Chapter Two

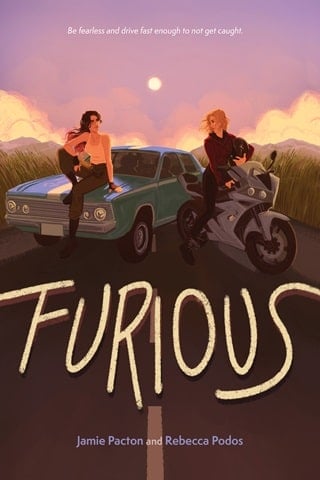

Once upon a time, the 2004 Yamaha YZF-R1 was superbike royalty. I've tattooed its stats on my brain the way a football fan memorizes their favorite player's … ball speed or whatever (I don't football). A 998cc, liquid-cooled, short-stroke, twenty-valve, in-line four-cylinder engine capable of producing 180 horsepower at an absolutely wild-for-the-times 12,500 rpm. A narrower motor, valve angle, fuel tank, and frame compared to the 2003, and massively strong. Fifty-six damn degrees of cornering clearance.

Not that I've ever actually tested the capabilities of this bike. At least, not alone.

Despite the dust motes that speckle the air, the liquid silver side panel in front of me is spotless. It'd better be. I polish the R1 every other week, even though it hasn't seen its owner for three months now, roll it backward and forward to rotate the tires, run the engine, and service the chain—the reason I'm on my knees in a storage shed in North Carolina summer weather, soaked to my elbows in kerosene and sticky with chain spray.

I've just finished wiping the extra lube from the links when my phone bleats repeatedly. That alarm means I've got an hour and fifteen to clean up, change, and clock in at Putt by the Pond. Mopping my forehead sweat with my equally sweaty bicep, I scoop up my supplies and step carefully around the other dirt bike in the shed to put them away. My hand-me-down Husqvarna leans forlornly against its kickstand; probably it feels abandoned. It's been in the dark for just as long as the R1, but I've got too much going on to get to Devil's Paradise, our local motocross track. Between my part-time job at the local mini golf, go-kart, and pinball parks, the two-evenings-a-week volunteer program I cofounded for the sake of my looming college applications—and for, like, the general spirit of humanity—plus the, you know, family stuff, the summer before my senior year has been … complicated.

I set my supplies on the makeshift workbench I cobbled together from a row of leftover paint cans with Max's old skateboard propped across the lids. Seems like everything in the shed is my sister's old something. There along the back wall: milk crates full of her paperbacks and comic books and old concert T-shirts. Bagged up in a corner: her riding gear. Carefully packed into a box behind the spare gas cans: her motocross trophies and medals, dozens and dozens of them. Everything she's outgrown.

Except the R1.

Stretching my back, I walk out of the shed into sunshine and cicada song. I blink in the light for a long moment, basking in the damp breeze and fresh air, before padlocking the door behind me. Then I walk across the grass, past Dad's vegetable beds, and toward the house, where the shower calls to me.

But when I slip through the screen door, I stop on the mud mat at the sight of Mom. She stands at the kitchen counter in her workout clothes with a pile of mail in hand, her shoulders stiff in that familiar way.

"Anything in there?" I ask, absolutely failing to sound chill.

With a bone-deep sigh—she already knows I know—Mom slides the postcard halfway across the counter to me. "Wash your hands before you touch anything," she warns.

I hold my hands out in front of me like surgeons do in medical dramas, careful not to brush against the furniture on the way to the sink (and fighting the deadly urge to throw my filthy arms around Mom in her cream yoga top). I even elbow the tap on. Toweling my hands on my pink shirt, I make myself walk slowly back to the postcard.

This one's glossy, bright blue, and says Greetings from Boston in bold bubble letters. Inside each letter is a picture of a building or a bit of skyline. As much as I want to, I can't flip it over with Mom right there, pretending not to watch me. So I wedge it into my back pocket and announce, "I'm gonna go shower."

"You don't need to run off, El," she says.

