Chapter 5 Liana

"Mom!" Liana turned on Deb as soon as they had reached the safety of the car. "Why didn't you tell me that James Alonso was the class instructor?"

"I figured it wouldn't be a big deal," said Deb, though she shifted uncomfortably. "You're both adults. It's been years since you saw each other. You two kind of circled each other in high school, but as far as I knew, you never really interacted. I thought you didn't really know each other that well."

"We didn't — we don't," Liana said quickly. "But if it wasn't a big deal, why not tell me?"

Deb had the good sense to look sheepish. "Well, I was so excited that you were leaving the house, and to exercise no less, that I didn't want to give you a reason not to come. I was afraid you'd decide to stay home if I told you James was the teacher."

"You're right about that. I would have stayed home." Liana buried her face in her hands. "I can't believe he saw me," she groaned. "What if he'd asked me about my job, Mom? My supposedly big-shot Hollywood career? Oh God — what if he'd asked me if I had a boyfriend?"

"Did he?" Deb asked, suddenly looking far too interested.

"No," Liana said, although she wasn't entirely sure that was true. "But that's not the point. The point is that you should tell me these things!"

"Well, I think it all worked out just fine. Besides," her mom waggled her brows, "I saw the way you two were talking after class. You and James had a moment! He likes you! I can see it!"

"Calm down, Mom. We did not have a moment. He was complimenting me on surviving my first class. That's all."

"Pssh," her mom replied. "I know what I saw. He's interested in you."

Liana shook her head but said nothing. Internally, though, she was reeling. James Alonso! James fucking Alonso, Pine Heights School prom king and all-around golden boy, had asked her out! If only her high-school self could see her now! Sixteen-year-old Liana would keel over dead.

She still didn't entirely understand why he'd asked her to dinner. She'd assumed he meant it as a date, but maybe she was just making assumptions. After all, the James Alonso she knew from high school would never have asked her out. She wasn't unpopular, per se, but she certainly didn't run in the same circle as James and his equally beautiful girlfriend, Mary Grace. In fact, as far as Liana knew, James and Mary Grace were still together. A few months ago, the high school sweethearts were happily celebrating nine years together. She'd assumed engagement photos would follow soon.

James wasn't wearing a wedding ring during today's lesson, but that didn't mean he and Mary Grace weren't still dating, or possibly even engaged. If he were still in a relationship, Liana reasoned, he probably wouldn't ask her out. But maybe she'd read the situation wrong, and he'd simply wanted to grab a meal as two high school sort-of-friends who hadn't seen each other in eight years?

Yes, that was far more likely than any sort of romantic meaning behind his question. James probably wanted to hear about the post-high school life of the Pine Heights valedictorian. Maybe he even hoped to get some dirt on her to bring back to Mary Grace.

Liana thought Mary Grace would probably rejoice at the downfall of her so-called academic rival, a title Liana had never bought into. Mary Grace had made it known to anyone who would listen that she "called BS" when Liana was declared valedictorian. The valedictorian title was given to the graduating senior with the highest GPA. The principal announced that Liana had their class' top grades, with Mary Grace second by 0.01 points.

The principal had meant the announcement as a way to celebrate both Liana and Mary Grace, saying how proud he was that two females were top of their class, but Mary Grace went into a rage. Mary Grace insisted that Liana's mom, being a teacher at the school, had somehow manipulated GPAs to ensure her daughter came out on top. Whenever Liana walked by Mary Grace in the hall after the valedictorian was announced, Mary Grace shouted taunts and asked if Liana was going to go cry to mommy.

Liana never thought her mom influenced how teachers looked at her, but she tried to see things from Mary Grace's perspective and imagined that she'd be upset at any perceived unfair advantage. But Liana still couldn't quite understand Mary Grace's resentment. Sure, Liana was valedictorian, but she and Mary Grace had both gotten into their dream colleges. What did a useless title and a graduation speech matter, especially when Mary Grace had already given a (far too lengthy) speech to their classmates upon accepting her crown at prom?

Mary Grace was beautiful, popular, and dating the equally beautiful and popular prom king. Plus, her family was uber-wealthy, all but guaranteeing her a good job after college through family connections. Liana could claim none of those things. Wasn't it pretty clear that if there were a competition to "win" at high school, then by any measurement, Mary Grace had won?

