Chapter 99

The first thing I noticed when I arrived back in Sydney at my mother’s house was that the Madame Mae sign had gone from the letterbox. I had been so embarrassed about that sign, before I came to accept it, and then, it seems, I’d apparently become proud, because I felt such a sense of loss when it was gone. Now our house was just ordinary, no different from anyone else’s in our street. We were no longer special.

Auntie Pat opened the door. She had moved into my old bedroom. I wasn’t aware of this.

Mum was up and dressed, but she carried herself carefully like someone in pain, although she insisted she wasn’t feeling any. Her face was gaunt, but she was smiling, her eyes shiny with happiness to see me.

The last time I’d been home had been for Ivy’s wedding (to my wedding photographer, I was her bridesmaid and was very careful with my bouquet and did not leave a pollen stain on her wedding dress). Mum had been slender then, but I’d been pleased for her, I’d thought it was all the dieting paying off. Now she was fragile and birdlike, her clothes hung off her, her cheeks were sunken and her eyes enormous. Still beautiful but terrifyingly frail. We’d been the same height and build for many years, but our hugs had always been of a parent and child. I had always leaned toward her. Now for the first time it was as though I was taking her in my arms.

Before I could express my concerns, she stood back and surveyed me and said, “You look terrible.”

Auntie Pat said, “Yes, you do.”

“It’s a long flight,” I said defensively. I was not the one who looked terrible!

“What’s wrong with you?” demanded my mother, sounding not at all frail.

I didn’t tell them about the Friday-night parties, or the way my thumping heart woke me in the middle of the night with a gasp of terror, or about my permanently dry, sour mouth and the dull feeling in my head that only went away with my first drink each evening.

I told them I was distressed because we had learned that David and I couldn’t have a baby. I didn’t tell them of my secret relief, and I didn’t tell them I needed a baby to save me and my marriage from the dreadful abyss into which we seemed to be falling.

It turned out this was old news. David had called his mother and Michelle had called Mum.

David would have been just thrilled to know his mother and his in-laws had been discussing his sperm.

(He would not have been thrilled.)

They said it was going to be fine. Michelle had a plan, which she wanted to discuss with me, and Mum and Auntie Pat were already on board. David and I were to be brought on board too. The plan was that we would adopt a Korean baby, and our baby would be so very lucky, because unlike most adoptees going to white families, he or she would have a Korean grandmother and a half-Korean father. Michelle had already been calling adoption agencies. Auntie Pat was waiting to hear back from a friend whose daughter had adopted a baby from Korea, in case she had useful information. Mum had various distinguished people writing character references for us: the mayor, my high school principal, the head of the local chamber of commerce. (They had all sat for her at various points.) Of course, these references were probably not even necessary; David was not only half Korean but had a career in cardiology, saving lives, while I worked for the Australian Taxation Office, helping catch tax avoiders. We were clearly of excellent character and would go straight to the top of any list of desperate parents-to-be.

The mention of excellent character recalled a vision of our behavior at the rooftop parties, hands all over each other, in full view of everyone, staggering down the stairs to bed. It felt sensual at the time but so sleazy and vulgar in the morning, and reprehensible in my childhood home. What would my dad think? What would Jack think? I could not imagine either of them on that rooftop. Sometimes I wondered if my recurring image of two people toppling backward into the inky black night was symbolic. It represented David and me, but I only thought that when I was drunk; when I was hungover I had no interest in symbols or visions and I knew it meant nothing.

“Obviously this is only if you and David are happy with the idea,” said Auntie Pat.

“Really?” I said. “We have a choice in the matter? We won’t come home one day and find a little Korean baby on the doorstep delivered by the postman?”

“Very funny,” said Auntie Pat.

“Didn’t that happen to Betty Carroll?” said Mum.

“Betty’s baby didn’t come from Korea, Mae,” said Auntie Pat.

