Forty-Three

Max sat in the dark with his magnum opus, the culmination of his life's work, the sum of his artistic ambition as a horror creator.

On the silver screen, the players frolicked and fought their petty squabbles, beautiful and larger-than-life, brimming with youth and dreams, unaware they were all doomed to die horribly. An ancient mythic script now rendered in history's most wonderful optical illusion, the product of persistence of vision when viewing a series of images flashing by at a high rate. In this case, film recorded at twenty-four frames per second and played back at the fusion frequency of forty-eight hertz. The science and magic of cinema, rooted in humble beginnings in the zoetrope and cartoon flip-books, on to Edison and Dickson and all the way to the slasher flick and horror's final incarnation: If Wishes Could Kill.

By buying a ticket, the audience had summoned the players back to life like reanimated souls haunting a stretch of film. The living sat stacked behind him, they and the whole human race, all of them playing out their own dramas, similarly doomed. Each of them alone but also not alone. The screen the campfire, the movie a story about survival, the surrounding darkness filled with predators that still lived in the genes. They'd come for horror, a psychological room where they could share and face their collective fears, traumas, and taboos—both the rational and mundane kinds inflicted by the current zeitgeist and the illogical kind lurking deep in the soul. And feeding these fears, there were the horror creators like Max, inch by bloody inch carving out new spaces promising fresh scares and thrills.

He'd certainly faced his own fear. The horror of seeing his father drop dead at the dinner table after telling a joke. A moment demanding endless repetition and awe. At last, in creating Wishes and dying for it himself, in being reborn into this loveless and fearless afterlife, he'd vanquished his lifelong trauma.

Even if he weren't dead, he'd have no regrets. Not a one. Max had gained what Hollywood's storytellers would call a positive character arc, where the protagonist gets exactly what he needs and becomes a complete person.

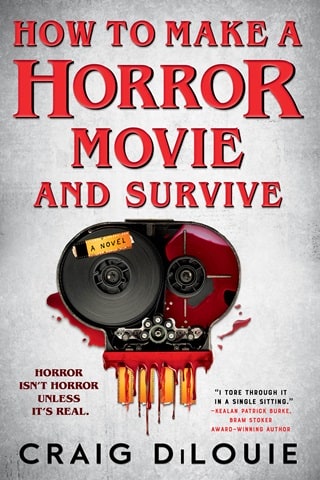

He'd made the perfect horror movie.

The cherry crowning a long, venerable history of horror cinema. From the experimental early shorts exploring the medium's innate strangeness to the silent horror films, flicker and shadow, murky and ominously mute, which led to the dreamy desolation of German Expressionism following the Great War. Universal Studios birthing the monsters of the Great Depression in the thirties, from Dracula to Frankenstein, making horror less artistic and more accessible until the horror-comedies of the forties and the next innovation: psychological horror. On to the mutant monsters of the atomic fifties, the psychos and witchcraft of the psychedelic sixties, and the closer-to-home terrors of the paranoid seventies. Right up to the romping eighties with its slashers and seemingly everything else on the menu.

One could read the dark and stormy history of the twentieth-century American psyche in these films, which like bad dreams purged the nation's lusts and fantasies and paranoias and collective fears. All of it led up to tonight, this movie, where the story was real and the real was story and you were a part of it. Where reality and fiction rutted to become a surreal waking nightmare, a nearly two-hour night terror, a psychic tattoo you'd carry with you forever like a liminal STD. What you are about to see is real, viewer discretion advised.

And he was the visionary who'd made it.

Max sighed. He wanted nothing.

He was done.

When Jim Foster disappeared in the glare of a truck's headlights, the crowd sucked in its breath. A reverent pin-drop silence fell upon the theater, a tangible church hush, so quiet the dead heard the rattle in the projector booth and the living the blood rushing in their ears. When the climax kicked off with Johnny Frampton impaling himself, a few broke down sobbing.

Do you see now?he thought. Do you understand horror the way I do? His audience had just witnessed, close-up and personal, real death in all its drab and startling pageantry. Surely, they comprehended the awful respect horror demanded, the delicious pain it delivered, now that it had displayed its full power.

The camera lingered on Johnny's bleeding corpse, the bag of Lay's Italian Cheese Potato Chips partially visible in the corner of the frame.

"Yum," someone called out, provoking a wave of nervous chuckling.

Yeah, okay, thought Max.

They laughed because they were scared, he knew that. They were young and didn't think they'd ever die. They laughed at death.

He still didn't like it. They could laugh at eternity and try to fill it up with wishes all they wanted, but Max demanded they gaze into the void.

As if powered by its bleakness, the movie inexorably carried on toward the next death. The camera jerking and wobbling in a dizzy abandonment of convention, the sound ranging from terrible to nonexistent, the abrupt disregard for production quality practically breaking the fourth wall. It only made the movie grittier. The real even realer. As if the movie no longer cared if you watched, and if you looked away, if you so much as blinked, you might miss what was coming.

Max turned in his seat and scanned the gawking teen faces shining in the movie glow. Kids who used to be his core audience. They were riveted, but he could tell that jokey yum and giggle had broken the spell. It's only a movie, they thought. They could at last breathe again, clutching their oversize Cokes and crunching their nonpareils and dipping into their greasy tubs of popcorn. Many were too young to be here in the first place, but an X rating didn't stop these boys and girls from taboo. One trope the horror movies always nailed on the head: Tell a bunch of teenagers something is forbidden, and they'll run a race right at it.

Grumbling, Max crossed his arms and sank deeper into his seat.

The next death struck like a bullet: Bill Farmstead's head popped off to produce a collective whoa that came out an anguished empathetic groan. Holy shit, someone yelled, which produced another smatter of anxious chuckles. To Max's utter delight, at least half the audience stood and fled the theater. Among those who stayed, however, the chuckling became general, took on an angry note of defiance.

When the jet engine tumbled out of the darkness to plow Ashlee in a vast wave of dirt, a group of boys cheered from the back row.

"No," Max said.

"Do you hear that, Nicky?" Ashlee called out in the dark. "They love me!"

With her spectacular on-screen demise, the atmosphere changed, a subtle shift in the power dynamic. A few more moviegoers trickled out, but the remainder stubbornly held on. The heavy despair and constant on-edge nausea and terror dissipated. Some had seen the film several times and shouted out lines, turning If Wishes Could Kill into an impromptu Rocky Horror Picture Show.

"Quit that," Max snarled. "Shut up!"

As if in defiance, the audience roared louder, braying like hyenas. His cast got into the act, cheering their on-screen deaths. Even the thickening darkness in the theater, the presence Raphael called the Beast, powerful and intangible as Hollywood, chortled along with them.

"Stop it!"

Jordan tilted his head. "You're talking over your own movie."

"They're laughing again."

"They're surviving, babe," the producer said. "It's called proof of life."

On-screen, Max told Sally he loved her and disappeared into the earth. Gales of laughter filled the theater.

"What have I done?"

Jordan smiled behind a puff of cigar smoke.

"You raised the standard, killer. I salute your genius."

Max howled into the flicker.

Horror wasn't horror unless it was real.

Fullepub

Fullepub