21. Cricket

“We need to go.” The woven reed door crashed against the wattle-and-daub wall. Three sets of eyes landed on Cricket, all ears intent on her. Ramble’s father, Iver, was the first to recover, lurching to his feet. Though shorter than Bosk, his antlers were no less impressive, the tips falling a hair’s breadth short of scraping the ceiling.

“Cricket, where have you been?”

“No time.” She slashed a hand through the air and held it out toward Ramble. “I need the keys.”

“The keys?” Her cousin blinked and shook their head. Iver cast them a wary look while their mother, Coni, frowned. “For what?”

“The truck. Charlie won’t drive me all the way to Elkwater.” She swept her hand in the air, gesturing for Ramble to hurry up. “We’ve got to go. The Georgia Men are there and they—”

“Oh, Gods.” Iver rolled his eyes and dropped to the ground, settling heavily on his knees. Pine straw and dust whoofed up in a cloud around him. “Coni, go tell Bosk his crazy daughter is at it again.”

“Dad!” Ramble glared at their father and stood.

“What?” he asked, taking a fork and attacking the sprouts and grains on his trencher. “Fool of a faun has been spouting nonsense about these Georgia Men for years.”

“Because it’s true!” she hollered. “And I have proof, which I can show you, but first, we have to get to Elkwater. Avery, she’s—”

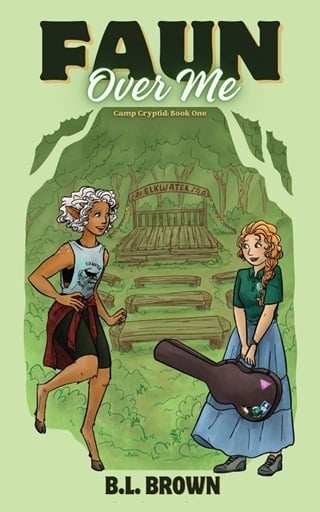

“Hosting a fundraising dinner at the camp,” Ramble finished. “She is fine; I spoke with Mac earlier.” They crossed the room, catching Cricket by the arm and guiding her out into a pale purple twilight. “Cricket, what is this about?”

“I went to Marlinton.”

“Oh, Gods.” Ramble smacked their forehead. “Is that where you’ve been? Bosk has been losing his antlers over you all day.”

“I saw the papers, the signatures.” She paced in a tight circle, trying to get out everything she had learned—about the properties, the Georgia Man, and the dinner. The pressure was building within her, the need to go, go now, fast. “And it’s hers, but it’s not. And that man was there, Ramble. He was there, he saw me, and—”

“Cricket.”

“I need the keys; we have to go.” She grabbed her cousin’s arm, all but pulling them in the direction of the trailhead where they had parked the truck.

Ramble planted their hooves. “No.”

“What?”

“I said no.” They jerked their arm out of her grasp and pointed at Cricket. “You need to go home. Get some sleep and get your head on straight.”

“We have to go. The camp is in trouble.”

“I know,” Ramble said, raising their voice to match. “Why do you think I am here? Mac is trying to raise enough money to expand and bring in more teachers and students. We are barely keeping the camp open as it is. She needs investors, but the people with access to that sort of money have a hard enough time accepting Mac, much less that she is married to me.”

“No, no, it’s not that,” Cricket shook her head. “I mean, it is that. Like, wow, that’s a lot to unpack. But the men at the dinner. They’re from Lunar Asset Management.”

“Okay?”

“It’s not okay!” Gods, why wasn’t anyone else capable of seeing what a problem this was? Ramble said they had seen the property tax filings; they said so, so why couldn’t they put this together? “That man works for them!”

“What man?”

“The one at the assessor’s office!” She threw her arms wide, panting in panic. “I saw him at the camp with Avery’s father. They went to lunch, and the signatures matched, but they didn’t, and he was there. Today. Filing more paperwork, and he saw me and he asked how long the drive was to get to Elkwater. Don’t you understand? He works for Lunar Asset. He smelled like lavender and wintergreen, and he’s in the camp with Avery and Mac!” Ramble chewed their lower lip, watching Cricket pace. “The scent was the same. It was on the papers and on him. I smelled it that night. Ramble. Please, we need to go.”

“What ni—” Ramble stopped themself, shaking the thought away. Their ears twitched, only the tips visible under their hair. “I’m sorry.”