(It was an open secret nobody was really bothering to keep anymore. The oldest Carroll girl, Bridgette, had given birth at fifteen to the fattest baby you’ve ever seen.)

“Oh, yes,” said Mum. “Fancy me forgetting that.” She frowned. “I think I predicted it too.”

Another woman might have found it outrageous that Michelle was already making calls to adoption agencies on our behalf, but Iliked the idea of pleasing my mother-in-law, and—this sounds terrible—I think it reduced my level of responsibility. If I couldn’t take care of this baby Michelle was organizing, she would do it for me. She would help me keep the baby alive, and the baby would get me back into my clotted-cream house, where all my fancy dinnerware and wedding boxes were packed away along with my former self, while another newlywed couple paid us rent to live there. Also, I would be doing something “good” by helping out a child in need.

“I think I would like to adopt,” I said. “If David is happy to.”

Of course, we didn’t know what we didn’t know. We didn’t know many of the Korean children adopted at this time were not orphans at all. We didn’t know about unwed mothers being coerced into giving up their babies, or document fraud, or profit-driven adoption agencies. It did not occur to us to think about distressing questions of identity that might face these children when they grew up.

I watched Mum tentatively nibble a tiny corner of lamington as if it were a strange exotic food rather than her favorite cake, then put it back on her plate with a deep sigh of resignation.

I slapped my palms on the table and said there would be no more baby talk. We needed to focus on Mum and her health. This, after all, was the purpose of my visit. I said it was ridiculous that she hadn’t been to the doctor yet, and Mum said, no need to get bossy, Cherry, because she’d been yesterday! Pat had finally worn her down.

Mum looked so pleased with herself. She was experiencing the glorious relief of having faced a fear. She’d believed going to the doctor would make her sick, but now she’d finally been convinced to go, she was convinced it would cure her. Sillier things have been thought.

They were waiting for a whole lot of test results. The doctor was being extra cautious. She probably just needed an antibiotic!

Auntie Pat avoided my eyes. I said, “I thought you read your own cards and you’re going to die?”

She said, “Oh, we’re all going to die, Cherry. I probably misinterpreted it. I am human, after all.”

I asked about the Madame Mae sign and Mum said she’d taken early retirement. It had started to become too tiring. Sometimes she’d been so tired she saw nothing, nothing at all, and she had to make it up. She said this as if we’d be shocked. Once again Auntie Pat and I pointedly avoided eye contact. Didn’t she make it all up?

“All these women, looking at me with such need in their eyes, year after year,” said Mum. “I couldn’t take it anymore. Some of them became too dependent on me. They got addicted. That woman from the Southern Highlands wanted a weekly appointment. I said, absolutely not, you can come twice a year at the most. She wore me down and I let her book in for quarterly visits, but it just wasn’t…healthy.”

“Why were your customers mostly women?” I wondered.

“Because women are more in touch with their intuition,” suggested my mother.

“Because women have less control over their lives,” said Auntie Pat grimly.

For the previous two months, Mum had been “closing up shop,” telling her regular customers that this would be their last reading with her. She was referring them all to a psychic who had set up an office in the local shopping center next to the dry cleaner. “She’s talented and terribly energetic,” said Mum. “She sees twice as many customers a day as I ever did. Charges twice as much too.”

Mum’s regulars had all brought along gifts to their last appointments: flowers, potted plants, homemade jams. There were cards on display all along Jack’s floating bookshelves with heartfelt handwritten messages: I owe my life to you, Madame Mae…I could not have gotten through these past difficult years…you guided me in my darkest hour…if it wasn’t for you, Madame Mae, I would never have had the courage to chase my dreams.

Reading them, I felt guilty. I knew Mum was successful. I knew Madame Mae was often booked out for months in advance, but I don’t think I had been truly aware of how much she meant to people. This was like the retirement of a beloved teacher, therapist, or priest.