"I'm not, I just … I have work at three, and I don't want to be late."

"Oh. Well, good. I'm glad you're taking it seriously. I know it's only a summer job, but—"

"Mom, I really gotta get ready," I cut in, keeping (I think) all traces of annoyance out of my tone even though I've heard my parents' I know it's only a summer job, but speech a dozen times since vacation started.

She reaches out as I pass, but when she can't find a clean place to touch me, she drops her manicured hand to her side. "Want me to drive you to work? I'll pick you up after," Mom offers.

"Why, do you need the minivan?"

My mom's a science teacher at the middle school, which frees up her summers. Unfortunately, it also frees up her oatmeal-colored Toyota Sienna, which I share because we're down to two cars since Max, and Dell's Hollow has no public transportation unless you count the little bus that carts folks from the senior center to the grocery store once a week. Plus I think my parents like being able to ask where I'm going and exactly when I'll be back, while pretending it's all about the car. As if I'm ever going anyplace I shouldn't.

"No, I don't need it," says Mom, "but I was thinking—maybe we could grab some ice cream, bring it home for Dad?"

"I told Zaynah I'd give her a ride home, though." My best friend, Zaynah Syed, and I applied for our jobs together at our high school's teen employment fair this spring. It was either Putt by the Pond or the town's exciting new Applebee's, and I'm allergic to barbecue sauce.

Mom shifts into tree pose without meaning to, tapping her nails against the counter. "You can invite her over for ice cream, if you like. We hardly see your friends these days."

"Oh. Sure. Okay." I offer a little smile.

"It's a plan, then." She turns back to the mail, sliding a finger beneath the envelope flap of some bill. "And please use one of the beach towels to wash up. If you have to mess around in the shed, I've asked more than once that you not get the good towels dirty."

Well then! Mother-daughter moment over, I guess.

I take the stairs two at a time, and though I really do have to get ready, I pause a moment before skipping the second floor with my bedroom and bathroom to head up the spiral staircase to the attic. Which is really more like a loft; this became Max's space when she was too old to share a bedroom with her five-years-younger baby sister. She painted the squat walls and sloped wood a banana pudding yellow, so when I push through the shower curtain that hangs on a circular rail around the entrance, I always feel like a little chick inside a yolk. Even though most of her stuff's been shifted to the shed, the room still smells like her, I swear. Like her candles from the World Market in Fayetteville, and her clothes after riding—hot engine oil, smoldering brake pads, and exhaust—and like the jalape?o popcorn we'd eat while binge-watching our all-time favorite movies.

I'm talking, obviously, about the Fast Furious films.

It's been a year and a half since my sister dropped out of college and came home to Dell's Hollow. It was immediately clear how tense things were between Max and our parents, but if I'm honest, I was happy to have her back. Even after she'd moved upstairs, her curtain was never closed to me. Whenever she was having a shitty day or could tell that I was, we'd curl up together in her daybed with her laptop. We'd watch Dominic Toretto and his found family pull off increasingly improbable stunts and heists while Max lamented every custom 1969 Ford Mustang run over by a tank, and every 2008 BMW M5 thrown through a building. We're not Car Girls?, but we share an encyclopedic knowledge of the FF movies and their many trashed classics.

Then there was Letty Ortiz.

The moment Michelle Rodriguez first stomped on-screen in her flame-painted motorcycle boots, camo pants, and resting go-fuck-yourself face, a little lesbian lightbulb clicked on over my head. Or possibly bi lightbulb, or pan—I haven't nailed it down just yet. When Letty slid that black Honda Civic under the cargo truck during the electronics heist, I swear eleven-year-old me had a religious experience like I've never had during Shabbat services at Temple Beth El. Naturally, Max was the first person I came out to (as though she hadn't noticed that whenever I looked at Letty, the tips of my ears turned as deeply red as the Nissan 240SX Letty drove in Race Wars). My sister tucked my hair behind my burning ears, smacked a sloppy kiss on each of my cheeks, and announced, "Okay El, we're putting this marathon on pause to watch another classic: Blue Crush. It's gonna change your life."

