ifs and might’ve-beens.

I could’ve not tried to shake out a cramp in my right wrist and knocked my phone out of the cup holder. So goddamned clumsy these days.

Or I could’ve let that phone lie on the floor by my feet, even if the tinny voice said it lost GPS signal. So what? I was driving on a straight road.

If I needed the phone, I could’ve pulled off onto the shoulder and stopped somewhere. Reached down safely. Sure, merging back into fast traffic from a standstill is a pain, but so is death.

When I realized I couldn’t reach it by feel, I could’ve stopped trying, instead of taking my eyes off the road for “just a second.” Who fucking cares if there was a good space ahead and traffic was moving well? That one second changed everything.

Or when I looked up and saw brake-lights, saw that Linda’s car had abruptly slowed due to a fallen box in the lane, I could’ve pulled to the right instead of left. I could’ve missed her by plunging off the embankment, or at least, whacked her toward the median and rolled my own SUV down the hill instead.

Half a dozen tiny changes, moments when fate could’ve been altered if I’d been smart, careful, aware, different, just somehow different. I’d give anything to make it different. If I was the one who’d rolled down the embankment and died, a lot fewer people would’ve really cared.

In the dark behind my closed lids, the accident played out in lurid color and sound, flashes of red lights and painted metal, bangs and crunches, and then in the silence as the airbag deflated, someone screaming. Not Linda. She was dead by then.

I wish, I wish, I wish.

Of course, as my mother used to say, you can wish in one hand and shit in the other, and see which one fills up first.

After ten or fifteen minutes when reality didn’t change, I forced myself to straighten, opened the door, and got out.

And, fuck my life, that same damned reporter popped up from behind a parked car, a camera pointed my way. “Griffin, over here. You lucked out and weren’t sentenced to prison time. How does that make you feel?”

I lowered my head and trudged toward my building’s front door.

“Don’t you want to tell your side of the story? The Bellinghams will be telling theirs.”

No, I really don’t. I kept my eyes fixed straight ahead. Don’t look down— it appears guilty. Don’t look at the camera— they will isolate any expression they choose. Had he filmed my mini-breakdown in my car?

I’d been in front of the media half my life but the rabid, bloodsucking attention of the last few months was a whole different thing. I ignored the camera guy sidling up next to me, lens fixed on my face, as I unlocked the door to the lobby, slipped in, and locked up behind me, the reporter on the outside.

He was still filming through the glass door so I didn’t stop to check my mail. The safety and solitude of my room was all I wanted.

My apartment held a stale scent of fake lemon and bleach. I’d cleaned frantically to fill the hours before the hearing. Everything I owned was tidied and packed up. If the judge had decided on a prison sentence, the bailiffs would have taken me into custody and headed me off then and there. My lawyer would have arranged for the end of my lease and for storage. I’d left this place not knowing if I’d ever come back to it.

Relief hit me so hard my whole body shook. I staggered into the living room and dropped onto the couch.

I’m not going to prison.

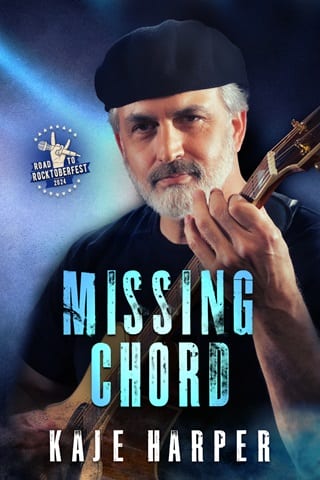

I was torn between laughter and tears, choking and snorting, hugging my middle with trembling arms. I thought my head might float off my neck like a balloon. There was only one thing I could do to keep myself together. Pushing to my feet made my head spin, but then I got my balance. My Gibson was my favorite composition guitar, the one I always carried with me, and bringing it on this ill-fated trip had been a lifesaver. I’d left it packed in its case, laid on the coffee table against the wall, well out of the sunlight. I opened the hard lid and lifted the guitar out. The faint hum of the strings as I moved the instrument soothed my soul.

Seated on the couch again, I tuned the strings from the tone down I’d given them for long-term storage. Every touch, every note, made my breath come easier. And for the first time in seven months, words surfaced.

Isn’t it funny

In a cold cruel way

That a life on the fly

As the years roll by

Hits a prison wall

How the smug can fall

In the blink of an eye

Watch the future die

Can’t wish death away

Isn’t it funny?

The lyrics were clunky and rough, but the tune had something, a hook plaintive enough to linger in my mind. I couldn’t do more right now. My head was in the wrong place to dive into composing. Introspection lurked like a deep dark hole I hadn’t let myself peer into since the moment that airbag punched me in the face. I’d grown adept at blocking my thoughts with chanted distraction every time my brain tried to dive. Don’t think, don’t think. Still, I got up and fished a pencil and notebook out of the pocket of the guitar case and jotted those few notes. It never hurt to write the rough start down.