“Ramble…”

“Crick, I want to believe you. I want to help you, but I have to put Mac and the camp over whatever you think is going on.”

“Ramble, please.”

“It’s my home, Crick. We have worked too hard for this. One day, you might understand, but what we are trying to build, what Mac is achieving, is setting the tone for broader integration. I cannot put my wife’s goals at risk because some businessman with bad cologne smiled at you.”

“Right.” Cricket straightened, rolling her shoulders back. A cold calm washed over her as she raised her face to the setting sun, little more than a sliver of gold crowning Bald Knob to the west. Ramble wouldn’t help. Her family wouldn’t help. No matter how many times she begged and pleaded, no matter how much evidence she presented, she would always be the faun who cried wolf. Never the faun who was trying to save them, which meant she was on her own. The steadiness of her realization was better than any bandage or balm and without a further word, she walked into the woods.

“Cricket,” Ramble called after her. “Where are you going?”

She didn’t answer. What good would words do? Her cousin had seen the papers, had seen the signatures with their own eyes, and was resigned to stay away. They were resigned to … they were resigned. And why shouldn’t they be? Ramble had found a home outside of Green Bank. They had found a partner who would save them if the worst happened, and what did Cricket have?

Nothing. No one. Her home was being taken from her, the thinnest sliver of hope was in trouble, and no one was coming to save her. No one was coming to save Avery.

So Cricket would save them herself.

“Cricket!” Ramble’s voice was thin through the trees, a faint echo that barely reached her ears. She balanced against a boulder to stretch out her uninjured leg, then rolled the ankle on her injured leg, wincing at the lingering tightness. Though she wasn’t fully healed, whatever latent magic the faun had kept in their fall had healed the wound enough, and Avery needed help.

The Georgia Man had been so confident, so sure that Green Bank wouldn’t be a problem. So certain the holdouts would fall in line. Cricket wasn’t smart enough to puzzle through the what, exactly, but she was clever enough to have ideas.

Rumors of a monster in the woods. The monster that had chased Cricket lingering at the camp, chasing Avery and destroying her cabin. Her signatures on the papers and that lavender and wintergreen scent clinging to the Georgia Man. Whatever he was going to do, it was happening tonight.

“Cricket, for the Gods’ sake,” Ramble cursed, their voice closer. Cricket glanced back, spotting their silhouette through the darkened trees, and she shouldered into a run. The first hoof-fall on her injured leg warbled up her thigh, her ankle protesting and hoof pinching. On a good day, on two good hooves, it would only take her an hour and a half to run the ridges between Green Bank and Elkwater. Two, if she kept to the well-trod deer trail; three, if she attempted the run in poor weather.

But injured, exhausted, and wound tighter than a banjo string? The weather might be clear, but the best Cricket could hope for was three.

The dinner would have just started and the Georgia Man wouldn’t attempt anything in daylight. All of the attacks had occurred at night when the camp was quiet, and the moon high overhead.

That’s not true.

She tripped over a root at the thought, hissing and spitting.

Because it wasn’t true. The monster had chased her at night during a storm and then again a few hours after dawn. She vividly recalled the pale orb of the moon, just visible in the sky as she cowered in a thorn bush.

She gritted her teeth and clenched her fists, fear driving her up a small hill and over a creek. All she had was the hope that the monster, the Georgia Man, would wait until full dark—until after dinner. But what if he didn’t?

What if she was already too late?

Fear pushed her on, adrenaline the only barrier between Cricket and the ache in her hoof as she chased the sunset over a lesser ridge, down into a ravine, and up again. Summiting Bald Knob and heading north along the ridge as the last of the day was swallowed by the trees and rolling hills.

The descent to Shavers Fork was harder than the climb. Full dark swallowed the Monongahela the moment the sun was out of sight, and she stumbled, her eyes unused to the deep, impenetrable black. Her ankle throbbed with every step, and her hoof felt as though someone had driven an iron spike into the pads, but she pressed on, following the creek at a pace no human could match.

The moon rose at her back, casting the woods in sultry blue light. As if on cue, an eager howl shattered the night.

Cricket grabbed the narrow trunk of a tree, jerking to a halt, her ears pricked, and every hair along her neck raised. She knew that howl, and she knew the terror of hearing it close at her back. She knew it over the sound of wild thunder and over ridgelines, and to hear it now meant only one thing: the monster had begun his hunt, and Cricket was too late.

Fullepub

Fullepub