Flopping back onto the daybed, now permanently in day mode, I finally turn over the postcard. I skim my thumb across Max's chaotic handwriting on the address lines:

Eliana Blum

15 Cider Lane

Dell's Hollow, NC 27010

As always, the message is nearly as short as the address, just a couple of scrawled sentences:

Miss you El. I heard that song in a diner last week, the one with the snake for a necktie, and thought about you. Hey, do me a favor and tell Jolene I want my jacket back? I think I left it in the shop.

No return address. There never is, though the postmark is from Boston, sent June 1—two days ago.

I sit upright as the realization hits me.

Bursting back through the shower curtain, I practically rappel down the spiral staircase and run for my own bedroom. From the color-ordered row of mini notebooks in my desk cubby, I pull out the red one with my postcard collection tucked inside. It's not much of a collection, just five other cards sent over the last three months, postmarked from five different cities:

Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, March 6.

Tupelo, Mississippi, March 17.

Muskogee, Oklahoma, April 2.

Great Bend, Kansas, April 10.

Boston, Massachusetts, May 1.

The cards came so quickly at first, I figured they were sent from the road, slipped into a mailbox as Max passed through town. But twice is a pattern, right? That's what my parents say, as in: Once is a mistake. Twice is a pattern. According to the cards, Max has been stationary for over a month now.

Huh. I would've thought she'd land someplace in the south, or anyway, a city with a racing scene.

As the box full of trophies in the shed attest, my sister is fucking extraordinary on a track. From the moment my parents bought a used kid's mountain bike for fifty bucks and strapped a helmet on her so she could ride easy park trails with them on weekends, Max was absolutely fearless. She moved up to a little 70cc mini dirt bike when I was still a toddler, and she qualified to compete at Loretta Lynn's—that's the AMA Amateur National Motocross Championship in Tennessee—a month after her bat mitzvah. Then again when she was fifteen, and sixteen, and seventeen. That last year, she took third place in her category. Some of my earliest memories are of watching Max on her (now my) white-and-yellow Husqvarna, slicing through plumes of mud and gravel I could practically taste from the stands, soaring over the jumps and trusting the track to catch her.

It was Max who got me on the track, riding the 70cc we still had in the shed back then. And look, I wasn't bad! I did some junior events at Devil's Paradise in Deerfield, and even won medals of my own. They're still tacked to the corkboard above my desk, alongside my Honor Society medallion, merit medals, and a community award for Zaynah's and my volunteer program.

Still, I could never ride like Max. I wasn't fearless enough to keep it pinned.

Max just had it. Her coach said she did, and so did the scouts who watched her race at Loretta Lynn's. Everyone was pretty serious about her career; her coach even suggested homeschooling so that she could compete more often and rack up enough points to apply for her professional license even sooner. She'd been racing with the pros as an A-class amateur for a while and wanted to compete full-time as soon as she graduated high school. Everybody wanted it for her.

Except my parents.

They expected her to go to college. Max fought it—I know because I heard their barely muffled shouting matches drift up through the floor while I did my sixth-grade science homework in my room—but she went in the end. Which is I guess where the trouble started between them. And when she dropped out just before her last semester, it got a lot worse. Max never told me why she left college so close to graduating, except to say, "I just wanted to go off-road, El, you know?"

I didn't know. Even then, I was already planning for college, asking my guidance counselor questions about sports medicine and programs near-ish home. But like I said, I didn't care, because I had my sister back.

My sister's favorite place in the world might be behind the handlebars, but mine is on the passenger seat. Just me and Max on the R1, the sky above us blue and smooth as sea glass, my hands fisted in her jacket—

I read the nothing-message one more time:

Miss you El. I heard that song in a diner last week, the one with the snake for a necktie, and thought about you. Hey, do me a favor and tell Jolene I want my jacket back? I left it in the shop.

