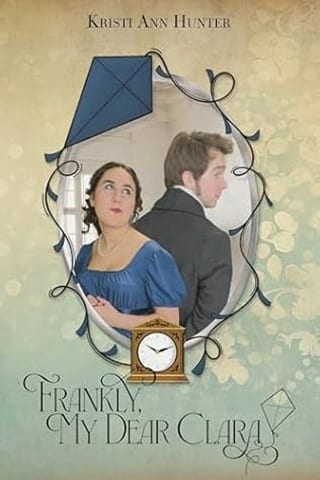

12. Chapter Twelve

H ugh curled his hand around the delicate spring he’d just removed from the chronometer on the table. The sharp edge bit into his palm, but that wasn’t enough to pull his attention from the doorway.

Daylight was just visible through the window behind him, but it would be several hours before the sun trailed through the window enough to properly light his worktable. The lantern he’d placed on the corner sent out a circle of light that seemed to accentuate his unexpected visitor.

Miss Woodbury stood just inside the room, dressed in a pink morning gown, hands wrapped around a sturdy white mug the servants had probably shuddered to provide for her. Steam curled from the mug and caught the steady flicker of light. He followed it up until he met her wide eyes.

The surprised O her mouth had dropped into almost made him laugh, but he kept his wits about him as he set the spring and his tool aside and rose to his feet. He gave her a sharp bow of his head. “Good morning, Miss Woodbury.”

“What are you doing here?”

His gaze dropped to the table strewn with parts and tools. “Working?”

“Do you not have a shop for that?” One hand smoothed down the edges of her wrap. “And reasonable hours?”

“Seeing as the shop isn’t mine, and this work isn’t for the shop, no, I don’t have another place to do this.” He shrugged. “And I also have to do it on my own time.”

The obvious discombobulation of his companion made him want to continue to play out the conversation, but he had a limited amount of time to work before reporting for his paying job. That made it necessary to volunteer the information she sought and get back to work.

“Your cousin offered this room as a workspace since it gets a great deal of evening light. He and his friend are sponsoring my entry for consideration in Greenwich.”

She blinked a few times. “It isn’t evening.”

“That’s why I have a lamp.” He couldn’t stop the grin that pulled at his lips. “But I plan to return this evening. I’m afraid I woke this morning with an idea I didn’t want to lose, so I came by to test it and add it to my notes.”

Not to mention a portion of his evening visit was likely to be taken up by a game of billiards and dinner. It was a strange situation, but his friendship seemed to be part of the exchange for funding, and Hugh had found he was more than amiable to the cost.

Miss Woodbury looked from him to the table and back again before slowly taking a deep drink from her mug.

He expected her to utter a quiet goodbye and beat a hasty retreat, and he found the idea unsettling. Despite the amount of work he needed to do in a very short amount of time, he wanted her to stay.

Company wasn’t a normal part of his work environment, but he’d found that talking to her made his mind consider alternative ideas. And he simply liked doing it.

So he tried to keep her there, even as he picked up a pair of delicate tweezers. “Was your evening enjoyable?”

“I suppose.” She frowned as she drank from her mug and wandered over to the window. “It was productive, which is likely the best I can hope for.”

“Why wouldn’t you hope for enjoyment?”

She tossed him a dry look over her shoulder. “I am in London.”

“Most of the world considers London a center of culture and entertainment.”

“Which is precisely the problem.” She shook her head. “While I am certain God places those who are stout of heart in the middle of the mire to cleanse those embedded in it, I find my inclinations are to be more removed from such worldly considerations.”

Hugh coughed and gave his head a brisk shake to loosen the scrambled thoughts her overserious words inspired. “Worldly considerations?”

“As a businessman, I wouldn’t expect you to understand, but there is little good and honorable and pure in London for me to focus on.”

Hugh used the tweezers to affix the spring to a thin hook, then set the tweezers aside to give Miss Woodbury his full attention. At the moment, she was far more fascinating than his new chronometer. “Why would you confine God in such a way?”

Her frown turned from the window to him. “I am not confining God, and it is a horrible idea for you to suggest. God is all-powerful and capable.”

“Is He?” Hugh made himself look thoughtful. “Even capable of putting something good, honorable, and pure in the coal darkened streets of London?”

She sighed and narrowed her eyes at him. “I see what you are doing.”

