Chapter 38

People are always intrigued when they learn my mother was a fortune teller.

Like Clark Kent racing into a phone booth and emerging as Superman, she closed her bedroom door and emerged as “Madame Mae.”

Sometimes, in a social situation, a friend will suggest I tell other guests about Madame Mae and I will think, Wait. Is this why I was invited? Am I the entertainment? Is my mother the most interesting thing about me?

Possibly.

That’s how it happened at that dinner party in 1984.

—

We broke into spontaneous applause when our hostess placed an extravagant multilayered lopsided concoction of chocolate flakes, cream, and sour cherries on the table. “It’s a German Black Forest cake,” she said tremulously. I seem to recall someone, I hope it wasn’t me, attempting to amuse by responding in a poor German accent.

Look, it may well have been me.

We all make comments we regret at dinner parties.

The dessert was a triumph. I would go so far as to say it was a defining moment in our hostess’s life. It became her signature dish. I have eaten it many times since then. Her eulogy will undoubtedly reference it.

Her name, by the way, was Hazel.

It still is Hazel!

She needs to watch her cholesterol but is otherwise in good health.

We developed a kind of friendship after I became a client at her hairdressing salon, which was called, unimaginatively, Hazel’s Hair. She grew up in the same area as me and went to the same high school, although she was three years younger. We are not “kindred spirits” but that is okay. She is retired now, but still cuts and colors my hair whenever I am in Sydney.

People compliment my hair all the time and I accept those compliments as if they are for me, not for Hazel’s skills. They assume it’s my natural hair color. My natural hair color is gray, but Hazel “tweaks” it ever so slightly. She has a knack for color.

I realized very recently that I have often taken Hazel’s friendship for granted, accepted it like a queen, as if it were my due, just like the compliments on my hair. You may have done the same with a friend. Give that friend of yours a call. If you find their conversation dull, you could always quietly unload the dishwasher at the same time.

Anyhow, Hazel’s dinner party.

It feels like yesterday!

Not really.

I know it wasn’t yesterday. It was a long time ago.

Our moods had improved. The wonderful cake helped, and also a late southerly buster had caused a dramatic drop in temperature, which meant the fan could be turned off and we could all fix our hair. Furthermore, the grain of rice in the bearded man’s teeth had been dislodged, so that was a tremendous relief for all.

The southerly buster led to a discussion about the unreliability of weather forecasters.

“You’d have better luck with a clairvoyant !” Hazel gave me a flamboyant wink, which I pretended not to see.

The bearded man asked if we’d heard of “chaos theory.” I had, but said nothing as I had contributed more than my fair allocation of conversation.

Chaos theory is the idea that a tiny change now can result in a large change later.

It was first observed by a meteorologist modeling a weather sequence. He mistakenly rounded his variables to three decimal places instead of six, and was shocked to discover this tiny change transformed his entire pattern of simulated weather over a two-month period, thereby proving even the most insignificant change in the atmosphere may have a dramatic effect on the weather.

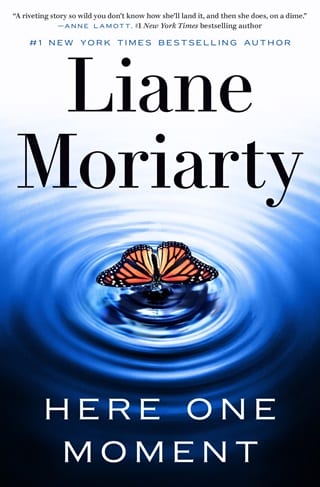

“Could the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?” asked the bearded man with a beatific smile, as if he’d just thought of this question himself when in fact he was quoting the alliterative title of the meteorologist’s academic paper.

I happened to know the analogy originally invoked the flap of a seagull ’ s wing. I’m proud to say I did not mention this.

“Well, could it?” asked someone finally, and the bearded man explained that theoretically it could, or it could prevent a tornado.

None of us had any experience with tornadoes, so there was a lull in the conversation.

“Shall we lounge about in the lounge room?” Hazel gave a sloppy wave of her arm. She had crossed that invisible line from charmingly tipsy to embarrassingly drunk.

Her husband said he would take care of the coffee, which was sensible, as we didn’t want Hazel in charge of hot water.