She means Jolene Boyd, Max's boss for the year she lived at home. Kind of a town icon, Jolene clips around the garage she runs in heels as red as her dyed hair. Jolene only works on cars, but she's the one who tipped off Max that a 2004 Yamaha YZF-R1 was sitting in a friend-of-a-friend's shop for a sliver of what it was probably worth. She even loaned my sister the money to buy it (our parents certainly weren't gonna) and let me hang around while Max used the shop tools to fix up the bike in her off-hours. As she worked, Max would recite the superbike's stats to me like a bedtime story, over and over again, and I'd ask her to tell me them just one more time.

The R1 is my sister's greatest treasure. She asked me to take care of it for her while she's gone, but she'd never have left it behind if she planned to stay away for months. I guess we both thought Mom and Dad would let her come home by now.

Funny Jolene never called to tell us she had Max's riding jacket, though. And I don't know how Max plans to get it back from her without a return address, unless … Unless Jolene knows something I don't.

I check my phone again to find I'm down to an hour before work. If I want to wash up, I have to get back on track. It says in the employee handbook (which Zaynah and I studied together before starting) that Putt by the Pond's policy is a verbal warning the first time you're late to a shift, and a write-up for the second. Even if I haven't been late yet, I could be late again for totally unavoidable circumstances. Then I'd be kicking myself for the warning I could've prevented. And Mom's right—it might only be a summer job, but I'm counting on them to hire me back next summer, so I can save up for my own car before college. UNC–Chapel Hill is over a four-hour drive from Dell's Hollow, and if I get in there, I can't have Mom and Dad dropping me off and picking me up from campus in the Oatmobile. I simply cannot.

And I really should wash up, because I must smell like the love child of a gas station and a compost heap.

I stand frozen with indecision in the middle of my bedroom for a long, precious moment before springing to action, peeling off my oil-stained joggers and pulling on a clean pair of jeans. My T-shirt is grease spotted, but I'll be changing into my work shirt anyway. After slapping on an extra layer of deodorant and finger-scrubbing a streak of grime from my short blond hair (with some beachy-smelling dry shampoo on top to try and mask my odeur), I grab my backpack and run out my bedroom door.

I do a lap of the first floor to find Mom, now in her chair in the living room, immersed in her latest paperback biography. This one looks like it's about a figure skater from the ‘80s, judging by the cover.

Already shrugging on my backpack, I say, "Hey Mom? Zaynah just texted, and her dad can't drive her to work anymore, so I told her I'd pick her up." The lie burns in my cheeks, and I hope she'll think I'm still overheated from working in the shed. It's not that I think one little white lie is so terrible, but I know what it would mean to my parents if they found out.

Mom starts to set her book down. "All right, just give me a few minutes, and I can—"

"That's, um, that's okay, ‘cause we might get coffee on the way, so … maybe I can just take the minivan for the afternoon, and we can do family ice cream tomorrow? Or actually, I have a volunteer shift at the Syed's. Um, so Wednesday?"

"Oh." The way her forehead crinkles sends a fresh wave of guilt all the way down to my toes. But what am I supposed to say? I know you hate talking about your other daughter, the one you guys kicked out of your lives and mine, while you were at it, but I have this hunch….

"That's fine, El."

"Okay, cool. But Wednesday, right? We can do ice cream Wednesday?"

"Sure. We'll see how the week goes." Mom returns to her paperback.

By the time I've grabbed the keys from their hook and escaped into the van, I'm sweating worse than I was in the shed. Still, I force myself to start the engine and pull away without glancing back at the house. Who has time for second thoughts? If the two traffic lights between Cider Lane and downtown Dell's Hollow are good to me, I can easily make it to work by three—after stopping to talk to Jolene.

See, my sister's boss wasn't just her boss, but like, her mentor. Her Yoda in a bright green mechanic's jumpsuit and spangly chandelier earrings. So if anybody who isn't my parents knows where Max is—knows how and where to send her the prized possession she left behind—it has to be Jolene Boyd.

Fullepub

Fullepub