Her last ever reading had been at three o’clock the previous day. Unfortunately it had been with grumpy former bank manager Bill Hanrob, who came once a year, and whenever she said, “How are you, Bill?” he’d say, “You’re the fortune teller, you tell me.” Then he’d chuckle disbelievingly at everything Mum predicted. Every job has its negatives. (Yet he came back. Year after year.)

Tomorrow her office would be dismantled.

“I’m not sure what we’ll do with all the space,” said Mum.

Auntie Pat said nothing, but I could somehow tell she already knew what it would be used for.

“What about one last reading?” I said to Mum. “For me?”

Her face lit up and I wondered if I’d hurt her by never asking for a reading before. I deeply respected her fashion and skincare advice, but had it been disheartening to have so many people consider her an oracle while her own daughter scoffed?

“Yes,” she said. “That’s good. That’s better. My last ever reading will be for Cherry.”

I thought she might just read my tea leaves then and there at the table like she used to do when I was a little girl, but she said she wanted to do it properly. She left the room and came back dressed as Madame Mae: the patterned silk scarf around her head, the heavy eyeliner under her eyes, the dark red lipstick, the cape-like dress.

“Oh, Mae,” said Auntie Pat when she saw her. “You didn’t need to—you will tire yourself.”

Mum ignored her.

“Mrs. Cherry Smith?” she asked in her singsong professional voice, but with a roguish lilt. “Here for your two o’clock appointment? I’m ready for you now.”

“I’m a little nervous,” I said, getting in character. This was something I’d overheard customers say, but I did feel a little nervous.

“No need to be nervous,” said Mum. “All you need to do is relax.”

She pulled back the purple curtain. “Please take a seat,” she said. “Make yourself comfortable. It’s important you are comfortable.” She put a soft gold cushion behind the small of my back.

She switched on the lamps and used a nifty lighter I had never seen before to light the candles as well as a thin bamboo incense stick. The scent of frankincense filled the room. It’s a woody scent, a bit like rosemary, and it helps alleviate anxiety.

She said, “Do you have a preferred method of divination? Tea leaves? Palm? Tarot?”

I said I didn’t mind, and she said in that case, could I please give her a piece of my jewelry, my engagement or wedding ring, for example.

I tugged off both rings and gave them to her, glancing at my naked left hand as I did.

She solemnly placed the rings on a small silver tray on the table next to her. Grandma had given her that tray years ago for Christmas. She’d gotten one for Auntie Pat, too, and said, “You girls can swap if you like,” and I think perhaps they did. It was a strange experience seeing familiar household objects become mystical in this setting and seeing my frustrating, headstrong, beautiful mother through the eyes of a “sitter,” who had maybe caught the train and then walked nervously up Bridge Street, hoping to find answers in this ordinary house made extraordinary because of a little sign hanging from the letterbox.

She asked, “Did you bring a blank cassette for today’s session?”

Then she caught herself. “I have a spare one.” She took one out of a drawer and winked at me as she put it in the cassette player and pressed record. “You may have it for free.”

I didn’t know she offered recordings. It had been so many years since I had eavesdropped. She had gotten so polished and professional.

She sat down, took a deep breath, and said, “Cherry. That’s a beautiful name. It suits you.”

“My mother chose it,” I said. (Being funny.)

“She must be very proud of you.”

We smiled and I thought for a moment I might cry. It’s strange how rarely you sit quietly opposite the people you love, without a menu or a meal or a drink between you.

She said, “Is there anything in particular you’re hoping to learn or explore today, Cherry? A question you want answered? A problem you need solved?”

I thought for a moment and then I said, “Lately, I just don’t seem to feel…happy.”

(All these years later, when I listen to that recording, I hear my voice break on the word “happy.” I’ve had the audio cassette recording transferred to a file I can listen to at any time. I press an arrow and there is my mother’s long-dead voice, as if she is sitting right next to me, as if she is still available on the other end of the phone, and then there is my own voice, which sounds absurdly young, high and shrill, but recognizably me; it’s as though I’m a bad actress, putting on a childish voice, or as if I have sucked on helium gas.)