Then I took myself and my guitar back to the couch, propped the pillows behind me just right, and played. My old standards, then covers, songs I played ten years ago, twenty. At first, I ran through the lyrics in my head, not trusting my voice, but on “Water Over the Bridge” I couldn’t help singing. Twenty years ago, I debuted that song in a local venue, when I came home to take care of Mom after she’d had a fall.

The bar had held maybe fifty people and it was crowded, folks coming to see the local boy starting to make good. I’d played a couple of big festivals by then. My first single had made it onto the charts. A smoky haze hung over the crowd, part tobacco but with a hint of pot, the smell echoing eighteen years of trying to break out of the pack with my songs, of a hundred bars and clubs smaller than this one. I’d breathed in deep and leaned toward the mic, said, “I have something new for you folks. I hope you like it.”

In the moment before I sang the first note, I’d spotted a cute guy watching from a table in the front. A redhead, his curly hair a bit long and artfully messy, his round, smooth face and full mouth hitting my hell-yes button. I kept my eyes on him as I belted out the first line. The first time I saw Lee.

Twenty years back, that memory would’ve hurt me to the core, but now it felt bittersweet. One more time I’d screwed up, but no one had died. We moved on. I was pretty sure Lee was partnered up by now and living his good life. Sweet man like that, he probably had half a dozen adopted kids and a golden retriever.

Still, it’d been prophetic, perhaps, that the first time our eyes met I’d been singing that song.

Nothing gentle ’bout the water,

Nothing kind about the tide,

Drives my life over the railing,

Blasting force and I can’t hide.

Tumble down,

Rocks below,

Can’t hold back,

Here I go,

Did I say I want adventure?

Want the world to open wide?

Grab on where my songs can take me

And embrace the rising tide.

My songs had taken me away from Lee, in the end. My biggest regret, until now, and yet a choice I’d made with my eyes wide open. I’d had so much luck and loss in the twenty years since, rising and falling in the music world, but Lee had lingered like the fading scent of roses in my head. Now, of course, I’d done far worse than walk away from a man with a kind heart. I’d hit those rocks, and not the ones I expected. I’d dashed another life to bits on them. I wondered, as I played the instrumental bridge and let the words die, if this tide would drown me.

My phone buzzed. I set the guitar aside and reached for it, realizing my fingertips stung. Unknown number. I’d learned to answer those, in this process of navigating courts and laws. Which of course meant I’d answered every telemarketer and sleazeball journalist around. I hung up on a dozen calls a day. I tapped the green. “Who is it?”

“Mr. Griffin Marsh?” a man asked.

“This is he.” My lawyer told me never to say “Yes” to random callers who might record me and misuse the word for fraud.

“I’m Officer Daniels, your assigned parole officer. We need to set up your initial meeting. I’ll explain the rules, and we’ll plan your community service.”

I straightened my shoulders, even though he couldn’t see me. “Yes, of course. When and where?” Apparently, staying on the good side of your parole officer might mean the difference between pleasant community service and permission to travel, versus two years of cleaning toilets. I was generally good with strangers, but I had a hell of a lot more incentive here. “You name it.”

“Are you currently working?”

“I’m a performer. I have no gigs at the moment.” I’d backed out of almost all my commitments beyond this date. Better to give notice far enough ahead to be replaced, rather than earn a name as a no-show deadbeat criminal. The music biz was all about your reputation, so I’d done the honorable thing.

Except Rocktoberfest. That invitation was far enough out and precious enough I’d kept it, just in case. October. I had no clue what my life would look like three months from now. I told Daniels, “My time’s pretty open.”

“Tomorrow, eleven a.m., then. The sooner we run your plan by the judge, the sooner you can get started on your hours. I’ll text you’re the address and room info.”

“Yes, sir. I’ll be there.”

He cut the call without a goodbye. A minute later, my phone pinged with an incoming message.

Tomorrow. One more step in this nightmare journey I’d set into motion in a stupid, careless instant. But was it nightmare enough? Did I deserve a calm if brisk voice on the phone, asking about my prior commitments? I’d cleaned toilets a few times in the dozens of brief jobs I’d held and dropped, quitting when a conflicting gig opened up somewhere. Would I feel better if Daniels did set me to manual labor? Did I deserve to feel better?

The swirl of that repetitive mess in my head made me close my eyes. Don’t think. Don’t think. I should probably eat, but my stomach said a hard no to that. Don’t think. I resettled the guitar on my knees, pressed my tender fingertips to the strings, and played on.

Fullepub

Fullepub