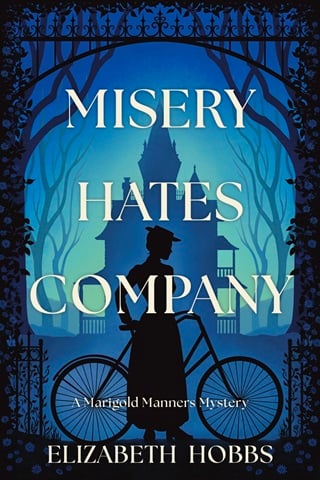

Chapter 5

C HAPTER 5

The emerging woman … will be strong-minded, strong-hearted,

strong-souled, and strong-bodied … strength and beauty must go

together.

—Louisa May Alcott

Marigold would not countenance the notion of bad bloodlines—people made their own choices, regardless of their family's blood. "Yes, well," she said in her crispest tone to dispel the ridiculous feeling of foreboding. "I am quite sure I will."

What she also saw as she attempted to put her back to the oars, was that, despite being an experienced oarswoman, she was making little progress.

"Tide's running in," Cleon remarked unhelpfully. "Shoulda waited on the ebb. Be a long pull out to Mis'ry."

Marigold stiffened her determination along with her spine and braced her feet hard against the thwart. The light was rapidly fading, and over her shoulder, the dark hulk of the island seemed to be dissolving into the sea. "How far is it exactly?"

"A good long pull," he repeated imprecisely.

But to the west, the sunset painted the shore in deepening amethyst, turning the water as Homerically wine dark as she might have wished. She wouldn't have an archaeological summer field season on Kefalonia, but she would still work on the translations of the early Greek myths and fables she had planned for her honors paper. She would find a way to progress even if she wasn't at college.

A flash of contrasting color—a wine-dark mulberry red, like the velvet dinner dress she had packed because, well, because she had packed everything in her possession—swirled past like the flotsam of a shipwreck. And then it was gone, leaving Marigold staring at the water, wondering if she had only imagined it.

No—there it was again, just below the gray surface of the water, truly wine dark and not just the product of her ancient-Greek-literature-influenced imagination! "I think there's a woman—there!"

Cleon spared the barest glance over the side but did nothing more.

Marigold was not used to being ignored. "There is something—or someone—in the water," she insisted, shipping the oars. "There!" She pointed over the side.

It was real and not some overwrought, literary vision. An apron, perhaps?

Marigold leaned over the gunwale toward the water. "Do you not see it? Pass me that rope or net or whatever—"

She reached out blindly, trying to keep sight of the flash of color through the dark waves, only to be met with a shock of pain ricocheting up her arm from Cleon ineptly trying to pass her the spruce spar instead.

"Cleon! Careful!" she cried, forcefully enough to make him cower away. Marigold snatched the offending oar from his hand and snapped it back into its proper place in the rowlock. "What on earth do you think you're doing?" Only the fact that she was strong and athletic had prevented her from being struck senseless. "You might have knocked me overboard!"

Cleon slumped back into the stern. "Pardon, Esmie's girl," he said by way of apology. "Din't mean nothing by it."

"It was extremely careless. Not to mention ill-timed." Because whatever it was she had seen—and she had seen something—was gone in the cresting waves. "We've lost whatever it was now."

"Din't see nothing myself, Esmie's girl," Cleon finally offered. "Nobody oughta be in that water this time o' year. Too cold and too fast."

"Naturally," Marigold agreed more reasonably than he deserved. "That's precisely why I wanted to help." But there was no one to help now. Marigold finally resumed rowing but kept a careful, if stern, eye upon the addlepated idiot.

Who remained cryptic. "Takes some getting used to for some peoples, Esmie's girl," Cleon mumbled into his soiled beard, as if she were the one making mad suppositions. "The lonely ocean."

Marigold felt herself bristle like a cat with its fur rubbed the wrong way. She was not "some peoples." She was a rational creature of sense and logic and integrity, and she knew what she had seen—the color and shape were impressed upon her brain.

She had seen something .

Marigold took her frustration out in the rhythmic physical exertion of the long pull, straining somewhat at the oars in the rougher water midsound, but by the time she finally piloted the dory into a small, rock-bound inlet on Great Misery Island, her forearms ached and her hands were cramped and sore, with blisters beneath her gloves.

