2. Tybalt

CHAPTER TWO

TYBALT

G iant.

The bird man was a giant.

All my life, I had imagined Nemedans to be slight, sparse little people, so obsessed with their birds that they’d become like them, bedecked in feathers. They’d be like druids, hunched over with nests in their knotted hair and beards.

Except... no. The ones that Paris had brought back to Urial with him had been striking, their posture perfectly magnificent, their hair groomed, their eyes sharp. If anything, they’d looked like something slightly more than human, not more bestial.

And neither of them had stood as tall or as broad as the man who stood before my father’s throne now.

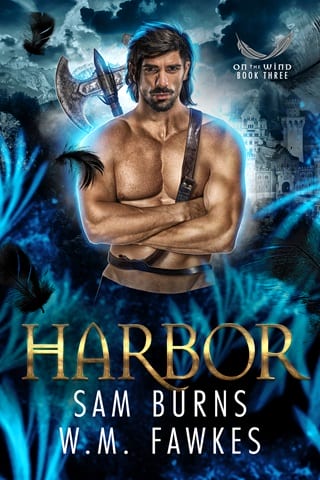

He had long, flowing, brown locks, and the white feathers threaded in his hair stood out more obviously than the feathers worn by either Chief Brett or Chief Killian, who’d come before. Nothing like this man had ever been seen in Urial.

And there was my father, high on his throne, acting as if the occasion meant nothing to him.

Perhaps it didn’t. He’d sent Paris away to treat with the Nemedans, but every single member of court had known that was an excuse to get him out of the way—or, more specifically, away from me. Still, the Nemedan was offering my father what he said he wanted, and it’d be a fool who rejected a potential prize, even one he hadn’t expected to ever get.

My father seemed to be battling with the thought of playing this game. The Nemedan hadn’t bowed, hadn’t scraped, hadn’t even complimented. He stood there, shoulders back, waiting, while my father’s nose flared in annoyance.

From my place below the throne and to the left of it, I couldn’t tell quite what either of them were thinking. These past months, my father had meant to shape me into an adequate prince and heir, but day by day, was giving up on the notion, and his mind remained as obscure to me as ever.

I was hopeless, and I’d never stood right at his side. No, that place was reserved for his trusted advisors—people like Lord Gregory and Paris’s father, Sampson. Stolid, reliable men.

Not youths with a taste for them.

“You may start with giving us your name, Nemedan,” my father said finally, leaning on the arm of his chair and trying to feign boredom.

But I saw the flash in his eyes, the seething fury when the Nemedan didn’t bend or buckle before him. It was the same look he’d often sent Paris, that the kind lad had remained oblivious to for so long—a look he reserved for people who had offended him so deeply that they could never hope to recover in his estimation.

“Orestes.”

Orestes , I mouthed, the shape of his name sweet on my lips.

Yes, I could work with that.

Father’s brows rose high. “Just Orestes?”

The Nemedan nodded. “Orestes, of Nemeda.”

I had to bite my lip against a laugh, and I ducked my head as the sharp glare of the king turned my way.

My father was looking for some reason to treat this man well, or perhaps a reason not to, beyond simply that he was foreign. He wanted to know what he could get away with, and Orestes gave him nothing.

His expression remained passive, detached. His arms crossed his broad chest.

I . . . had never seen this.

Not once in my twenty-five years had I been able to stand so fearlessly before my father, uncaring what he said or did or took from me.

And because he gave my father nothing, my father didn’t know how to handle him. He couldn’t dismiss him as a flighty, frivolous disappointment. If he rejected him, he stood to miss an opportunity, to offend our southern neighbors, to?—

I didn’t know. I didn’t know how this man could change Urial, but the air was suddenly charged, as if it were an inevitability that he would.

And my father shrank, his fingers gripping his throne like claws.

“Then you may make a proposal,” he hissed, “and harbor here until I have heard it.”

With a snap, he summoned an advisor to his side. The man bent to listen to my father’s instructions and as soon as he was finished, hopped off the dais to stand before Orestes of Nemeda. He had to tip his chin up far to meet the foreigner’s eye.

“If you would follow me, sir, we shall find you... appropriate accommodations.”

In the royal wing, hopefully. I, for one, wouldn’t mind having such a vigorous neighbor.

The advisor turned toward Orestes’s escort. “Emilien?”

The unfamiliar lord bowed his head. He was from the south, I knew, but only because he’d arrived in the company of the Nemedan. I’d rarely ever seen him at court, and that, coupled with his plain features and advanced age, made him rather inconsequential to me.

“I’ve written ahead and will be visiting with cousins during my stay,” the lord said with a placid smile.

Father’s advisor seemed pleased to have one less room to appoint.

Every single peer of the realm held their breath as Orestes was led away by the man.

Then, the room erupted into whispers, everyone rushing to their friends to speculate about what the Nemedans could possibly want, if they had seen his feathers . Already, we thought the Nemedans were barbaric, even dangerous. This one looked like he could kill any one of us with his bare hands. How did a man get so broad?

As people moved about, darting between clumps of gossipers to find the most delicious speculation, my friend Mercutio stepped to my side.

He was particularly sly. Clever, even. The shape of his smirk promised some cutting observation.

While starry-eyed Paris had batted his lashes in court, blushed at a word, and followed my every step, Mercutio was far too smart to show his hand in front of my father. That alone was the reason he remained at court and Paris had been all but banished to the wild south.

“I’d not thought the Nemedans would return to court after how horrendously their visit played out last time,” Mercutio said, staring at me.

I’d not told him the full story of it, how I’d assaulted our guest and been rebuffed most disgracefully. I didn’t mind the game of it—pressing for more and getting rebuffed was common for Urial men of my inclinations—but when that silver-haired one had cut me to the quick... No, that was a story I would take to my grave, and none of Mercutio’s sly probing would get me to share a word of it.

Dismissively, I waved a hand after the Nemedan. “A dozen tribes, all pledged to almighty birds. Who knows why they do as they do? Perhaps his clan finds the north more approachable than those who took Paris from us.”

“Did he strike you as particularly happy to be here?” Mercutio challenged. He looked his best when he was snarky and dissatisfied, and the arch of his chocolate-brown eyebrow was damnably perfect. Never in my life had I managed to look so invincible.

I hollowed my cheeks. “Well, no. But who is at this time of year? The snows are just around the corner.”

Frankly, in some ways, I couldn’t wait. When the world turned cold and quiet, everyone shrank into their own business, stayed by their own hearths, and waited for the worst of the season to pass. It was the perfect time for me to do as I liked, slip away, even. When the snows were only ankle-deep, I could take my horse, Biscuit, up into the mountains and disappear, sometimes for days. Father was less prone to notice I was gone when winter came.

Mercutio tipped his head curiously. “You like the look of him, don’t you?”

I scoffed. “Don’t pretend you don’t.” Mercutio and I had fallen into each other’s beds often enough that I knew his tastes ran as wild as mine—pretty, soft youths like Paris to bulky, formidable warriors like our new guest. “But as your prince, I demand first shot at him.”

Yes, he was wonderfully built and quite handsome, but even more importantly, my father’s skin would absolutely crawl when he found out his abysmal son had seduced his way into a Nemedan’s bed.

Ever so sweetly, Mercutio smiled and held out his hand in the direction Orestes had been led off. “Of course, my prince. Chase the barbarian at your leisure. I shall be waiting for him to discover better taste in company.”

He laughed as I shoved him and spun to leave. If I was lucky, I’d escape before my father remembered to call me to duty.

Fullepub

Fullepub