Liana had to admit that James had never seemed to buy into the academic rivalry stuff, shutting down his girlfriend every time she heard them talking about her. James had been nothing but gentlemanly during high school. Still, it was one thing to shut down false rumors Mary Grace instigated, but another thing entirely to ask Liana on a date. She had to have misread the situation.

"Liana," Deb said gently. "He's a nice boy. And it wouldn't be the worst thing in the world for you to try dating again. They won't all be like Oliver."

"I need to focus on my recovery before I can think about dating."

"Nonsense. If you're well enough to attend an exercise class, then you're well enough to go on a date."

"Nobody is going to want to go on a second date with me once they realize I can't do anything fun. Plus, most first dates are at a bar. You know I can't drink."

"Lots of people don't drink," her mom reasoned, "and anyone who thinks drinking is a requirement for a date is someone you don't want long-term, anyway."

"It's not that I can't drink. I can't eat. What am I going to do: insist that every date be at a coffee shop only? I can't get dinner, can't get lunch. I can't get a damn acai bowl. I can't even go to a movie and split a bucket of popcorn. I can't go to a baseball game because I can't go four hours without eating, and I sure as hell can't eat some peanuts or a hot dog."

"Oh, my baby," said her mom sorrowfully. "You know that anyone worthy of you will understand. You're not one of those crazy Hollywood types who only drink green juice by choice. You have a lifelong medical condition. It's not like you're making things up."

"I know," Liana sighed, and she knew that both she and her mom were remembering the last few years, before Liana had received her Crohn's disease diagnosis, when Liana was convinced that the symptoms she felt were "all in her head."

◆◆◆

Liana had always struggled with anxiety, especially in college. When the pandemic hit, and Liana had to attend online school from her childhood bedroom, she assumed that her increasingly poor physical health symptoms were manifestations of her anxiety. The mind-body connection was real, right? And wasn't everyone experiencing anxiety during lockdown? So it stood to reason that her near-everyday stomach pain and occasional vomiting could be symptoms of her already-diagnosed anxiety.

One night early in the pandemic, Liana found herself unable to stop vomiting for fourteen hours straight. Her mom found her hunched over the toilet, clutching a sharp pain in her upper abdomen.

Liana had reluctantly allowed her mom to take her to the emergency room, where the lobby medical assistant took her temperature and eyed her skeptically when she was a perfect 98.6 degrees. In those early COVID days, nurses used temperature to sort patients. The attendant told Liana she probably did not have COVID and gestured for her to sit and wait until a doctor could see her.

Liana puked into a bag for nine hours in the emergency room lobby, waiting as person after person suspected of having COVID was taken into the hospital before she was. Finally, long after Liana had stopped having liquids in her stomach to vomit, the doctor saw her and declared that she likely had a burst ovarian cyst. A technician stuck a probe up her vagina for an intravaginal ultrasound, which revealed scant evidence of any cyst.

"It happens a lot," the doctor told her, "when the cysts abrupts, it doesn't leave much behind." He gave her an IV of Zofran to stop the vomiting and some fluids to rehydrate her. Once she'd successfully eaten one soda cracker, he sent her on her way and advised her to make an appointment with her obgyn, but assured her there would be no lasting effects from the cyst.

The next time Liana had acute stomach pain, three months later, she didn't bother to see a doctor. If it were just a cyst, the doctor couldn't do anything to help her, and it wasn't worth the trouble. Plus, hospitals were overflowing, and she didn't want to take a bed away from a COVID patient who needed it. She was young, in her early twenties, and it was selfish to demand a doctor's attention when the elderly and those with respiratory problems couldn't even get into a hospital.

By the third time she had an attack of vomiting and stomach pain, Liana had stopped believing she had ovarian cysts. So she went down the WebMD rabbit hole, trying to determine if food could be exacerbating her anxiety. After all, it seemed that if she simply didn't eat, she felt fine. She realized that every time she'd had stomach pain in the past few years, it only occurred after eating. Perhaps she was eating the wrong foods. There must be a "healthier" diet that would make her digestive system work right again.