“I can’t see a future for myself,” I said, “I just see a…big blank space.”

“Is there anything you wish you could see in your future?” asked Mum, but I’m going to call her Madame Mae now, because if I’d told my mother I couldn’t see a future for myself, she would have responded with exasperation and loving mockery: “Oh, you can’t see a future for yourself, Cherry, you poor thing, with your university education and your handsome husband and that diamond ring on your finger.”

I said I just wanted to see happiness in my future. Isn’t that all anyone wants?

“So you need to make some changes,” said Madame Mae.

“What kind of changes?”

“You will know.”

In the recording you hear me shifting about in my seat. “ How will I know?”

I was annoyed, a little contemptuous. It was as I’d always suspected, Madame Mae was simply a mirror, reflecting back whatever her customers so obviously wanted to hear. An untrained therapist who spoke in generalizations.

She said, “Will you close your eyes, please, Cherry.”

Funny how she said my name now, with detachment, as if I were a customer, not her daughter. No more laughing about my mother choosing my beautiful name.

There was silence. I grew impatient. I opened my eyes a fraction, and saw that she had her eyes closed too. She breathed slowly and deeply, my rings now in the palm of her hand. I watched her for a moment and she spoke without opening her eyes. “Please keep your eyes closed and just breathe. That’s all you need to do for the next little while, Cherry. Breathe.”

I obeyed. I breathed slower, still slower, and I began to feel as if I might doze off. I wondered if any of my mother’s customers had nodded off over the years, and what Mum did in those cases; did she clear her throat or nudge them gently with her foot? This silent breathing had also not been part of her routine when I eavesdropped. It felt as though my mother and I, or Madame Mae and I, went into a kind of meditative state.

There is plenty of research showing the efficacy of meditation in lowering blood pressure and reducing stress, and some believe expert meditators access a universal consciousness and therefore develop what could be perceived as psychic abilities. Is that what was going on with my mother that day?

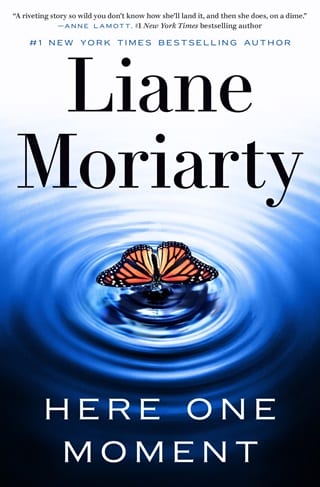

She said, “I see so many things in your future, Cherry, so many beautiful things. They’re all fluttering about me like butterflies, I hardly know where to start.”

Mmmm, I thought skeptically, in my dreamy state. Pick a butterfly, Mum.

“I see you climbing up a mountain trail. Patches of snow. Glinting diamonds in the sunlight, and you see the spires of a castle, and you’re laughing with somebody who makes you happy, and you…oh, that’s gone…let me see…”

“Is it David?” I interrupted. “Is that the person making me happy?”

Do you see me leaving? Do I see me leaving?

“I don’t know.” A pause. “It’s someone you love.”

Another long pause, then she said, this time with confidence, “You’ve already met the love of your life.”

“So you mean David?” I felt relief. It would be convenient for all if my husband was the love of my life.

She paused and when she spoke again, she said, once more, a little uncertainly, “You’ve already met him.”

Could she mean Jack Murphy? But what would be the point of telling me my deceased boyfriend was the love of my life? Didn’t she always say, “They come for hope, Cherry. They should leave feeling happier and lighter than when they walked in my door.” “Lighter in the wallet,” Auntie Pat would say.

“I see a notebook. I see many notebooks.”

“Right,” I said. “I’ll keep an eye out for notebooks.”