There was not enough seating for everyone, so I sat on the floor next to the coffee table. As a young woman I enjoyed sitting on the floor and often did. I no longer do, although, ironically, it is now recommended that I should. A Brazilian doctor has developed something called a “sit-to-standing longevity test” where you are meant to rise from the floor to your feet without using your hands or knees. I tried it last year with my friend Jill and do not recommend it. We both failed. Although it made us laugh.

“Cherry!” ordered Hazel. “Tell everyone what your mother did for a living!”

“Everyone has heard quite enough about my mother tonight,” I said firmly.

“Cherry’s mum was a famous fortune teller. Madame Mae! Ooooh!”

“Did you inherit her skills?” The attractive man offered me his upturned hand. “Can you read my palm?”

“No,” I said. I resisted the temptation to take his proffered hand. “I didn’t inherit her skills. My mother always said I had the intuition of a potato.”

“A potato!” said the attractive man. “Well, you certainly don’t look like a potato.”

His eyes did that quick flick—down, up—that men did. I’m not sure it’s allowed anymore.

I did look pretty that night and it was difficult to look pretty in the eighties. I wore a black pinstriped high-waisted skirt, a hot-pink shirt, and glittery triangle-shaped earrings. My hair was short at the sides and long and jagged on top. Hazel and I thought it looked marvelous. It’s not our fault. It was the fashion.

His wife tucked a long annoying curl behind her ear and said, “Is fortune-telling even legal ? Isn’t it, no offense to your mother…fraudulent?”

I understood and fully accepted that this was her way of getting back at me for the way her husband had just looked at me.

“Of course it’s legal,” said Hazel. “Cherry’s mum had a sign out the front of their house.”

She was correct. The small handpainted wooden sign that hung on two chains beneath our letterbox read: Madame Mae—Palms, Tea-Leaf, and Tarot. No Appointment Necessary.

In fact, appointments were necessary, but my mother never liked to turn away a customer. During the years in which she became wildly popular, in fact briefly “notorious,” there were sometimes as many as four people milling about our tiny sitting room. I had to offer refreshments, which was stressful.

“I believe fortune-telling is technically illegal,” said the bearded man apologetically, but unable to resist sharing his knowledge.

Before Google you could toss about all kinds of unverifiable statements at dinner parties, but in this case he was correct. Fortune-telling was technically illegal but rarely if ever prosecuted. My mother certainly never encountered any problems with the police, although she knew stories from her childhood of police going undercover to try to catch fortune tellers. You could only be prosecuted if police witnessed money exchanging hands. Before women joined the police force some fortune tellers refused to see male clients to avoid this possibility. There are still some parts of Australia, and many places around the world, where fortune-telling is illegal. I recently read about convicted psychics in America sitting for interviews before parole boards. “It’s all baloney, isn’t it?” jeered the “commissioners” (who seemed to be all men), forcing the psychics (who seemed to be all women) to admit that, yes, it was “all baloney.”

There has always been a special kind of fury and contempt reserved for women perceived to have supernatural powers. The last woman executed for witchcraft in the British Isles was stripped, smeared with tar, paraded through the town on a barrel, and burned alive.

To be clear: this was a legal execution.

The attractive man asked if I was descended from “a long line of fortune tellers”?

I said I was not, although in truth my grandmother also read palms. No sign on her letterbox, just whispered referrals, and my grandfather never knew about it. He wouldn’t have burned her alive, but he would have put a stop to it. Grandma kept the money she made in a biscuit tin. Every Saturday afternoon, she’d go to the bookie in Jersey Street, a few minutes’ walk away from her house in Hornsby, invest two shillings each way, and listen to the horse races on the wireless back at home while she grilled chops for tea.

“Always find a way to make your own money, Cherry,” she would say to me, shaking her biscuit tin.

I hear the faint jingle of my grandma’s coins whenever I do my online banking: the sound of precious independence.

I did not argue the legality or otherwise of fortune-telling with the woman with the annoying curl. Instead, I shifted the spotlight of attention away from myself by asking the bearded man if he had any thoughts on how new technology might change our lives in the future. He had multiple thoughts, as I’d known he would.

He was explaining why the “mobile phone” would obviously never enjoy widespread use when the doorbell rang.

I wish I could say I felt a shiver of premonition at that moment, but I did not.

Fullepub

Fullepub