4. Avery

“Brush your index finger against the D string like this.” Avery angled the neck of her guitar, showing the class the placement of her fingers. “Otherwise, you’ll muddy the scale with ringing from the rest of your strings.”

“I thought you said we had to maintain finger posture,” a young man with coal-black eyes whined.

“I did, Tom, yes.” She acknowledged his question with a nod. “But once you’ve mastered finger posture, you can let it slip, as long as it’s intentional.” Putting her money where her mouth was, Avery straightened her seat on the tree stump and played a rapid pentatonic scale, demonstrating first with the muting technique, then a second time without. Tom’s eyes widened, intent on Avery’s fingers as she repeated the scale, again with the technique. After a third pass, she gestured for him and the rest of the class to try.

Notes thrummed out, some in perfect pitch, others a little flat. “You need to build strength in your pinkies,” Avery advised. “Reverse the scale and pay attention to your fretting.”

A series of discordant notes followed. Avery paced the circle, stopping by each student to correct their finger posture and placement and, in the case of the stubby-fingered howler, correct his grip altogether.

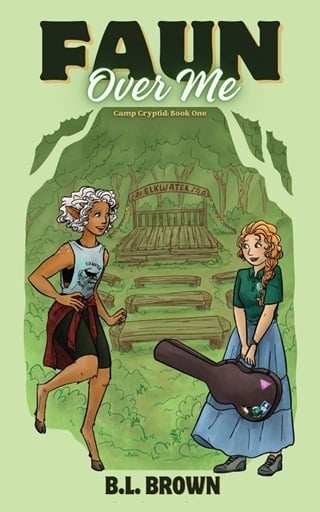

Guitar lessons were a new offering at Elkwater Music Camp, an idea floated by Director Murray after Avery missed the deadline to accept. The next day, Director Murray called her house and offered the idea of a guitar track to be taught by the Assistant Director.

It felt like bribery, especially when her father scoffed and told her they were “sweetening the pot,” but Avery hadn’t even waited a day to accept and begin drafting a lesson plan. Being wanted so badly for something had been too tempting to pass up. So she had accepted and, upon arriving in Elkwater, sought out the perfect place for her guitar lessons: a circle of stumps and sanded logs in an idyllic glade down a fairy-tale path leading away from the camp.

The students were clumsy, many of them learning the pentatonic scale on guitar for the first time, but they were bright and quick to grasp the concepts of composition and the theory behind the instrument. She kept her focus there: on the commonality of passion for music and the desire to create glorious sound together. They were a chorus of people weaving a song regardless of creed, color, or species.

“Ugh.” Tom played a sour chord and all but throttled the neck of his guitar. “This is dumb.”

“It’s not dumb.” Avery moved beside him. The boy was the youngest in her class by a few years but had become her most eager student in the last two weeks. “It’s a new technique, is all, and you’ve been playing guitar for how long?” He mumbled something, his head hung low, and Avery nudged him with her elbow. “What was that?”

“I said two weeks.” He raised his head, black eyes glinting with a sheen of frustrated tears. “But it’s not fair. How are any of us supposed to get anywhere when people like her exist?” He pointed across the small circle to a young woman with long, silken black hair parted down the middle. A series of tattoos, deep black against stone-gray skin, bisected her face from forehead to chin, and she played with her eyes closed, swaying in time as she played the scale to perfection in both forward and reverse. Avery’s lips parted in surprise, and she scrambled for a way to bring Tom’s focus back in line with the lesson when he continued. “What’s even the point? I’ll never be as good as a Spearfinger.”

At his accusation, the young woman opened her eyes and grinned fiercely at Tom, agile fingers continuing their dance over the strings, save for the wickedly sharp blade where her right index finger would be. It took Avery a second to recognize what the young woman, Kola, was doing—she was using her spearfinger to mute the strings, altering the placement to achieve a pitch-perfect pentatonic scale without the previously played strings ringing out.

The other students took note, their excitement and determination fading as Kola continued to play. Where before they had been smiling and focused, now they grumbled and set their guitars down—the magic broken by an inhuman.