That’s because she was an intelligent woman. “I should hope so.” Hugh grinned. “Otherwise, I would have to seriously question my abilities at communication.”

Her attention dropped to the gears and springs strewn across the worktable. “Why do you make clocks?”

“I make clocks because Mr. Johns pays me to.” He looked across the table and a deep sense of purpose settled into his middle. “I make chronometers because the world is large and the only thing every place and person on this earth has in common is that they move forward through time to the next moment.”

“There is a difference between chronometers and clocks then?”

He nodded trying to restrain his words to something simple that wouldn’t have her fainting in boredom. “You carry a pocket watch, do you not?”

“Yes.” She frowned. “It is not on me now, of course, but I have taken to carrying one here in London.”

“You didn’t carry one before?”

“No.” She lowered herself thoughtfully onto the edge of a settee that had been pushed against the far wall. “Which is, I think, evidence of the goodness of the countryside.”

“You find knowing the time of day a source of evil?”

“I find the limitations placed on me by such adherence to time a distraction from allowing God to mark my path.”

He’d never heard anything so strange in his life. Yes, at this moment, she consumed every corner of his mind, burying all thoughts of springs and counterweights. Her views of time were even more important than his desire to educate people on how much more reliable chronometers had to be than a regular clock.

He stepped back from his worktable but didn’t cross the room to sit next to her. It wouldn’t do for this interlude to appear cozy, should someone else find them here. Best for him to stay standing and the table to stay between them. She might feel comfortably free in this house, but he was well aware that his ability to continue to work and design here relied on the goodwill of her cousin.

The viscount was quite affable for an aristocrat, but he wouldn’t take kindly to Hugh doing anything that would call Miss Woodbury’s honor into question.

In fact, Hugh should make his excuses and leave the woman to her own space in her own home, but he was too fascinated to do so.

In Hugh’s eyes, time was a captivating gift, a way to connect people. It didn’t matter how wealthy someone was or how disreputable. Five o’clock was five o’clock for everyone.

“You find knowing dinner will be served at half past five to be limiting God’s direction?”

Her nose scrunched up. “It sounds ridiculous when you put it like that, but if you’d ever spent time in the house of a vicar you would know that, yes, it is in a way. I don’t know the number of times Cook had to keep food warm or make up a cold plate because Father’s duties required his presence in the evening.”

Uncle Patrick’s house was much the same way, so while Hugh could recognize the truth in her words, he knew such cases were the exception rather than the rule.

“Is it also limiting for a church service to start at a particular time?”

She pointed a finger at him, and the side of her lip twitched. “You are deliberately twisting my meaning, sir, in an attempt to knock me sideways, but I shall not be slain in such a manner. I am aware that time must be observed when multiple people, particularly members of a community, are attempting to align their days or weeks at a certain point.”

“Then what makes it a problem in the city? That is all people are doing here.”

“There’s simply so much of it.” She set her mug on the floor and stood to pace from the settee to the door and back again. Three steps, turn, three steps, turn. It was an incredibly short walk that almost made her appear to be doing some strange sort of dance.

He fought the wide grin the picture inspired.

Suddenly she stopped and faced him, hands on her hips. “It is one thing for someone to know that dinner is taking place at half of six or that the Sunday service commences at ten in the morning. It is quite another to have one’s entire day blocked off in predetermined divisions. To do so is to tell God how you will spend your day instead of allowing Him to direct it.”

“You make no plans for tomorrow?”

“Ye know not what shall be on the morrow.”

“But you are here in London, attempting to make a marriage match. What is that if not planning for the future?”

She sighed. “That would not be my first choice.”

Hugh chuckled. “And yet.”

“My need for a husband, and the provision such a relationship brings, is simply an indication of the fallen world we live in.”

“So is that dress you are wearing.”

Heat crawled up his neck at the implication of his statement and a matching flush appeared on her cheeks. For a moment they both stared at each other. He didn’t know what she was thinking, but he was giving serious consideration to what it would be like to hold her in a dance or walk along the street with her arm tucked in his.

They were all but alone in this quiet house, and he was suddenly very aware of that fact.

He cleared his throat and busied himself setting the table to rights. “What I mean is there are many aspects of this world that exist because of man’s imperfections. Knowledge of time is simply one of those. Why do you consider it worse than the others?”

She retrieved her mug but remained standing by the door. “Have you seen Ambrose’s diary?”