The anti-inflammatory diet seemed to fit the bill. Liana spent hours driving to grocery stores, trying to find the right combination of fresh fruit and vegetables and legumes. But after months of following the anti-inflammatory diet strictly, she found her stomach pain steadily increasing each day.

More googling. Perhaps her anxiety was causing IBS? If so, a diet she found called FODMAP would surely make her feel better. But after a carefully prepared meal of soba noodles sauteed with arugula, bell peppers, and almonds — all on the FODMAP diet — Liana found herself once again vomiting in the emergency room, fearing that her stomach was about to burst. This time, she was screened for appendicitis, but her appendix was intact.

Liana decided to see a gastroenterologist, who assured her that IBS as a result of anxiety was very common. Was Liana sure that she had her anxiety under control? Yes, Liana told the GI honestly, her anxiety was very much under control. By that point, Liana was the happiest she could remember being in a long time. She'd ended up enjoying the time spent at home, relaxing with her mom; she was weeks away from graduating college and poised to move to Los Angeles to try to start a career making movies; and she'd received her first COVID vaccine, making the world feel new and inviting again.

The GI gave Liana a side-eye, seeming to doubt that Liana's anxiety was under control. But he agreed to run a full abdominal ultrasound to rule out diseases.

The only irregularity that the ultrasound revealed was a swollen liver. The GI told Liana she had fatty liver disease. "Unusual," the doctor said, "given that you're underweight. But not impossible, especially if you have diabetes."

Multiple subsequent tests revealed that Liana did not have diabetes. "Fatty liver disease, then," the GI said, and gave her a pamphlet on a high-fiber diet. Fibrous foods such as beans and leafy greens would do wonders, he said, as would avoiding simple carbohydrates like white bread.

Liana tucked the pamphlet into a box as she packed up her life for her long-planned cross-country move to the West Coast. Liana and her mom took five leisurely days to drive from Miami to Liana's new apartment in Hollywood, which she was to share with three other acquaintances from college. All four had dreams of making it big, and Liana felt the excitement run through her each time she saw the Hollywood sign out her window.

Finally, she thought, she'd made it. She had an honors English degree from an Ivy League school and was about to start a highly competitive internship at HBO. Los Angeles was still half shut down due to COVID, but that was all right with her; she was never the most social person in the world, and she preferred sitting on the beach in Santa Monica or driving the curves of Mulholland to clubbing, anyway.

Liana was convinced that, with her GI's food advice in hand and her anxiety nearly nonexistent, her health challenges were finally behind her. She was 22 and in L.A. working at HBO — what a dream! But the next year was hell. Liana awoke each day excited, only to find herself in pain each night by 8 pm. She found herself gradually refusing any and all social invitations.

Each day, she was convinced that she just wasn't following her diet closely enough. Hadn't she eaten strawberries yesterday? Those were high-fiber, but they also had carbs, and weren't carbs evil? Yes, the solution must be to cut out all carbs.

By the one-year anniversary of her move to L.A., Liana had an epiphany. When she didn't eat, she didn't feel sick. So there was a simple solution: she would just stop eating.

She decided that she would survive mostly on a liquid diet of chicken broth and vegetable broth, with the occasional juice or smoothie to give her body some nutrients. She would allow herself a bare minimum of solid food to try to make the diet sustainable long-term: 800 calories per day of solid food, eaten in increments of 200 calories apiece every four hours. (Eating too much at a time seemed to be a consistent cause of stomach pain.) Most of her solid meals would consist of white bread, white rice, or peeled potatoes — the only three foods she found that never seemed to cause her pain, unless she ate too much of them at a time.

The diet worked — at least in one aspect. Liana no longer had what she called the "attacks," those hours-long fits of 10-out-of-10 stomach pain and vomiting.

But try as she might, Liana couldn't recover her health. In fact, even as her acute symptoms improved, her overall health declined. She felt constantly fatigued. Her brain felt sluggish each day, shrouded in a fog she couldn't escape. Even worse, she found that her brain-fog was affecting her career prospects. By that time, the HBO internship had ended. After applying unsuccessfully for dozens of jobs, she took a job in a studio mailroom, which many people had told her was a common path to success.