“Kola, cut it out,” Avery barked. The scales faded away, along with the young woman’s triumphant smile.

“I’m sorry,” Kola said, glancing around the glade. Pink crawled into her cheeks, and she dropped her gaze. “I was just playing with the placement and I realized—”

“That wasn’t the exercise. If you’re going to learn to play guitar, you’re going to learn to play it correctly before you start to improvise.”

“Correct for who?” Another camper, a naga, asked. They raised their head, stretching their fingers wide. “Because I can tell you right now, my fingers are too long for half the placement you want us to practice.”

“Mine too,” Jared, a swamp ape, added. “And the guitar neck is so thin, I feel like I could crush it if I’m not paying attention.”

“Must be nice,” Eddie, the Howler, whined. “My fingers are too short for a power chord.”

“So we’ll get you a ukulele,” Avery snapped before she could think better of it. A quiet fell over the glade, the eyes of every student trained on her. “I mean, no. Not a ukulele, but we can—” Eddie set his guitar down and nudged it away with a claw-tipped, furred foot. “I didn’t mean—” She’d lost them. One look was enough to see that. Even the human students were eyeing her with distrust and leaning closer to their camp mates. “I-I can see we’re frustrated; why don’t we call it for the day? You all can practice on your own time, and we’ll pick the lesson back up in two days. Alright?”

The campers muttered their agreement, gathering instruments and leaving the glade in pairs. Eddie took off down the short trail to the camp before Avery could grab him to apologize, and she stood alone, fists clenched and shoulders hitched. Pinching her eyes closed, she willed herself not to cry, knowing she was utterly and irrevocably in the wrong.

He hadn’t deserved her anger; none of them had, but what was she supposed to do when they raised such solid points? How were any of them to compete when inhumans clearly had the advantage? It wasn’t fair.

“No,” she forced through her teeth. “No. That’s dad, not you.” And wow, was it her dad. She’d heard him go off on tirade after tirade against inhumans at the dinner table, in the club, and on the golf course. She had overheard him speaking with his colleagues over cocktails in their front room while Avery helped her brothers and sisters with their homework in the kitchen. She had heard, and she had answered her siblings’ questions, emphasizing that they ought to love thy neighbor as they love themselves, to love their enemies. To be gracious and kind. Teaching them all the ways they could be anyone but Nathan Payne. “That’s not Avery Payne.”

“They didn’t deserve that.” A warm, raspy voice broke through Avery’s thoughts, flying her eyes wide open. Beyond the circle of stumps and tree trunks, on the trail leading away from camp, stood an inhuman.

Their posture was odd, hunched to the side, but it did nothing to draw attention away from their figure. Willowy and lean, they wore an Elkwater Band Camp t-shirt that had been modified into a muscle tank, leggings cut off at the knees, and a flannel tied around their very narrow waist. Wild blonde curls framed their face, drawing attention to the high cheekbones and delicate chin dusted in sandy tan fur, and bright, wide-set coppery eyes were trained on Avery.

She swallowed, embarrassed at having been caught in her poor behavior. Heat flooded her cheeks, and when the figure hobbled forward, revealing a bandage-wrapped ankle and crutch, that heat rose to an outright burn as she realized who they were.

The mud-caked inhuman from the woods.

“Are you spying on me?” she blurted, too horrified to mind her words.

“No.”

“Good.” She spun away, hands shaking as she gathered her guitar and fumbled with the latch on her case. “I don’t need your judgment.”

“From what I just saw, I’d say you do.”

Avery sent a glare over her shoulder. “So you were spying on me.”

“Just seemed like for someone who doesn’t want any judgment, you were awfully quick to do so.”

“No, I—” She slammed the case closed and jumped to her feet, wanting—no, needing—to explain what had happened, that she didn’t mean to snap at Kola or imply Eddie couldn’t play the guitar. That she was trying even if she was failing, but it had to count for something. “I didn’t mean—”

“Nevermind.” The inhuman sighed and shook their—her. Director Murray had said she was a her—head. “I’ll just continue my hobble through the woods, where you decided to set up your lesson where anybody could come limping by.” She gestured at the trail with her crutch and hopped around, heading back the way she had come.