Nothing but years of rigorous self-discipline and an unqualified belief in herself kept her from showing any sort of consternation—or any symptom of her present injuries—when the chilly inlet proved as empty of any greeting relation as the station had been. Or from showing any sign of alarm when Cleon simply abandoned the dory and wobbled away into the gathering night.

"What about the boat?" Marigold called as she struggled to pull the heavily laden vessel up the sand, past the high-tide mark, where it wouldn't float away. "And my luggage?"

"S'pose you oughta take what you'll need for your comfort," Cleon advised over his shoulder. "Reckon someone'll have to come back with the mules for the rest."

As loath as Marigold was to abandon her luggage a second time, she was even less eager to be left behind in the eerie wilderness of her cousin's estate. She quickly snatched up two of her nearest valises and raced after Cleon, down a rough track leading into the darkened woods.

The night seemed to close in around her, and the sounds of the woodland—the beats of unseen wings and the scuttering of creatures behind the tumbled-stone walls—set her surprisingly susceptible heart to racing.

And that would never do. Marigold took both her imagination and her baggage firmly in hand to keep from letting the clammy discomfort shifting between her shoulder blades unsettle her.

On they plodded—well, Cleon plodded, while she trudged along under the weight of her bags—following the rutted trail that meandered like a deer path across the arcadian island.

It was nearly full dark when the woods at last gave way to a clearing where a single flickering lantern gave scant illumination to a number of structures—a larger, darkly shingled edifice, several shacks, coops, or sheds, and a weathered, tumbledown barn—all perched along the granite-strewn edge of the sea, hulking in black silhouette like crows over a carcass.

Marigold shook her head to dispel such a dire, illogical image—real life was not like the imaginings of a Gothic novel. But she couldn't help asking, "Is it much farther to the main house?"

"This be the house." Cleon pointed to the dilapidated shingled building. "Cursed it is." He spat out the side of his mouth as if he could rid himself of some evil. "And us'n all with it."

Unease cloyed across Marigold's skin like a cobweb, insubstantial but still keenly felt. If before she had imagined herself in one of Mark Twain's stories, now she felt as if she had chanced into one of Edgar Allan Poe's—she would certainly be leery of any cellars or casks of amontillado.

But it took only a moment before she reasoned that Cleon's mutterings were likely the second of two painfully obvious attempts to scare her out of her rights. The Hatchets were likely proving themselves reluctant to part with whatever inheritance she might be owed—however unlikely the chances of such a shoddy place providing any inheritance might be.

And if Hatchet Farm wasn't the private estate she had imagined, it still harbored the potential to become one—the real estate had value even if the farmstead had fallen into disarray.

Up close, the house was a moldering, Gothic-looking pile, clad in warped clapboards topped with blackened, cedar-shake shingles. It might have once been an imposing edifice, but the present appearance of the place was quite persistently dismal—all skewed angles and shuttered gables without a glint of light or warmth. The shiplap framing the entry was cracked and canted as if the place had withstood successive years of Nor'easters with nothing more than salt and spite.

Presently, the chapped front door creaked open and a wizened woman held a flickering oil lantern high. "Be that Esmie's girl?"

The old woman was dressed in clothes nearly a century old, with worn patches at the wrists and elbows, and her shoulders were draped in at least two layers of shawls. Gray and black-streaked hair wreathed her pale, lined face.

The word crone rose unbidden on the tip of Marigold's tongue, and nothing but the strictest application of her best manners prevented her from speaking the term aloud. "Good evening, ma'am." Marigold nodded graciously to the housekeeper, who was most likely Mrs. Cleon. "I am Miss Manners, of Boston, to see my cousin, Mrs. Sophronia Hatchet."

"By Gawd," the woman muttered. "Look at you."

"Evening then, Miz Sophronia." Cleon slouched his hat at the frizzled creature. "Found 'er up the beach, just like you said I ought," he confirmed, as if Marigold were a stray cat he'd happened upon. "Rowed us here, she did, poor Esmie's girl. Took the oars, straight off—t'were like she knew the way." He rolled his eyes to the pitch-dark sky. "Powerful eerie it were."