But in order to move up from the mailroom, Liana soon realized she had to schmooze. That meant happy hours every night, not to mention working lunches and being seen at the right parties. Liana was an introvert, and while that didn't mean she was incapable of social events, going out was draining. She liked happy hours generally — especially when her producer idols attended them — but she needed a lot of energy to put herself out there in the best of times. Given Liana's constant fatigue and stomach pain, she simply didn't have the energy to attend the necessary happy hours and social gatherings. She also felt extremely self-conscious about having to avoid alcohol and most foods.

If she couldn't attend after-work events, she resolved to be as social as possible during working hours. But she couldn't quite push herself to network as much as she should. She knew, on an intellectual level, that she was far from her best at work, her brain as deprived of calories as it was. Her mind betrayed her by loving her size-zero figure, but Liana knew that starving herself was probably costing her a good shot at a job. Still, she couldn't make herself eat, and she resolved to continue to look for work while eating the bare minimum calories to maintain a somewhat intelligible conversation with a potential employer.

Desperate to make rent, Liana took a position with a smaller studio. The gig sounded somewhat exciting, despite the below-market pay and the fact that it was a contract position.

Finally working fulltime and unwilling to lose her job because her brain was starved of calories, Liana forced down small meals. But as soon as she started giving herself enough calories to function mentally, the excruciating stomach pains started again. And paradoxically, even as she was eating more, she became more and more tired each day, especially by the end of the day. She left the office promptly at 5:30 pm each night, desperate just to make it home and collapse into her bed by 6:30.

Her contract position afforded her no health benefits, but at age 24 Liana was luckily able to use her mom's health insurance. She decided to try a different GI. After describing her symptoms of stomach upset, upper abdominal pain, and acid reflux, the GI told Liana she surely had an esophagus or stomach condition. An upper endoscopy followed, which also failed to uncover any medical diagnosis.

For the next few months, Liana hardly had time to work, much less schmooze, as she dutifully underwent dozens of tests to solve her medical mystery. At her doctors' urging, she took obscure medical tests that sounded like things out of a sci-fi novel. She swallowed a radioactive pill and held a scanning machine to her body as it passed through her digestive tract. She had more than 20 different blood draws. Multiple imaging scans. Another nuclear test, this time eating a radioactive egg-and-jam sandwich. All inconclusive. Nothing abnormal. When she wasn't avoiding eating, she was fasting per doctors' orders in advance of some medical procedure or another.

Her health worsened. I must be subconsciously anxious about work, Liana thought. I don't think my anxiety is bad right now, but what do I know?

Finally, this past summer heralded a breakthrough. A super-niche GI specialist thought to do a colonoscopy: a basic, regular procedure for anyone over 50, regardless of their health, but a procedure no one had thought to perform for Liana.

Liana still remembered the doctor approaching her, in her post-colonoscopy anesthetic drug-induced haze: "I think you have Crohn's disease." When the drug fog cleared, Liana thought she must have heard wrong. Wasn't Crohn's a disease where you had diarrhea several times per day? She'd never had diarrhea once throughout her years of sickness, not that she liked thinking about those kinds of things.

But sure enough, an MRI and a couple of additional tests confirmed an advanced case of Crohn's disease, an autoimmune disorder. Essentially, Liana's digestive system was hyperactive, attacking itself. Her bowels had been chronically inflamed for years, to the point that she had multiple layers of scar tissue all down her intestines and was no longer able to absorb most nutrients. Plus, all of that scar tissue had piled up on itself, to the point that Liana's small intestine had about 1% of the area of a normal person's. No foods could pass through Liana's intestines, causing the blockages that triggered vomiting.

All of Liana's diets — and especially past doctors' suggestions to increase her fiber intake — had accelerated the disease's progression. Fibrous foods, especially the kale and beans Liana had favored, caused Liana's immune system to attack itself constantly. Counterintuitively, simple carbohydrates would probably have been better for her Crohn's disease than foods commonly thought of as "healthy," like raw vegetables and fibrous fruits. Liana had stumbled upon a Crohn's disease diet by chance through experimentation: broths, chicken, eggs, and potatoes were commonly recommended Crohn's-friendly foods. Still, Liana's years of food trial and error had caused her disease to progress quite rapidly.