Avery watched her go, eyes drawn to the flex of muscle in her arm as she gripped the crutch, dropping to her long, lean legs and the bandage-wrapped ankle. Muted music from the field wove through the trees, brassy blurts and the call of a bugle, the driving tempo of snare drums, and still Avery didn’t look away. She chewed her lower lip, guitar case in one hand, as she replayed their brief conversation.

It was like being a living broken record, repeating the same groove in the vinyl over and over again. Unable to break free of the cycle until something, or someone, jostled the turntable, giving the nudge necessary to move forward.

And maybe …

A cymbal crashed and Avery took off at a jog, legs catching in her skirt. “Hey, wait up!” The inhuman kept hobbling along, neither faltering nor glancing back. Avery fumed and matched her slow-going pace, switching the guitar case to the other hand and reaching for her elbow. “Let me help you.”

“Don’t touch me.” She jerked her arm away, swaying off balance.

“You’re hurt,” Avery pointed out.

“I don’t need your pity,” the inhuman retorted.

“It’s not pity; I just want to help you.” She reached again, determined to help, to show she was good and kind—not a bigoted specist but someone who was trying to do the work to be better.

The inhuman leaned away, setting her injured hoof on the ground. She bleated in pain, waving an arm as she teetered backward. Avery acted without thinking, dropping her guitar case and snagging the only part of the inhuman she could reach. Her fist closed around the knotted sleeves of the flannel at her waist, and she tugged with all her strength. A bony, lean body far heavier than it looked collided with her, knocking Avery off-balance, and they went down in a heap. Her back hit the ground, and the air was forced from her lungs with a pained “oof.”

Spots danced in her eyes as the backlit treetops slowly came back into focus, and she gasped, struggling to fill her lungs. A heavy weight shifted, metal clanged against a tree stump, and a curly head rose, wide-set copper eyes glaring at Avery.

This close, she could make out the amber and gold shards in her pupils and each individual little bump on the dark tip of her nose. Avery had read somewhere that each dog’s nose was particular to the dog, the pattern as unique as a fingerprint, and her oxygen-deprived brain wondered if it were the same for whatever this inhuman was.

And then she acknowledged it was a very cute nose. Or was it a snout? Was it even polite to ask?

A thin upper lip curled back, splitting slightly in the middle and revealing blunt, white teeth. Avery’s eyes dropped to the inhuman’s plump lower lip as she snarled, “What in the hells was that about?”

“I was … trying to …” Avery wheezed, flicking her gaze away from the inhuman’s mouth only to be caught by that angry glare. Reality rushed in, and suddenly, she was all too aware of how their legs tangled together. Hyper-aware of soft downy fur and an ACE bandage rubbing against her shins. Of the scent of meadowgrass and peach, and the comfortable weight of the inhuman who had fallen on top of her. Her body heated from the roots of her hair to the tips of her toes. “I just wanted too ...”

“Help me, I got it.” She grunted and wriggled onto her knees, groping for the crutch and using it to hoist herself from the ground. “Please, don’t.”

“But I—” She scrambled to her feet, unsure how to finish that sentence. The inhuman had said no, and she wasn’t helping anything or anyone by pressing the point.

She cocked her head, gaze flicking over Avery before stabbing her crutch into the ground and swinging around. “If that’s what passes for your help, trust me, I don’t want it.” And with that, she hobbled away, still somehow graceful in the swing of her free arm and sure step of her uninjured leg.

As if sensing Avery’s lingering stare, she hesitated at the intersection of two trails and angled at the waist to meet Avery’s gaze. It was a beat. A moment. A rest in the score, stretching on, awaiting the conductor’s signal for the song to continue. Avery’s cheeks burned, her lips parted and dry, and with the crash of a cymbal from the field, she glanced down. When she’d recovered herself, she flicked her gaze up and found the trail ahead empty and quiet, as if the inhuman had never been there at all.

Fullepub

Fullepub