“Er, I confess I have not.”

“It is full of meetings. Some of them are with himself so he can go over ledger books or answer correspondence. Even his leisure time is predetermined.”

That seemed a normal way of living to Hugh. Many of his customers lived life in such a way, which was why their clocks and watches were so important. “What is wrong with that? It seems normal to me.”

“I suppose it is normal if one lives life consumed with business or politics.”

“I’m to gather from the tone of your voice that you think little of such endeavors.”

“They do seem to swallow the whole of London.”

“It is a city. One can hardly grow a crop of wheat along Pall Mall or keep chickens in Grosvenor Square. There are still sheep in Hyde Park, but they are the concern of a select few.”

“That is my point, exactly.” She indicated his worktable again. “The more people concern themselves with things they make instead of caring for and developing that which God placed under our domain, the further we get from his holiness.” She ran a finger over the edge of a gilded frame on the wall. “And then we become consumed with gaining more of it.”

An immediate rebuttal formed in his mind, but he clamped his lips shut to keep it to himself. The intensity of her words belied a significant conviction, and that deserved his honest contemplation.

After several moments of consideration, he concluded she was wrong. Mostly.

“You’ve a kitchen garden at the rectory, I presume?”

She frowned in confusion. “Of course.”

“Do you use a rock to prepare the soil?”

Her frown deepened. “Of course not.” Her chin lifted a notch and her gaze slid away from his. “It is normally prepared and planted by someone else, but I’ve worked our garden enough to know what a hoe and a rake are.”

“And how long have such tools been used in gardens?”

Wide eyes turned back to him. “How would I know?”

He shrugged. “I haven’t the faintest as I don’t know the answer either. What I do know is that Cain didn’t have them.”

“Are you referring to Cain in the Bible?”

“The very one.”

“Of course he didn’t have one. He’s”—she waved her arms about—“one of the first people to walk the earth.”

“Yet someone, somewhere invented such tools. Someone invented the needle you use to make stitches and the stove your cook uses to make toast. Do you consider visiting the ladies or your parish a noble, God-honoring pursuit?”

“While I believe you are trying to trick me with this question, the answer is obviously yes. It is important to know what is going on in the parish and for the people to know they are cared about.”

“The pot that holds your tea and the carriage that takes you to the village are all things that changed how people spent their day and where they gave their attention. And yet, you have no problem seeing how God can use these items.”

“What is your point?”

“My point is that maybe it isn’t a lack of good and honorable things in the city, but a determination not to see them for yourself.”

She stood and narrowed her gaze. “That is quite the stretch, Mr. Lockhart. One has only to consider the many areas of Town where I am not allowed to venture, or how very delicate my reputation seems to be while I am here, to know there is far more darkness lurking here than in the country.”

“Is it more darkness or simply different risks?” He’d been to the country to deliver large clocks, and he’d heard the customers discuss their days away from the city. He had yet to see evidence that people who collected their own eggs instead of purchasing them from the market were all that more holy.

“Speaking of risks, the hour grows late, and I should not be dallying alone in this room with you.”

He couldn’t refute that statement. The gentlemanly thing to do would be to leave her alone in the room and make his way home, but he wasn’t particularly keen to leave her with his work when she seemed to despise it.

Lord Eversly has assured him the staff would be instructed to leave this room untouched and the thin collection of dust on the edge of the table indicated he had followed through.

Miss Woodbury’s presence this morning meant she had not been given the same instruction. She might not give his work the same respect.

Yet, he considered himself a gentleman and the right thing to do was still the right thing to do. This was more her home than his. “I will—”

“I bid you good day.” She clasped her mug to her chest, stuck her nose in the air, and strode from the room.

Hugh stood for several minutes, feeling oddly like he’d been put in his place instead of having the last word in their near argument.

Finally, he picked up another spring and turned it in the light of the lantern.

When he’d taken his apprenticeship, Uncle Patrick had made Hugh memorize Colossians 3:23 and recite it every morning. He still rolled the verse around in his mind when he woke each day.

And whatsoever ye do, do it heartily, as to the Lord, and not unto men.

Never before had he stopped to ask himself if the burning desire to make a better chronometer was a fitting interpretation of the verse. His entire life felt far more unstable than it had half an hour ago.

And he had Miss Woodbury to blame.

Fullepub

Fullepub