The doctor told Liana gently not only that she should start on immunosuppressive drugs, but also that she probably needed surgery. There was no way to get rid of Liana's intestinal scar tissue other than to cut it out. The human body had about two meters' worth of intestines, and by removing 50 or 100 centimeters of diseased area, Liana might be able to eat normally again.

Liana was overwhelmed: finally, a diagnosis of a real disease; she wasn't crazy. But the disease wasn't anything she had on her radar. Her research had failed her, and her wild goose chases had taken years of her life. And she might have to have surgery?

The week after her diagnosis, Liana went to the hospital to receive an IV infusion of her first dose of immunosuppressive drugs. The drugs were supposed to keep Liana's digestive system from becoming inflamed. She was told they only made an impact over time — months, a year even. She tried to temper her expectations, sitting in a long row of hospital chairs with dozens of people fifty or sixty years her senior, everyone besides her getting chemotherapy. She listened to their soft-spoken stories of their grandchildren as she tried to work on her laptop.

Driving back to her apartment from the hospital, Liana's boss called to tell her that the company was significantly downsizing and cutting all contractors, including her. Liana's boss offered to put in glowing recommendations for Liana at other studios. Liana thanked him but said that wouldn't be necessary. She'd realized she was simply unable to work full-time in her current state and didn't have the hustle the movie business required. Crying in her room that night, Liana couldn't see any path forward for her in L.A.

Just as she had during the first week of the pandemic, Liana found herself again packing her life into boxes and flying home to Miami, where she again moved into her childhood bedroom in her mom's duplex. Liana was so physically weak that she couldn't walk up the stairs to the second-story bedroom without pulling herself up using the staircase handrail. It took her two weeks to unpack her measly four boxes and one suitcase, because she couldn't walk around for more than five minutes without lying down to rest. She wasn't yet feeling any effects from her immunosuppressants. That was normal, her doctor assured her.

Unable to fathom the energy it would take to look for a job, Liana spent her days sleeping and trying not to eat. After exhausting other options, Liana decided she felt so terrible that she should try the intestinal removal surgery.

She and her mom decided to schedule Liana's surgery for November, two months before Liana's birthday, so that Liana would still be 25 and therefore able to use her mom's health insurance. Liana spent the entire Thanksgiving week in the hospital, trying to convince herself that the drip, drip, drip of the IV was her new beginning. She was discharged six days after her surgery and spent the following weeks recovering at home.

In January, just before her 26th birthday, Liana was given the go-ahead by her surgeon to resume normal activities, including driving and light exercise without abdominal strain.

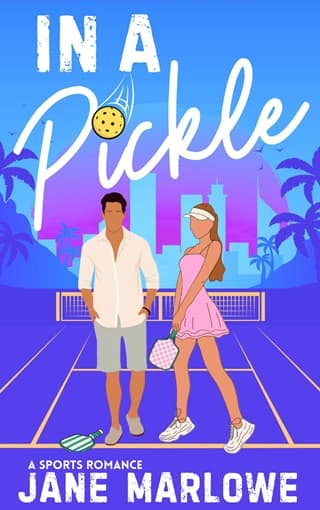

Now, in February, Liana was spending her days looking for a job, trying not to spiral into the hopelessness that had dominated her life for the last few years. She was also, apparently, attending a one-a-week pickleball class.

And there it was: the story of the downfall of Liana Abrams. The high school valedictorian and Ivy League grad who had a bright future ahead of her; everyone had always told her so. But oh, did she prove them wrong. She was washed out by 26, an utter failure, unemployed and living at home without any job prospects or the ability to walk a mile.

◆◆◆

"Where did you go?" Deb asked, pulling Liana out of her reverie in the car. And then, more softly, Deb added, "One day at a time, right? One thing at a time, Liana. You're here. You're recovering. You're doing great, sweetie."

"Thanks, Mom." She tried to believe her mom's words.

"What's your plan for the rest of the day? I'm planning to make chicken soup if you'll be home for dinner."

"I will be home, and chicken soup sounds delicious. Thanks, Mom. I'm just going to send out more job applications," Liana replied. And try not to think about James Alonso.

Fullepub

Fullepub