In the recording you can hear my impatience. I wish I hadn’t spoken like that.

“It’s important you remember this: a marriage can change in ways you can’t imagine, Cherry.” Was that Mum or Madame Mae? A little acerbic. Could have been either. “You can bring it right back from the brink, if that’s what you both want. And it can get better and better. Honestly. Better than you imagine.”

Back from the brink. I saw again that image of the couple sitting on the edge of our apartment rooftop, backs to inky-black sky, falling into nothing.

“I see you moving, all the time, so much moving.”

“Moving where?”

“Everywhere. On big planes and little planes, a train crossing a ravine over an arched bridge, a gigantic hot air balloon, a tiny car, driving along the coast, singing; I wonder where you’re going? Back and forth, back and forth, here and there, but you’re so happy.”

“I’m going to become a travel guide?” I was being smart.

She said, “I do see a career change, yes. More learning. Late nights. Very, very hard. You will think you can’t do it, but you will do it. You’re very clever. A successful career. A little bit like mine, different from mine, of course, but there is a kind of…similarity. You will say, I’m like my mother, I’m a fortune teller. ”

“Really?”

“It will be a kind of joke. I don’t understand the joke. But I know this career will make you very happy. Proud. Well done, Cherry.”

Her voice became quieter. She was tiring. I opened my eyes again and she looked exhausted, her shoulders slumped, my rings still held loosely in the palm of her hand.

“Will I have a family?” I asked. “Children?”

Another long pause.

She said, “I see a little girl. She will come on a plane.”

That would have been so impressive if she hadn’t already known about the potential adoption.

“She will come. Just when you need her the most. Her first name begins with…”

A long pause.

“It doesn’t really matter, Mum…Madame Mae,” I said. I always found the predicting of initials to be so pointless. A chip on the roulette table. You never know! If they get the initial right, everyone is amazed; if not, no one is that worried.

“ B ,” said Madame Mae. “Her name will begin with the letter B .”

“Wonderful,” I said.

There was another pause, and when she spoke again, her words became garbled. It frightened me. I was worried Auntie Pat would be cross with me for suggesting she give me a reading.

“ The little girl won’t stop the pain, terribleterrible pain nothing like it, IknowIknowIknow hurts so much, it’s unfair, it’s unbearable, can’tstopithurtingdarling…but she will help, she will be a reason to get up, likeyourlittleface gave me a reason, you just need a reason to get up, look for the notebooks, if there is a way, promiseIwillbethere keepbreathing keepbreathing that’s all you can do. ”

She stopped.

Her face looked terribly old. There were beads of sweat on her forehead.

She opened her eyes, shook herself slightly, flicked “Stop” and “Eject” on the cassette recorder, and handed me the tape. She said, “That will be fifty dollars, Mrs. Smith.” Her eyes lost their spooky glaze and she grinned at me. Madame Mae was gone. It was Mum again. “Only joking, you know I always collected payment upfront. Did you find that helpful? Do you feel more hopeful?”

She looks tentative and vulnerable, as well as spent. “I know sometimes people wish I could be more specific, more prescriptive, but that’s not…that’s not the way it works, of course.” There was something so defensive about her, as if I’d come backstage to meet her after a performance.

And was it a performance? That’s what I still didn’t know.

I thought of all the books she had continued to borrow from the library; she’d taken her ongoing professional development requirements as seriously as a chartered accountant. I thought of the times she’d mentioned a new technique she was trying, and how she had always taken half an hour at the end of each working day to write a little reflection, I guess you’d call it, about her day’s work.

“Yes,” I said. “Thank you, Mum. That was wonderful.”

I didn’t know what I felt.

Mum got her test results a few days later. It was not good news, but of course you already know this. We all knew it. She’d left it too late. The silly diets had not been the cause of her digestive problems. The silly diets had masked the true cause.

“Six months,” they said. “A year at the most.”

Fullepub

Fullepub