"Nonsense." Marigold might have been shocked to find this crone was her mother's cousin, but she would give no sway to old Cleon's ridiculously ominous talk. "It was simple enough navigation to point the bow at the island," she suggested more reasonably than she felt, clenching her fists around the handles of her luggage in defiance of her blisters. "I rowed crew at Wellesley College, you see."

But she took the next moment to remove her hat and veil and recover some of her aplomb before she stepped closer into the circle of lamplight. "Good evening, Cousin Sophronia. I'm your cousin Esm é 's daughter, Marigold Manners."

"My Gawd above," the old woman whispered as she held her lantern higher and reached out a shaking, talon-like hand toward Marigold's cheek. "Of course she called you Marigold."

Marigold felt just the whisper of cold caress against her skin before she flinched away in revulsion. Which wasn't at all like her—normally, she had complete control over both her emotions and actions. "Yes, ma'am, she did."

"You're the spit of him, you are," Sophronia muttered, "with Black Harry's coloring."

"Black Harry? Do you mean my father?" While Harry Manners might not have been the most sterling of characters—gamblers rarely were—Marigold had never heard him referred to in such damning tones.

"Black hair, black eyes, dark as the devil, wicked as sin." Cousin Sophronia continued to mutter under her breath as if she were talking to herself and not her new-met niece. "Sinner he was—you could see it from the day he set his eyes on …" Her voice faded to a whisper. "Only a matter of time before doom devoured them both."

While Marigold might have been estranged from her parents for her own differences of opinion about education and their erratic style of living, she would not stand by while a comparative stranger tarred their good names so blackly.

"I should like it known that my parents were not devoured but passed away from the influenza epidemic that has swept up the globe. It was the highly transmissible disease, coupled with a lack of care"—they had fallen ill from the grippe in a hotel suite far from home—"and nutrition"—their condition had been exacerbated by their decided preference for dry gin cocktails over foodstuffs—"and not any defect of their souls, which were, as should be, entirely their own business and nobody else's."

And while she was on the topic—"I hope to find that you take the usual sanitary precautions here, against such agents of disease as influenza?" Marigold looked at the rust-rimmed pump some distance across the littered dooryard and resigned herself to only rudimentary plumbing. But even with plumbing, the scope for sanative improvement was vast. "I have some experience in implementing a scrupulous system of hygiene." Her Wellesley College coursework in the sciences had been as practical and extensive as her physical education.

Cousin Sophronia looked at her as if any idea of sciences were quite beyond her. "Best take you up before the night falls upon us like sin," she intoned with a narrow-eyed look at the sky.

Another involuntary shiver crept up Marigold's spine to the back of her neck. "We left my luggage back at the beach—"

"Hired girl'll get those." Cousin Sophronia gestured across the yard, where a young Black woman reluctantly stepped into the light. "Leave t'others here. You're not to lift a hand for Hatchets."

"Thank you." Marigold was relieved to set down her bags.

"Best come along then, Esmie's girl"—the woman beckoned her into the unlit house—"before the night creatures get the scent of you on the wind."

With such a dire warning—wolves at the door took on an entirely new meaning—Marigold did not need to be asked twice, though good manners dictated she wait for her cousin to precede her through the uneven entrance and wait in the drafty dark of the hall while the woman laboriously shut the creaking door behind her.

"What about the others?" Marigold thought there might have been other people besides the hired girl in the dooryard, but it had been too dark to make out their features.

"They're on their own, each to find their own way. That's how it is at Hatchet Farm." The heavy wrought-iron latch fell with an ominous clack. "Each to fend for themselves."

The interior of the house was fitted with the same chipped shiplap as the exterior. The peeling posts holding up the stairway and doorjambs seemed to be listing like drunken sailors. Marigold peered up the steep, narrow staircase into the inky, cobwebbed rafters of the place, looking for some sign of warmth or comfort. Or gaslight.

There was none.

Isabella's warning against the primitive came swiftly to mind, but it was far too late to heed her words now.

"You're here at last." Cousin Sophronia picked up a tarnished oil lamp that couldn't hope to dispel the gloom of the dim interior. "Just as I always saw. Just as I knew you should be. Welcome, poor girl, home to Great Misery."

Fullepub

Fullepub